Andrew McGregor

Terrorism Monitor 24(1)

Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC

January 15, 2026

Executive Summary:

- The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) captured al-Fashir in late October after an 18-month siege, consolidating RSF control over western Sudan and providing a potential capital for a new state.

- After entering al-Fashir, the RSF carried out mass looting, ethnic targeting, and killed 460 people at the al-Saudi maternity hospital in an attack that brought international outrage.

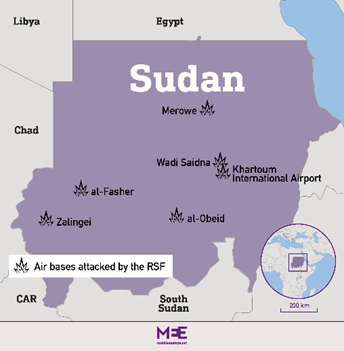

- Parallel RSF sieges in Kordofan indicate a strategy to divide Sudan. The Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) is struggling to maintain control, but still currently favors a military solution over diplomatic negotiations.

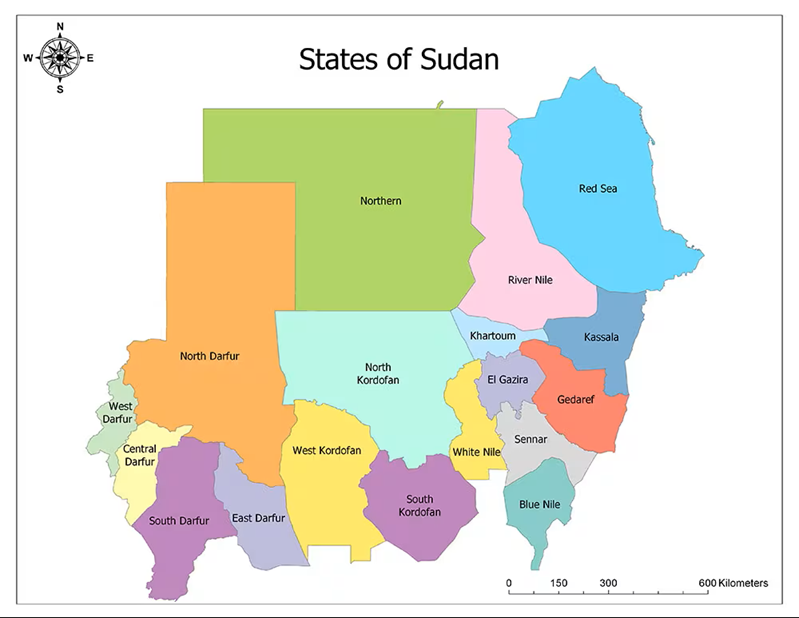

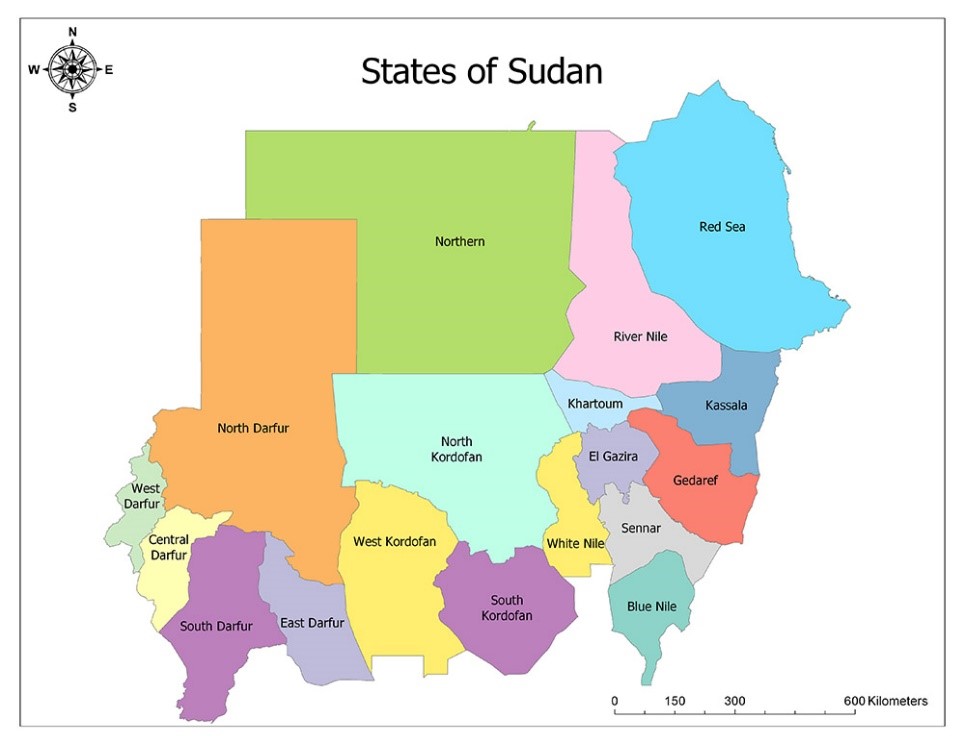

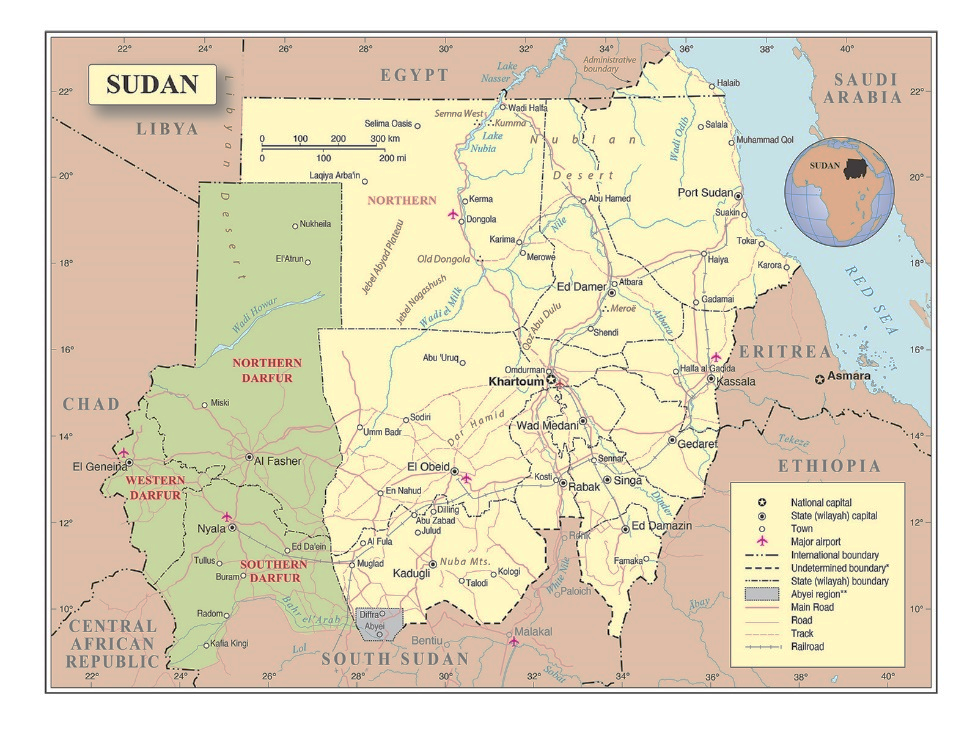

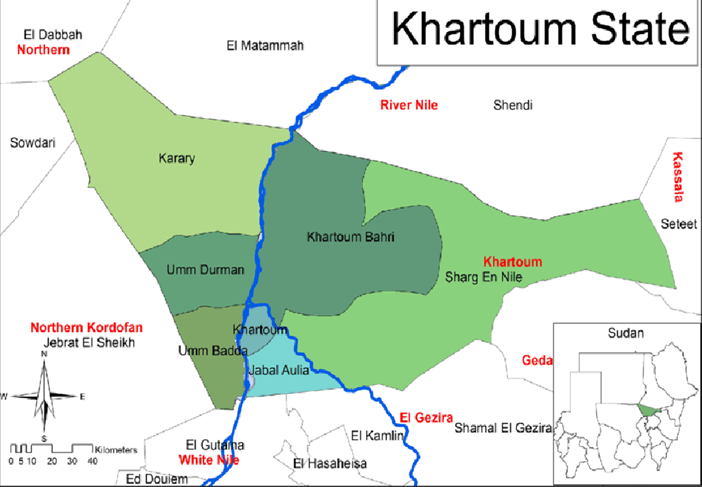

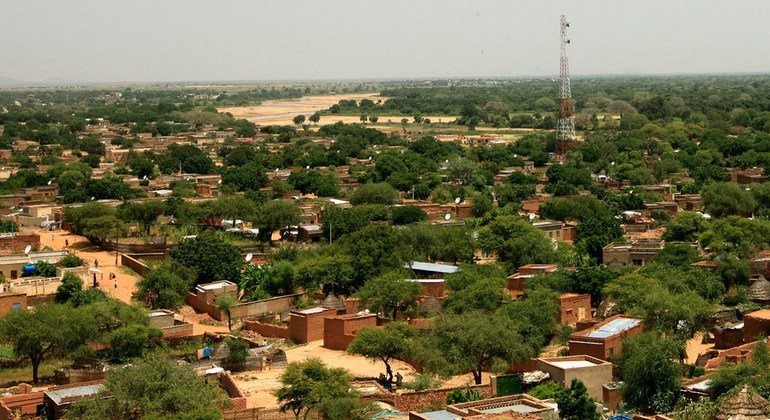

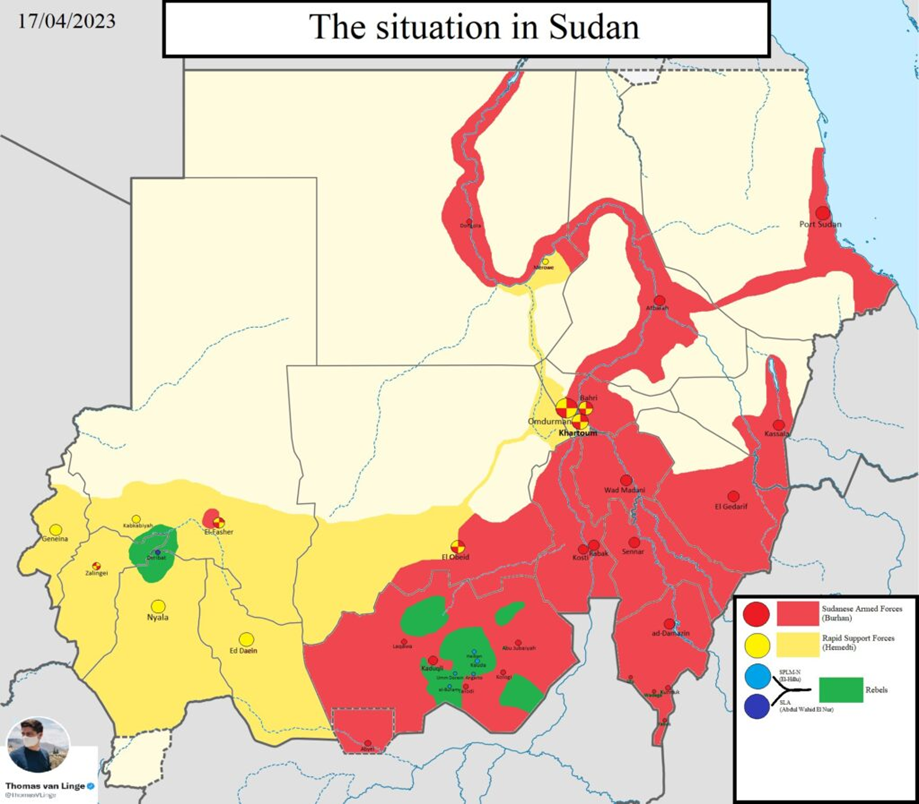

The capture of Khartoum by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in the first months of its struggle with the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) was possibly the most shocking moment of the ongoing civil war in Sudan. While the RSF has since been driven out of the capital, the RSF’s 18-month siege and capture of al-Fashir in late October is likely to have a greater long-term impact. The collapse of resistance in the North Darfur capital consolidates the paramilitary group’s hold over its power base in western Sudan while providing a potential capital for the new state the RSF and its commander Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti” aim to create.

The capture of Khartoum by the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in the first months of its struggle with the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) was possibly the most shocking moment of the ongoing civil war in Sudan. While the RSF has since been driven out of the capital, the RSF’s 18-month siege and capture of al-Fashir in late October is likely to have a greater long-term impact. The collapse of resistance in the North Darfur capital consolidates the paramilitary group’s hold over its power base in western Sudan while providing a potential capital for the new state the RSF and its commander Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti” aim to create.

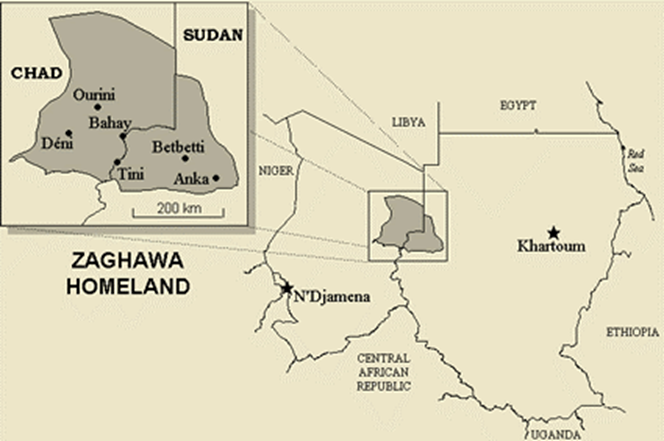

Al-Fashir’s Failed Defense

Al-Fashir was defended by the SAF’s 6th Division and its allies in the Joint Force, including former rebel movements that had signed the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement (JPA). Many were veterans of various non-Arab Darfur militias who made common cause with the former SAF enemy and the ruling Transitional Sovereignty Council (TSC) to defeat the RSF, which succeeded the notorious Arab-supremacist Janjaweed. These militias include elements of two large majority-Zaghawa groups: the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), led by Finance Minister Jibril Ibrahim; and the Sudanese Liberation Army–Minni Minawi (SLA-MM), led by Darfur governor Minni Arko Minawi (see Militant Leadership Monitor, December 7, 2017). Smaller groups include the Gathering of Sudan Liberation Forces (GSLF) under Brigadier General Mubarak Bakhit and the Sudanese Liberation Movement–Tambour (SLM-Tambour) led by Mustafa Nasr al-Din Tambour, governor of central Darfur and target of repeated RSF assassination attempts.

Conflict between the western Arabs of the RSF and previously neutral JPA signatories began on April 13, 2024, after months of tensions between the armed groups, the final straw being a massive cattle raid by Zaghawa gunmen (Ayin Network, April 19, 2024). JEM, the SLA-MM, and part of the GSLF joined the SAF coalition just as the RSF began their siege of al-Fashir.

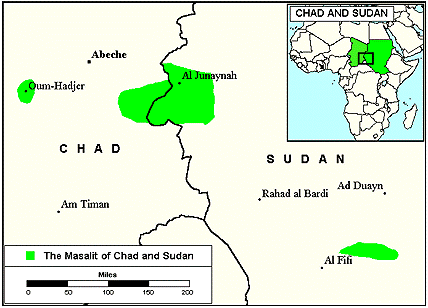

The RSF weakened resistance in al-Fashir with a siege that gradually starved the city’s 260,000 residents and the 6th Division garrison. Artillery and drones assaulted the city daily, and a roughly 45-mile sand berm was constructed to prevent escape except through narrow corridors where RSF personnel subjected those in flight to murder, robbery, and rape (Radio Dabanga, September 30, 2025). The city’s non-Arab residents were well aware of the atrocities that befell the Masalit ethnic group after the RSF seized the West Darfur city of Geneina in June 2023 (Terrorism Monitor, June 26, 2023). The RSF targeted the overcrowded refugee camps around al-Fashir, and the main place of refuge became the town of Tawila, 43 miles away and controlled by the Fur militia, SLA-‘Abd al-Wahid (SLA-AW).

Only days before the fall of the city, Darfur governor Minni Minawi claimed the RSF was using South Sudanese mercenaries in its assaults, having “exhausted its fighters” (Sudan Tribune, October 23, 2025). Colombian mercenaries supported by the UAE are also believed to have taken part in the RSF siege, operating drones and heavy weapons (Ayin Network, October 10, 2025). By October 21, only a third of al-Fashir’s 600,000 people remained, trapped in a city without food or medical supplies and where most water sources had been destroyed by shelling (Ayin Network, October 21, 2025).

On October 25, the RSF launched attacks from several directions on the SAF’s 6th Division headquarters. Tanks and drones drove off the initial attacks. The RSF resumed the assaults the next morning at dawn, however, with drones and ground units forcing their way through the base’s main gate. The RSF seized large quantities of military supplies and reported destroying “huge military vehicles” (Radio Tamazuj, October 26, 2025). Thousands of SAF troops and their allies withdrew to a strong-point at Daraja, northwest of al-Fashir, leaving behind many comrades taken prisoner or trapped inside the city by RSF fighters (Ayin Network, October 26, 2025).

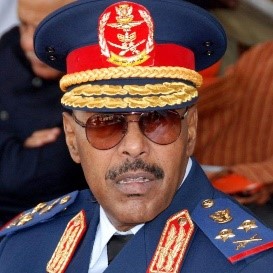

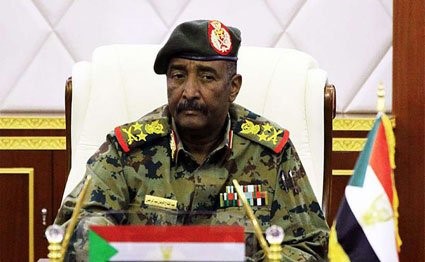

Later on October 26, the RSF announced that its forces had “broken the backbone of the army and allied armed movements, inflicting heavy casualties on them, destroying massive military vehicles, and seizing all military equipment” (Ayin Network, October 26, 2025). A video of RSF fighters celebrating the capture of the 6th Division’s base in al-Fashir was posted to social media (X/@SudanTribune_EN, October 26, 2025). According to SAF commander General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, the military command in al-Fashir “decided to withdraw due to the systematic destruction and killing of civilians” (Radio Dabanga, October 28, 2025).

Prior to the final assault on al-Fashir, ‘Abd al-Rahim Daglo, Hemetti’s brother and second-in-command, was filmed telling RSF fighters: “I declare it here … I don’t need any prisoners at all” (X/@Sudan_tweet, October 30, 2025). The entry of the RSF was marked by looting, arson, gang-rapes, the targeting of non-Arab ethnic groups for slaughter, and the summary execution of prisoners and those suspected of supporting the SAF and its affiliates (Radio Tamazuj, November 1, 2025).

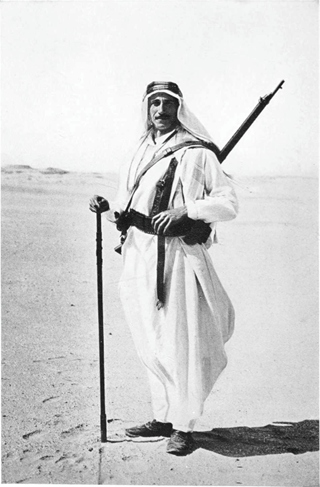

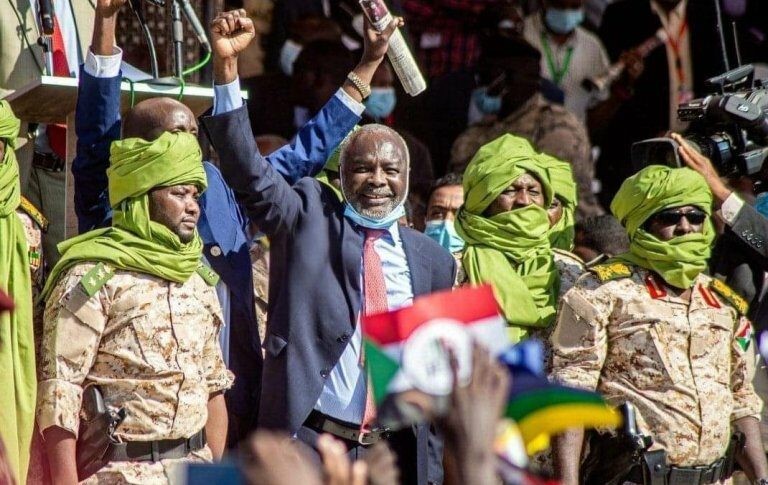

Fatah ‘Abd Allah Idris “Abu Lulu” (Ayin Network)

Fatah ‘Abd Allah Idris “Abu Lulu” (Ayin Network)

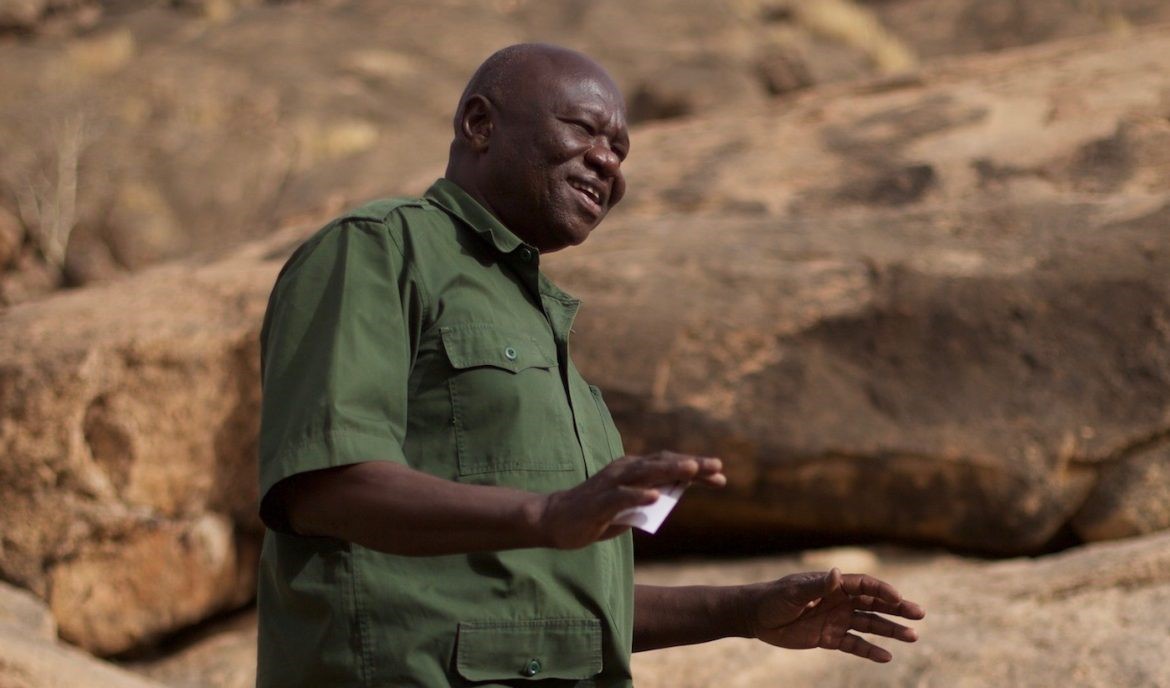

In the most appalling incident, incoming RSF fighters killed 460 patients, healthcare workers, and families at al-Saudi maternity hospital (Radio Tamazuj, October 29, 2025). Fighting continued in the western part of the city even after the RSF began house-to-house “combing operations” throughout the rest of al-Fashir. Besides the Saudi maternity hospital, gunmen targeted aid workers and anyone found in the university or Interior Ministry buildings. In addition, an ordinary soldier in the RSF, Fatah ‘Abd Allah Idris “Abu Lulu” discovered a murderous calling during the occupation, joyfully slaughtering civilians attempting to leave the city even as they begged for their lives. After social media videos of his activities attracted international attention, the RSF claimed to have arrested him and denied he was a formal member of the group (Ayin Network, November 10, 2025).

Hemetti’s Response

Hemetti deflected international condemnation of the atrocities, insisting that they were the work of individuals who would be investigated by an RSF committee and held responsible (Ayin Network, November 10, 2025). The atrocities captured the attention of the International Criminal Court (ICC), however, which is monitoring for evidence of war crimes (Radio Dabanga, November 3, 2025).

Sixth Division and Joint Force survivors, meanwhile, have attempted to regroup in the Wana Mountains (or Hills), northwest of al-Fashir. Without provisions, they will be forced to either regain territory formerly held by the SAF, surrender to the RSF, or attempt an escape to an uncertain welcome in Chad.

The storming of al-Fashir has been accompanied by simultaneous sieges of cities in neighboring Kordofan, part of the RSF’s strategy to form a western Sudanese state. The strategic city of Bara in North Kordofan fell to three waves of RSF attackers on October 25, followed by the now-typical door-to-door slaughter of its non-Arab civilian population and all those considered sympathetic to the SAF. The operation helps the RSF complete its encirclement of the North Kordofan capital, al-‘Ubayd (Mada Masr, October 27; Ayin Network, November 7, 2025).

In neighboring South Kordofan, the RSF has intensified its sieges of the cities of Kadugli and Dilling with the targeting of civilian homes by drones. The largely Nuba troops of the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army-North (SPLA-N), led by ‘Abd al-Aziz al-Hilu, have joined the RSF in these sieges (see Militant Leadership Monitor, July 31, 2011). The capture of Kadugli, in particular, would aid the RSF effort to consolidate its control of western Sudan (Ayin Network, November 6, 2025).

Conclusion

The SAF is struggling to hold parts of Kordofan that it still controls and, at present, cannot muster the strength to push back the RSF, making a division of the country possible. For now, however, the SAF is still seeking a military rather than a diplomatic solution. Pressure to retake western Sudan coming from Darfur-origin Joint Forces allies who are now stranded in central and eastern Sudan will play an important part in the SAF’s near-term operational decisions.