Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report, October 15, 2017

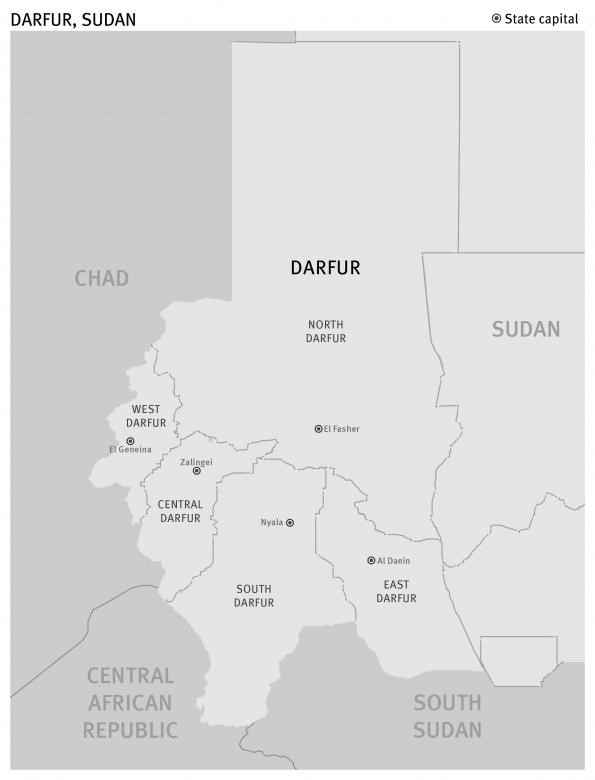

Ten thousand members of Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF – al-Quwat al-Da’m al-Sari) have been transferred from Kordofan to North Darfur to help implement a mandatory disarmament campaign in the region. Almost exclusively Arab in composition, the RSF will attempt to disarm not only non-Arab rebel forces still in the field, but also Arab elements of the government’s Border Guard Force (BGF) that are in near rebellion and nomadic tribesmen who rely on their weapons to protect their herds from thieves and predators.

Sudan Armed Forces Armor in Darfur (Nuba Reports)

Sudan Armed Forces Armor in Darfur (Nuba Reports)

Both the RSF and the BGF are products of Khartoum’s efforts to make the infamous and internationally reviled “Janjaweed” disappear. Absorbing these ill-disciplined Arab militias into better defined government formations helped support a government narrative that the Janjaweed were not government-backed marauders, but rather unaffiliated bandits that had been removed from Darfur through the efforts of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF). In theory, transforming these militias into salaried employees of the state would bring them under tighter state control at a time when many Janjaweed and their commanders were beginning to have second thoughts about having sacrificed their reputation in return for empty promises from Khartoum. In practice, the RSF has transformed itself into a border control force reducing migration flows to Europe with ample funding from the European Union, while the BGF has evolved into a new formation, the Sudanese Revolutionary Awakening (“Sahwa”) Council (SRAC), which has slipped from government control with the help of enormous profits from its domination of artisanal gold mining in northwestern Darfur.

Both RSF and BGF are composed of members of the semi-nomadic Abbala (camel-raising) tribes of northern Darfur, the main source of Janjaweed manpower after the ongoing Darfur rebellion began in 2003. Some of the Abbala tribes, including the northern Rizayqat, had not been allotted specific lands for their use by the old Fur Sultanate (c. 1600-1916) or the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium administration (1916-1956).

While customary arrangements between the semi-nomadic Arabs and sedentary non-Arab groups regarding land-use and migration routes continued into the independence period, these accommodations began to fall apart in the 1980s as drought and an encroaching desert placed new pressures on traditional systems. Possessing useful pastures became essential for the pastoralist Arabs, but after centuries of land allotments by Fur Sultans (the feudal hakura system) and their colonial successors, there was no unclaimed land to be had; dispossessing others was the only means of establishing a new dar, or tribal homeland.

The Baqqara (cattle-raising) Arabs of southern Darfur, whose dar-s were legally and traditionally defined, had little involvement with the depredations of the Janjaweed. Unfortunately for the Baqqara, this distinction is little understood outside of Sudan. It is also important to note that not all the Abbala tribes were involved with the Janjaweed; the Janjaweed was primarily drawn from sections of the northern Rizayqat (who were much affected by lack of land-title) and elements of Arab groups from Chad and Niger who had migrated to Darfur with the encouragement of the Khartoum regime, which suggested they carve out their own land-holdings from territory belonging to non-Arab tribes the regime viewed as supporters of the rebellion.

The progress of Khartoum’s disarmament campaign will have important consequences for the future of the Darfur rebellion, the regime’s continuing efforts to centralize power in Sudan and even the European Union’s campaign to reduce illegal migration into Europe.

Musa Hilal: From Janjaweed to Border Guard

With the possible exception of Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for war crimes in Darfur, no individual is more closely associated with the deeds of the Janjaweed than Shaykh Musa Hilal Abdalla, a member of the Um Jalul clan of the Mahamid Arabs.

Sudan President Omar al-Bashir (center) with Musa Hilal (right of of al-Bashir) (al-Jazeera)

Sudan President Omar al-Bashir (center) with Musa Hilal (right of of al-Bashir) (al-Jazeera)

Hilal is the nazir (chief) of the Mahamid, a branch of the northern Rizayqat tribal group (the northern Rizayqat includes the Mahamid, Mahariya, and Ireiqat groups. The southern Rizayqat are baqqara with little involvement in the Janjaweed). From his home village of Misteriya, Hilal became involved in the 1990s with the Arab Gathering (Tajamu al-Arabi), an Arab supremacist group following an ideology developed by Mu’ammar Qaddafi and the leaders of Libya’s Islamic Legion (Failaq al-Islamiya) in the 1980s. The Um Jalul began to clash with non-Arab Fur and Zaghawa tribesmen in the 1990s, leading to Hilal’s eventual arrest and imprisonment in Port Sudan in 2002 on charges of inciting ethnic violence.

Hilal’s prison term was brought to an abrupt end by the shocking April 2003 raid on Darfur’s al-Fashir military airbase by Fur and Zaghawa rebels retaliating against growing waves of government backed Arab violence against non-Arab communities. An unnerved government realized the SAF might not be capable of containing the mobile hit-and-run tactics of the rebels developed during fighting in Chad in the 1980s. After deciding to turn to local tribal militias to carry the counterinsurgency campaign, suddenly Shaykh Musa was just what the regime needed. Consequently, Hilal was released in June 2003 to organize a counterinsurgent force infused with pro-Arab ideology and armed, supplied and directed by SAF intelligence units. This was the “Janjaweed.” [1]

The strategy employed to hobble the militarily powerful insurgent forces was to cripple their support base and supply system through the destruction of defenseless Fur and Zaghawa villages. Tactics typically involved an initial bombardment by the Sudanese Air Force (usually crude “barrel-bombs” rolled out from Russian-built Antonov transport aircraft), followed by waves of horse and camel-borne Janjaweed and a final “mopping-up” force of Sudanese regulars and intelligence agents. Murder, torture, rape and looting were all part of a process intended to punish relatives of insurgents and even those with no connection to the rebels other than a shared ethnic or tribal background. Incitement of ethnic hatred, promises of immunity and a license to loot freely helped give free rein to the basest instincts of the Janjaweed; those reluctant to join in such activities were subject to imprisonment and the collective punishment of their families.

One of Hilal’s leading lieutenants during the 2003-2005 period of the worst Janjaweed abuses was Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti,” from the Awlad Mansur clan of the Mahariya branch of the northern Rizayqat, though by this time the Awlad Mansur were resident in South Darfur, having moved there in the 1980s where they seized Fur lands in the southern Jabal Marra region.

Hilal’s notoriety brought largely meaningless sanctions from the UN Security Council in April 2006. Instead of ostracism, Hilal was brought to Khartoum, where he was integrated into the government as a special advisor to the Ministry of Federal Affairs and a member of parliament in the ruling National Congress Party (Hilal later repudiated his membership in the NCP).

By 2005 the government’s campaign in Darfur had begun to attract unwanted international attention, including ill-informed but nonetheless damaging accusations of “genocide” from various media sources and celebrity activists. However useful to the regime, the “Janjaweed” had to go. The solution was integration into the Border Guards, previously a small and little known camel-mounted unit. Arab tribesmen serving in the Janjaweed for loot were now given salaries and government ID cards which helped shield the new Border Guards from prosecution for war crimes while bringing them under tighter regime control. Musa Hilal was made a top commander in the expanded BGF.

The Return of Musa Hilal

Following a dispute with the government, Musa Hilal returned to northwest Darfur in January 2014, where, despite remaining commander of the BFG, he established the 8,000 strong Sudanese Revolutionary Awakening (Sahwa) Council (SRAC) as a vehicle for his personal and tribal political agenda. By March 2014 he had brought the northwestern Darfur districts of, Kutum, Kebkabiya, al-Waha and Saraf Omra under SRAC’s administrative control by the exclusion of government forces. Clashes between Hilal’s mostly Mahamid followers and government security forces began to occur with regularity.

Musa Hilal’s SRAC is also involved in a struggle with the RSF over control of Jabal Amer (northwest of Kabkabiya), where gold was discovered in 2012. The SAF withdrew from the area in 2013 under pressure from Hilal’s forces, which then defeated the rival Bani Hussein Arabs in a bloody struggle for control of the region. In 2016, the UN Panel of Experts on Sudan reported that Hilal was making approximately $54 million per year from SRAC’s control of the artisanal gold mining at Jabal Amer, though the report was not publicly released due to Russian objections. Gold is now the largest source of revenue in Sudan since South Sudan and its oil fields separated in 2011, though much of it is smuggled out of the country to markets in the Gulf States (Radio Tamazuj, April 27, 2016; Radio Dabanga, April 5, 2016).

In May 2017, SRAC spokesman Ahmad Muhammad Abakr called for “all Arab tribes in Darfur, Kordofan, and Blue Nile state to disobey the government’s military orders and refrain from participating in its war convoys.” Suggesting their cause had been “stolen by the government,” Abakr declared:

The ongoing wars are now fabricated for the purpose of a divide-and-rule policy of which the ruling elite in Khartoum is the ultimate beneficiary rather than the people of Sudan… If there is a need for war, we ask you to point weapons against those who employ you to fight on their behalf in order to take your political, economic and military rights instead of fighting a proxy war (Radio Dabanga, May 31, 2017).

The Rapid Support Forces

Prior to Hilal’s return to Darfur, Khartoum had detached the BGF’s Fut-8 Battalion (based in Nyala, South Darfur and commanded by Muhammad Hamdan Daglo) from the rest of the force and used it as the core of a new paramilitary, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The move was partly a response to internal tensions in the BGF between Fut-8 and the Hilal-commanded Fut-7 Battalion, which claimed Fut-8 was favored by Khartoum in terms of supplies of weaponry, vehicles and supplies. [2] At the same time, Daglo and his followers complained that Hilal was not distributing BGF resources fairly, especially the all-important Land Cruisers. [3]

The RSF came under the direct authority of the National Security and Intelligence Service (NISS – Jihaz al-Amn al-Watani wa’l-Mukhabarat) and continues to enjoy the patronage of Second Vice President Hassabo Muhammad Abd al-Rahman, a Rizayqat. [4]

The RSF was integrated into the SAF in 2016, but with an unusual semi-autonomous status under the direct command of President Bashir (a Nile Valley or “riverine” Ja’alin Arab). Saying that the establishment of the RSF was the best decision he had ever made as president, Bashir recently told a graduating group of 1450 RSF recruits in Khartoum that their aim must be to “show force and terrorize the enemies” (Sudan Tribune, May 14, 2017).

Despite government claims that Darfur was stabilized, the RSF took a leading role in May 2017 alongside the SAF in a bitter four day battle around Ayn Siro in the Kutum district of North Darfur last May against the Zaghawa-led Sudan Liberation Movement – Minni Minawi (SLM-MM) and the allied Sudan Liberation Movement/Army – Transitional Council (SLM/A-TC), led by Nimr Abd al-Rahman. [5]

Several leading prisoners, including veteran rebel Muhammad Abd al-Salim “Tarada,” military commander of the Sudan Liberation Movement – Abd al-Wahid (SLM-AW) until June 2014 and then a commander in the SLM/A-TC, were reported to have been killed by NISS agents following their capture. The defeated rebels fled westward along the Upper Wadi Howar into Chad, though they later issued a joint communiqué making an unlikely claim to have driven off the government forces. The heavy losses suffered by the SLM/A-MM marked a disappointing return to Darfur after the movement had spent nearly two years fighting as mercenaries in Libya (Sudan Tribune, May 29, 2017; May 23, 2017; Sudan Vision, May 22, 2017; Radio Dabanga, May 23, 2017; IRIN, August 2, 2017).

RSF Commander Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti”

RSF Commander Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti”

RSF commander Daglo claimed the Darfur rebels were aided at Ayn Siro and Wadi Howar by Chadian opposition fighters (who have also been fighting as mercenaries in Libya) [6] and insinuated that the Chadians were harbored and supported logistically by Musa Hilal, though he did not elaborate on the reasons for this new support by Hilal for Darfur’s non-Arab rebels (Sudan Tribune, June 4, 2017).

By January 8, 2017, the RSF announced the capture of over 1500 illegal migrants in the last seven months following the interception of 115 migrants several days earlier (Sudan Tribune, January 9, 2017). RSF activity along the Libyan border is intended to intercept traffickers in humans and narcotics and to demonstrate Sudan’s commitment to reducing flows of illegal migrants after the European Union made a grant to Sudan of €100 million to deal with the issue.

Most of the illegal migrants making their way through Sudan to Libya and on into Europe hail from Eritrea, Ethiopia and Yemen. The EU is funding the construction of two RSF camps equipped with modern surveillance equipment and electronics for intercepting and detaining illegal migrants. [7]

Rejecting Integration

Defence Minister Lieutenant General Ahmad Awad Bin Auf announced a reorganization of the SAF’s “supporting forces” on July 19, 2017. A central part of the reorganization was the planned integration of the BGF into the RSF. Within days, SRAC spokesman Haroun Medeikher announced the BGF would refuse to allow its integration, saying the decision was “ill-considered and unwise” and had been taken without consulting the BGF leadership (Radio Dabanga, July 23, 2017).

On news of the refusal, one of Hilal’s old opponents, Abd al-Wahid al-Nur (leader of the largely Fur SLM-AW), used radio to reach out to the Arab militia leader, stating that while Musa Hilal’s “awakening conscience may be belated,” it was “time for all the Sudanese people to stand united against the regime” (Radio Afia Darfur, via Sudan Tribune, August 20, 2017). Abd al-Wahid has always been the rebel commander most likely to seek terms with Darfur’s Arab community, recognizing the symbiotic relationship between pastoralists and farmers as well as the existence of a common enemy in the Khartoum regime.

Hilal has also stepped up his anti-government rhetoric, urging his tribesmen not to volunteer for the SAF’s campaign in Yemen, claiming Vice-President Abd al-Rahman and General Daglo have stolen millions of dollars given to Sudan by Saudi Arabia and the UAE in return for their participation in the intervention against the Zaydi Shiite Houthis in Yemen’s ongoing civil war (al-Jazeera, September 10, 2017).

Turmoil on the Libyan Border

On September 22, 2017 the RSF claimed to have killed 17 human traffickers a day earlier with a loss of two RSF men. The encounter took place in the Jabal ‘Uwaynat region where the Sudanese, Libyan and Egyptian borders meet. [8] An RSF field commander, Lieutenant Colonel Hassan Abdallah, described the intercepted group as “the largest armed gang operating in human trafficking and illegal immigration” on the Libyan-Sudanese border. The RSF also claimed to have detained 48 illegal migrants being shipped to Libya (Radio Dabanga, September 24, 2017).

A SRAC spokesman insisted those killed were SRAC members involved in trading but not trafficking, adding that the men had initially only been detained by the RSF, but were killed after three days of negotiations failed to reach an agreement on a ransom (Radio Dabanga, September 25, 2017). One of those killed was a Hilal bodyguard, Sulayman Daoud. Leading SRAC member Ali Majok al-Momin counter-charged the RSF with “trading and smuggling vehicles over the borders with Chad and Libya” (Radio Dabanga, September 25, 2017).

The incident was not the first involving the RSF and SRAC on the Libyan border. Seven SRAC members, including leading member Omar Saga and Muhammad al-Rayes, another of Musa Hilal’s bodyguards, were arrested near the border by the RSF on their return from Libya on August 11, 2017.

Behind the RSF’s vigilance against Hilal supporters on the Libyan border is Khartoum’s fear that Hilal is establishing cross-border contacts with “Field Marshal” Khalifa Haftar, leader of the Libyan National Army (LNA – actually a strong coalition of militias under Haftar’s command that oppose the internationally recognized Libyan government in Tripoli). Hilal also has important ties to militarily powerful Chad, whose president, Idriss Déby Itno (a Zaghawa), is Hilal’s son-in-law. Further complicating matters for the government is the high probability that many Mahamid and other Arab members of the RSF could defect to the BGF in the event of a full-scale conflict between the two.

Musa Hilal reportedly sent 200 vehicles full of armed fighters to besiege the RSF camp until those RSF members involved in the September 22 killings were turned over to the BGF (Sudan Tribune, September 26, 2017). A battle between the BGF and the RSF was averted when the two sides agreed to third-party mediation. The process favored the BGF, with the RSF making concessions over control of the gold workings at Jabal Amer and handing over vehicles, military equipment and BGF members detained in the attack (Radio Dabanga, September 29, 2017).

SRAC claimed on October 7, 2017 that two columns of armed RSF Land Cruisers, one from Ayn Siro and one from Kabkabiya, had been sent to “punish Hilal” by defeating his forces and bringing him in to Khartoum “dead or alive” (Radio Dabanga, October 9, 2017; Sudan Tribune, October 8, 2017). The accusation was not new; Shaykh Musa has claimed for years that Khartoum is intent on his assassination.

Conclusion

According to SRAC spokesman Haroun Medeikhir, Musa Hilal met in August with BGF commanders and traditional leaders across Darfur to discuss what he termed Khartoum’s attempt to “dismantle the Arab tribes” (Sudan Tribune, August 14, 2017). Key to bringing the Arab tribes to heel would be disarmament. It was no surprise then that the tribes were alarmed when Vice-President Abd al-Rahman announced a new six-month campaign to disarm Darfur’s militias beginning on October 15.

The SAF and RSF are also taking over 11 military bases being abandoned by the United Nations/African Union Mission in Darfur (UNAMID). [9] The world’s second-largest peacekeeping force is in the first phase of a withdrawal prompted largely by international exhaustion with the complex Darfur issue and UNAMID’s annual budget of $1.35 billion. Khartoum, which never wanted the mission in the first place, began to push for an early UNAMID exit after the mission called for an investigation of the mass rape of 221 women and underage girls by SAF troops in the Fur village of Tabit in October 2014. [10] Khartoum maintains that Darfur has been stabilized and rebel fighters either expelled or neutralized.

Khartoum’s new effort to consolidate its power in Darfur raises renewed possibilities of an alliance of Arabs and non-Arabs against Khartoum, but the events of the last three decades have left a massive and deeply ingrained distrust between the two. Arab and non-Arab rebel groups in Darfur have toyed with the idea of an alliance against the center since 2007, when some Arab factions began to realize their international reputation had been irreversibly stained from manipulation by an insincere Khartoum regime that never had their interests in mind. [11] In addition, the services and development programs promised to the Arabs for their participation in the Janjaweed campaigns never materialized, leaving the Darfur Arabs no better off than they had been in 2003. Tension between the Darfur Arabs and the riverine Arab groups that control the government (the Ja’ailin, the Danagla and the Sha’iqiya) tend to bring out the strong prejudices that exist between the two Arab groups. The riverine Arabs regard the Darfur Abbala and Baqqara as backwards and “Africanized.” The Darfur Arabs, however, claim descent from the great Juhayna tribe of Arabia; some extremists seeking to shed the control of the riverine Arabs have described the latter as “half-caste Nubians.” [12]

Even Musa Hilal has at times demonstrated a broader understanding of Darfur’s ethnic make-up and the methods used by Khartoum to create and exploit racial and ethnic divisions. In 2008, Hilal told a gathering of Baqqara and Abbala tribal leaders that all Darfuris were “Africans” of mixed Arab and African origin who needed to work on restoring their traditionally cooperative social fabric. [13] In a private meeting with U.S. diplomats that followed, Hilal said “We found out that we have more in common with the Africans of Darfur than with these Nile Valley Arabs,” and even made a surprising recantation of the Arab supremacist philosophy he had followed for decades, suggesting that, based on their better education and moderation, “the Fur should lead” in Darfur, a return to the leadership structure of the old Fur Sultanate. [14]

Complete faith in Daglo’s loyalty does not exist in Khartoum, where conciliation is common when it is in the regime’s interests but indiscretions are never completely forgotten. In this case the issue is Daglo’s mutiny against the government in 2007 over RSF salaries, land and a dispute with Musa Hilal. Unable to assert its authority in Darfur and unwilling to see large numbers of armed Arabs join the rebels, the regime was forced to make major concessions to keep Daglo’s forces onside. When the salaries still went unpaid, Daglo threatened to storm Nyala, the capital of South Darfur. Money and arms eventually brought an end to the mutiny, but not the suspicion. [15]

While some Arabs and non-Arabs may discover they have a common enemy in Khartoum, they are still far from having common goals. In recent years, Khartoum has shown little interest in mediating disputes between Arab groups in Darfur that leave these groups weak, preoccupied and unable to unite against the center, especially at a time when budget cuts related to the loss of oil-rich South Sudan make it difficult for the regime to buy cooperation. The consequent environment of perpetual tension and suspicion does not bode well for the success of a campaign to seize the weapons of Darfur’s armed factions by force. In making the attempt the regime will encounter the consequences of its long-standing cynicism and duplicity on the Darfur file and a divide-and-rule policy that has left it with fewer friends in the region than when the rebellion and counter-insurgency began in 2003.

NOTES

- The term “Janjaweed,” which predates the counter-insurgency, was used colloquially in reference to armed bandits. The term was not used by the Arab militias themselves or the government.

- “Border Intelligence Brigade (Al Istikhbarat al Hudud) (AKA Border Guards)” Sudan Human Security Baseline Assessment (HSBA), Small Arms Survey, Geneva, November 2010, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/facts-figures/sudan/darfur/armed-groups/saf-and-allied-forces/HSBA-Armed-Groups-Border-Guards.pdf

- Julie Flint, “Beyond ‘Janjaweed’: Understanding the Militias of Darfur,” Small Arms Survey, Geneva, 2009, fn.78, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/working-papers/HSBA-WP-17-Beyond-Janjaweed.pdf

- For the RSF, see, “Khartoum Struggles to Control its Controversial ‘Rapid Support Forces’,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor, May 30, 2014, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=852

- The SLM-MM is named for its Zaghawa commander, Minni Minawi (a.k.a. Sulayman Arcua Minawi). Like Hilal, Minawi joined the government in Khartoum from 2006 to 2010 as Senior Assistant to the President of the Sudan before returning to the rebellion in Darfur. Nimr Abd al-Rahman was captured by government forces in the battle and replaced as SLM-TC head by al-Hadi Idriss Yahya.

- See Jérôme Tubiana and Claudio Gramizzi, “Tubu Trouble: State and Statelessness in the Chad-Sudan-Libya Triangle,” Small Arms Survey, Geneva, 2017, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/working-papers/SAS-CAR-WP43-Chad-Sudan-Libya.pdf; “Rebel or Mercenary? A Profile of Chad’s General Mahamat Mahdi Ali,” Militant Leadership Monitor, September 7, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4010 .

- See Suliman Baldo, “Border Control from Hell: How the EU’s migration partnership legitimizes Sudan’s ‘militia state’,” Enough Project, April 2017, https://enoughproject.org/files/BorderControl_April2017_Enough_Finals.pdf

- For Jabal ‘Uwaynat and RSF activity in the area, see: “Jabal ‘Uwaynat: Mysterious Desert Mountain Becomes a Three-Border Security Flashpoint,” AIS Special Report, June 13, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3930

- The UNAMID bases are located at Eid al-Fursan, Tullus, Muhajiriya, al-Malha, Mellit, Um Kedada, Abu Shouk, Zamzam, al-Tine, Habila and Foro Baranga.

- “Mass Rape in North Darfur: Sudanese Army Attacks against Civilians in Tabit,” Human Rights Watch, February 11, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/02/11/mass-rape-north-darfur/sudanese-army-attacks-against-civilians-tabit

- See Andrew McGregor: “Darfur’s Arabs Taking Arms against Khartoum,” Canadian Institute of Strategic Studies Commentary (November 2007), https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=559

- Julie Flint and Alex de Waal: Darfur: A New History of a Long War, Zed Books, London, 2008.

- “Iftar with the ‘Janjaweed’,” U.S. Department of State Cable 08KHARTOUM1450_a, September 25, 2008, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08KHARTOUM1450_a.html

- Ibid.

- “Border Intelligence Brigade (Al Istikhbarat al Hudud) (AKA Border Guards)” Sudan Human Security Baseline Assessment (HSBA), Small Arms Survey, Geneva, November 2010, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/facts-figures/sudan/darfur/armed-groups/saf-and-allied-forces/HSBA-Armed-Groups-Border-Guards.pdf; Julie Flint, op cit, 2009, pp.34-36, http://www.smallarmssurveysudan.org/fileadmin/docs/working-papers/HSBA-WP-17-Beyond-Janjaweed.pdf