Andrew McGregor

Terrorism Monitor, Washington DC

June 26, 2023

Arab Tribesman and RSF vehicle, West Darfur, June 2022 (AP)

Arab Tribesman and RSF vehicle, West Darfur, June 2022 (AP)

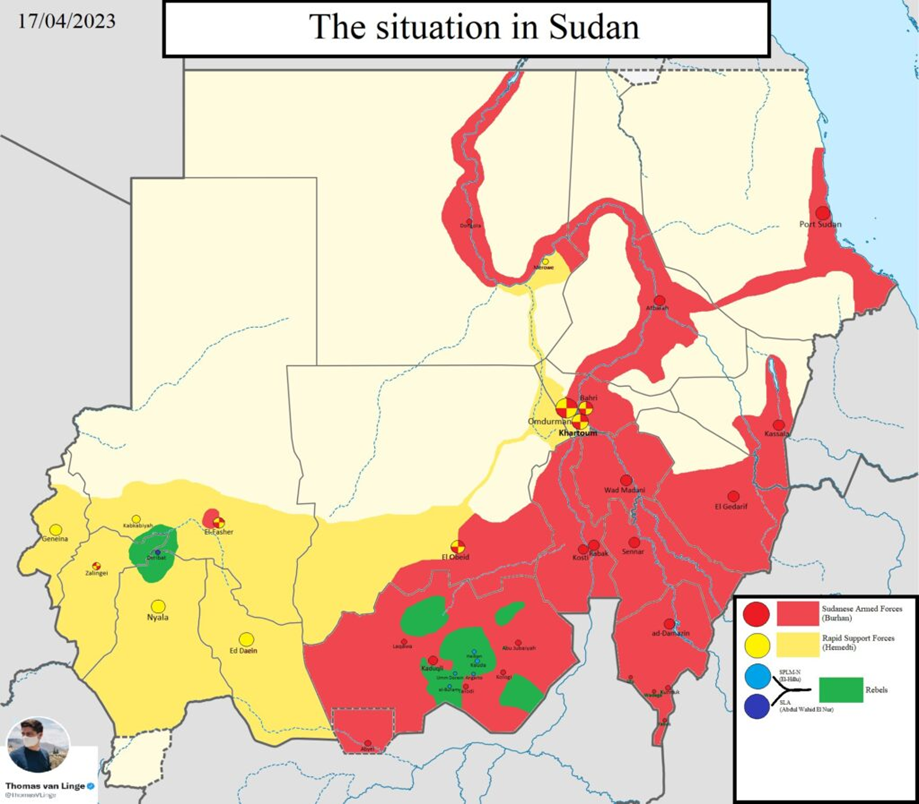

The conflict between the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) in Sudan started on April 15. However, parts of Darfur were already experiencing ethnic and political violence, much of it dating back to the 1990s. While the clashes in Khartoum dominate international media attention, fighting in the more remote Darfur region has exploded in intensity and bloodshed, particularly in one of the region’s five states—West Darfur.

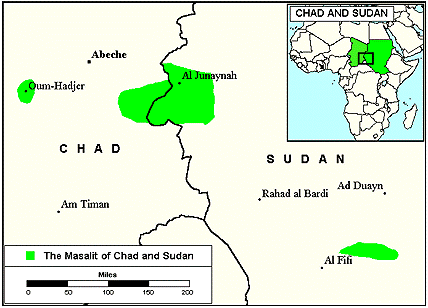

West Darfur is home to the Masalit people, Black Africans claiming ancestral origins in Tunisia. Historically, the region is known as “Dar Masalit” (dar meaning “abode of” or “home of”). Based in the historically volatile border region between western Darfur and eastern Chad, the Masalit took advantage of political upheavals in the region to establish an independent border sultanate in the late 19th century. The young sultanate, however, immediately faced invasion by Sudanese Mahdists and attacks from the Sultan of Darfur, who considered the sultanate his property.

Range of the Masalit People (Joshua Project)

Range of the Masalit People (Joshua Project)

Famed for their fierceness in battle, the Masalit also fought two major battles against the French in 1910, halting the eastward expansion of the French colonialists and the absorption of Dar Masalit into French-ruled Chad. The Anglo-Egyptian army that occupied Darfur in 1916 continued west into Dar Masalit, leading to its eventual formal absorption in 1922 into the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (and later independent Sudan) following a border treaty between Britain and France. To this day, however, the Masalit and other tribes of the region have closer relations with their kinsmen in Chad than Sudan’s ruling Nile Valley Arabs. Al-Geneina (a.k.a. al-Junaynah), the capital of West Darfur, is 745 miles from Khartoum, but only 17 miles from Chad.

In all its turbulent history, the escalating conflict in West Darfur now represents the greatest threat in many years to the existence of the Masalit homeland.

Arabism vs. Traditional Society

As the Khartoum regime began to promote an Arab supremacist/Islamist ideology in the 1990s, it replaced the traditional administrative structure of the Masalit with appointees from the military and the Rizayqat Arabs of North Darfur. Persecution of Masalit community leaders followed, and soon Arab militias began to attack Masalit villages and burn their crops to force them into out-migration. By 1997-1999, the Masalit were suffering thousands of civilian casualties as government-armed Arab militias ran wild under the direction of national intelligence units. Khartoum staunched local resistance by disarming the Masalit and conscripting their young men to fight the rebels in South Sudan.

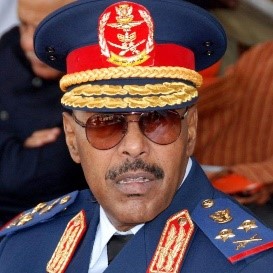

Sudan Minister of National Defense ‘Abd al-Rahim Muhammad Husayn

Sudan Minister of National Defense ‘Abd al-Rahim Muhammad Husayn

In 1999, then Sudanese Interior Minister ‘Abd al-Rahim Muhammed Husayn declared the Masalit to be outlaws and enemies of the regime, falsely claiming they had murdered all the Arab leaders in Dar Masalit. [1] Promoted to Minister of National Defense, ‘Abd al-Rahim found himself facing an International Criminal Court (ICC) arrest warrant in March 2012 for war crimes and crimes against humanity. [2] Fighting between the Masalit and Arabs broke out again in January 2020 and again in April 2021, leaving 452 dead and over 500 wounded (Darfur24, July 21, 2021).

Sudanese Army Recruitment in Darfur

More recently, the Sudanese Army launched an intensive recruitment effort in Darfur a month before hostilities between the army and the RSF, which is composed mainly of Darfur Arabs, broke out in mid-April. The recruitment campaign targeted Arab tribesmen, focusing on the Mahamid clan of the Rizayqat Arabs. The chief of the Mahamid is Musa Hilal, the former leader of the infamous Janjaweed and a main rival of his cousin and former protegé, RSF leader Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti,” a member of the Mahariya branch of the Rizayqat.

Some Arab leaders suspect the military focused on recruiting followers of Musa Hilal in order to create a new border force that would rival Hemetti’s RSF (al-Jazeera, May 3). The new force could incorporate Musa loyalists returning from work as mercenaries in Libya. Mahmud Madibbo, who is the nazir (paramount chief) of the Rizayqat, declared “our total rejection of the campaigns of recruitment of tribal youth by intelligence agencies working to mobilize the tribes for more war and prolong the tribal conflict that has claimed a number of innocent lives” (Sudan Tribune, March 16). The latest in a long line of powerful Rizayqat chiefs, Mahmud is a supporter of Hemetti and vowed last year to protect him.

Rizayqat elders met in 2020 with leaders of the RSF, but were unsuccessful in working out the differences between Musa Hilal and Hemetti. Relations between their respective branches of the Rizayqat, the Mahamid and the Mahariya, became tense after the violent 2017 clashes between Musa’s Mahamid supporters and the RSF, in which Hemetti’s brother, Brigadier ‘Abd al-Rahim Juma’a Daglo, was killed. Musa Hilal served four years in prison after being charged with attacking government forces, although he was pardoned and released by the post-revolution transitional government in March 2021.

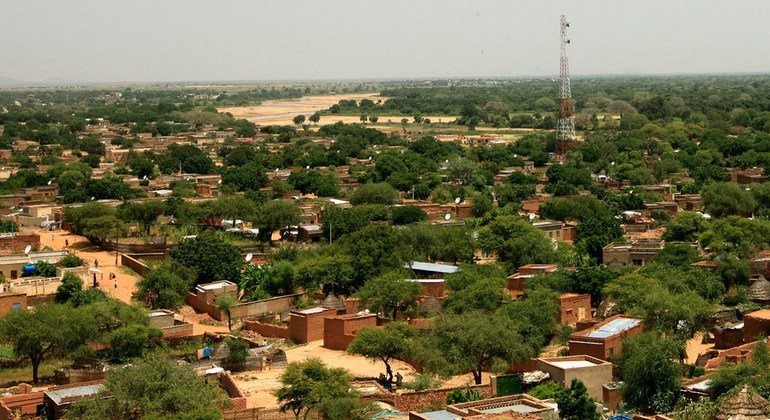

The Destruction of al-Geneina

Al-Geneina, the capital of West Darfur state, is home to nearly half a million people. Escalating violence, much of it ethnic-based, forced the West Darfur governor to declare a State of Emergency and a 7AM to 7PM curfew on April 10, five days before the conflict between the RSF and SAF broke out. Arab gunmen on motorcycles and camels were reportedly attacking the eastern part of al-Geneina, burning houses and shooting randomly at people. Security forces were conspicuously absent from the streets (Sudan Tribune, April 10).

Al-Geneina in Peacetime (UN News)

Al-Geneina in Peacetime (UN News)

By late April, the police and much of the regular army had fled as armed Arab tribesmen began to pour into al-Geneina from north and central Darfur. Indiscriminate fire killed many, camps for displaced people were overrun and medical facilities, including the Red Crescent headquarters, were looted and burned, destroying blood banks and valuable medical equipment (Sudan Tribune, April 27). All dialysis patients in al-Geneina died after equipment and medicines were looted (Darfur24, June 10). Al-Geneina airport has since closed, which prevented the arrival of humanitarian assistance.

Al-Geneina Now (Mail and Guardian)

Al-Geneina Now (Mail and Guardian)

Doctors and other health workers have fallen victim to snipers and the generators needed to power emergency clinics have been stolen by gunmen. Markets, government buildings, schools and aid agencies remain closed after being looted and the water system, communications and power grid have been disabled (Middle East Monitor, May 26). Many private homes have been destroyed. Areas where residents have taken refuge in large numbers have come under attack by RSF forces firing RPGs (Radio Dabanga, June 14). Other African groups besides the Masalit are also being attacked in al-Geneina by Arab militias backed by RSF forces under the command of ‘Abd al-Rahman Juma’a. Hundreds of bodies lie in the streets as snipers prevent anyone from going outside. Rape, arson and armed robbery have become common (Darfur24, June 10). According to West Darfur’s deputy governor, al-Bukhari ‘Abd Allah, “The magnitude of suffering is inconceivable in El Geneina” (Radio Dabanga, June 8).

Masalit and RSF Responses

In the first days of May, Masalit residents were reported to have seized 7,000 weapons from an abandoned police armory in al-Geneina, though a Masalit leader denied responsibility (Sudan Tribune, May 2). Weapons are plentiful and arrive regularly from Chad. However, they are expensive, and only wealthy residents can afford the $1300 it costs to purchase a Kalashnikov (France24.com, May 19).

The RSF has attempted to obscure its part in the violence by insisting, as it has in Khartoum, that men were impersonating RSF personnel during attacks on civilians. The RSF used social media to condemn a May 14 SAF attack in al-Geneina using tanks and heavy artillery that allegedly killed 20 civilians and damaged the Nassim mosque (RSF Twitter, May 14). The paramilitary has also called for an independent investigation into the violence in al-Geneina, and is no doubt confident that no such inquiry can proceed under the current conditions.

Despite the RSF’s role in the fighting, Hemetti issued a message in late May calling on the people of al-Geneina to “reject regionalism and tribalism. Stop fighting amongst yourselves immediately” (Middle East Monitor, May 26). Nevertheless, by June 15, there were over 1,000 dead in al-Geneina, including women and children, with thousands more wounded and unable to receive treatment. Over 100,000 residents have fled across the border to Chad or other parts of Darfur (al-Hadath TV [Dubai], June 15; Darfur24, June 10).

The Murder of West Darfur’s Governor

Governor Khamis ‘Abd Allah Abkar

Governor Khamis ‘Abd Allah Abkar

The governor of West Darfur, Khamis ‘Abd Allah Abkar, was murdered on June 14, only two hours after receiving an interview form al-Hadath TV. During the interview, Khamis denounced the killing of civilians by the RSF and Arab militants in West Darfur: “There is an ongoing genocide in the region and therefore we need international intervention to protect the remaining population of the region” (Sudan Tribune, June 14). Khamis led Masalit self-defense militias during the Arab attacks of the 1990s. Arrested and sentenced to 20 years in prison, Khamis nonetheless escaped in 2003. He then joined the Sudan Liberation Army (SLA) rebel movement but eventually left to form his own breakaway movement, the SLA-Khamis Abakr (SLA-KA) (Small Arms Survey, July 2010). In time, this became the largely Masalit Sudanese Alliance Forces. Khamis was appointed governor of West Darfur after this new group joined four other rebel groups in signing the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement (JPA).

Khamis’ arrest by RSF forces followed his interview, with a short video clip appearing on social media showing the governor being unloaded from a vehicle by armed men, one of whom appears to have tried to attack him with a chair as he was being led into a room (Twitter, June 14). A second video then appeared on social media showing the governor’s bloody body, while unseen individuals celebrate offscreen (Sudan Tribune, June 14). SAF commander General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan accused the RSF of the killing, noting “the dead man had nothing to do with the conflict” (al-Hadath TV [Dubai], June 15). The RSF condemned the murder of the governor. However, an RSF spokesman did not affirm or deny responsibility for the murder, stating only that, “We are in a state of war and there is no safe place in West Darfur” (The New Arab, June 15; Channels Television [Lagos], June 16; SUNA, June 14).

Masalit Sultan Sa’ad ‘Abd al-Rahman Bahr al-Din

Masalit Sultan Sa’ad ‘Abd al-Rahman Bahr al-Din

West Darfur’s traditional leadership has been challenged as well as its political leadership. After Rizayqat gunmen carried out three major massacres of Masalit civilians between 2019 and 2022, killing a total of 378 people, the Sultan of Dar Masalit, Sa’ad ‘Abd al-Rahman Bahar al-Din, complained of the growth of government-sponsored “Arabism,” accompanied by the disarmament of the Masalit and the arming of Arab militias. As sultan (a largely symbolic but influential position), Sa’ad hinted in 2021 that it might be time to re-examine the Gilani Agreement of 1919, which saw Dar Masalit absorbed by Anglo-Egyptian Sudan rather than French-ruled Chad (Darfur24, May 14, 2021). The sultan later complained it would have been better for Dar Masalit to have been absorbed by Chad, which despite being one of the world’s poorest nations, “has a strong security apparatus.” (BBC, May 31, 2022). Masalit tribal leaders have been targeted in the fighting; among the victims is the Sultan’s brother, Amir Tariq. The sultan’s palace overlooking the city was looted and partly destroyed and an Arab fighter was filmed outside the damaged building declaring “There will be no Dar Masalit again, only Dar Arab” (Sudan Tribune, June 13).

Conclusion

With local support from Darfur’s Arab tribes (and across the board support is not guaranteed), the RSF could make Darfur a stronghold in the event that the paramilitary is driven from Khartoum and other Sudanese cities. Mustafa Tambour, leader of the breakaway Sudan Liberation Movement-Tambour (SLM-T), recently reported that goods, vehicles, and cash looted by the RSF in Khartoum are being shipped to parts of central and western Darfur (Radio Dabanga, June 13).

On the other hand, the assassination of Governor Khamis, as leader of one of the five Darfur rebel movements to sign the JPA, has the potential to draw the other rebel leaders into the conflict, especially as violence has spread across the rest of Darfur, where the joint patrols of the JPA signatories have helped, if not maintain security, at least prevent insecurity from becoming much worse. Such joint operations have had less success in West Darfur. When Darfur Governor Minni Minnawi tried on May 24 to deploy a joint force of former rebel groups to escort a commercial convoy into al-Geneina and stop the violence against civilians, for example, his forces were ambushed outside the city by RSF troops supported by armed Arabs (Sudan Tribune, May 24). For the moment, there appears to be little to prevent the further displacement of the Masalit from their traditional homeland.

NOTES

- Daowd Ibrahim Salih, Mohamed Adam Yahya, Abdul Hafiz Omar Sharief and Osman Abbakorah (Masalit Community in Exile): “The Hidden Slaughter and Ethnic Cleansing in Western Sudan: An Open Letter to the International Community,” Damanga.org, April 8, 1999.

- “Situation in Darfur, Sudan,” Case Information Sheet, The Prosecutor v. Abdel Raheem Muhammad Hussein, ICC-02/05-01/12, May 1, 2012, https://www.icc-cpi.int/sites/default/files/CaseInformationSheets/HusseinEng.pdf

This article first appeared in the June 26, 2023 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.