Dr. Andrew McGregor

Military History Online, December 22, 2006

Introduction

Though it solved little at a great expense in human life, the Crimean War of 1853-55 remains a much-studied turning point in military history. Despite its name soldiers and sailors from a variety of nations and empires fought the war on seven fronts; the Danube region, the Crimea, the Caucasus, Eastern Anatolia, the Baltic Sea, the White Sea, and the Kamchatka Peninsula on Russia’s Pacific Coast. With several other nations on the brink of joining in (including Spain, Austria-Hungary, Prussia, Sweden and the United States), the Crimean War very nearly became the first world war. For the combatants its often-disastrous conduct exposed the need for revisions in military tactics, improved medical services and the creation of efficient logistical systems. The Muslim Ottoman Empire entered into an alliance with the Christian nations of Western Europe against Russia, laying the historical groundwork for the eventual presence of modern Turkey as the second-largest military force in NATO. Britain and France’s union against Imperial Russia marked the beginning of an important but occasionally testy military alliance between ancient rivals. Less well known are the roles played by the armies of Egypt and Sardinia on the allied side, but least understood of all is the role of the Tunisian armed forces. Though Tunisia’s contribution of nearly 10,000 troops to two separate fronts is well established, it remains hard to say with any certainty just what the Tunisian expedition actually did there. It is surprisingly difficult to answer even the most basic question; did they fight or not?

Though the Ottomans could be meticulous in other areas, Ottoman military affairs in the 19th century are often so poorly recorded as to astonish Western historians, used to a rich literature of official accounts, archival records, personal memoirs, diaries, correspondence and press accounts surrounding nearly every campaign undertaken by Western armies. Many Ottoman officers were in fact illiterate, while many of those who could record their thoughts might have thought twice about detailing the corruption and intense personal rivalry that plagued the 19th century officer corps. The opinion or memories of the common foot soldier were unsought and in any case considered irrelevant at the time. These problems in historical documentation are typically multiplied in researching the role of Ottoman vassals like Egypt and Tunisia during the Ottoman Empire’s long death struggle.

The Tunisian Army

From the time of the Ottoman conquest of Tunisia in 1574 the Tunisian army consisted mainly of elite formations of Turkish volunteers recruited in Istanbul and a small number of Mamluks. This army was augmented by native auxiliaries and the Zouaves, professional Berber soldiers from Algeria’s Kabylia Mountains. Unlike the large Mamluk establishment in Egypt, there were probably no more than several score Mamluks of any age in Tunisia at the time, and these were often engaged in destabilizing ethnic and political rivalries. Egypt’s own Mamluk establishment was strictly unofficial, Muhammad ‘Ali having destroyed their power in the massacres of 1811. Slaves continued to be imported quietly into Egypt and Tunisia from the north Caucasus until the 1850s, when the Russian conquest of the region eliminated this source of supply.

Typically purchased from the slave markets, young Greek, Circassian or Georgian boys were brought to Tunis where they would be attached to the ruling family or the family of an existing Mamluk, converted to Islam and given a Koranic education and training in the traditional military arts, often leading to manumission (liberation from slavery) and a senior position in the Beylicate’s administration.

The military modernization along European lines achieved by the Ottoman Sultan and the Viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad ‘Ali, did not escape the attention of Tunisia’s ruler, Husayn Bey. The old style Turkish army with its emphasis on flamboyant cavalry and the use of swords, spears and other ‘white arms’ was already severely outdated. The future belonged to the infantryman, drably and cheaply uniformed, and expert only in his drill and the operation of his musket. In January 1831 Husayn Bey established the Nizami (New) army. The drill and uniforms of the new army were European, with training provided by a French military mission. With rare exceptions, only Turks and Mamluks served as infantry officers. The Cavalry (Spahis) were Tunisian with Tunisian officers, acting as a counterforce to the Turkish element in the army. During the 1840s Ahmad Bey (1837-55), expanded the European style army founded by his predecessor. It was to reach peak strength of about 16,000 men before the financial strain of such a large establishment began to overburden the Tunisian treasury. At this time the Nizami army consisted of seven infantry regiments, two artillery regiments, and a small regiment of light cavalry.

The Nizami army suffered from several problems. The infantry was equipped with a variety of outdated muzzle-loading European muskets. There were far too many officers, most of whom knew nothing of military science, while others could not even read or write. Logistics and supplies were carried out by private contractors, an arrangement that was not always satisfactory, as will be seen. Conscription gave the army the numbers it required, but little differentiation was made between the firm and the infirm during recruitment. As in Egypt, the term of enlistment was life, making the visits of conscription details greatly feared by the native Tunisians. Wealthy conscripts could purchase substitutes or short-term enlistments while the urban population of Tunis was made immune from conscription after a public demonstration. At one point an entire regiment was composed of men on 6-month short-term enlistments. In a military sense it was useless, but may have served as a means of subsidizing the other regiments.

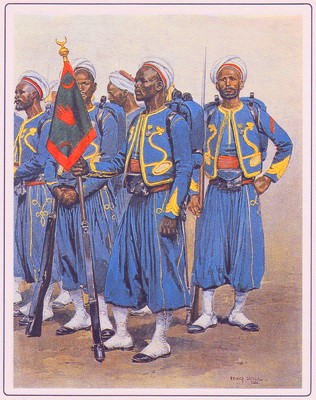

Tunisian Troops, Crimean War Period

Tunisian Troops, Crimean War Period

Among Ahmad Bey’s social reforms were the abolition of the slave trade in 1841 and the emancipation of all Tunisia’s slaves in 1846. Many of these new freedmen may have sought employment in the Bey’s army. In 1837 an attempt was made to recruit an army entirely from black freedmen. The project soon fell apart when a Tunisian general decided ‘recruitment’ meant seizing every black man in Tunis, slave or free, and herding them into a barracks like cattle. The project was soon abandoned after the scandal. During Ahmad Bey’s reign conscription was applied for the first time to the native Tunisians, who at first greatly resented this violation of the social structure of Tunisian society, in which the ‘Turks’ were entirely responsible for military affairs.

Ahmad Bey was in a precarious position, with the expanding French empire to his west in Algeria, and an Ottoman army to the east in Tripoli. Like his more powerful counterpart in Egypt, Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha, Ahmad Bey began to play Britain and France off each other while increasing his symbolic and practical independence of Istanbul without going so far as to renounce allegiance to the Sultan. France encouraged Ahmad Bey’s independent streak, knowing that an independent Tunisia might eventually be more easily severed from the Ottoman Empire and added to French North Africa when the time came. A French military mission was sent to aid Ahmad Bey’s formation of a modern army, and the Bey was even received as a head-of-state on a visit to France in 1846.

Raising the Expeditionary Force

The finances of the beylicate suffered a severe blow in 1852 when one of Ahmad Bey’s ministers secretly obtained French citizenship and then fled to Paris with most of the treasury. The timing couldn’t have been worse as the whole country was suffering from the economic impact of several years of failed crops. Ahmad Bey suffered a stroke in 1852 and by January 1853 was forced to disband most of an army he could no longer afford. Only the Mamluks and a small bodyguard of mostly Turkish professional soldiers remained.

The ‘Crimean’ War actually began with the May 1853 Russian invasion of the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, under Ottoman suzerainty. The Sultan and his council did not declare war until October 1853. When the Ottoman Empire found itself at war it traditionally called on its vassals for military contributions. To everyone’s surprise, Ahmad Bey responded positively to the Sultan’s call despite having no army to send. The Bey sold his personal jewelry and arranged for European loans to finance the raising of new regiments of infantry, cavalry and artillery for the Crimean campaign. Training of the new recruits appears to have been perfunctory, though many of the first draft of soldiers were likely rehired veterans of the units disbanded in 1853. France initially opposed Tunisian participation in the war, fearing that such a gesture might be the first step to closer ties to the Istanbul government, thus undoing all France’s efforts to promote a schism between the two.

The rapid mobilization of the Tunisian army remains a puzzle. Starting virtually from scratch, the first part of the expeditionary force sailed from Tunis only two months after the Bey made the official announcement of Tunisia’s intentions on May 10, 1854. Even more surprising is the fact that the French military mission was not asked for its assistance in mounting this enormous effort, which, moreover, was opposed by many of the Bey’s ministers. One might suppose that the Bey devoted his full energies to the project, but in fact Ahmad Bey was suffering from partial paralysis as a result of his stroke and could not even address the troops. Yet despite all odds the army sailed in good order in record time. Most likely it was an enormous effort by the Bey’s devoted Mamluks that was responsible for the rapid mobilization. Chief among these would have been Mustafa Khaznadar (a Greek Chiote brought as a slave to Tunisia in 1821while still a boy) and a Georgian Mamluk named Rashid, who took command of the expedition. Devoting himself to the study of military science, Rashid was a chief military commander and advisor under Ahmad Bey.

We can assume with such a short preparation time the organizers would have fallen back on what they already knew, organizing the expeditionary force along the same lines as the old army, i.e., regiments of Arab Nizami and Berber Zouaves led by Mamluks and professional Turkish soldiers. Haste and enthusiasm are poor substitutes for proper training, and even though most of the recruits were probably veterans of the disbanded elements of the Nizami, it is impossible to believe that the Tunisian force was in any way combat ready. This does not preclude their being thrown into the cauldron of battle soon after their arrival; they would not be the first or the last untrained unit to be thrown into the frontlines.

The independent kingdom of Sardinia was another small state eager to play an international role, contributing troops to the anti-Russian alliance. Sardinia was a strange partner to Tunisia, the two having nearly come to war in 1833 and again in 1844. Sardinia had once been prey to the powerful corsairs of Tunis, and at times seemed keen to provoke a conflict with now much-weakened Tunisian Beys. Sardinia joined the war in January 1855.

Tunisians at Balaklava?

As Balaklava’s first line of defence, a series of timber-reinforced earthworks known as redoubts was built by Ottoman troops, each armed with several guns. The work was done under the supervision of Major Charles Nasmyth, a British officer of the Royal Engineers who had led the successful defence of the Ottoman forts at Silistria on the Danube front earlier in the year. Evidently the Allied command was intent on a repeat performance. The redoubts were built overlooking the valley about two miles from the town of Balkalava. They were thus the first to detect a large movement of Russian troops under General Pavel Liprandi (a veteran of the 1812 campaign against Napoleon) towards the town on the morning of October 25. The most important redoubt, No. 1, with 600 men and three guns, was placed on a point known as Canrobert’s Hill, named for the French commander. Spaced about 500 yards apart, Redoubts 2, 3 and 4 had 300 men and 2 guns each. Two additional redoubts remained unfinished at the time and played no part in the battle. One source suggests that Liprandi learned in advance that the redoubts were occupied by second-line troops, drawn from Turkish militias, the Tunisians and various untrained recruits.

There are varying accounts as to how stiffly Redoubt No. 1 was defended. Some maintain that the Ottoman troops fired only a few rounds before abandoning the redoubt and their guns to the advancing Russians. Others suggest a one to two hour-long battle that began with a barrage by thirty Russian guns, followed by a massive infantry assault by the Azov and Dneiper Regiments. The latter version seems to have been confirmed by General Liprandi’s claim that 170 men of the redoubt’s garrison of 600 were found dead when the Russians entered, and Russian eye-witness account that describe a shower of bullets and shells that inflicted heavy losses on the Azov Regiment. (By comparison, 134 men were killed of the 658 that rode in the charge of the Light Brigade later that day). Ottoman losses suggest nothing less than a determined defence of the position before it was abandoned.

In each Ottoman redoubt was a British NCO of the Royal Artillery to supervise the operation of the guns. When the outnumbered troops of Redoubt 1 broke the NCO had the presence of mind to spike the guns before leaving. The Russians ran a battery of four guns up into the redoubt and began to fire on Redoubt No. 2. The sight of their comrades streaming out of Redoubt 1 was enough to convince the men of Redoubt 2 to do likewise as the Ukraine Regiment advanced on their position. Their retreat was a strange spectacle as the men left at a leisurely pace, encumbered by their belongings and various items of equipment like pots and pans. Again it was up to the British artillerymen to spike the guns. The redoubts now began to collapse like a house of cards as the Russians kept moving their artillery into each captured earthworks to fire on the next. As the Odessa Regiment moved up in columns Redoubt 3 was abandoned, and then Redoubt 4. It was not long before the Ottoman soldiers dropped their arms and possessions in favour of full flight as they found themselves raked by Russian artillery fire or run down by the merciless pikes of the Don Cossacks. At a time when the loss of artillery was considered shameful, the Ottomans had abandoned a great deal of ordnance after barely using it (one source claims that many of the shells sent to the redoubts were the wrong caliber). That the nine lost 12-pounder guns had all been on loan from the British compounded the problem.

The evacuation of Redoubts 2, 3 and 4 in front of the French and British armies destroyed the reputation of the Ottoman army in only a few minutes. This was probably unfair. Once Redoubt 1 (the right anchor of the defensive line) fell, there was no chance of holding Redoubts 2 to 4. These hastily built fortifications held only a combined total of 900 men with six guns. The Russian force heading for the redoubts consisted of 15,000 men, 4,000 cavalry and nearly 80 guns, many of a higher caliber than the Ottoman twelve-pounders. Apart from a battery of British artillery that was run up and quickly destroyed during the Russian barrage, no help was forthcoming from the British army. Despite intelligence warnings of an attack, the allies had been caught off guard, with many senior officers (including the allied commander Lord Raglan) arriving hours late to the battlefield. It was only the concerted defence of Redoubt 1 that bought the allied armies enough time to deploy, but this did not prevent Lord Raglan from suggesting in his official report of the battle that the men of Redoubt 1 had fled without a fight. Raglan, like Times correspondent Peter Russell, arrived only in time to see the Ottomans fleeing Redoubt 2, both assuming in their dispatches that Redoubt 1 had been abandoned the same way. Lord Lucan (the British cavalry commander) witnessed the assault and is reported to have praised the defence of Redoubt 1 to his Turkish interpreter.

In the second line of defence Scottish General Sir Colin Campbell lined up his 93rd Highlanders and a company of about 100 men from the Invalid Battalion midway between the town and the redoubts. Sir Colin managed to stop some of the soldiers fleeing from the redoubts and formed them up on his flanks. When the Russian cavalry reached a point 600 yards from their line (well out of range) the Ottoman troops fired a useless volley and turned to their heels, heading for the ships in the harbour.

Following Sir Colin’s orders, the Highlanders laid concealed in the high grass of the ridge before they shocked the fast-moving Russian cavalry by rising and firing their first volley with the Russians barely in range. With little time to reload and no other defence than their bayonets against this raging mass of hooves and steel many units would have broken at this point. The Highlanders allowed their discipline and training to take over, reloading their rifles even as the Russian horsemen bore down on their ranks. A second volley was delivered with devastating effect at 150 yards, forcing the cavalry to turn back. The performance of the ‘Thin Red Line’ of the Highlanders (as it became popularly known) provided an unfortunate comparison to the flight of the Turkish troops, who (as far as many in the allied armies were concerned) abandoned well defended positions against the same cavalry the 93rd repelled in the open field.

Now the subject of near universal scorn and abuse from the allied forces, a breakdown in Ottoman morale was quickly followed by a breakdown in the soldiers’ health. In the filth and mud of their positions near Balaklava typhoid began to run through an army already decimated by cholera on the Danube Front. The un-afflicted were often reduced to begging or pilfering from Allied supplies. The inefficiency of the Allied supply system meant that British and French soldiers also suffered (indeed, the British army was in rags and often shoeless by December), but there was almost unanimous consensus that no one’s plight was worse than the Ottoman foot soldier. With their pay in arrears and the allied commissariat unwilling to extend credit to ‘Turks’, the soldiers were unable even to buy tobacco, their lone consolation. The pork and rum that were a normal part of Allied issue were declined on religious grounds, but only a small increase in biscuit was given as compensation. Still, there was little sympathy from the British and French ranks, most of whom were engaged in their own desperate struggle to survive the winter. By this time they had come to regard the Ottoman soldiers as useless non-combatants and a drain on supplies during that terrible winter. In his diary British officer Henry Clifford (V.C.) recorded the plight of Ottoman troops in January 1855, when allied sentries were routinely found frozen to death in the morning:

The poor Turks, though I believe I am the only one in the Army, who has any pity for them, are fast disappearing. The paths leading to water are no longer dotted with them. Everyone has a blow or a kick for the poor fellows, and nothing but brutal hard language. They are broken hearted, despised, neglected, ill-treated, miserable men.

So who were the men in the Balaklava redoubts? Ottoman records do not seem to exist and British accounts rarely distinguish between Ottoman Anatolian, Egyptian or Tunisian, all simply being ‘Turks’. One possibility is that Turkish regulars occupied Redoubt 1, while second-line troops (including the Tunisians) held the other earthworks. Very plainly the men of redoubts 2, 3 and 4 were not the Turks and Egyptians of the Ottoman Army of the Danube who had repulsed attack after attack on the Silistrian forts. Redoubt 1 was furthest from the allied armies and the struggle for this position may have been difficult to see from the allied lines. Because of the nature of the terrain different parts of the Allied army could at any one time see parts of the battlefield but not others, depending where they were positioned. This was an important contributing factor to the confusion behind the charge of the Light Brigade a few hours after the battle for the redoubts.

It is not unlikely that Tunisians were present in the redoubts. The expeditionary force, after all, had been sent to fight, not to watch battles. The political element of the expedition was to demonstrate Tunisia’s interest in joining the world of modern nations by making an appreciable contribution to an important international effort. Did the Tunisian commander Rashid persuade the Ottoman command to place his freshly arrived troops in the redoubts at Balaklava? He may not have needed to argue too hard; Ottoman practice was to keep experienced troops in reserve. Politically motivated deployments of this type did not take into account the actual capabilities of the soldiers. Many of the Tunisians would have had some experience in raids and desert skirmishes while others would have had little experience of any kind of fighting. The hasty training the expeditionary force received before departing for Crimea would have been inadequate preparation for standing fast before disciplined columns of Russian infantry supported by a large number of guns.

The Last Campaign

The fall of the Russian fortress at Sevastopol in the summer of 1855 is often regarded as the final act of the Crimean War, but for the Ottoman forces the war with Russia went on. Russian troops had descended from the Caucasus to enter the Anatolian heartland of the Ottoman Empire, capturing a number of cities and besieging an Ottoman army at the fortress of Kars. To relieve pressure on the Anatolian front the Allied command decided to allow the Ottoman Army in the Crimea to cross east across the Black Sea to the Caucasus, where Circassian Muslims were fighting a losing battle to repulse invading Russian armies. As British, French and Sardinian troops were loaded on transports for the return to Europe, British steamers began shipping the Ottoman forces to a new front. With Omar Pasha at their head, a 45,000 strong army of Turks, Egyptians and Tunisians disembarked at the Black Sea ports of Sukhum-Qal’a and Batoum through September and October of 1855. If the expedition was to have any success it had to come before the arrival of the autumn rainy season, but the march into the interior was slowed by mud and the difficulty of passing through thick forests.

Correspondent Laurence Oliphant encountered a group of Tunisians at Zikinzir, close to the main Ottoman camp at Batoum: “We found ourselves surrounded by swarthy Arabs, who, peering out of their huts, looked like the slaves of some tale in the Arabian Nights. The officers were as black as the men; and a Negro colonel told us that these were Tunisian troops waiting for the arrival of Omer Pasha.” Oliphant’s description suggests that at least part of the Tunisian expeditionary force consisted of Black African troops. None of these men appear to have been involved in the Balaklava fiasco; given the racial attitudes of the time it seems impossible that some of the more vitriolic European accounts of the ‘Turks’ abandoning the Balaklava redoubts would not have mentioned the sight of ‘negro troops’ fleeing their posts.

Omar Pasha led an Ottoman column into the heavily wooded interior. The Ottomans finally encountered the Russian army at the Ingur River, where the campaign’s only battle of note was fought. The confused battle in the forest was a small triumph for the Ottomans, but ultimately spelled the doom of the expeditionary force as it only encouraged Omar Pasha to continue into Georgia. Kars fell to the Russians at the end of November, but the news was slow to reach the Ottoman commander. Ironically it was news of Omar’s arrival on the Black Sea coast that led the Russians to intensify their attacks on the fortress. It was late in the season, already inefficient supply-lines were overstretched, and now the rains came, turning the landscape into a sea of thick mud. The army turned back for the coast, struggling through the quagmire with little food or leadership, the officers having followed Omar Pasha’s example by heading for Sukhum-Qal’a well in advance of the rest of the army. Those soldiers not felled by disease, exposure, starvation or the constant attacks by Georgian partisans were shipped home after they straggled in to the coast. The last campaign of the Crimean War was at last over.

Conclusion

When the much smaller expeditionary force returned in 1856 its members were awarded a silver campaign medal. At this point the force was dissolved, with nobody apparently interested in recording their contribution to the war. The last contingent of troops sent after Ahmad’s death by his successor Muhammad Bey was probably viewed as part of the traditional presentation of gifts to the Ottoman Sultan before the official investiture of the Tunisian Bey.

Though Ahmad Bey made unusual efforts to ensure the well-being of the expeditionary force in the field, it seems that the sums he provided for this purpose never made it through the Ottoman chain-of-command. There is no indication that the Tunisians suffered any less than the Turks and Egyptians in the Crimea. The usual arrangement for vassal expeditionary forces in Ottoman campaigns was for Istanbul to take care of all the troops’ needs on campaign, including pay, uniforms, arms, ammunition, food, etc. In practice a remarkable inefficiency and widespread corruption in the Ottoman officer corps meant that little reached the soldier in the field. Perhaps aware of these deficiencies, Ahmad Bey made private arrangements with Tunisian merchants in Istanbul to supply the expeditionary force with whatever supplies they needed. Judging from the 40% of the force who died from disease or exposure in Batoum it seems safe to say that, for whatever reason, few if any of these supplies reached the army.

If the Tunisians did not fight beside the Turks and Egyptians at the Ingur River either (and there is no evidence they did), then where were they? Had they been left behind at Batoum because of their poor performance at Balaklava? If there was no intention to use them on the campaign then it would seem rather pointless to ship them on to the Caucasus from the Crimea rather than returning them home, though trying to apply logic to the deployments of the 19th century Ottoman Army can be a fruitless exercise. In defence of the Tunisians there is no mention in any official dispatches from the front regarding poor behaviour on the part of the Tunisians. There are French accounts claiming (without documented evidence), that the Tunisians mutinied in Batoum when they realized they had been left to die of disease and exposure without any opportunity to fight. Other French accounts, including official reports, state that the Tunisians performed well, though what they were doing well is not stated.

If, as so often reported, the Tunisian expeditionary force was left to die of disease in their camps without ever fighting, it must have been a fatal blow to Ahmad Bey, who had invested his wealth and reputation in fielding the expedition. The Tunisian role at Balaklava cannot be confirmed, and if the troops fought elsewhere they apparently did little one way or the other to merit mention by observers. Ahmad Bey’s successors allowed the military to decline into a disgraceful state and in 1881 Tunisia fell to the French without a fight.

| Footnotes

[1]. Ian Fletcher and Natalia Ishchenko, The Crimean War: A Clash of Empires, Staplehurst Kent, 2004, p.159) [2]. NF Dubrovin, Istoriya Krymskoy Voiny Oborony Sevastopolya II, St. Petersburg, 1871-74, pp.129-30) [3]. Henry Clifford, His Letters and Sketches from the Crimea, London, 1956 [4]. Parts of this article rely upon L. Carl Brown’s important history of 19th century Tunisia; The Tunisia of Ahmad Bey: 1837-1855 (Princeton, 1974). Brown refutes the possibility of a Tunisian presence in the redoubts of Balaklava as a rumour, but does not seem to be aware of contemporary British accounts of Tunisians in the battle (such as George Dodd: Pictorial History of the Russian War, 1854-56, Edinburgh, 1856). Indeed, Brown may have contributed to the evidence for Tunisian participation by citing the November 27, 1854 report of the American Consul in Tunis, which describes Tunisian troops fleeing the Balaklava redoubts without firing a shot. Brown refers to the report as “a myth.” [5]. Laurence Oliphant: The Trans-Caucasian Campaign of the Turkish Army Under Omer Pasha, London, 1856 |

http://www.militaryhistoryonline.com/19thcentury/articles/tunisiacrimea.aspx