Andrew McGregor

October 27, 2017

Life in parts of Kenya’s traditionally Muslim coastal region has become a nightmare of beheadings and midnight raids by masked assailants, compounded by the ineptitude of local security forces. In Lamu County, an historic center of Swahili culture, growing ethnic and religious tensions have proved fertile ground for the spread of a Kenyan offshoot of Somalia’s al-Shabaab terrorist group. The struggle for Lamu is not an unfortunate but obscure episode in the war on terror however; it is a battleground for the economic prosperity of East Africa.

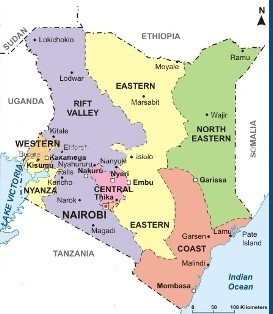

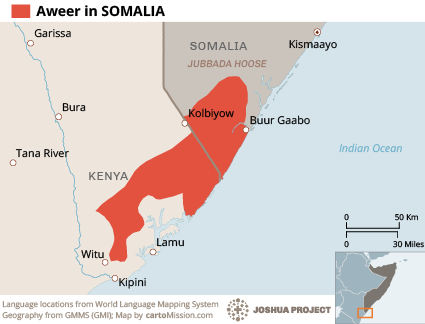

Lamu County (Somaliupdate.com)

Lamu County (Somaliupdate.com)

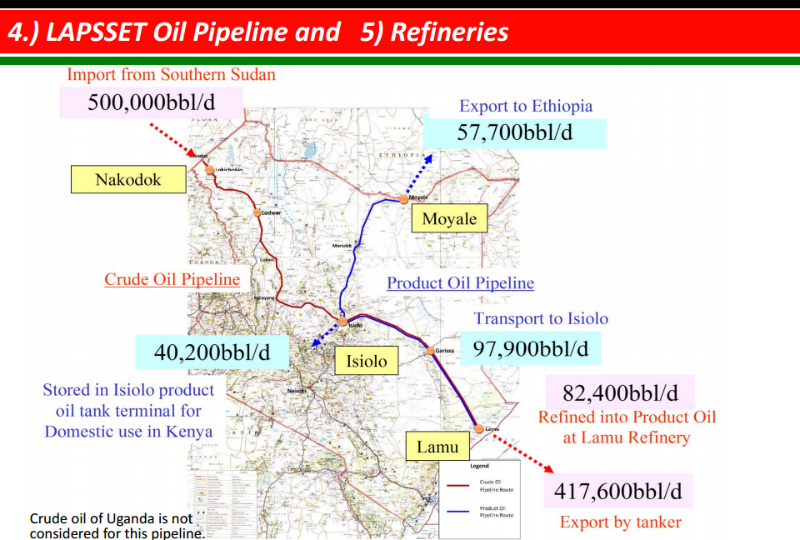

Lamu County is the planned site of one of the most ambitious economic initiatives attempted in Africa – the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia-Transport Corridor (LAPSSET), a $24.5 billion project creating a network of roads, rail-lines and pipelines connecting South Sudan, Uganda, Ethiopia and Kenya, with the additional construction of three resort cities and a modern port and refinery at Lamu.

The county faces the Indian Ocean. It is culturally and religiously distinct from most of inland Kenya and traditionally Sunni Muslim, with an emphasis on Sufism. The county is divided into two parts – the mainland sector, and a region of 65 islands once prosperous from the trade in slaves and other products of the African interior. The largest economic activity is tourism, mostly restricted to the centuries-old Swahili trading ports on the islands. On the mainland, locals rely on agriculture, fishing and mining.

The local population consists of Swahilis, the dominant culture formed by a mixture of Bantu peoples with Arab and Persian traders that began in the 9th century; Orma, related to the Oromo of Ethiopia, Somalia and northern Kenya; Bajuni islanders; and the Aweer and Watta, both traditional hunter-gatherer groups.

Politically uninfluential and subject to ethnic and political violence in recent years, the region has been designated an operational security area since September 15, 2015. Social services such as healthcare and education are lacking, fresh water is scarce, food supplies are insecure and unemployment is high. [1]

Much of the region’s violence is the result of a strategy by al-Shabaab to punish Kenya on its own soil for initiating an operation by the Kenya Defense Force (KDF) – named Linda Nichi (Swahili for “Protect the Country”) – against al-Shabaab within Somalia in October 2011. The operation’s declared intent was to stifle cross-border incursions by Somali militants. In practice, however, the deployment has created a Kenyan-controlled buffer zone known as Jubaland in southern Somalia.

The Mpeketoni Massacre

On June 15, 2014 al-Shabaab struck Lamu County, massacring 65 men, mostly Kikuyu Christian migrants from inland Kenya. The local police station offered no resistance and was quickly overrun, the police fleeing, leaving behind their weapons, which were collected by the attackers. Despite the presence of nearby police and military installations, the attack continued for ten hours without interference from security forces, who were apparently watching a broadcast of a FIFA World Cup soccer match.

Al-Shabaab claimed the massacre was in response to the “Kenyan government’s brutal oppression of Muslims in Kenya through coercion, intimidation and extrajudicial killings of Muslim scholars” (Daily Nation [Nairobi], June 16, 2014).

Rather than address the al-Shabaab threat, Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta, a Kikiyu, attempted to shift blame for the attack to opposition politicians, claiming the massacre had nothing to do with al-Shabaab, despite al-Shabaab claiming responsibility for the attack on its official Twitter account earlier the same day (Reuters, June 16, 2014; Daily Nation [Nairobi], June 16, 2014). Kenyatta also claimed that local police had received advance warning of the attack but ignored the warning (BBC, June 18, 2014).

Ethnicity is a relevant factor here. During the 1952-1960 colonial-era Mau Mau rebellion, British administrators used the Mpeketoni region for the resettlement of Kikiyu from Kenya’s Central Highlands where the rebellion was concentrated. Mpeketoni was later used as a resettlement site for Kikiyu farmers who had returned to Kenya from Tanzania in the 1970s. These transfers of members of Kenya’s largest and most powerful ethnic group created a lasting turbulence over land ownership issues and turned the Muslim Swahili community into a religious and ethnic minority in their traditional homeland. [2]

Typical of more recent attacks in Lamu County was one conducted on the evening of September 5-6, when terrorists in military gear struck two villages in the Hindi district of Lamu. Calling residents out by name, the gunmen beheaded four individuals in front of their wives and children before fleeing into the Boni Forest. Protests the next day over the security forces’ inefficiency were broken up by riot police (The Standard [Nairobi], September 6). The Hindi police chief was later suspended for sleeping on the job (Daily Nation [Nairobi], September 11).

Operation Linda Boni: Security Failure in Lamu County

Kenya’s counter-insurgency effort in the region, Operation Linda Boni, began in September 2015 and was expected to last 90 days (Daily Nation [Nairobi], November 16, 2015). Operation Linda Boni is now in its third year, despite repeated pronouncements that all its objectives have been achieved. The operation involves a number of security agencies, including the KDF, the National Police Service, the Administration Police and the National Intelligence Service (NIS). Agents of the latter infiltrate the villages to identify supposed terrorist collaborators.

Despite the operation’s massive expense, the Boni Forest, used as a base by Islamist militants, is still far from secured even though US special forces reportedly provide logistical and training support to Kenyan troops operating there (The Star [Nairobi], February 10; Daily Beast, August 2). The multi-agency operation suffers from infighting, poor coordination and inappropriate equipment. Mounting casualties have demoralized police and soldiers who have little to show for their efforts, and the increasing tempo of attacks in Lamu County has alarmed Kenyan security officials.

Coast regional coordinator Nelson Marwa, an outspoken security hardliner, made some pointed criticisms of the Operation Linda Boni: “We have the Operation Linda Boni in place. It is now almost two years and the way things are, it’s like we haven’t achieved the objective of flushing out criminals inside the forest… How do al-Shabaab find their way past our forces … to get into villages, kill people and go back into the same forest or cross the same borders where our KDF soldiers are? We have enough airplanes and I wonder why most of them are just lying in the bases instead of being put out there to patrol these places. People must be [held] responsible…” (The Nation [Nairobi], September 10).

Lamu County Commissioner Gilbert Kitiyo responded by claiming, without documentation, that the operation had reduced al-Shabaab’s capacity to mount attacks by 80 percent (Daily Nation [Nairobi],

September 20). On October 5, Operation Linda Boni director Joseph Kanyiri announced the al-Shabaab presence in Lamu County was “almost at zero level” (The Star [Nairobi], October 6).

LAPSSET: East Africa’s Economic Hope

In a region already beset by land ownership disputes, the LAPSSET project has led to rampant speculation and fraudulent land transactions. The project is being implemented without consultation with the local community and is expected to bring an influx of one million migrants to the region, few if any of them Muslims. It will be a massive and irreversible demographic shift that al-Shabab’s Jaysh Ayman unit is already exploiting to recruit local Muslims.

Despite government promises, local benefits of LAPSSET are already proving illusory. A presidential directive to LAPSSET to provide 1,000 scholarships worth $550,000 to train local youth on the technical aspects of port operations was ignored by the agency, which provided only ten scholarships worth $17,000 to non-locals (Business Daily [Nairobi], September 17).

Despite government promises, local benefits of LAPSSET are already proving illusory. A presidential directive to LAPSSET to provide 1,000 scholarships worth $550,000 to train local youth on the technical aspects of port operations was ignored by the agency, which provided only ten scholarships worth $17,000 to non-locals (Business Daily [Nairobi], September 17).

The construction of Kenya’s pipeline to Lamu from the oilfields in Turkana County is also now in jeopardy after its budget was cut by 70 percent to help pay for a court-ordered repeat of the fraud-plagued presidential election on October 26, and the failure to pass the 2015 Petroleum Bill after President Kenyatta attempted to cut local communities’ revenue shares in half (Business Daily [Nairobi], October 8).

Al-Shabaab’s Kenyan Affiliate

Though directed by Somalia’s al-Shabaab movement, Jaysh Ayman (“Army of the Faithful”) presents itself as a local movement defending Swahili Muslims while fighting a corrupt Kenyan government and pursuing the creation of a caliphate on the Kenyan coast. As well as night attacks on settlements, Jaysh Ayman has struck power infrastructure and frequently ambushes cars, passenger buses and trucks on highways running through Lamu County (The Star [Nairobi], August 8; Standard [Nairobi], August 2; The Star [Nairobi], August 7). Security on the main roads has grown so bad that vehicles can only move safely in police-escorted convoys.

Mallik Alim Jones (il Giournale.it)

Mallik Alim Jones (il Giournale.it)

As well as hundreds of Kenyan Muslims, Jaysh Ayman includes foreign fighters. Maalik Alim Jones, a Maryland native and Jaysh Ayman volunteer, was arrested in December 2015 while trying to board a boat from Somalia to Yemen. A convicted child abuser who abandoned his family in the US to join al-Shabaab, Jones pleaded guilty to various terrorism-related charges on September 8 (Baltimore Sun, January 18, 2016; September 8).

Andreas Martin Muller (left) and Thomas Evans

Andreas Martin Muller (left) and Thomas Evans

Jones was a suspect in the Mpeketoni massacre and appeared in an al-Shabaab propaganda video before joining an unsuccessful June 14, 2015 attack on a KDF camp in Lamu County (Daily Nation [Nairobi], January 12, 2016). Also prominent in the video was a 25-year-old English al-Shabaab volunteer and convert to Islam, Thomas Evans (aka Abd al-Hakim, or “the White Beast”), who was killed in the attack. [3] Evans, who married a 13-year-old Somali girl and gained a reputation for beheading Christians, is seen in the video greeting a German fellow convert and al-Shabaab fighter, Andreas Martin Muller, (aka Abu Nusaybah, or Ahmad Khalid) (Express [London], June 25, 2015; Telegraph, October 11, 2015). Eleven other Jaysh Ayman members were killed in the firefight, including Luqman Osman Issa (aka Shirwa), who is believed to have directed the Mpeketoni massacre (Reuters [Nairobi], June 15, 2015).

Weak Security Response

A particularly effective al-Shabaab tactic involves ambushing rescuers after a poorly protected armored personnel carrier (APC) has struck a mine. As anger over poor equipment grows in the ranks, the government has promised to purchase and deploy mine-resistant ambush protected (MRAP) APCs.

The militants make extensive use of roadside improvised explosive devices (IEDs) to dissuade security forces from patrolling. The bombs take a steady toll on security personnel who remain helpless against an invisible enemy. The Chinese-made VN-4 “Rhinoceros” multi-role light APCs, in use by government forces, protect only against small arms fire. In addition, they are poorly ventilated, making them unsuitable for use in the hot and humid conditions of the coast. The only other export customer for the VN-4 is Venezuela, which has used them extensively against civilian protesters but not in combat situations.

Thirty of the VN-4 APCs were purchased in February 2016 after widespread criticism of the capabilities of Serbian, Chinese and South African-made APCs obtained through a corruption-plagued procurement system (The Standard [Nairobi], June 1, 2017; Defence Web, June 26, 2014). The VN-4s are deployed by the General Service Unit (GSU), a paramilitary unit within Kenya’s national police that dates back to the Mau Mau uprising. Many GSU members have received Israeli training, while some officers have been trained in the UK.

In partial fulfillment of the government’s promise, 35 CS/VP3 “Bigfoot” APCs were delivered to the government by China’s Poly Technologies in January 2017 (Daily Nation [Nairobi], June 11). Classed as MRAP and already in use in Nigeria and Uganda, the APCs were sent to the Rural Border Patrol Unit, established in 2008 after multiple disturbances along the Somali border. The border patrol unit is part of the Administration Police (AP), a paramilitary police force responsible for guarding public buildings and providing a rapid deployment unit for emergency use.

Kenyan officials and security experts have suggested al-Shabaab is being provided with local intelligence by elements within Kenya (Sunday Nation [Nairobi], June 4). This gives the militants an edge over police forces, which are often drawn from Christian inland communities and view the Muslim communities of the Coast with suspicion and distrust at best. The heavy hand of the KDF and other security forces in terms of torture, disappearances and the unsolved murders of dozens of Kenyan Muslim leaders in recent years continues to work against the development of an effective intelligence network in Lamu County. [4]

Sacrificing Boni Forest

An investigation by a Nairobi daily found a number of security agents asserting that intelligence reports from 2012 that described how al-Shabaab was establishing bases in the 517 square mile Boni National Reserve were ignored. The reports detailed how al-Shabaab was bringing in equipment including GPS trackers and night-vision goggles. According to one agent: “We alerted local police to be aware and watch over these dense forests. No one cared” (Daily Nation [Nairobi], July 20).

The Boni Forest canopy is dense, restricting aerial surveillance, and roads are few, limiting the mobility of security forces. Al-Shabaab’s strategic placement of mines and IEDs complicates the efforts of security forces to infiltrate the forest.

Coast Regional Coordinator Nelson Marwa (left) with Coast Regional Police Commandant Larry Kieng (Kevin Odit/Nation Media Group)

Coast Regional Coordinator Nelson Marwa (left) with Coast Regional Police Commandant Larry Kieng (Kevin Odit/Nation Media Group)

Marwa, the Coast regional coordinator, has insisted on the necessity of bombing “that forest completely,” adding in bombastic fashion that he “will enter the forest if others fear going there … I am ready to die while fighting al-Shabaab in the forefront as the commander” (The Star [Nairobi], June 29).

Bombing the Boni Forest, however, poses a risk to its native inhabitants, the Aweer (or Boni), a group of 3,000 indigenous hunter-gatherers whose traditional lifestyle has already been challenged by forced resettlement and a government ban on hunting. The Aweer are now forbidden to enter the forest during military operations, but have not been provided with food aid since last year (Standard [Nairobi], June 18). The forest is also home to several rare endangered species.

Joseph Kanyiri, the director of Operation Linda Boni, has struck back at environmentalist critics of the bombing: “I cannot comprehend why someone feels this way when a number of trees are destroyed in order to save a thousand lives … This is serious business and that’s why I am asking activists and conservationists to stick their necks elsewhere. We are here to protect lives and end terrorism and that will happen at any cost. The Aweer community remains intact and their lives go on. After all, the bombing is happening thousands of miles away from their habitats” (The Star [Nairobi], August 25).

Joseph Kanyiri, the director of Operation Linda Boni, has struck back at environmentalist critics of the bombing: “I cannot comprehend why someone feels this way when a number of trees are destroyed in order to save a thousand lives … This is serious business and that’s why I am asking activists and conservationists to stick their necks elsewhere. We are here to protect lives and end terrorism and that will happen at any cost. The Aweer community remains intact and their lives go on. After all, the bombing is happening thousands of miles away from their habitats” (The Star [Nairobi], August 25).

In reality, the Boni Forest measures roughly 25 miles by 25 miles and the bombing has made it impossible for the Aweer to forage for food or to obtain food from traders who are now afraid to venture into the region.

Putting Pressure on the Government

Al-Shabaab and its Jaysh Ayman offshoot share a determination to expose the weaknesses of Kenya’s security forces, terrorize Christian migrants to the region and inhibit the tourism industry. It seeks to put pressure on the government by creating a general state of insecurity in a part of the country where, as a result of LAPSSET, the administration now has a substantial interest.

On the government side, there is a pattern of corruption constraining action by the security forces, while intelligence is being collected but not acted on. This appears to be a result of lassitude on the part of the security forces and a belief among government officials that the blame for poor performance can be quickly and easily shifted to others.

Even though al-Shabaab’s radical Salafism has little appeal in a region traditionally influenced by Sufist Sunni Islam, the movement is trying to exploit Muslim alienation from the central government and the bitter land issues that are at the core of much of the violence in Lamu County. It is unlikely that al-Shabaab actually believes there is an opportunity to create a caliphate on the Kenyan coast. Instead their real goal is to hold the LAPSSET development hostage and encourage local and regional pressure on Nairobi to abandon the KDF’s deployment in southern Somalia.

Notes

- M. Bradbury and M. Kleinman, “Winning Hearts and Minds? Examining the Relationship between Aid and Security in Kenya,” Feinstein International Center, 2010, http://fic.tufts.edu/assets/WinningHearts-in-Kenya.pdf

- Herman Butime, “Unpacking the Anatomy of the Mpeketoni Attacks in Kenya,” Small Wars Journal, September 23, 2014, http://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/unpacking-the-anatomy-of-the-mpeketoni-attacks-in-kenya

- Captured al-Shabaab video of the dawn firefight is available here.

- Michael Nyongesa, “Are Land Disputes Responsible for Terrorism in Kenya? Evidence from Mpeketoni Attacks,” Journal of African Democracy and Development 1(2), pp. 33-51

This article first appeared in the October 27, 2017 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor