Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report

May 31, 2019

Sudan Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces Operation in South Kordofan (Reuters/Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah)

Sudan Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces Operation in South Kordofan (Reuters/Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah)

There was much joy in Sudan in the dying hours of the presidency of Omar al-Bashir when the dreaded National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) announced they were releasing all political detainees in the country (SUNA, April 11, 2019). While there were many scenes of elated families greeting detained protesters and opposition figures after their release, some detainees never emerged from Sudan’s grim prisons. The absence of members of the armed opposition who were taken prisoner while fighting to overthrow the Bashir regime raises two important questions: Did the regime change, or only the head-of-state? And what approach will the new Transitional Military Council (TMC) use to deal with the well-armed opposition movements still in the field in Sudan’s western and southern regions?

Prisoners of War?

Only days after the military removed al-Bashir, the TMC chairman, General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, was reminded by an opposition delegation that they were still awaiting the fulfillment of his promise to release members of the armed groups (Sudan Tribune, April 14, 2019). Most of these prisoners belong to the major Sudanese armed opposition groups:

- The Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), a Darfur-based group led by Jibril Ibrahim seeking a more inclusive government that is not almost exclusively derived from the powerful Nile-based Arab tribal groups (the Ja’alin, the Danagla and the Sha’iqiya) that have dominated Sudanese politics since independence in 1956. JEM’s leadership and membership is largely but not exclusively drawn from the Zaghawa of northwestern Darfur. Due to the political protests across the country, JEM declined to resume talks planned talks with the Bashir regime in mid-January, declaring they could not “betray the revolution,” though they also feared the talks would be used as propaganda to preserve the regime (Sudan Tribune, January 13, 2019).

- The Sudan Liberation Movement/Army – ‘Abd al-Wahid (SLM/A-AW), a group based in the Jabal Marra mountains of Darfur and led by the Paris-based ‘Abd al-Wahid al-Nur. The SLM/A-AW is largely Fur.

- The Sudan Liberation Movement/Army – Minni Minnawi (SLM/A-MM), a Darfur-based group that has operated out of ungoverned southern Libya for several years as a result of military pressure from the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and a government paramilitary initially formed from former Janjaweed members, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). The leadership and membership is again largely Zaghawa.

- The Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army – North (SPLM/A-N), based in the Nuba Hills of Southern Kordofan and Sudan’s Blue Nile State. Before South Sudan signed a peace agreement with Khartoum in 2005 that would eventually lead to independence in 2011, the SPLM/A as led by Colonel John Garang sought a unified “New Sudan” that would bring the non-Arab majority of Sudan into the central government. With Garang’s death in 2005, South Sudanese separatists gained political and ideological ascendancy, abandoning those parts of the movement still operating in South Kordofan and Blue Nile, both on the northern side of the new border. These parts of the SPLM/A reconstituted themselves as the SPLM/A-North. The movement split in 2017 over leadership differences between ‘Abd al-Aziz al-Hilu (South Kordofan faction) and two other leaders, Malik Agar (Blue Nile faction) and Yasir Arman (then SPLM/A-N secretary-general). Al-Hilu also felt the needs of the Nuba people (who form the majority of the South Kordofan fighters) were not being addressed by the larger leadership (Radio Dabanga, October 23, 2017). South Sudanese president Salva Kiir Mayardit, who continues to struggle to contain a rebellion in South Sudan’s Equatoria region, made efforts to reunite the two SPLM/A-N factions to better negotiate with the TMC after al-Bashir’s overthrow (East African [Nairobi], May 2, 2019). Agar and Arman were both sentenced to death by hanging in absentia along with 15 other members of the SPLM/A-N in March 2014.

The Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF – a coalition bringing together Darfur’s JEM with the two factions of the SPLM/A-N) has declared that the civilian groups discussing the creation of a transitional government are not representative without including the armed opposition, noting the nation’s future security and democratic transition are at risk without their inclusion (Radio Dabanga, April 30, 2019). The armed opposition calls the detainees “prisoners-of-war” (a term never used by the Bashir regime), but admits that, after years of detention in some cases, it is unsure of the condition or whereabouts of many rebel prisoners (Sudan Tribune, April 16, 2019). Four days after Bashir’s overthrow, JEM demanded the immediate release of all “war-related detainees,” warning that their continued detention was “a call for the continuation of the war” that would delay the ability of the Sudanese to “reap the fruits of the revolution” (Radio Dabanga, April 15, 2019).

Last August, the SLM/A-MM complained that one of its leaders, “prisoner of war” ‘Abd al-Salam Muhammad Siddig, had died at Omdurman’s al-Huda prison after torture that resulted in two fractured legs and internal bleeding that proved fatal after medical treatment was withheld. The movement alleged that the prisoners were suffering a “slow death” in close confinement. Accusing Khartoum of violating the Geneva Convention, the statement reminded authorities that “the right of the prisoners to receive medical treatment and follow-up… is a legal right and not a grant from anyone.” (Radio Dabanga, August 15, 2018).

The JEM Prisoners

The Bashir regime was shaken to its core when scores of JEM vehicles crossed the desert from Darfur to suddenly arrive on the outskirts of the national capital in May 2008. The army largely failed to appear in defense of the regime, and the raiders were engaged in running street battles in Omdurman with police and pro-Bashir paramilitaries. As JEM was finally driven out of the capital after a fierce struggle, some 70 JEM members were captured and sentenced to death. When JEM and several other rebel movements declined to sign the 2011 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur (DDPD), the prisoners were unable to avail themselves of Article 60, allowing for the release of prisoners of war (DDPD, p.63, Article 60, subsection 329, May 2011). Though the death sentences were not carried out, the prisoners are alleged to have endured a kind of living death of torture and abuse in cramped and squalid conditions (Radio Dabanga, August 15, 2013; Sudan Tribune, September 8, 2018).

According to JEM, many of the prisoners languished under sentences of death after their 2008 capture in tiny, vermin-ridden cells, with only a daily visit to the toilet and no access to bathing facilities. JEM has charged that the men are prisoners of war entitled to decent conditions by the Geneva Convention (Hudocentre.org, November 16, 2015).

When JEM detainees in North Khartoum’s Kober Prison went on a hunger strike in 2013 to protest their treatment, the Director General of Prisons arrived to deliver a little regime reality to the desperate prisoners: “We’ve got the power, wealth, aircraft, and vehicles that enable us to do whatever we want… It is our right to act any way we want against any person in all of Sudan… If I kill you all nobody would ask me why” (Radio Dabanga, September 1, 2013).

Kober Prison, North Khartoum (AFP)

Kober Prison, North Khartoum (AFP)

Many JEM rebels were released from Kober and other Sudanese prisons after al-Bashir issued an edict on March 8, 2017. As well as those taken prisoner in Omdurman, there were others taken in later battles at Goz Dango, Fanaga, Donki Baashim and Kulbus (Radio Dabanga, March 9, 2017). A sentence of death was lifted from 66 detainees and another 193 granted amnesty. However, in October 2018, Khartoum admitted that seven JEM prisoners and 21 SPLM/A-N prisoners were still being held in Omdurman’s al-Huda prison despite the presidential amnesty of March 2017 (Radio Dabanga, October 11, 2018).

One of those released under the amnesty, JEM field commander ‘Abd al-Aziz Ousher, complained that a number of senior JEM commanders taken at Goz Dango in April 2015 had not been freed by the presidential amnesty (Radio Dabanga, March 9, 2017). Some 180 JEM prisoners taken at Goz Dango were transferred to al-Huda prison in Omdurman in January 2016. Unable to leave their cells, 23 contracted tuberculosis, which went untreated (Radio Dabanga, September 5, 2016).

President Omar al-Bashir Arrives in Goz Dango to Celebrate SAF/RSF Victory

President Omar al-Bashir Arrives in Goz Dango to Celebrate SAF/RSF Victory

A report released on May 30 by the Darfur Bar Association (DBA) says that 235 prisoners belonging to the SLM/A-MM and the SLM/A – Transitional Council (SLM/A-TC, a splinter group of the SLM/A-AW) remain inside al-Huda prison. These prisoners are alleged to have endured “cruel treatment and torture” as well as starvation rations and an absence of medical treatment for tuberculosis and injuries sustained in battle or through torture in captivity (Radio Dabanga, May 30, 2019). These fighters were taken prisoner in a series of running battles against the RSF and SAF in Darfur when the two rebel movements attempted to cross back into Sudan from their temporary bases in southern Libya.

Post-Coup Developments

Following the coup, the TMC quickly declared a ceasefire in the three conflict areas (Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile State), where many rebel groups were already observing a unilateral ceasefire during the protests for fear the regime would make claims the spontaneous protests were actually planned and executed by the armed opposition. That was exactly the approach the regime took under advice from M-Invest, a Russian company with offices in Khartoum operated by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a close associate of Russian president Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin. Darfuri students in Khartoum were rounded up and tortured into confessions that they were provocateurs working for both Israel and the Wahid al-Nur’s SLM/A-AW (BBC, April 25, 2019; CNN, April 25, 2019). The regime, however, had scapegoated Darfuri students for all manner of anti-government sentiment for years, so the familiar accusations had little resonance in the streets.

Lieutenant General Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemeti,” TMC deputy chairman and leader of the notorious RSF paramilitary, made the surprising move of thanking ‘Abd al-Aziz al-Hilu and the SPLM-N for extending their unilateral ceasefire, adding (after years of brutal repression by the RSF) that the armed opposition movements were a part of the larger movement responsible for deposing President al-Bashir. According to Daglo, the TMC has made contact with the armed movements, including Daglo’s bitter enemies in the Fur-dominated SPLM/A-AW (Radio Dabanga, May 1, 2019). The existence of such contacts has not been verified by the armed opposition and Daglo’s sudden respect for the rebel movements seems disingenuous.

Musa Hilal and Darfur’s Arab Rebels

Another group that has not benefitted from the general release is composed of former Janjaweed commander Musa Hilal and his relatives and followers who were arrested in November 2017. The nazir (chief) of the Mahamid Arabs of Darfur (a branch of the Northern Rizayqat), Hilal acted as a senior government advisor in Khartoum before a dispute with the regime led to his return to Darfur in 2014. Once home, he began to reorganize the Mahamid members of the Border Guard Force (BGF) into the Sudanese Revolutionary Awakening (Sahwa) Council (SRAC), an anti-regime vehicle for Hilal’s political ambitions. SRAC cleared out the outnumbered SAF garrisons in northwest Darfur and the Jabal Amer goldfields and began to establish its own administration in these areas.

This direct challenge to Khartoum’s authority demanded a response, which came in the form of a massive RSF assault on Hilal’s headquarters in Mistiriyha. Hilal, his sons, three brothers and some 50 supporters were arrested after violent clashes and sent to Khartoum as detainees. [1]

Hilal and a number of imprisoned supporters began a hunger strike on April 25 to protest their continued detention, which, despite the TMC’s commitment to release prisoners of the Bashir regime, has now lasted one and a half years without trial or contact with their families (Radio Dabanga, April 26, 2019). SRAC issued a statement on May 5 calling on the TMC to release all prisoners of war and political detainees in Darfur and Kordofan (Radio Dabanga, May 5, 2019).

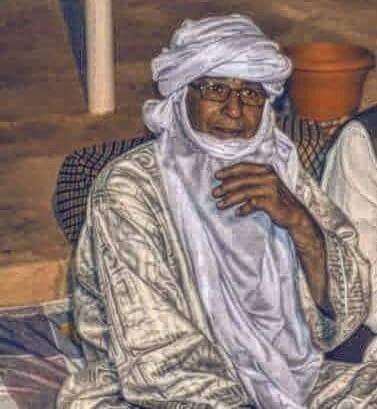

Yasir Arman (in white) with SPLM/A-N Commanders (Radio Dabanga)

Yasir Arman (in white) with SPLM/A-N Commanders (Radio Dabanga)

Yasir Arman Arrives in Khartoum

A “delegation of good intentions” from the SPLM-N Blue Nile faction arrived in Khartoum for talks with the TMC and protest leaders on May 11. SPLM-N Blue Nile deputy chairman Yasir Arman and movement secretary general Ismail Khamis arrived in Khartoum later on May 26 and did not experience any complications at the airport. Arman declared their goal was to “reach a just peace… [and] democracy and citizenship without discrimination and social justice,” while warning the SPLM/A-N would not accept a new military government (Radio Dabanga, May 28 2019). The SPLM/A-N ceasefire has been extended until July 31, unless the TMC chooses to go on the offensive in the meantime (RFI, April 17, 2019).

While waiting for an opportunity to meet TMC representatives, Arman met with US Chargé d’Affaires Steven Koutsis on May 28. This apparently angered the TMC, which ordered Arman to leave the country if he wished to avoid the implementation of his death sentence (Anadolu Agency, May 29, 2019). Arman said he had received no less than five letters from TMC deputy leader Muhammad Hamdan Daglo and one from TMC chairman ‘Abd al-Fatah Burhan demanding his immediate departure from Sudan. Insisting that he had no intention of leaving, Arman described the death sentence hovering over him as “a political ruling par excellence” (Radio Dabanga, May 30, 2019).

Conclusion

The TMC’s warning to Yasir Arman demonstrates that the military council is even less ready to work with the armed opposition than with civilian protest leaders. The plight of the non-Arab POWs who fought for years to remove Bashir is indicative of the enduring elitism of northern Sudan’s Arab population, especially the Nile-based Danagla, Sha’iqiya and Ja’alin tribes. The little-discussed truth of Sudan’s revolution is that many of the pro-democracy demonstrators in Khartoum, like the military, have little interest in the welfare of non-Arab rebels who fought and suffered for years to remove Bashir and the ruling clique. Their plight formed part of Yasir Arman’s agenda for talks in Khartoum, but the TMC’s continuing refusal to even meet with the armed opposition leader suggests the military has little intention of abandoning its anti-insurgency campaigns in Sudan, which provide it with wealth and power at the expense of Sudan’s political and economic development.

Note

[1] See: “Musa Hilal: Darfur’s Most Wanted Man Loses Game of Dare with Khartoum… For Now,” AIS Special Report, December 12, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4096