Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report, July 20, 2019

Deep in the desert of Libya’s southwestern Fezzan region is the ancient town of Murzuq, a small commercial hub and oasis in the midst of some of the world’s most difficult and energy-sapping terrain. At the moment, it is the scene of a bitter struggle between local fighters of the indigenous black Tubu group and Libyan National Army (LNA) forces led by “Field Marshal” Khalifa Haftar, a former CIA asset now tentatively backed by Russia. Haftar also enjoys military support from Egypt, France and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in his campaign to conquer Libya.

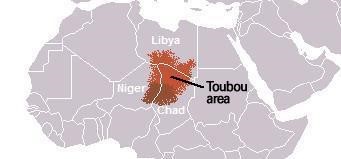

Murzuq is not an easy place to live – the town experiences extreme heat year round. In the current summer months, Murzuq has an average daily temperature of over 90º F and daily highs over 100º F. In the 19th century, Murzuq was infamous for a virulent and usually fatal fever that felled Ottoman authorities and European visitors alike. Despite this, Murzuq remains home to many members of the indigenous Tubu ethnic group, famous for their physical endurance and martial skills. The Tubu, ranging through southern Libya, eastern Niger and northern Chad, share a common culture but are split by dialect into two groups, the northern Teda and the southern Daza.

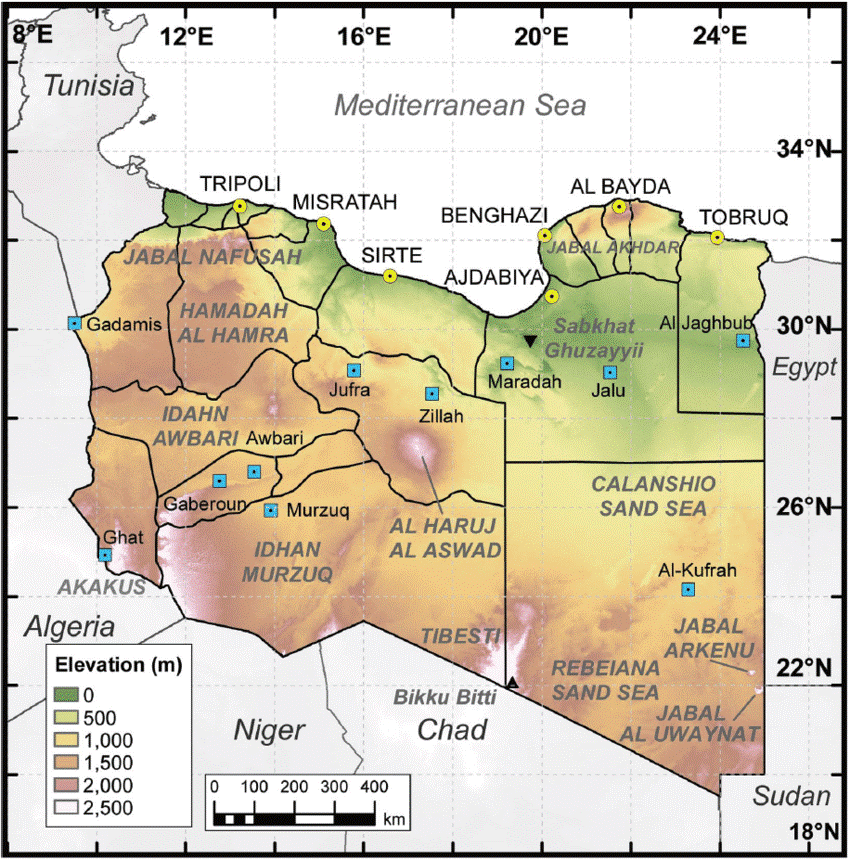

Murzuq at 14º E and 26º N.(Atlas of Reptiles of Libya)

Murzuq at 14º E and 26º N.(Atlas of Reptiles of Libya)

Many Libyan Tubu have complained of “ethnic cleansing” by Libya’s Arabs and Arab/Berber tribes since the 2011 Libyan revolution, even though most Tubu sided with the revolutionaries against Qaddafi, who had revoked their citizenship and treated them as foreign interlopers despite their historical presence in southern Libya long before records were kept. In this, they stood apart from their Saharan neighbors and occasional rivals, the Tuareg, most of whom backed Qaddafi and played an important role in the dictator’s army.

Until recently, the non-Arab Tubu and Tuareg had observed a century-old non-aggression treaty, but the Tubu have endured recurring clashes with Arab tribes, most notably (but not exclusively) the Awlad Sulayman in Fezzan and the Zuwaya in the Kufra region of southern Cyrenaïca (eastern Libya, Haftar’s power-base). The overthrow of the Qaddafi regime and the subsequent failure to replace it with a unified government has exacerbated these ethnic tensions and revived the Arab canard that the Tubu are foreigners from Chad and Niger in need of expulsion.

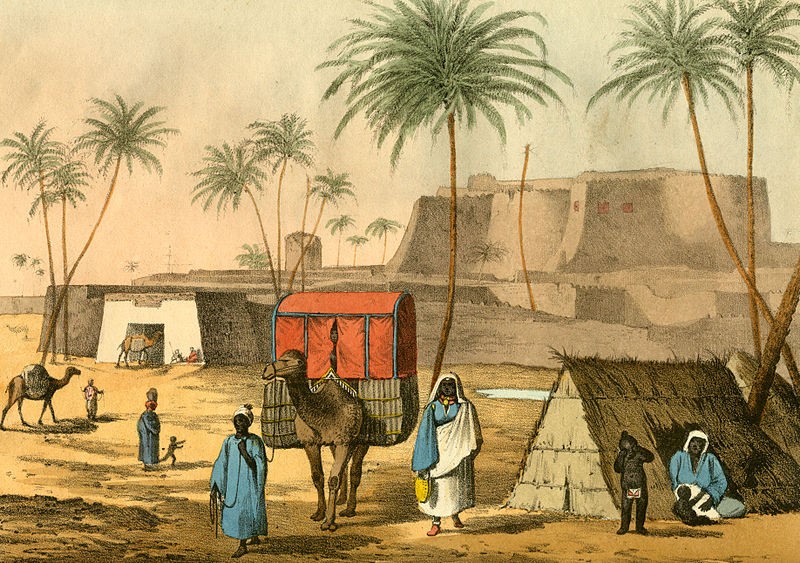

Murzuq is a strategically located city in the sparsely inhabited Fezzan, some 144 km south of the regional capital of Sabha, which has also been the site of battles between Tubu and Arab Awlad Sulayman factions since 2011. Unlike Sabha, with its Tubu minority, Murzuq is largely Tubu. Like many of the southern settlements centered on rare oases, Murzuq is home to an impressive Ottoman-era castle later used by Italian colonial garrisons.

Located on a route between nearly impassable and water-less sand seas, control of Murzuq is important to the control of Libya’s most productive oil fields as well as offering dominance of several trans-Saharan trade routes that must past through here. Italian-occupied Murzuq was the target of one of the Second World War’s most daring desert raids, with British and New Zealanders of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) joining Free French desert fighters to cross hundreds of miles of barren desert to launch a surprise attack on the Italian outpost. Italian losses were heavy, the aerodrome and its bombers shattered and the fort badly damaged by mortar fire before the raiders withdrew. General Leclerc’s Free French returned to claim Murzuq in January 1943, completing the Allied conquest of the Fezzan.

Haftar’s Offensive in Fezzan

“Field Marshal” Khalifa Haftar leads the Libyan National Army (LNA), a loose coalition of militias ostensibly operating on behalf of one of Libya’s two competing government, the Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR). In practice, the LNA serves as a vehicle for the advancement of Haftar’s personal agenda, which includes taking control of Libya and establishing a family dynasty. Though most Tubu support the rival and UN-recognized Presidency Council/Government of National Accord (PC/GNA, based in Tripoli), there are also Tubu representative in the HoR. Tubu support for the PC/GNA is not firm, as the community regularly complains of a lack of government support and services in the south. The region as a whole continues to suffer from economic decline, widespread unemployment, inadequate infrastructure and soaring crime rates. Smuggling and human trafficking present attractive alternatives to grinding poverty.

Haftar began his offensive in southwestern Libya in January 2019, with the cited objectives of securing the region and “protecting residents from terrorists and armed groups” (Libya Observer, January 19, 2019). More importantly, for Haftar at least, was the necessity of securing the volatile and loosely governed Fezzan before advancing on Tripoli to complete Haftar’s conquest of Libya and destruction of the UN-recognized government before elections scheduled for December.

Before launching the offensive, Haftar formed a southern battle group in October 2018 composed of the 10th Infantry Brigade, the Subul al-Salam Battalion (Kufra-based Salafists, mostly Zuwaya Arabs), and the 116th, 177th and 181st Battalions (Libya Herald, October 24, 2018).

As LNA forces advanced on southwestern Libya, anti-Haftar Tubu fighters responded by creating the “South Protection Force” (SPF). In its first statement, the SPF condemned the LNA’s “military aggression” and called for an investigation into the LNA’s use of Sudanese mercenaries (Libya Herald, February 7, 2019). Both rival governments have resorted to using rebels from Darfur and Chad (many of the latter being Chadian Tubu) who have taken refuge in southern Libya after being forced out of their home bases by government military operations. Haftar and the LNA typically refer to Libyan Tubu as Chadian rebels in need of expulsion from southern Libya.

Clashes against Tubu fighters in Ghadduwah oasis (lying roughly halfway between Murzuq and Sabha) began on February 1, leaving 14 killed and 64 wounded (Libya Observer, February 2, 2019). Fighting continued through the week as the LNA claimed it was clearing Chadian rebel movements from the area. However, observers and local Tubu claimed that the oasis’s Tubu residents were the real target, leading to a series of resignations of Tubu HoR members and officials citing racial persecution (Libya Observer, February 3; Libya Observer, February 6, 2019). LNA spokesman General Ahmad al-Mismari had a different view of the military operations, insisting “Our Tubu brothers fight with us” (AFP, February 6, 2019). The oasis was eventually turned into a base for regional LNA operations.

Ottoman-Era Castle in Murzuk, 1821 (George Francis Lyon)

Ottoman-Era Castle in Murzuk, 1821 (George Francis Lyon)

Warplanes attached to the LNA (likely UAE in origin) carried out an airstrike on Murzuk on February 3, killing 7 and wounding 22. LNA spokesmen claimed the strike had targeted a gathering of the “Chadian opposition” (Libyan Express, February 4, 2019). On the same day, French warplanes attacked a column of 40 pickup trucks carrying Chadian rebels across the border back into northern Chad. According to the LNA, these fighters were fleeing the LNA offensive (AFP, February 6, 2019). [1]

Local Tubu were alarmed that much of the LNA force advancing on Murzuq was composed of Tubu rivals such as the Brigade 128 (Awlad Sulayman), led by Major Hassan Matoug al-Zadma, and the Deterrence Brigade led by Masoud al-Jadi (Libya Observer, February 2, 2019). Also figuring prominently in the LNA force were Darfurian mercenaries from the rebel Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) who had been driven out of Darfur by the operations of Sudan’s military and the notorious Rapid Support Forces (RSF) of General Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti.” [2] Murzuq HoR member Rahma Abu Bakr described the situation in Murzuq as “tragic” on February 4, saying the town was besieged by “tribal forces” (Libyan al-Ahrar TV [Doha], February 4, 2019).

By February 5, the LNA’s Tariq bin Zayid Brigade (Madkhali Salafists) was involved in clashes inside Murzuq as it prepared to mount an offensive on the Umm al-Aranib region, northeast of Murzuq. [3] At the same time, the LNA’s 141st Brigade was cutting off exit and entry points for armed groups within the town (Libya 218 TV [Amman], February 5, 2019). Stocks of fuel, food and medical supplies reached critically low levels under the LNA blockade. Tubu reluctance to negotiate with an LNA command composed of their tribal enemies and Sudanese mercenaries was stiffened by social media posts from individual members of the LNA force threatening the Tubu with genocide and expulsion from their traditional lands (Libya Observer, February 3, 2019).

Murzuq’s Old Mosque (foreground) and Ottoman-Era Castle as they appear today.

Murzuq’s Old Mosque (foreground) and Ottoman-Era Castle as they appear today.

On February 8, the LNA announced it had carried out “violent and painful” airstrikes on three groups of “Chadians and their allies” near Murzuk (Defense Post, February 8, 2019). The next day, LNA aircraft struck the runway at nearby al-Fil oilfield just as a Libyan Airlines plane was about to leave for Tripoli with a load of sick and wounded people in need of treatment. Tripoli’s Presidential Council (PC) described the incident as “a terrorist act and a crime against humanity” and an attempt to deprive Libyans of their oil resources (Libya Observer, February 9, 2019).

Struggle for the Oilfields

A century-old peace agreement between the Tubu and the Tuareg that defined tribal territories did not survive the political violence that followed the 2011 revolution, with large clashes breaking out in the Tuareg-dominated city of Ubari, roughly 80 miles northwest of Murzuq. A 2015 peace treaty brokered by Qatar that also included the Arab Awlad Sulayman was short-lived, though it was replaced by another agreement signed in Rome in 2017. However, Haftar’s intrusion into Fezzan and his alliance with the Awlad Sulayman brought an effective end to that treaty as well.

A chief objective for Haftar’s LNA in the south was control of the Sharara oilfield, Libya’s largest, capable of producing 315,000 barrels per day. Security at the facility was handled since 2017 by Tuareg fighters of Brigade 30, led by Ahmad Allal. The brigade initially repulsed attempts by the local LNA affiliated 177th Brigade (mostly Hasawna Arabs, led by Colonel Khalifa al-Seghair al-Hasnawi) to take over the Sharara oilfield (Libya Herald, February 7, 2019).

In response to the incursion by LNA fighters, the GNA commander for the Fezzan, Tuareg General Ali Kanna Sulayman, attempted to build a military alliance of Tubu and Tuareg minorities, most of whom shared similar grievances with the government and animosity towards Haftar and the Arab gunmen who followed him. [4 However, Kanna failed to bring Brigade 30 onside amidst pressure from Tuareg elders to abandon the facility in order to avoid pitting one Tuareg group against another. Kanna left for al-Fil and by February 12 the LNA-aligned Tuareg Brigade 173 began to move into the main facility after negotiating with armed protesters who had held parts of the oilfield since December 2018, forcing the National Oil Corporation (NOC) to declare a state of force majeure at the facility (Middle East Monitor, February 12, 2019; Middle East Eye, February 10, 2019).

Production resumed under LNA occupation, but by July 14, protesters again threatened to take over the facility as well as al-Fil oilfield, which has been closed by a strike over salaries since February (Libya Observer, July 14, 2019; AFP, July 15, 2019). Protesters frequently take over oil and water pumping facilities (part of Libya’s vast “Man-Made River” project) to call attention to days-long power outages and shortages of fuel and water in the south that persist despite the south being Libya’s main source of wealth and resources.

Battle for Murzuq

The LNA moved on Murzuq in early February, beginning with airstrikes and a fuel blockade. Once Sharara was secured, Awlad Sulayman fighters began to enter Murzuq from the east on February 20, though they met stiff resistance from Tubu fighters of the South Protection Force (Libya Observer, February 20, 2019).The assault on Murzuq followed failed negotiations between residents and the LNA, represented by LNA Special Forces commander Wanis Bukhamada.

Gunmen believed to belong to the LNA broke into the home of local security director Ibrahim Muhammad Kari on February 20, murdering the unarmed officer and stealing his safe before torching his home (Libya Observer, February 21, 2019).

The LNA claimed to have secured Murzuq on February 21, but other reports suggested the Tubu, aided by Chadian mercenaries, had in fact repulsed Haftar’s troops in ongoing fighting (Libya Herald, February 21, 2019). Within a few days, however, the LNA consolidated its control of Murzuq. By February 26, Tubu fighters were withdrawing to the south and the LNA announced it had “liberated Murzuq from Chadian gangs” (Libya Observer, February 24, 2019). The occupation permitted the LNA to take over the nearby al-Fil oilfield the following day.

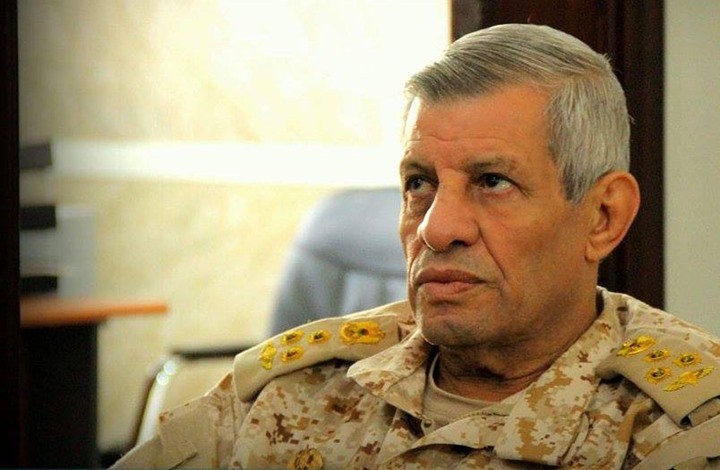

LNA Brigadier ‘Abd al-Salim al-Hassi

LNA Brigadier ‘Abd al-Salim al-Hassi

Murzuq was quickly engulfed in looting, arson and extra-judicial killings. As many as 104 cars belonging to Tubu residents were stolen and 90 houses torched while activists and community leaders were hunted down by LNA gunmen. Even the home of local Tubu HoR representative Muhammad Lino as well as those of his brother and father were burned down, allegedly on the orders of the LNA’s commander of military operations in the west, Brigadier General ‘Abd al-Salim al-Hassi (Libya Observer, February 24, 2019).

One Murzuq resident complained that Libyan TV didn’t “say the truth, they just show the LNA celebrating and saying ‘we have liberated Murzuq and there is now security and freedom.’ But it’s not true. We are not okay and we do not have freedom” (Middle East Eye, February 26, 2019). There were soon numerous complaints from Tubu leaders and politicians that Haftar’s LNA was conducting “ethnic cleansing” and “ethnic war” (AFP, February 6, 2019; Libya Observer, February 23, 2019).

Much of the looting and arson was blamed on mercenaries from Darfur employed by Haftar’s LNA. One of the occupying brigades, the 128th (commanded by Awlad Sulayman Major Hassan Matoug al-Zadma) was composed of members of Kufra’s Zuwaya tribe and members of Fezzan’s Awlad Sulayman, both traditional enemies of the Tubu. Observers recorded video footage showing fighters from Darfur’s rebel Sudan Liberation Army – Minni Minawi (SLA-MM, mostly Zaghawa) operating as mercenaries tied to the LNA’s Brigade 128 (Middle East Eye, February 26, 2019; Middle East Eye, February 14, 2019; Libya Herald, February 7, 2019). [5]

Evacuation and Return

The LNA began a surprise evacuation of Murzuq late in the day on March 5, redeploying to Sabha after heavy clashes in Murzuq both before and during the evacuation that left four Tubu tribesmen dead (Libya Observer, March 6, 2019, Libyan Express, March 6, 2019).

As residents attempted to restore normalcy after the LNA occupation, Representative Muhammad Lino noted a lack of support from Tripoli’s PC/GNA and demanded to know whether there was coordination between allegedly rival political formations to “exterminate” the Tubu. The representative also noted that the HoR had denounced the March 15 mosque attack in New Zealand but had nothing to say about the death of Muslims in Murzuq (Libya Observer, March 26, 2019).

Murzuq residents were dismayed when the LNA returned early this month, allegedly in pursuit of Chadian rebels and Islamic State terrorists whom they blamed for the armed resistance to the LNA’s return. Murzuq’s Security Directorate issued a statement denying the presence of Chadian fighters or Islamic State forces in Murzuq, insisting only Tubu residents of the town were involved in the battle against Haftar’s invasion force (Libya Observer, July 9, 2019).

As the LNA re-occupied Murzuq, deadly clashes broke out between Tubu residents and members of the local al-Ahali community (Arabized black Libyans descended from slaves or economic migrants) (Anadolu Agency, July 11, 2019). On July 10, the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) expressed concern over the human cost of Tubu clashes with the LNA occupiers (Libyan Observer, July 10, 2019).

Conclusion

It seems increasingly clear that Khalifa Haftar and his Arab allies in the LNA are intent on reversing any gains Libya’s southern minorities may have made since the 2011 revolution. Both the Tubu and the Tuareg were used and abused by the Qaddafi regime according to the “Supreme Guide’s” whims and needs. Both were denied their ethnic identity, the Berber Tuareg characterized in Qaddafi’s mind as “southern Arabs” and the indigenous Tubu denied all rights as Libyan citizens.

Some Tubu support the LNA’s campaign against Chadian rebels and mercenaries, but are dismayed by the LNA’s indifference to their support and their continuing identification of all indigenous Tubu as non-Libyan foreigners, an attitude fostered by Arab supremacists during and after the Qaddafi regime.

Like the Tuareg, Libya’s Tubu population is determined not to be driven out from their harsh ancestral homeland where they have roamed for thousands of years. The vast spaces of the Libyan interior, its brutal climate and harsh topography make deployment there highly unpopular amongst the coastal Arabs who contribute the vast majority of Haftar’s LNA. Securing Libya’s southern borders, oil resources and water supply will require the cooperation of Libya’s southern minorities, not their elimination. A new Libyan state cannot be built on a foundation of ethnic cleansing, identity denial and Qaddafi-era Arab supremacism.

Notes

- For the Chadian rebels and their efforts to return to Chad, see: “War in the Tibesti Mountains – Libyan-Based Rebels Return to Chad,” AIS Special Report, November 12, 2018, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4308

- For Hemetti and the RSF, see: “Snatching the Sudanese Revolution: A Profile of General Muhammad Hamdan Daglo ‘Hemetti’,” Militant Leadership Monitor, June 30, 2019, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4455

- For the role of the Madkhali Salafists in the Libyan conflict, see: “Radical Loyalty and the Libyan Crisis: A Profile of Salafist Shaykh Rabi’ bin Hadi al-Madkhali,” Militant Leadership Monitor, January 19, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3840

- For General Ali Kanna, see “General Ali Kanna Sulayman and Libya’s Qaddafist Revival,” AIS Special Report, August 8, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3999

- For Minni Minawi, see: “The Unlikely Rebel: A Profile of Darfur’s Zaghawa Rebel Leader Minni Minawi,” Militant Leadership Monitor, December 8, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4088