CTC Sentinel (Volume 10, Issue 2)

CTC Sentinel (Volume 10, Issue 2)

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point

February 22, 2017

Andrew McGregor (AIS)

Abstract: Alongside the Islamist struggle to reshape society in the Sahel through violent means is a second, relatively unnoticed but equally deadly conflict with the dangerous potential of merging with jihadi efforts. At a time when resources such as land and water are diminishing in the Sahel, semi-nomadic Muslim herders of the widespread Fulani ethnic group are increasingly turning to violence against settled Christian communities to preserve their herds and their way of life. Claims of “genocide” and “forced Islamization” have become common in the region. What is primarily an economic struggle has already taken on an ethnic and religious character in Mali. If Nigeria follows the same path, it is possible that a new civil war could erupt with devastating consequences for all of West Africa.

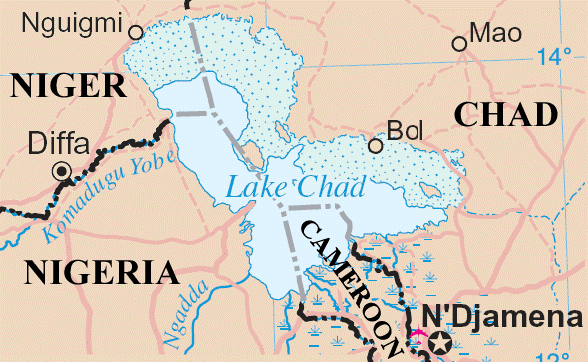

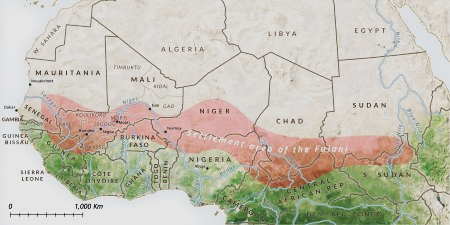

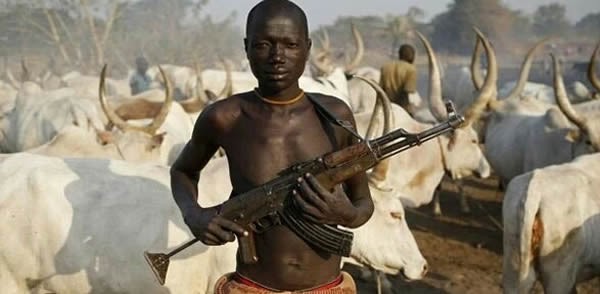

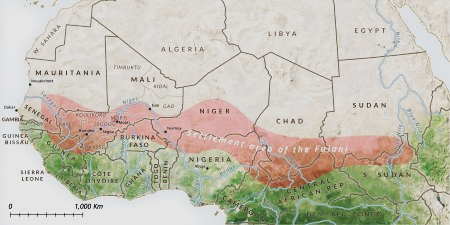

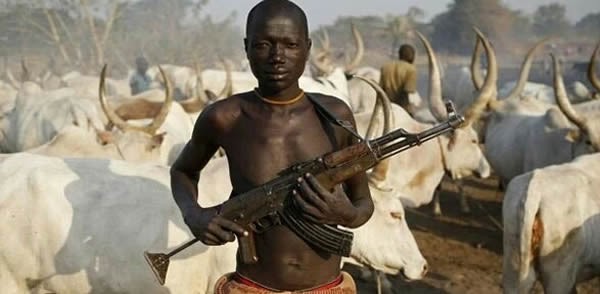

The Fulani,a an estimated 25 million people, range across 21 African countries from Mauritania’s Atlantic coast to the Red Sea coast in Sudan, though their greatest concentration is found in West Africa’s Sahel region.b The Fulani speak a common language (known as Fulfulde or Pulaar) but, due to their wide geographical range, are known by several other names in their host communities, including Fulbe, Fula, Peul, Peulh, and Fellata. Virtually all are Muslim. Roughly a third of the Fulani continue to follow a traditional semi-nomadic, cattle-rearing lifestyle that increasingly brings them into conflict with settled agriculturalists at a time of increased pressure on resources such as pastureland and water. They are typically armed to protect their herds from rustlers, wild animals, and other threats, and in recent years, the ubiquitous AK-47 has replaced the more common machete as the weapon of choice.

The Fulani in the Sahel (Rowan Technology)

The Fulani in the Sahel (Rowan Technology)

The Fulani began building states in the 18th century by mounting jihads against non-Islamic rulers in existing states in the Guinea-Senegal region. A Fulani Islamic scholar, ‘Uthman Dan Fodio, recruited Fulani nomads into a jihad that overthrew the Muslim Hausa Amirs of the Sahel and attacked the non-Muslim tribes of the region in the first decade of the 19th century, forming a new kingdom in the process—the Sokoto Caliphate. Following Dan Fodio’s Islamic revolution, a whole series of new Islamic Emirates emerged in the Sahel under the Sokoto Caliphate, which fell to the British in 1903. There are accusations within Nigeria’s legislatures that the current Fulani-associated violence is simply the continuation of Dan Fodio’s jihad, an attempt to complete the Islamization of Nigeria’s middle belt and eventually its oil-rich south.1

Nomadic patterns and a significant degree of cultural variation due to their broad range in Africa have worked against the development of any central leadership among the Fulani. Traditional Fulani regard any occupation other than herding as socially inferior, though millions now pursue a wide range of occupations in West Africa’s urban centers.

Herdsmen vs. Farmers

Traditionally, Fulani herders would bring their cattle south during the post-harvest period to feed on crop residues and fertilize the land. Recently, however, environmental pressures related to climate change and growing competition for limited resources such as water and grazing land are driving herders and their cattle into agricultural areas year round, where they destroy crops.2 More importantly, the herders are now entering regions they have never traveled through before. The growth of agro-pastoralism, where farmers maintain their own cattle, and the expansion of farms into the traditional corridors used by the herders have contributed to the problem. The resulting violence is equal in both number and ferocity to that inflicted by Boko Haram’s insurgency3 c but has attracted little attention beyond the Sahel, in part because it is treated as a local issue.

Confrontations over damaged crops are typically followed by armed herders responding to the farmers’ anger with violence, inevitably leading to reprisal attacks on herding camps by farming communities. Traditional conflict resolution systems involving compensation and mediation have broken down, partly because new waves of herdsmen have no ties to local communities.d The Fulani, in turn, accuse their host communities of cattle rustling (theft) and therefore regard punitive violence against these communities as just and appropriate. The Fulani herders complain that they are otherwise faced with the choice of returning to lands that cannot sustain them or abandoning their lifestyle by selling their cattle and moving to the cities.4

With little protection offered by state security services against the incessant violence, many farmers have begun abandoning their plots to seek safety elsewhere, leading to food shortages, depopulation of fertile land, and further damage to an already fragile economy. Some see no future in negotiations: “We are calling on the state government to evacuate [the herders] from our land because they are not friendly; they are very harmful to us. We are not ready to bargain with them to prolong their stay here.”5 Others have registered puzzlement that relations with “people who have always been around” (i.e. the herders) could have deteriorated so dramatically.6

Nigeria’s Military Option

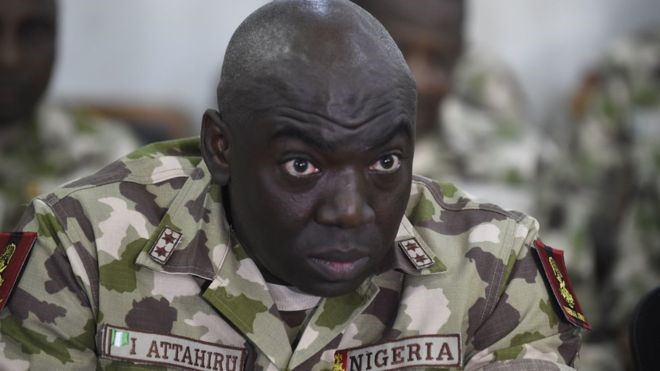

In late October 2016, Nigerian Defense Ministry spokesman Brigadier General Rabe Abubakar declared Boko Haram “100% defeated” and announced the launch of “Operation Accord,” a military campaign to “take care of the nuisance of the Fulani herdsmen once and for all.” 7 e Unfortunately, no mention was made of what kind of tactics would be employed to prevent ethnic nationalism and religious radicalism from further taking hold in the Fulani community.

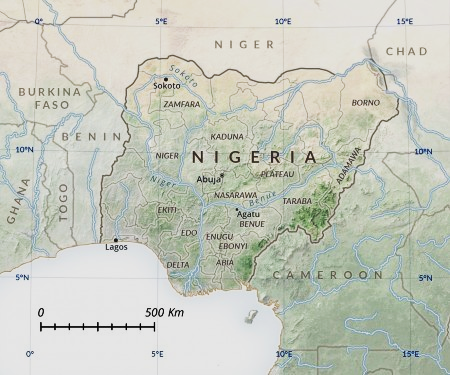

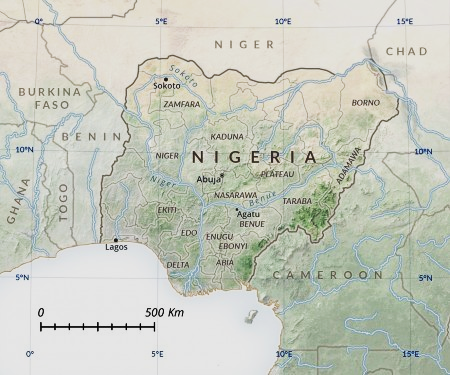

Nigeria (Rowan Technology)

Nigeria (Rowan Technology)

A common complaint from victims of Fulani violence is that help from security services rarely materializes despite their assurances that security is a top priority. This has led to the formation of anti-Fulani vigilante groups (some inspired by Borno State’s anti-Boko Haram “Civilian JTF”) that have few means and little inclination to sort out “bad” herders from “good.” Existing vigilante groups tend to have poor coordination with police services, perhaps deliberately in some cases due to suspicion that the security services sympathize with the herdsmen.8 Earlier this year, the United Nations stated advance warnings of the April 2016 attack in Enugu State that killed 40 people had been ignored and noted that perpetrators of earlier attacks appeared to enjoy “complete immunity,” which encouraged threatened communities to “take justice into their own hands.”f

In Zamfara State, rural communities have complained of Fulani herdsmen committing murder, gang-rapes, destruction of property, and massive thefts of livestock while security services do nothing. Reprisals are now organized by a Hausa vigilante group named Yan Sakai. Though banned by the government, Yan Sakai continues to operate, escalating the violence through illegal arrests and summary executions.9

Delta State’s former commissioner of police Ikechukwu Aduba expressed exasperation with the growing crisis: “The problem is how do we contain [the herdsmen], especially with their peculiar mode of operation? The way these people operate is amazing. They will strike within five and six minutes and disappear… there is no way the police can be everywhere at the same time.”10 Difficult terrain and poor communications complicate the matter, but the continued inability of the state to provide a reasonable degree of security damages public trust in authority and encourages an armed response in previously peaceful communities.

One claim that has gained traction among leaders of the Igbo (a large ethnic group with an estimated population of 30 million people in southern Nigeria) is that the country’s president, Muhammadu Buhari (a Fulani), is pursuing the Islamization of Nigeria by allowing Fulani herdsmen to murder Christians.11 These claims were rejected on October 10, 2016, by the Sultan of Sokoto, Muhammadu Sa’ad Abubakar III, a Fulani and one of Nigeria’s leading Islamic authorities: “The problem with herdsmen and farmers is purely about economy. The herdsman wants food for his cattle; the farmer wants his farm produce to feed his family.”12 There have been calls for the sultan to make a personal intervention, appealing to the Fulani’s respect for “true leaders and their traditional institutions.”13 The sultan, however, like the cattle associations representing the herders, claims that those involved in the violence are “foreign terrorists … the Nigerian herdsmen are very peace-loving and law-abiding.”14

Solutions?

Herders cannot simply be outlawed. Despite the violence, they continue to supply the Sahel’s markets with meat. Grazing reserves have been proposed as a solution, but since these are seen as a government transfer of land to commercial livestock operations, they are unpopular. Fulani herders often object that such reserves are inaccessible or already in use by other herders. In May 2016, some 350 federal and state legislators declared they would resist any attempt by the federal government to take land by force for use as grazing reserves. Others have argued that ranching on fenced private lands (preferably in the north, where ethnic and religious tensions are diminished) is the only solution for Nigeria, where questions of land ownership remain politically charged.15 Nonetheless, 10 Nigerian states moved ahead in August 2016 with allocating grazing lands to the herdsmen.16

Ranching would improve yields of meat and milk, both of which suffer from nomadic grazing. (Most of Nigeria’s milk is now imported from the Netherlands.) According to House of Representatives minority leader Leo Ogor, “The solution lies in coming up with legislation that will criminalise grazing outside the ranches.”17 Governor of Benue State Samuel Ortom has said, “If we can copy the presidential system from America, why can’t we copy ranching? But, you see, it is a gradual process and cannot be done overnight.”18

Street Violence in South Kaduna

Christians in Nigeria’s Kaduna State complaining of daily kidnappings, killings, and rapes committed by herders have described the large Ladugga grazing reserve as an “incubator” for “all sorts of criminals that are responsible for the misfortune that has come to stay with us.”19 An editorial in a major Nigerian daily described the reserves as “a decoy” for Fulani herders to overrun and seize land from “unsuspecting natives.” “It is incomprehensible how anyone expects the entire country to have grazing reserves carved out for Fulani herdsmen … what else is the motive behind this adventure if it is not to grab land and have strategic power?”20

Three federal bills trying to establish grazing reserves and control of herd movement were dropped by Nigeria’s senate last November after it was ruled such legislation must be enacted at the state level. This will likely result in a patchwork of efforts, however, to solve a problem that is, by its very nature, unconfined by state or national borders.21

In Ghana, joint military/police task-forces have been deployed to evict Fulani herdsmen from regions affected by communal violence.22 Many of the herdsmen are from Burkina Faso where pastureland has receded. To deal with what has been described as “a national security issue due to the crimes associated with the activities of the nomads,” Ghanaian President John Dramani Mahama announced that veterinary services and 10,000 hectares of land would be provided to the herdsmen to discourage violent clashes with farmers.23 The measure falls short of the ranching laws that have been promised since 2012 but have yet to be implemented.24

Dr. Joachim Ezeji, an Abuja, Nigeria-based water management expert, attributes the violence to poor water management practices in Nigeria that are “not robust enough to cope with the impacts of climate change,” suggesting soil restoration, reforestation, and the expansion of terrace-farming could aid the currently unproductive, sloping land.25

Nigeria: Economic Struggle or Religious Conquest?

In early 2016, the streets of Abuja, Nigeria’s capital, began filling with Fulani herders and their livestock, snarling traffic and prompting fights between herders and beleaguered motorists. A ban on grazing in the federal capital had been widely ignored, and in October 2016, authorities began arresting herders and impounding their livestock.26 The local government has obtained over 33,000 hectares of land as an alternative to grazing in the streets of the capital.27

The Nigerian capital, however, has yet to experience the herdsmen-related violence that continues to afflict the following regions:

Northwest (primarily Muslim): Kaduna and Zamfara States

Middle Belt (ethnically heterogeneous and religiously mixed): Nasarawa, Taraba, Benue, Plateau, Adamawa, and Niger States

South (primarily Christian and Animist): Ebonyi, Abia, Edo, Delta, and Enugu States

At times, Fulani gunmen have shown no fear of attacking senior officials. On his way to visit a displaced persons’ camp in April 2014, former Benue governor Gabriel Suswam’s convoy was ambushed by suspected Fulani herders who engaged the governor’s security detail in a one-hour gun-battle. Afterwards, Suswam told the IDPs:

This is beyond the herdsmen; this is real war … so, if the security agents, especially the military, cannot provide security for us, we will defend ourselves … these Fulani are not like the real Fulani we used to know. Please return to your homes and defend your land; do not allow anybody to make you slaves in your homeland.28

The Ekiti State’s Yorubag governor, Ayodele Fayose, has implemented laws designed to control the movements of the Fulani herdsmen, much to their displeasure. A statement from the Mayetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association (MACBAN, a national group representing the interests of Fulani herders) suggesting that the new laws could “develop into [an] unquenchable inferno … capable of creating uncontrollable scenarios” was interpreted by local Yoruba as “a terror threat.”29 The governor described the federal government’s failure to arrest those responsible for the MACBAN statement as proof of a plot “to provide tacit support” to the herdsmen.30 With clashes threatening to deteriorate into ethnic warfare, Fayose called on Ekiti citizens to defend their land against “these Philistines” whose character is marked by “extremism, violence, bloodshed, and destruction.”31

Some senior Christian clergy have alleged the influx of Muslim herders is a scheme by hard-pressed Boko Haram leaders “to deliberately populate areas with Muslims and, by the sheer weight of superior numbers, influence political decision-making.”32 After herders killed 20 people and burned the community of Gogogodo (Kaduna State) on October 15, 2016, a local pastor described the incident in religious terms. “This is a jihad. It is an Islamic holy war against Christians in the southern part of Kaduna state.” Another said that like Boko Haram, the Fulani had a clear agenda “to wipe out the Christian presence and take over the land.”33 As many as 14 Fulani were hacked to death in retaliatory attacks.34

In late February 2016, alleged herders reportedly massacred over 300 Idoma Christians in Agatu (Benue State). A retaliatory attack on a Fulani camp across the border in Nasarawa State on April 30 killed 20 herdsmen and 83 cows.35 After the killings, Nigeria’s senate moved a motion suggesting attacks attributed to Fulani herdsmen were actually “a change in tactics” by Boko Haram. This view was roundly rejected by Benue State representatives in the House of Representatives, who castigated the president for his silence on the attacks. According to the leader of the Benue caucus, the incidents were an “unfolding genocide in Benue State by Fulani herdsmen, a genocide that, typical of the Nigerian state, has been downplayed or ignored until it spirals out of control.”36

However, it is not only Nigeria’s farming communities that complain of “genocide.” For Nigeria’s Muslim Rights Concern (MURIC), attacks on “innocent Fulani” by vigilantes, rustlers, and security forces constitute an effort to eliminate Islam in Nigeria:

The Nigerian Muslim community as a stakeholder in nation-building is also aware of the symbiotic relationship between the Fulani and the religion of Islam and, by extension, the Muslim Ummah of Nigeria. Any hostile act against the Fulani is therefore an indirect attack on Muslims. Genocide aimed at the Fulani is indubitably mass killing of Muslims. It is war against Islam.37

Fulani Herdsman (Judith Caleb)

Fulani Herdsman (Judith Caleb)

There were further attacks in Benue allegedly by Fulani herdsmen in late April 2016. A local Fulani ardo (community leader), Boderi Adamu, said that the attackers were not Fulani—he “heard people say they were foreigners”—but insisted that the Nigerian constitution provided free movement for all citizens within its borders, “so they cannot continue to stop us from finding pastures for our cows.”38 However, as one Nigerian commentator observed, while “the constitution grants free movement to all its citizens, it does not grant free movement to hordes of animals with those citizens … cows cannot overrun a whole country. It is unacceptable.”39 Despite a January 6, 2017, agreement between Fulani herdsmen and the majority Christian Agatu community in Benue State, violence erupted again on January 24 with 13 villagers and two herdsmen killed during an attack by Fulani herders.40

Ties to Boko Haram?

It is possible that some of those participating in the attacks on farming communities in Nigeria are former members of Boko Haram who trade in violence, but coordination with the group itself is unlikely. Boko Haram is dominated by Kanuri rather than Fulani, and the rights of cattle-herders have not figured prominently in the group’s Islamist agenda.

There are other differences from Nigeria’s Boko Haram rebellion:

- Though many Boko Haram members are ethnic Kanuri, the Boko Haram insurrection never took on an ethnic character, and the movement’s leadership has never claimed one.

- Boko Haram’s identity and aims center on religion. The Fulani herders’ main concern is with access to grazing land, although they are susceptible to religious agitation.

- Boko Haram’s enemy (despite leader Abu Musab al-Barnawi’s recent calls for attacks on Christians) has always been the state. Armed Fulani groups generally avoid confrontations with the state.

- Like most insurgent movements, Boko Haram has a central leadership that is generally identifiable despite the movement’s best efforts to keep details murky. There is no guiding individual or committee behind the violence associated with the Fulani herders.

Transition to Jihad: The Case of Mali

A significant concern is posed by the possibility that Nigeria might follow the pattern of Mali. There, young Fulani herdsmen have been recruited into jihadi movements, a break from the Fulani community’s traditional support of the Bamako government as a balance to Tuareg and Arab power in northern Mali.41

Unlike other parts of the Sahel, there is a long tradition of Fulani “self-defense” militias in northern and central Mali. Known as Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso, these groups were generally pro-government in orientation but clashed repeatedly since 1990 with both separatist and loyalist Tuareg groups over land and access to water.

Some Fulani from central Mali and northern Niger joined the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA) during the Islamist takeover of northern Mali in 2012.42 Since France’s Operation Serval in 2013 expelled most of the Islamists from the region, Fulani in the Mopti and Segou regions have experienced retaliatory violence and abuse from both the Malian military (including torture and summary executions) and Fulani jihadis who want to deter their brethren from cooperating with the Malian state, U.N. peacekeepers, or French troops.43 The national army, the Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMA), are allegedly replicating the human rights abuses (arbitrary detention, torture, extrajudicial killings) that helped inspire rebellion in northern Mali.44 According to one Fulani chief, “Our people don’t associate the state with security and services, but rather with predatory behavior and negligence.”45

After Operation Serval, many of the Fulani jihadis drifted into the Front de libération du Macina (FLM, aka Katiba Macina or Ansar al-Din Macina), a largely Fulani jihadi movement led by salafi preacher and Malian national Hamadoun Koufa. Based in the Mopti region in central Mali, the group takes its name from a 19th-century Fulani state. The Islamists spur recruitment by reminding young Fulanis that their traditional leadership has been unable to defend their people from Tuareg attacks or cattle-rustling, according to the author’s research. The movement became formally allied with Ansar al-Din on May 19, 2016, but split off from Iyad Ag Ghali’s mostly Tuareg jihadi movement in early 2017 due to ethnic tensions, Hamadoun Koufa’s dalliance with the rival Islamic State movement, and the FLM’s failure to provide military support for Ansar al-Din.46 Reports suggest that FLM leader Hamadoun Koufa has been engaged in discussions with the leader of the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui, regarding the creation of a new Fulani caliphate with Islamic State support.47

An unknown number of Fulani appear to have joined Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s al-Murabitun movement. The group claimed that its January 17, 2017, suicide car-bomb attack that killed 77 members of the Malian Army and the Coordination of Azawad Movements coalition was carried out by a Fulani fighter, Abd al-Hadi al-Fulani.48 The attack followed similar suicide attacks by Fulani jihadis. Though there was some confusion created by rival claims of responsibility for the November 20, 2015, attack on Bamako’s Radisson Blu hotel from al-Murabitun and the FLM (allegedly in concert with Ansar al-Din), al-Murabitun maintained the attack was carried out by two Fulani jihadis.49 A Fulani individual was also named as one of three men who carried out the January 15, 2016, attack on the Splendid Hotel and Cappuccino Café in the Burkina Faso capital of Ouagadougou, providing further proof of the growing attraction of jihad among some members of the Fulani community.50

Another militant Fulani group, formed in June 2016, is the “Alliance nationale pour la sauvegarde de l’identité peule et la restauration de la justice” (ANSIPRJ). Its leader, Oumar al-Janah, describes ANSPIRJ as a self-defense militia that will aggressively defend the rights of Fulani/Peul herding communities in Mali while being neither jihadi nor separatist in its ideology. ANSPIRJ deputy leader, Sidi Bakaye Cissé, claims that Mali’s military treats all Fulani as jihadis. “We are far from being extremists, let alone puppets in the hands of armed movements.”51 In reality, al-Janah’s salafi movement is closely aligned with the jihadi Ansar al-Din movement and participated in a coordinated attack with that group on a Malian military base at Nampala on July 19, 2016, that killed 17 soldiers and wounded 35.52 ANSPIRJ’s Fulani military emir, Mahmoud Barry (aka Abu Yehiya), was arrested near Nampala on July 27.53

Fulani groups that have maintained their distance from jihadis in Mali include:

The Mouvement pour la défense de la patrie (MDP), led by Hama Founé Diallo, a veteran of Charles Taylor’s forces in the Liberian Civil War and briefly a member of the rebel Mouvement National de Libération de L’Azawad (MNLA) in 2012. The MDP joined the peace process in June 2016 by allying itself with the pro-government Platforme coalition.54 Diallo says he wants to teach the Fulani to use arms to defend themselves while steering them away from the attraction of jihad.55

“The Coordination des mouvements et fronts patriotiques de résistance” (CMFPR) has split into pro- and anti-government factions since its formation in July 2012.56 Originally an assembly of self-defense movements made up of Fulani and Songhaï in the Gao and Mopti regions, both factions have many former Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso members.57 The pro-government Platforme faction is led by Harouna Toureh; the split-off faction is led by Ibrahim Abba Kantao, head of the Ganda Iso movement, and is part of the separatist Coordination des mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA) coalition formed in June 2014. While Kantao appears to favor the separatism of Azawad, he is closer to the secular MNLA than the region’s jihadis.58

Conclusion

In highly militarized northern Mali, Fulani gunmen have begun to form organized terrorist or ‘self-defense’ organizations along established local patterns. If this became common elsewhere, it would remove community decision-making from locally based “cattle associations” and hand it to less representative militant groups with agendas that do not necessarily address the concerns of the larger community. In this case, the Fulani crisis could become intractable, with escalating consequences for West Africa.

In Nigeria, the state is not absent, as in northern and central Mali, but it is unresponsive. A common thread through all the attacks alleged to be the work of Fulani herdsmen, rustlers, or vigilante groups is the condemnation of state inaction by victims in the face of violence. This unresponsiveness breeds suspicion of collusion and hidden motives, weakening the state’s already diminished authority, particularly as even elected officials urge communities to take up arms in self-defense.

There continues to be room for negotiated solutions, but attempts to radicalize Muslim herders will quickly narrow the room for new options. Transforming an economic dispute into a religious or ethnic war has the potential of destroying the social structure and future prosperity of any nation where this scenario takes hold. For Islamist militants, the Fulani represent an enormous potential pool of armed, highly mobile fighters with intimate knowledge of local terrain and routes. In Nigeria, a nation whose unity and physical integrity is already facing severe challenges from northern jihadis and southern separatists, mutual distrust inspired by communal conflict has the potential to contribute to the outbreak of another civil war in Nigeria between northern Muslims and southern Christians and Animists.

Is the violence really due to “foreign terrorists,” “Boko Haram operatives,” and local gangsters posing as Fulani herdsmen? All are possible, to a degree, but none of these theories is supported by evidence at this point, and any combination of these is unlikely to be completely responsible for the onslaught of violence experienced in the Sahel. What is certain is that previously cooperative groups are now clashing despite the danger this poses to both farmers and herdsmen. The struggle for land and water has already degenerated into ethnic conflict in some places and is increasingly seen, dangerously, in religious terms by elements of Christian Nigeria. There is a real danger that this conflict could be hijacked by Islamist extremists dwelling on “Fulani persecution” while promoting salafi-jihadism as a radical solution. CTC

Dr. Andrew McGregor is the director of Aberfoyle International Security, a Toronto-based agency specializing in the analysis of security issues in Africa and the Islamic world.

Substantive Notes

[a] This article is based on primary sources from West African media as well as environmental and anthropological studies of the region.

[b] The Fulani/Peul are found in Nigeria, Benin, Egypt, Liberia, Mauritania, Sudan, Burkina Faso, Senegal, Togo, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ghana, Mali, the Gambia, Cameroon, Sierra Leone, Guinea Bissau, Côte d’Ivoire, Niger, Chad, and the Central African Republic.

[c] Boko Haram (a nickname for the group whose full name was Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wa’l-Jihad – People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad) changed its official name in April 2015 to Islamic State – Wilayat West Africa after pledging allegiance to the Islamic State movement. The West African Wilayat split into two groups after Islamic State leaders took the unusual step of removing Wilayat leader Abubakr Shekau. Shekau refused his dismissal and now competes with the “official” Wilayat West Africa led by Abu Musab al-Barnawi. “Boko Haram” continues to have wide popular usage for both factions. For more, see Jason Warner, “Sub-Saharan Africa’s Three New Islamic State Affiliates,” CTC Sentinel 10:1 (2017).

[d] This is based on the author’s own observations of developments in the Sahel over the past 20 years.

[e] One source declared the remarks were those of Chief of Defence Staff General Abayomi Olonishakin and were merely delivered by Brigadier Abubakar. See “Boko Haram is Gone Forever – CDS,” Today [Lagos], October 29, 2016.

[f] Though 40 was the number reported in Nigerian media, VOA gave a figure of 15 based on official police reports. See Chris Stein, “Farmer-Herder Conflict Rises across Nigeria,” VOA News, May 11, 2016, and United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, “Press briefing note on Mozambique and Nigeria,” April 29, 2016.

[g] The Yoruba are a West African ethnic group found primarily in southwestern Nigeria and southeastern Benin (“Yorubaland”). The Yoruba are roughly equally divided between Christianity and Islam, with some 10 percent remaining adherents of traditional Yoruba religious traditions. Religious syncretism runs strong in the Yoruba community, inspiring local religious variations such as “Chrislam” and the Aladura movement, which combines Christianity with traditional beliefs. Protestant Pentecostalism, with its emphasis on direct experience of God and the role of the Holy Spirit, is especially popular in many Yoruba communities.

Citations

[1] Taye Obateru, “Plateau Massacre: We did it – Boko Haram; It’s a lie — Police,” Vanguard, July 11, 2012.

[2] Olakunie Michael Folami, “Climate Change and Inter-ethnic Conflict between Fulani Herdsmen and Host Communities in Nigeria,” paper presented at the Conference on Climate Change and Security, Norwegian Academy of Science and Letters, Trondiem, Norway, 2010.

[3] Yomi Kazeem, “Nigeria now has a bigger internal security threat than Boko Haram,” Quartz Africa, January 19, 2017.

[4] Muhammed Sabiu, “At the mercy of cow rustlers: Sad tales of Zamfara cattle rearers,” Nigerian Tribune, February 2, 2014.

[5] “Delta community women protest Fulani herdsmen’s invasion,” Vanguard, October 25, 2016.

[6] “Herdsmen attacks sponsored by politicians, says APC chieftain,” Vanguard, August 30, 2016.

[7] “Nigerian Military to launch operation against violent herdsmen,” News Agency of Nigeria, October 29, 2016; Akinyemi Akinrujomu, “Military begins plans to tackle Fulani herdsmen menace,” Naij.com, October 28, 2016; “Military to launch operation against Fulani herdsmen,” The Nation Online [Lagos], October 30, 2016.

[8] Francis Igata, “I alerted security operatives before Fulani herdsmen attack, says Ugwuanyi,” Vanguard, April 30, 2016; “The New Terror Threat,” This Day [Lagos], May 2, 2016; Ibanga Isine, “Interview: Benue ‘completely under siege by Fulani herdsmen’ – Governor Ortom, Premium Times [Abuja], October 3, 2016.

[9] Shehu Umar, “Violent crimes sparking Hausa vs. Fulani clashes in Zamfara,” Daily Trust, October 15, 2016.

[10] Evelyn Usman, “Menace of Fulani herdsmen: A nightmare to police too,” Vanguard, February 27, 2016.

[11] “Buhari’s islamization agenda is real, he is implementing it gradually – Igbo Leaders,” Daily Post [Lagos], October 6, 2016.

[12] Danielle Ogbeche, “Stop making noise about Fulani herdsmen, Islamization – Sultan of Sokoto,” Daily Post [Lagos], October 11, 2016; Jasmine Buari, “Sultan of Sokoto speaks on the herdsmen-farmers conflict,” Naij.com, October 10, 2016.

[13] Sale Bayari, “Herdsmen vs the Military – Don’t Use Force,” Daily Trust, November 2, 2016.

[14] “Fulani herdsmen moving with guns are foreign terrorists, says Sultan,” Vanguard, September 12, 2016.

[15] Moses E. Ochonu, “The Fulani herdsmen threat to Nigeria’s fragile unity,” Vanguard, March 18, 2016.

[16] Joshua Sani, “10 States allocate grazing lands to herdsmen,” Today [Lagos], August 24, 2016.

[17] John Ameh, Femi Atoyebi, Sunday Aborisade, Kamarudeen Ogundele, Jude Owuamanam, Mudiaga Affe, Femi Makinde, Gibson Achonu, and Peter Dada, “N940m grazing reserves for herdsmen: Lawmakers fault Buhari,” Punch, May 21, 2016.

[18] Seun Opejobi, “Just like farmers; Fulani herdsmen have the right to live,” Daily Post [Lagos], November 1, 2016.

[19] Paul Obi, “Southern Kaduna Cries Out Over Fulani Persecution,” This Day [Lagos], October 11, 2016.

[20] “The Mission of Fulani Herdsmen,” Guardian [Lagos], October 30, 2016).

[21] Omololu Ogunmade, “Senate Rejects Grazing Reserve Bill, Says It’s Unconstitutional,” This Day [Lagos], November 10, 2016.

[22] Ebenezer Afanyi Dadzie, “Joint police-military team storm Agogo to flush out Fulanis,” Citifmonline.com, February 4, 2016.

[23] “Fulani menace will be fixed permanently – Mahama,” GhanaWeb, November 1, 2016.

[24] “Politicians overlook ranching law,” GhanaWeb, October 28, 2016.

[25] Senator Iroegbu, “Expert Proffers Solution to Fulani Herdsmen, Farmers Clashes,” This Day [Lagos], July 9, 2016.

[26] “War against Grazing: FCTA Prosecutes 16 Fulani Herdsmen, Impounds 32 Cattle, 38 Sheep,” The Whistler [Lagos], October 14, 2016.

[27] Ebuka Onyeji, “Abuja Administration Bans Movement of Cattle on Public Roads,” Premium Times, October 25, 2016.

[28] Olu Ojewale, “The Menace of Fulani Herdsmen,” Realnewsmagazine.net, April 7, 2014.

[29] Eromosele Ebhomele, “ARG warns Fulani herdsmen for threatening Ekiti people,” Naij.com, October 25, 2016.

[30] Eromosele Ebhomele, “Fayose urges Ekiti people to prepare for war against herdsmen,” Naij.com, October 26, 2016; Alo Abiola, “Fayose Holds Meeting with Herdsmen, Says No Grudge against Fulani,” Leadership [Abuja], November 2, 2016; Dayin Adebusuyi, “Farmers, Herders to be Grazing Law Enforcement Marshals,” Daily Trust, November 2, 2016.

[31] Eromosele Ebhomele, “Fayose urges Ekiti people to prepare for war against herdsmen,” Naij.com, October 26, 2016.

[32] Richard Ducayne, “Bishop Warns: Boko Haram Enlisting Herders as Fighters,” ChurchMilitant.com, August 10, 2016.

[33] Amy Furr, “Muslim Fulani Herdsmen Slaughter Dozens of Christians in Nigerian Village,” CSN News, October 27, 2016.

[34] “Mob attacks, burn 14 Fulani herdsmen in Kaduna,” Vanguard, October 17, 2016.

[35] Adams Abonu, “The Agatu Massacre,” This Day [Lagos], April 4, 2016; Omotayo Yusuf, “20 herdsmen killed, 83 cows slaughtered in Nasarawa,” NAIJ.com, May 2, 2016.

[36] Musa Abdullahi Kirishi, “National Assembly and price of rhetorics over Agatu,” Daily Trust, March 22, 2016; Emman Ovuakporie and Johnbosco Agbakwuru, “Agatu genocide: Benue lawmakers slam Buhari,” Vanguard, March 19, 2016.

[37] Abbas Jimoh, “Muslim rights group alleges genocide against Fulanis,” Daily Trust, April 22, 2014.

[38] Tony Adibe, Hope Abah, Andrew Agbese, and Adama Dickson, “‘115 Grazing Reserves in Nigeria Taken Over’ – Miyetti Allah,” Daily Trust, May 8, 2016.

[39] Tope Fasua, “Da Allah, cows are not Nigerian citizens,” Daily Trust, May 15, 2016.

[40] “Herdsmen deadly attacks stalled Agatu’s constituency projects, says lawmaker,” Pulse News Agency, February 1, 2017; Petet Duru, “Benue farmers/Fulani herdmen renewed clash claims 15 lives,” Vanguard, January 24, 2017; Hembadoon Orsar, “Many Feared Dead in Fresh Herdsmen Attack on Benue Village,” Leadership [Abuja], January 24, 2017.

[41] For Mali’s armed groups, see Andrew McGregor, “Anarchy in Azawad: A Guide to Non-State Armed Groups in Northern Mali,” Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor, January 25, 2017.

[42] Yvan Guichaoua, “Mali-Niger: une frontière entre conflits communautaires, rébellion et djihad,” Le Monde, June 20, 2016.

[43] “Mali: Abuses Spread South: Islamist Armed Groups’ Atrocities, Army Responses Generate Fear,” Human Rights Watch, February 19, 2016.

[44] “Violence in northern Mali causing a human rights crisis,” Amnesty International, February 16, 2012.

[45] “Mali: Abuses Spread South: Islamist Armed Groups’ Atrocities, Army Responses Generate Fear.”

[46] Ibrahim Keita, “Mali: Iyad Ag Ghaly affaibli, abandonné par Amadou Koufa!” MaliActu, January 7, 2017; O. Kouaré, “Mali: Amadou Kouffa; pourquoi il a trahi Iyad Ag Ghaly,” MaliActu, January 20, 2017.

[47] Idrissa Khalou, “Mali: Amadou Kouffa et l’Etat Islamique: ‘Creuse un trou pour ton ennemi, mais pas trop profond, on ne sait jamais,’” MaliActu, January 6, 2017; Boubacar Samba, “Mali: L’Etat Islamique du Macina,” MaliActu, January 7, 2017.

[48] “Al-Mourabitoune dévoile l’auteur de l’attaque de Gao,” al-Akhbar, January 18, 2017.

[49] “Mali: Al-Mourabitoune diffuse une photo des assaillants du Radisson,” RFI, December 7, 2015.

[50] “Al Qaeda names fighters behind attack on Burkina capital,” BBC, January 18, 2016; Morgane Le Cam, “Un an après l’attentat de Ouagadougou, le point sur l’enquête,” Le Monde, January 16, 2017. See also Andrew Lebovich, “The Hotel Attacks and Militant Realignment in the Sahara-Sahel Region,” CTC Sentinel 9:1 (2016).

[51] Mohamed Abdellaoui and Mohamed Ag Ahmedou, “Les Peuls, un peuple sans frontières qui accentue l’embrouillamini au Sahel,” Anadolu Agency, April 7, 2016.

[52] Alpha Mahamane Cissé, “Attaque d’un camp militaire dans le centre du Mali, revendiquée par un mouvement peul,” Mali Actu/AFP, July 19, 2016; “Mali: un mouvement peul revendique l’attaque contre un camp militaire à Nampala,” Jeune Afrique/AFP, July 19, 2016.

[53] “Mali arrests senior jihadist blamed for military base attack,” AFP, July 27, 2016.

[54] Adam Thiam, “Hama Founé Diallo: Itinéraire d’un rebelle peulh,” Le Républicain, June 27, 2016; Kassoum Thera, “Mali: La plateforme des mouvements d’autodéfense s’enrichit d’une adhésion de taille: Les vérités amères du président de la Haute cour de justice,” Aujourd’hui-Mali, July 2, 2016.

[55] Rémi Carayol, “Mali: Hama Foune Diallo, mercenaire du delta,” Jeune Afrique, July 18, 2016.

[56] Amadou Carara, “Changement à la tête de la CMFPR: Kantao remplace Me Harouna Toureh,” 22 Septembre, January 30, 2014.

[57] Ibrahim Maïga, “Armed Groups in Mali: Beyond the Labels,” West Africa Report 17, Institute for Security Studies, June 2016.

[58] Youssouf Diallo, “Mali: Le président de la CMFPR2, Ibrahima Kantao, justifie son alliance avec le Mnla: ‘Pour la paix, nous sommes prêts à nous allier avec le diable,’” 22 Septembre, December 29, 2014.

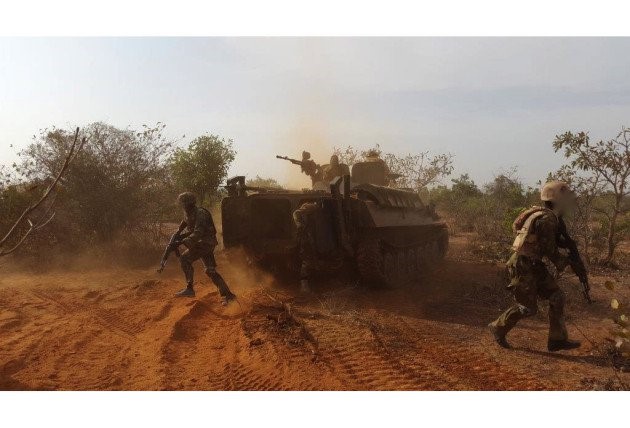

RCAF Helicopters over Mali (Corporal Ken Beliwicz/Canada DND/CAF)

RCAF Helicopters over Mali (Corporal Ken Beliwicz/Canada DND/CAF)