Andrew McGregor

June 17, 2005

The United States has made some strange alliances in the War on Terrorism, but none odder than its growing relationship with the ruling Islamists of Sudan. Once eager hosts of Osama bin Laden, Sudan’s Islamist movement has since split, with the two factions now fighting a proxy war in Darfur. In the 1990s, the U.S. rejected every initiative offered by the Sudanese to cooperate on counter-terrorism issues, including an offer to extradite Osama bin Laden. The Sudanese government’s willingness to share its copious intelligence on al-Qaeda has now bought it some immunity from responsibility for the atrocities in Darfur. The CIA has initiated close contacts with Sudanese intelligence director Major-Gen. Salah Abdallah Gosh, who has also been identified in Congress as a war crimes suspect for his exploits in Darfur. In a sign of growing cooperation many Sudanese prisoners at Guantanamo Bay have been released to Sudanese authorities. Besides intelligence sharing, the U.S. is also keen to protect the peace agreement that will end the North-South civil war and release vast new reserves of oil onto the market.

The Arming of Darfur

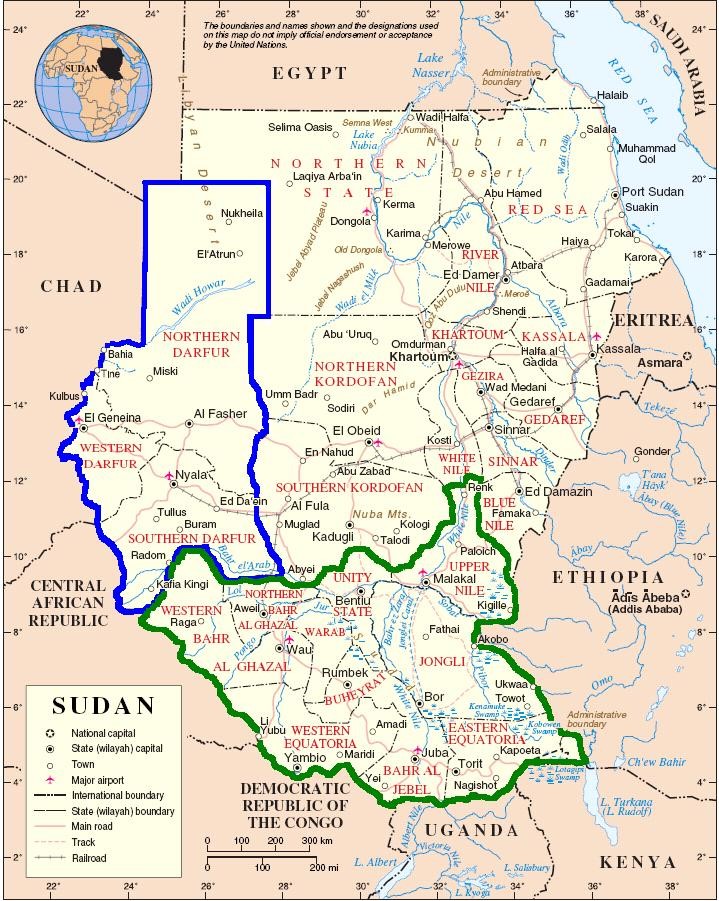

During the 1980s the Umma Party government of Sadiq al-Mahdi and private sponsors (including General Swahr al-Dahab, a former President of Sudan) began arming Arab militias in South Darfur known as Murahalin. The object of the militias was to put pressure on the Bahr al-Ghazal heartland of the Dinkas (the leading tribe in the Sudanese Peoples Liberation Army), which lies directly south of Darfur. [1] With the arms came a Khartoum-based ideology of Arab superiority. The Murahalin carried out their duties with enthusiasm. Looting, murder, abductions and all manner of atrocities were practiced, all without government responsibility, as the militias were not part of the regular army. The Murahalin would serve as the model for the Janjawid raiders of today.

Arms flooded Darfur as the region became a staging base for armed groups involved in the struggle to control Chad in the 1980s. In the 1970s and 1980s many Darfuri followers of the Umma Party were forced into exile in Libya, where they joined Muammar Qaddafi’s Islamic Legion, a force of Arabs, Tuareg and West Africans. Many of these exiles absorbed heavy doses of the radical Arabist ideology propagated by Qaddafi at the time. Qaddafi proposed the creation of an “Arab corridor” through North Africa, which implied the expulsion or extermination of the non-Arab tribes of central Darfur. Based in Libyan-occupied northern Chad, the Islamic Legion became an important conduit for the cross-border arms trade. Law enforcement vanished and in its absence even peaceful communities were forced to arm themselves.

Ecological pressures began to force the nomadic Zaghawa and the northern Arab tribes into the territory of the Fur, the pre-colonial rulers of the region. Attempts to settle there were opposed by the Fur and fighting broke out after which the army focused its efforts on punishing the non-Arab Zaghawa. The Arab tribes were given a free hand to seize land, resulting in the death of thousands of Fur and the displacement of tens of thousands more. In 1991, an ill-fated attempt was made by the southern-based Sudanese Peoples Liberation Army to open a new Fur-led front in the civil war. The local SPLA leader, Daoud Bolad, was a former member of Hassan al-Turabi’s Islamist National Islamic Front (NIF) but became involved in Fur self-defense militias in the late 1980s. He emerged in 1991 as leader of the new SPLA front in Darfur. Bolad’s brief military success was followed by defeat and death in prison.

In the late 1990s, even as oil money began to pour into Khartoum, funds for government services in Darfur began to dry up. Security was virtually non-existent in the countryside and military garrisons rarely ventured out. Gun-rule made an unwelcome return. In 1998 and 1999, northern Arab tribes began moving their herds into Masalit lands earlier than usual, leading to violence in which the Masalit got the worst of it. Thirty thousand Masalit fled to Chad where they were still attacked by Arab militias.

In the late 1990s, even as oil money began to pour into Khartoum, funds for government services in Darfur began to dry up. Security was virtually non-existent in the countryside and military garrisons rarely ventured out. Gun-rule made an unwelcome return. In 1998 and 1999, northern Arab tribes began moving their herds into Masalit lands earlier than usual, leading to violence in which the Masalit got the worst of it. Thirty thousand Masalit fled to Chad where they were still attacked by Arab militias.

The Turabi Factor

Former leader of the Muslim Brothers and founder of the National Islamic Front, Hassan al-Turabi’s life-long goal of establishing an Arabized and Islamic state in Sudan has run roughshod over the cultural and religious sensibilities of many Sudanese. His first attempt at introducing Islamic law as Attorney-General, the “September Laws” of 1983, was reviled by Muslims and Christians alike. Its emphasis on huddud (traditional Islamic punishments, including amputations and crucifixion) shocked most Sudanese. As the civil war worsened and then-President Ja’afar Nimeiri’s position became more precarious in coup-prone Khartoum, Turabi and the Muslim Brothers were rounded up and blamed for the rapidly deteriorating security situation.

Nimeiri’s overthrow brought a brief spell of ineffective civilian government until Turabi joined Brigadier Umar al-Bashir in an Islamist coup in 1989. Bashir was installed as President with Turabi as an unaccountable power behind the throne. Strict interpretation of Islamic law returned and a brutal campaign against the non-Arab Nuba of Kordofan in 1991-1992 targeted both Muslims and Christians. Even mosques were destroyed in an explicit rejection of non-Arab Islam. Under the influence of Turabi and his deputy ‘Ali ‘Uthman Muhammad Taha the war in the South became a jihad against disbelievers. The ruling arrangement lasted until 1996 when disagreements between Bashir and Turabi seemed to leave the latter in the ascendance. However Turabi miscalculated in 1999 when he introduced legislation restricting the power of the president. Consequently Bashir reasserted his authority and the NIF split under the resulting pressure. Bashir’s supporters became the governing National Congress Party while Turabi’s followers went into opposition as the Popular Congress Party (PCP). Most of the NIF’s membership in Darfur joined the PCP.

Turabi was arrested in 2001 under emergency laws and sent to Khobar prison. His offence was opening peace negotiations with the SPLA without government approval. Turabi was not only held in solitary confinement, but was judged so dangerous that a wall was built around his cell to prevent any interaction with other prisoners. Eventually he was released to house arrest and freed in October 2003.

On April 15, 2005, a Sudanese court sentenced 21 soldiers and 3 others for mounting a coup attempt in March 2004. Two-thirds of the convicted were members of Turabi’s PCP and many of the leaders were military officers from Darfur. Turabi was re-arrested at the time but not charged, though he accused the government of arming the Janjawid raiders of Darfur and purging Black African officers from the army. Following the alleged coup attempt the government suspended the PCP from political activities, partly on charges of aiding insurrection in Darfur. State prosecutors also alleged participation by Turabi in a second coup attempt in September 2004. Most of those charged were from Darfur and alleged by the government to be PCP members. Again Turabi was not charged even though the Attorney-General claimed to have evidence he “indirectly” planned the coup.

After his release, Turabi denounced the government’s actions in Darfur and called for greater political representation for the region in the central government. He also asserted that the government of Chad was responsible for some of the violence in Darfur. [2] The allegations may refer to military aid provided by the Zaghawa-dominated government in Chad to their Zaghawa cousins in the rebel Sudan Liberation Army.

There are many signs that Turabi uses the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM – the Islamist rebel group in Darfur) as a proxy army in his struggle against the government. Turabi covers his own complicity in the Darfur outrages by blaming the Sudanese government for encouraging militias and tribes to fight each other. According to Turabi, PCP members fighting alongside the JEM do so without his authorization. Turabi is playing a dangerous game and has received clear warning from the President: “It would not be difficult for us to bring in Turabi, to issue a presidential decree and have his head chopped off. We could do it and our conscience would not be bothered” [3]

Arab or African?

While the conflict in Darfur has its ethnic and political dimensions, it is largely sparked by the loss of nomadic pasture-lands to desertification or absorption into fenced-off farmland. The conflict also revolves around the traditional marginalization of Darfur, which is poorly represented in the central government and receives little development assistance. To complicate the issue, Darfur has also become a battleground in the ever-shifting web of political rivalries of Khartoum’s Islamists, bent on exploiting Sudan’s Arab/African identity crisis.

The roots of the conflict run deep in Darfur’s history. For centuries the camel-raising Arabs of north Darfur and the cattle-owning Arabs of South Darfur (the Baqqara) were reluctant subjects of the African Muslim Fur Dynasty. Tribute was often collected from the Arabs by force. Islam was better established in the Fur capital than amongst the nomadic Arab tribes and the Fur Sultan’s monopoly of the slave and ivory trade brought significant wealth to the kingdom.

The ancient sultanate was seized in 1874 by the slave army of Arab freebooter Zubayr Pasha and turned over to the Egyptian government. The Mahdi’s rebellion in the early 1880s brought down the Egyptian regime before going on to conquer most of the Sudan. After the Mahdi’s death, his successor, a Baqqara Arab from Darfur, brought the Baqqara tribes to Khartoum where they dominated all of Sudan. A succession of Fur “shadow-sultans” continued to fight for the restoration of the sultanate. The arrival of Kitchener’s British-Egyptian army in 1898 destroyed the power of the Baqqara Arabs.

Determined to eliminate the Sultan during WWI, the British began arming the Arab tribes of southern Kordofan and Darfur in preparation for an invasion of the Sultanate. The veteran Arabists who dominated British intelligence felt comfortable dealing with the Arabic-speaking nomads but had little regard for the “black” Fur. Encouraged by what seemed the approval of the Khartoum government, the Arab tribes wreaked havoc in Darfur and were only restrained with great difficulty at the end of the campaign. The Sultan’s death marked the end of the once-powerful African tribes as a political force in Darfur. Every effort was made to eliminate the legacy of Fur rule in the region, which gradually became a forgotten outpost, even after Sudanese independence in 1956.

There was always a high degree of mobility in Darfur between ethnic groups and intermarriage was common. Most tribes, both nomadic and sedentary, had sections formed from members of other tribes or ethnic groups. During British rule a great deal of effort was devoted to defining tribal borders in neat patterns that had little to do with the incredibly complex system of seasonal land use. These artificial divisions were then used to allocate dar-s (homelands) to each tribe. In the south, where Baqqara tribes had historically acknowledged land-claims, the system worked satisfactorily, but the Arabs of the north, who wandered with their herds in the pastures between farming communities, were never granted their own dar-s. This early interference in Darfur’s social structure laid the foundation for today’s conflict.

Notes:

- The SPLA is not to be confused with the Darfur-based SLA (Sudan Liberation Army)

- ‘Turabi slams Government’, Sudan Mirror 1(11), March 1-14, 2004.

- ‘Sudanese president urges opposition party to dump Turabi’, AP, Sept. 27, 2004.

This article first appeared in the June 17, 2005 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor