Andrew McGregor

A Lecture Delivered to the Civil War Roundtable, Royal Canadian Military Institute, Toronto, February 5, 2020

Introduction

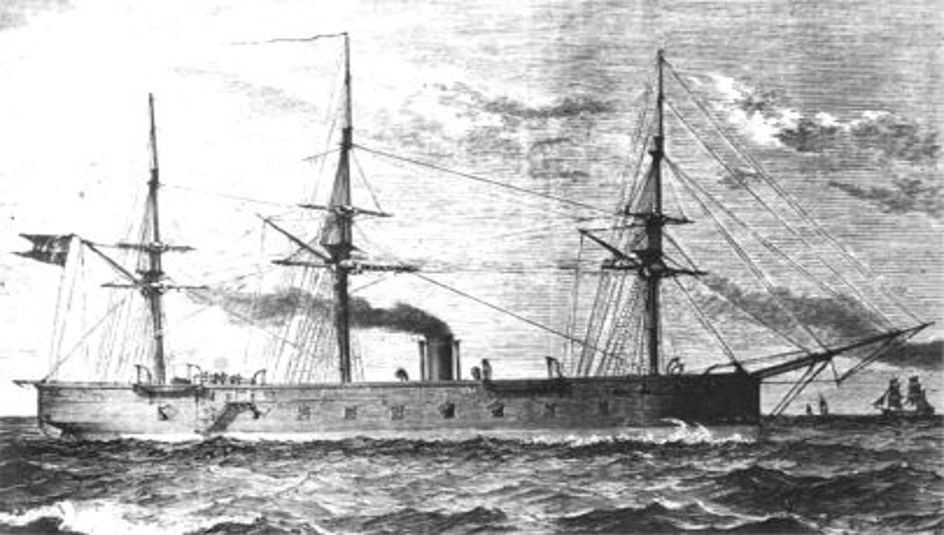

Though Civil War battlefield tactics had difficulty in shaking off the influence of the Napoleonic wars, rapid change and innovation were hallmarks of the naval part of the Civil War from the beginning. The wooden sailing ships armed with smoothbore, muzzle-loading guns were soon replaced by iron ships powered by steam engines and armed with rifled, breech-loading guns. This process was far from smooth, however, and expediency and necessity fuelled innovation as much as improved technology. While the ironclads were the war’s greatest contribution to naval architecture, their lesser-known cousins, the shallow-draft tinclads, timberclads and cottonclads, performed vital service for both sides.

These ships fought on an enormous maritime front, including the Gulf of Mexico and 700 miles of the Mississippi River as well as its great tributaries, most notably the Tennessee River, the Red River and the Yazoo River. Seizing control of the Mississippi’s southern reaches was part of the Union’s grand plan to strangle the Confederacy through a coastal blockade and a two-pronged takeover of the Mississippi that would split the south and diminish its ability to wage war. The plan was fine, but the north had no ships for an offensive river campaign and the south had none to mount a defense. The construction of naval ships for river work began quickly on both sides, though both parties found it quicker to use existing ships modified for naval work. The variety of these existing ships led to an intense period of experimentation and innovation in an effort to gain the upper hand, reviving ancient tactics and producing the poor cousins of the famous ironclads, the less well-known tinclads, timberclads and cottonclads that fought just as hard.

The Timberclads

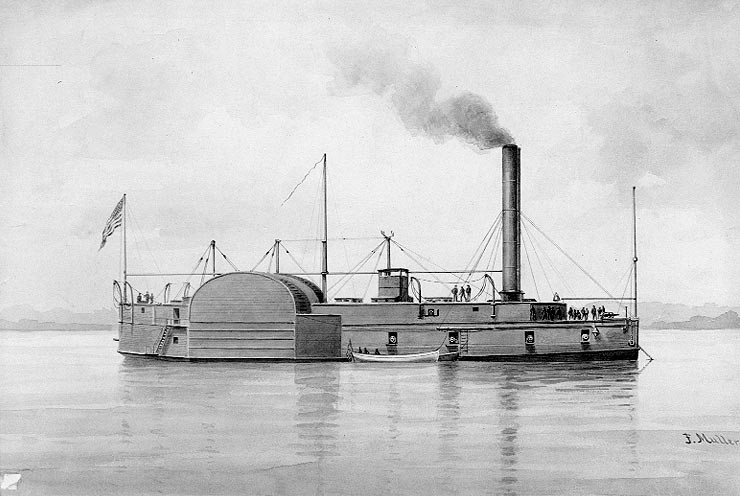

Though the Union’s naval efforts on the Mississippi first came under control of the US Army, certain officers were released by the navy to assist in the formation and command of the river fleet. Work began on the construction of ironclads, but in the meantime three sidewheel steamers, the Lexington, the Tyler and the Conestoga, were purchased for conversion into naval ships.

With high sides that invited enemy fire and engines above the water-line that could easily be put out of action, the three steamers were manifestly unfit for combat. Their conversion into battle-ready craft was put in the hands of naval architect Samuel Pook, who lowered the engines, reinforced the hulls and reduced the height of the superstructure. Decorative trim was removed and the glass pilot houses were replaced with stronger wooden structures. The urgent need for river-going warships could not be filled through the slow and still experimental construction of ironclads, so the steamers were fitted with the five-inch thick oak beams that gave the ships their name – timberclads. This wooden armor was capable of defending against small-arms fire, but was largely ineffective against shot and shell. The work, carried out in Cincinnati, was judged to be of low quality and the conversions were plagued by the usual demands by local businessmen for lucrative government contracts.

Nonetheless, the timberclads went into service at Cairo (Care-O), Illinois, in August 1861 with naval crews under army command.

From the beginning, the Tyler and Lexington usually worked in tandem. The Tyler carried one 32-pounder smoothbore and six 8-inch smoothbore guns, while the Lexington carried two 32-pounder smoothbores and four 8-inch smoothbores. The Conestoga, the weakest of the three, carried four 32-pounder smoothbores. (For those unfamiliar with naval gunnery, the weights refer to the size of the shot, measured by weight or circumference, rather than the size of the gun).

The armament of the Tyler and Lexington was improved in late 1862, when they were issued with 30-pounder rifled guns well suited for work against riverside defensive works. This was the timberclads’ primary role, and they played an important part in forcing the surrender of Forts Henry and Donelson on the Tennessee River.

During the Battle of Shiloh (April 6-7 1862), the Confederates attempted to anchor their right flank on the Mississippi and drive the Union forces into the river. The timely arrival of the Tyler and the Lexington at Pittsburg Landing prevented this deployment. The timberclads then supported a general advance with their guns. Grant later acknowledged the important role played by the ships in preventing a disastrous Federal defeat. In February 1863, the Lexington again saved the day when it arrived at Fort Donelson just as the defenders had run out of ammunition, preventing the Confederates from recapturing the fort.

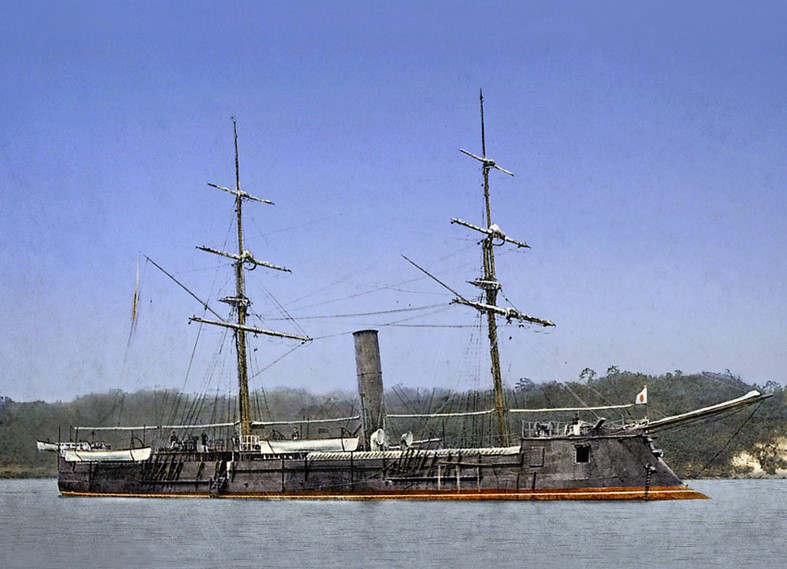

Confederate Cottonclads

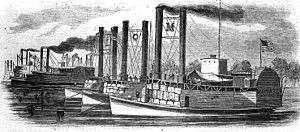

With warehouses full of cotton that could not be brought to market, the Confederates found a novel use for it as armor for its converted steamers.  Cottonclad CSS Stonewall Jackson

Cottonclad CSS Stonewall Jackson

The cottonclads’ boilers and engines were protected by 500 lb bales of compressed cotton. Sometimes the bales were sandwiched by double pine bulkheads. Many of the rams were converted wooden tugboats or towboats, preferred for their strong “walking-beam” steam engines.

Eventually the Union would also adopt cotton as a cheap and quick means of providing some protection to the crews of its river steamers.

Though the war brought an end to most commercial river traffic, experienced rivermen were hard to find for both sides, many of them having enlisted in the armies. The Union’s War Department began to transfer these men to their river craft, along with a transfer of naval officers to army command. Discipline and efficiency began to improve once the ships were transferred to navy command in 1862. The Confederates had greater difficulty – requests for the return of rivermen from the army to the river craft were frequently met with transfers of the infirm, incapable and incompetent instead. River pilots were in high demand and both sides made a practice of offering captured pilots financial incentives to change sides.

Battle of New Orleans, April 24, 1862

Confederate control of the Mississippi rested on two bastions, New Orleans and its outer defense works in the south, and Forts Donelson and Henry in the north.

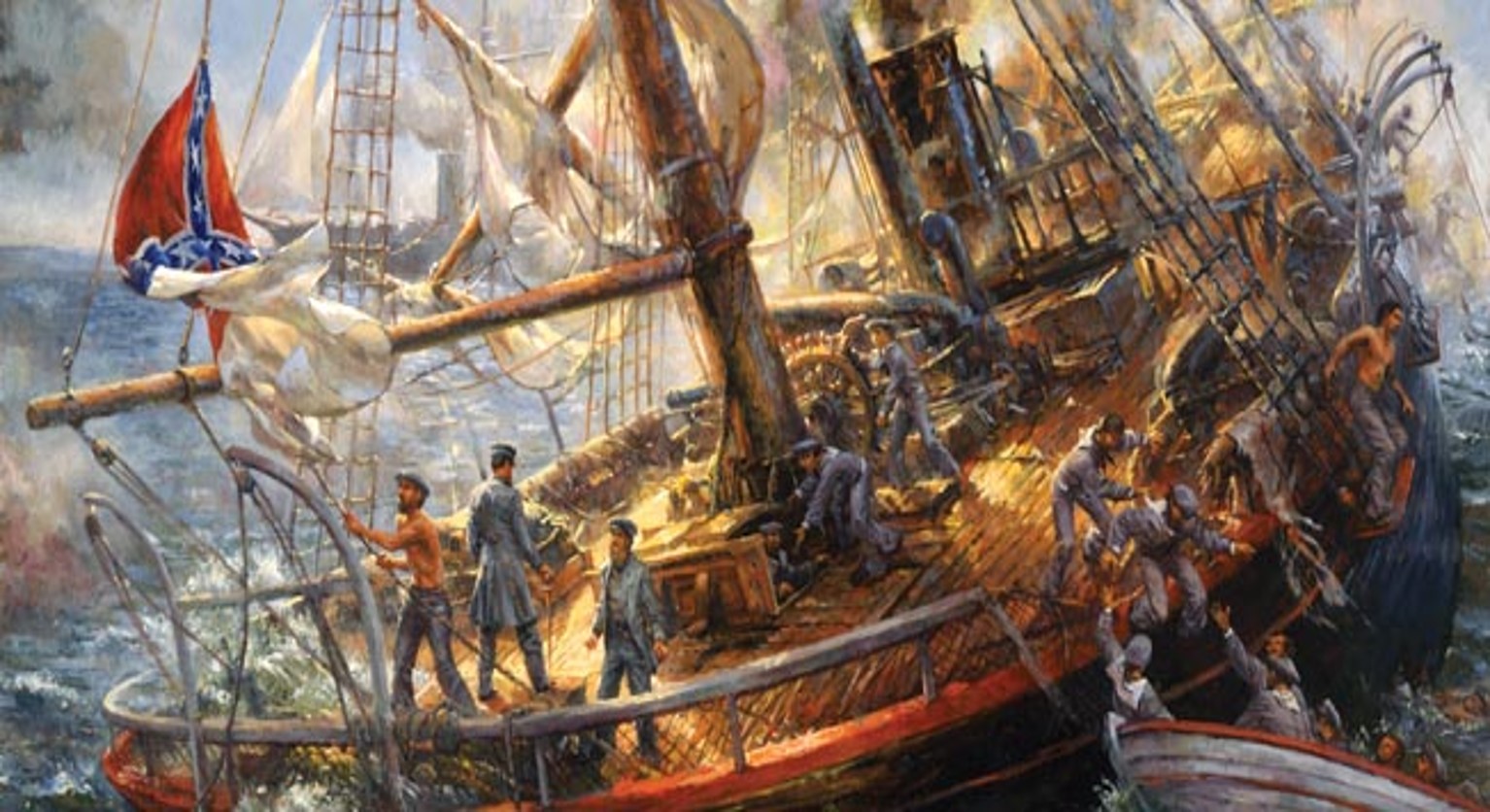

The LSNS Governor Moore Fires through its Own Bow to Sink the USS Varuna

The LSNS Governor Moore Fires through its Own Bow to Sink the USS Varuna

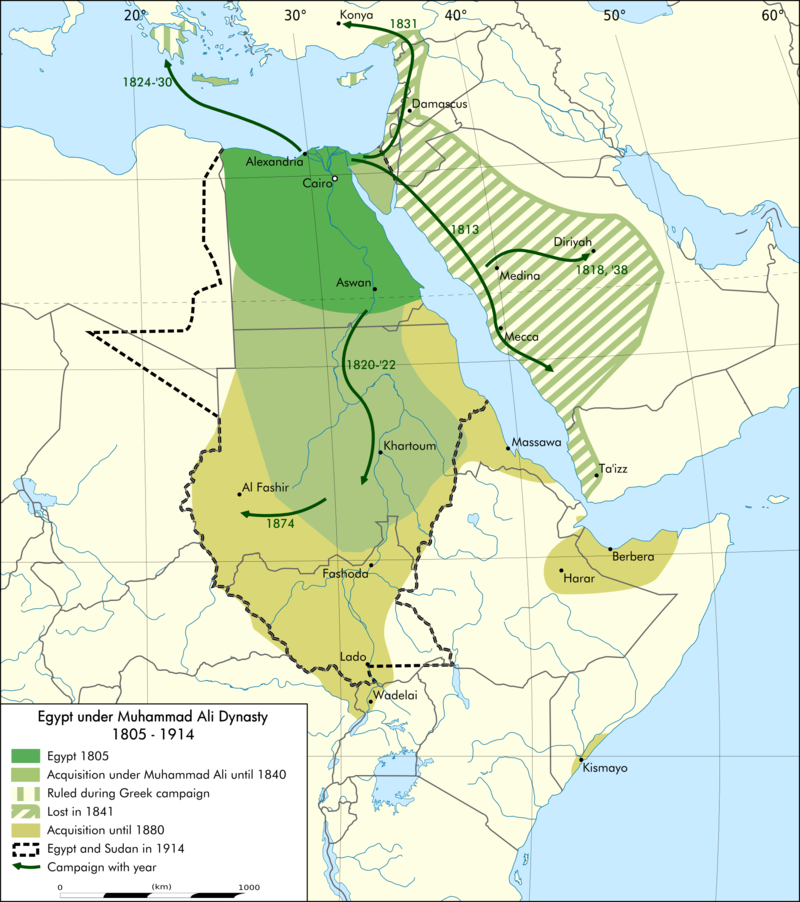

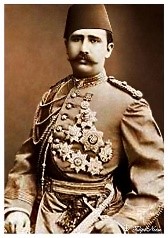

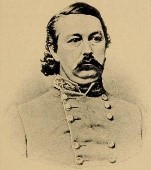

The small Confederate river fleet that met Commodore Farragut’s squadron south of New Orleans on April 24, 1862 consisted of two gunboats and two ironclads under the command of the Confederate Navy, six lightly armed cottonclads and rams under the command of the Confederate Army, as well as two sidewheel cottonclad rams, the Governor Moore and the General Quitman, that were part of the Louisiana State Navy. The Governor Moore was commanded by Captain Beverley Kennon, whom some of you might remember from one of my earlier talks as the designer of Alexandria’s defenses while attached to the Egyptian Army after the Civil War. During the battle, the Union gunboat Varuna was rammed on the starboard side by Captain Kennon’s Governor Moore. With the two ships locked together, Kennon discovered the Governor Moore’s bow gun could not be sufficiently depressed to fire on the Varuna, so he ordered the gun to fire twice through his own ship’s bow into the Varuna. Kennon freed his ship and again rammed the Varuna in nearly the same spot. The Confederate ram Stonewall Jackson rammed the Varuna once more to polish her off. The Federal fleet then concentrated its fire on the Governor Moore, sending it to the bottom of the river.

The defeat of the Confederate fleet sealed the fate of New Orleans, the largest city in the Confederacy, which surrendered to Farragut days later.

The Ellet Rams

Colonel Charles Ellet Jr. was one of the most forceful proponents of reviving the ram as a naval weapon. Ellet published a pamphlet advocating the use of rams in 1855, but the US Navy took no interest. The ram had been the centerpiece of naval tactics in the ancient world for centuries, but was reliant on the ability of the galleys that carried it to reverse direction by its oars to pull the ram back from a punctured ship and prevent the attacking vessel from being drawn down into the deep along with its victim. As galleys were gradually replaced with sailing ships that were less maneuverable in tight quarters and the introduction of gunpowder enabled ships to sink each other at a distance, the ram fell out of use, seemingly forever. The introduction of steam, however, with engines capable of running in reverse, had made the ram a viable weapon once more, especially for close-quarters action of the type that could be expected in river warfare. Both the Federals and Confederates would adopt the ram as the primary weapon on many of their river gunboats.

In 1862, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton gave Ellet the task of creating a ram flotilla consisting of seven converted sidewheelers and sternwheelers. The ram bows were built of 5 inches of oak encased in iron but retained their original shape rather than the projecting “beak” typical of the ancient rams. These lightly armed ships, with reinforced hulls to withstand the force of a collision, were intended to serve alongside the timberclads on the rivers. Rams could be dangerous even to their own side; accidental collisions involving a ram usually ended with the sinking of the ship that was struck. The regular navy was unimpressed by Ellet’s designs, deeming them unsuitable for combat.

Ellet was allowed to choose the commanders of his new rams. Nepotism was his guiding light in these choices, as he chose brothers, nephews and even his own 19-year-old son Charles Rivers Ellet as commanders.

Battle of Plum Point Bend, May 10, 1862

The Confederate River Defense Fleet ran into the Union’s Mississippi River Squadron four miles north of Fort Pillow, Tennessee on May 10, 1862. The place was known as Plum Point Bend. The Confederate fleet attacked Union ironclads of the Mississippi River Squadron during a thick morning fog. The General Bragg slowed the Federal ironclad Cincinnati by ramming it, allowing the General Sterling Price to ram the ironclad’s stern, completely disabling it. The Sterling Price was badly damaged in the engagement, but was quickly repaired in time for the later Battle of Memphis.

The Confederate River Defense Fleet ran into the Union’s Mississippi River Squadron four miles north of Fort Pillow, Tennessee on May 10, 1862. The place was known as Plum Point Bend. The Confederate fleet attacked Union ironclads of the Mississippi River Squadron during a thick morning fog. The General Bragg slowed the Federal ironclad Cincinnati by ramming it, allowing the General Sterling Price to ram the ironclad’s stern, completely disabling it. The Sterling Price was badly damaged in the engagement, but was quickly repaired in time for the later Battle of Memphis.

Though the Union squadron consisted mostly of ironclads assigned to protect mortar boats bombing Fort Pillow, the Confederate cottonclads won the day with their surprise attack, ramming and sinking two Federal ironclads, the Cincinnati and the Mound City.

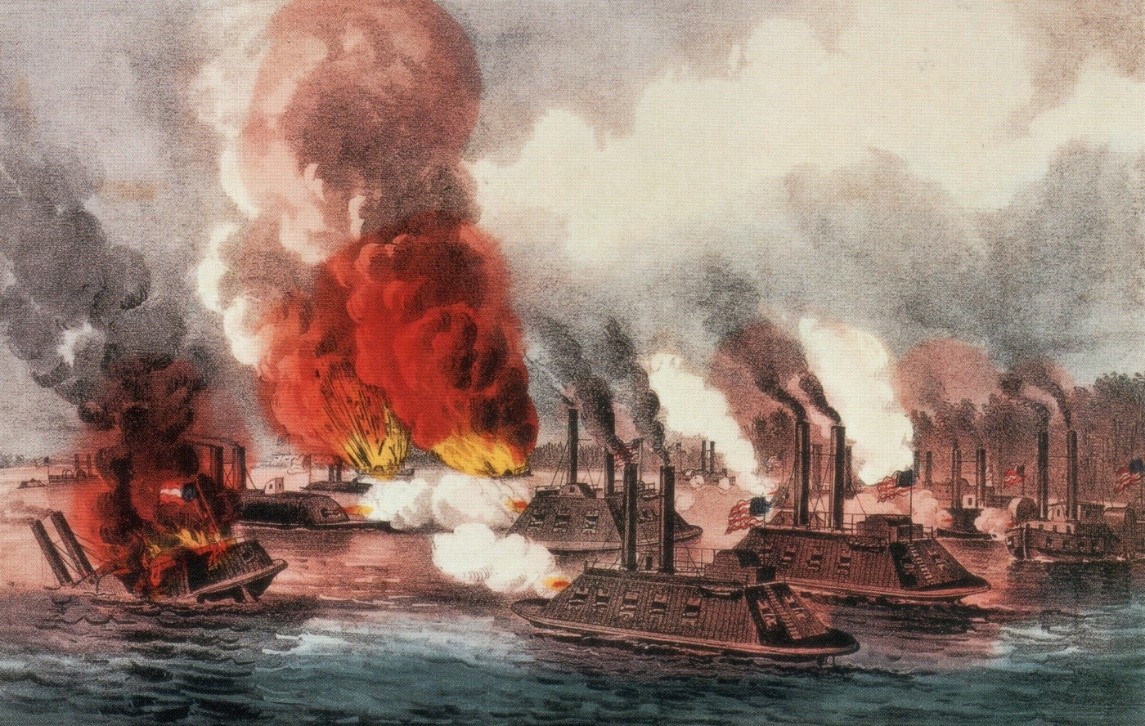

Battle of Memphis, June 6 1862

The Confederate River Defense Fleet consisted of 8 cottonclad sidewheel rams converted under the direction of Colonel WS Lovell. The fleet was run by the War Department rather than the navy and was charged with the defense of the upper reaches of the Mississippi.

Though faster than the Union ironclads, the cottonclads were no match in battle. All the ships of the River Defense Fleet were sunk, burned, captured or run aground in the battle, which was watched by thousands from the river bluffs.

The battle began as Ellet’s flagship, the USS Queen of the West rammed the CSS Colonel Lovell, splitting her in two. Before the Queen could pull back, she was in turn rammed by the CSS Sumter. There was little in the way of strategy in the battle as it quickly descended into a chaotic brawl.

The General Price and General Beauregard both attacked the USS Monarch, but collided with each other, leaving both as helpless targets for federal rams. The General Beauregard received a shot to her boiler from the Monarch, scalding to death most of its crew, save for 14 terribly burned men who were rescued by the Monarch. Colonel Ellet, who commanded the Union fleet, was wounded in the battle and died 15 days later. The General Price, the best armed of the Confederate rams, sank after colliding with the USS Queen of the West. After the battle, the ram was raised and repaired before entering Union service. The ship joined Admiral Porter’s ironclads in running the blockade off Vicksburg on April 16, 1863, an important step in the fall of the city. The General Price took part in the Red River Campaign, but in March 1864 it accidentally rammed the USS Conestoga and sank her.

One of the ships that had helped sink the ironclad Cincinnati at Plum Point Bend was the CSS General Bragg, named for Confederate General Braxton Bragg. The ship was badly damaged in the battle, but repaired in time to take part in the Battle of Memphis. The General Bragg ran aground during the battle and was captured by Federal troops. After repairs, the ship was brought into Union service as the USS General Bragg. She spent 15 months patrolling the Mississippi, but was disabled by a Confederate battery in Louisiana in June 1864.

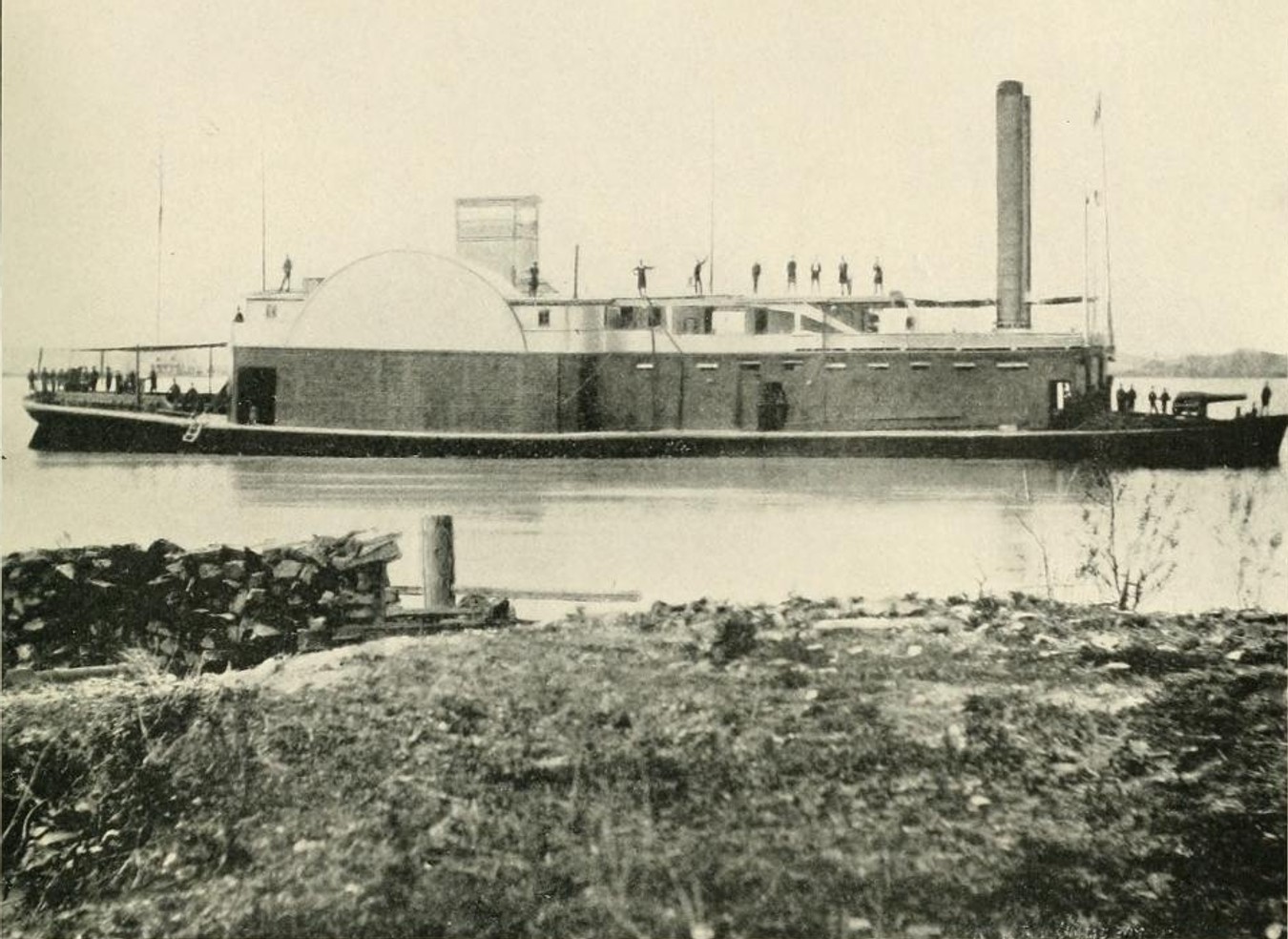

The Tinclads

After the Battle of Memphis, the Union had little use for its rams, which were designed almost exclusively for offensive naval actions. Shallow draft river steamers were now armed and altered by the addition of a thin belt of metal armor. Commonly known as “tinclads,” these steamers became the workhorse of Federal “brownwater” naval operations.

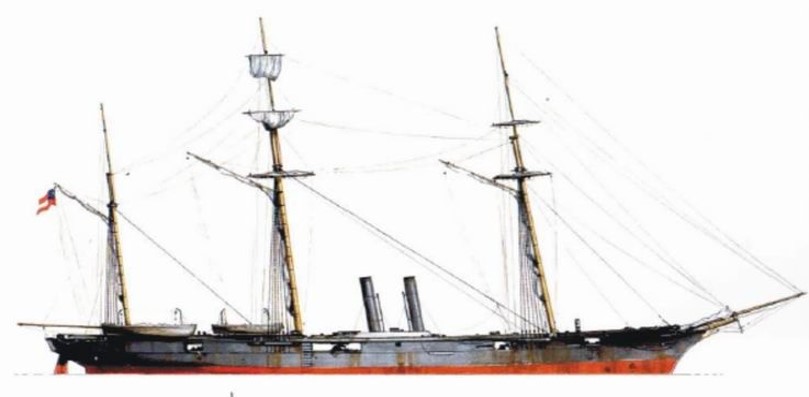

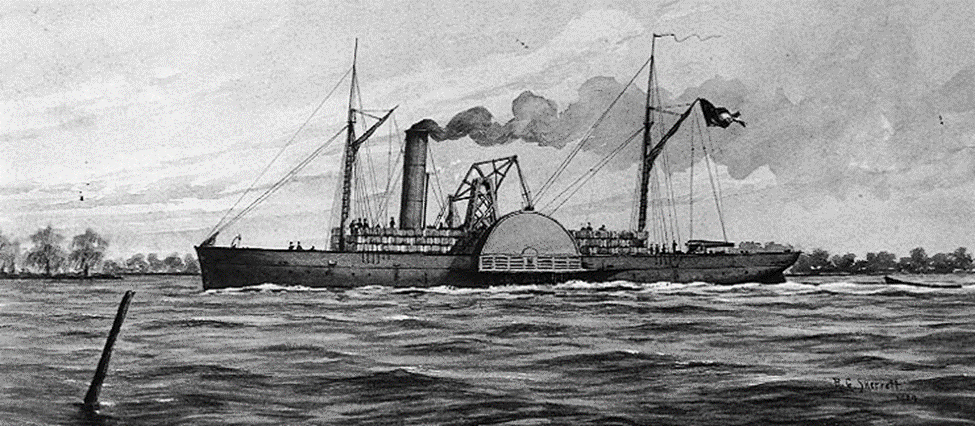

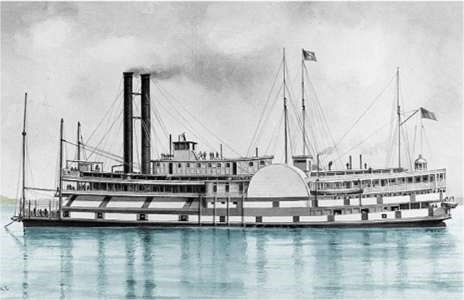

Sidewheel Tinclad USS Black Hawk

Sidewheel Tinclad USS Black Hawk

While the rams were built to engage Confederate ships, the Union purchased dozens of sidewheel and sternwheel flat-bottomed steamers for other duties on the rivers, such as patrols, fire support and transport escort. In their conversion to military service, the steamers were equipped with a light iron sheeting up to an inch thick capable of repelling small arms fire. Tin was not actually used – the term “tinclad” was only meant to distinguish these steamers from the heavier and more formidable ironclads. The flagship of the 69-ship fleet of tinclads, as they came to be called, was the USS Black Hawk, a former ocean-going luxury passenger steamer named New Uncle Sam. The most powerful of the tinclads was the USS Ouachita, a captured Confederate steamer that was armed with five 30-pounder Parrot rifles, eighteen 24-pounder smoothbores and fifteen 12-pounder smoothbores. Though the tinclads were typically slow, they carried between four to eight guns and performed valuable work that ships with a deeper draft could never accomplish.

With their light armor providing some protection from small arms fire, the tinclads carried out patrols, guarded river crossings, carried dispatches, cleared mines, provided fire support to land operations, escorted transports, shipped prisoners, towed ironclads and skirmished with Confederate guerrillas. It is difficult to imagine Federal success in the Western theater without the contribution of these converted river steamers.

Yazoo River Expedition to Vicksburg

Frustrated in their attempts to take the city of Vicksburg from the Confederates, Union commanders devised a plan to flank the city’s riverside defenses by sending a naval expedition through the backwaters and bayous of the Mississippi Delta to reach the Yazoo River and eventually Vicksburg.

The flagship of the expedition was the USS Rattler, a tinclad sternwheeler that had played an important part in the capture of Fort Hindman from the Confederates and the capture of its 6500 man garrison.

However, the going was extremely tough for the five tinclads, two ironclads and transport steamers of the expedition carrying 6,000 troops. Shallow water, felled trees, overhanging limbs and driftwood slowed the expedition’s progress, while exhausted men complained of having to “dig the gunboats out of the woods.” The slow pace permitted Confederate General Pemberton to build a rudimentary fort in their path. As the narrow channel prevented the gunboats from deploying anything more than the bow gun of its lead ship, the expedition was finally called off. The Rattler was driven aground by a storm in 1864, where its guns were salvaged before Confederates burned it.

Indianola vs. Queen of the West, February 24, 1863

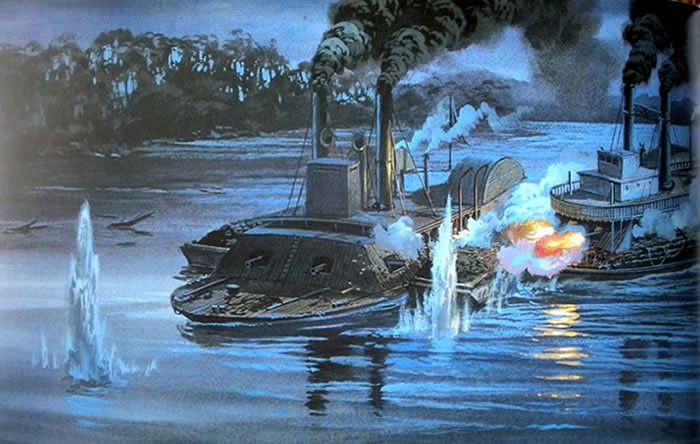

The CSS Queen of the West Attacks the USS Indianola on the Red River (Tom W. Freeman)

The CSS Queen of the West Attacks the USS Indianola on the Red River (Tom W. Freeman)

While patrolling the Mississippi near Vicksburg, the Federal ironclad Indianola encountered a Confederate flotilla consisting of the newly captured Queen of the West, the Webb and two smaller cottonclads carrying troops for boarding operations. The Webb and the Queen of the West rammed the Indianola seven times, forcing her to run aground, partly sunk. The crew surrendered and the Confederates began planning to raise and repair the ship. Admiral David Porter, in command of the Union’s Mississippi fleet, described her loss as “the most humiliating affair that has occurred during this rebellion.”

However, it was now the Confederates’ turn to experience a little humiliation. Federal troops quickly assembled a fake ironclad, a 300-foot long hollow wooden vessel with logs for guns and smudge pots to generate smoke from its fake stacks. Flying a skull and crossbones flag at its bow and the message “Deluded Rebels, Give In,” the imposter was carried by the current past the guns of Vicksburg, which made a furious attempt to sink the intruder. Confederate vessels on the river turned away rather than confront this new and apparently powerful ironclad, abandoning the salvage crew working on the Indianola. Panicked, the salvage crew spiked the Indianola’s guns and blew her up before fleeing. Without firing a shot, the great hoax deprived the Confederates of a potent addition to their river fleet.

Battle of Galveston

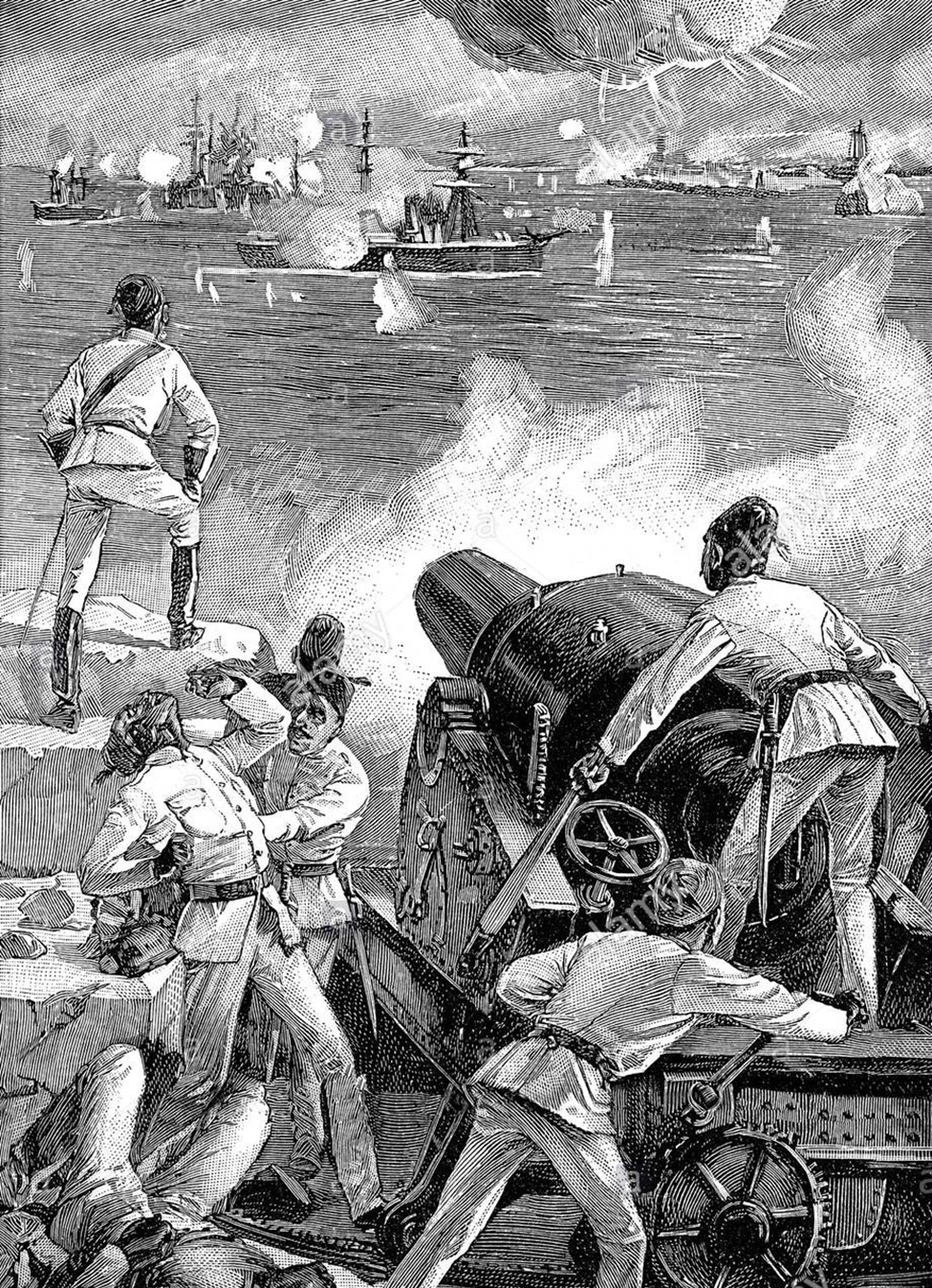

In the early morning of January 1, 1863, Confederate forces under General John B. Magruder launched an attack intended to retake the city of Galveston from Union forces. Off Galveston a small fleet of six federal ships lay at anchor, with only one, the USS Westfield, ready to sail, though it quickly ran aground. Confederate troops retook the forts and turned the guns on the Federal ships, while infantry attempted to board them.  Battle of Galveston

Battle of Galveston

Two Confederate ships arrived, the armed tugboat Neptune and the Confederate Army cottonclad Bayou City. The two engaged with the largest of the Federal ships, the Harriet Lane, using their rams and guns. The Neptune was sunk, but the Bayou City continued its attack. Badly damaged, the Harriet Lane was boarded after its commander was killed and its second in command mortally wounded. The latter Union officer was discovered by his father, Confederate Major Albert M. Lea. Also found on the ship was the U.S. signal code book, a valuable acquisition.

With the battle going badly, the remaining Union ships fled to New Orleans, while the still-grounded flagship Westfield was blown up to prevent its capture. Even that went badly, as the Union fleet commander and part of his crew were killed when the charges went off prematurely. The departure of the Federal fleet was taken as a sign by Federal troops still ashore to surrender. The Confederate triumph in the six hour battle left Galveston in Southern hands until the end of the war.

Red River Campaign

The naval war on the Mississippi was pretty much finished in July 1863 but continued to the end of the war on the rivers that fed it.

One of the war’s most poorly conducted campaigns was the Federal Red River campaign of March 1864. While the official aim was to extinguish resistance in Louisiana and Texas, Admiral David Porter, who conducted naval operations on the river, later described it as “a big cotton raid” meant to seize some 100,000 bales of cotton from the Confederates. Some 90 Federal ships joined the expedition, the largest fleet ever assembled in North America at that point.

The plan was to send Union gunboats 350 miles up the river to Shreveport, with Federal troops led by Nathaniel Banks marching on land parallel to the fleet. Banks was a political general with no military experience – Porter was under the impression General Sherman would lead the land forces when he agreed to the campaign. Porter had little faith in Banks, who had already suggested he might abandon the fleet if he ran into trouble.

Launched on March 10, 1864, the campaign went well enough at first with the rebels pulling back ahead of the Union forces. The army reached the city of Alexandria eight days later, but without their commander. Banks arrived a week later on a ship full of cotton speculators with political connections in Washington. Porter was outraged.

However, the Union troops became confused in unfamiliar terrain, not even discovering the road that ran alongside the river. Confederates burned the cotton rather than allow it to fall into Federal hands, and started to mount successful counter-attacks.

Thirty miles from Shreveport, the tinclad fleet encountered a large steamboat blocking the river. It was as far as they would get, with Federal troops now fleeing back to their starting point in Alexandria. Rebel artillery and marksmen were able to deploy on the banks without opposition, keeping the tinclads under constant fire. To make matters worse, the river, which should have been rising at that time of year, was falling instead. The ships began to snag or run aground, requiring men to perform the hard labor of freeing them while under murderous fire. The strongest ship in the fleet, the USS Eastport, a former Confederate steamer captured by the Union and converted to an ironclad, struck a mine and had to be blown up to prevent its capture. Another steamer carrying slaves taken from plantations had a shell pierce her boiler, killing over 100 right away. 83 others were scalded so badly most of them died. The nightmare threatened to turn worse as it became apparent the fleet would be unable to cross the rapids at Alexandria due to low water. It looked like ships worth a total of $2 million would have to be abandoned and destroyed.

The USS Lexington Crosses the Dam and Rapids at Alexandria, Louisiana

The USS Lexington Crosses the Dam and Rapids at Alexandria, Louisiana

At this point, a Wisconsin engineer, Colonel Joseph Bailey, employed thousands of men, many of them timbermen from Wisconsin and Maine, to work on a massive dam across the 758-foot wide river, using lumber, bricks and even the machinery from a demolished sugar mill. After ten days, the water had risen high enough to allow four ships to shoot the rapids, but others could not make it. Another three days of dam construction finally allowed the rest of the fleet to escape total destruction. It was a brilliant piece of engineering in the midst of an otherwise disastrous campaign that cost more than 5000 Federal lives.

Nonetheless, the campaign was judged a disaster. Porter declared he never wished to command a river fleet again and was transferred to the Atlantic blockade. The ambitious Banks lost any hope of running for the presidency and spent the rest of the war testifying about his own incompetence in front of Congress.

Final Run of the CSS William Webb

For the last major Confederate naval action on the Mississippi, a wooden sidewheeler privateer converted to a cottonclad ram by Colonel Lovell was armed with a bronze 130-pounder James rifle on its forecastle and two 12-pounder howitzers. The James rifle was the largest used on any of the river warships, weighing 14,896 pounds.

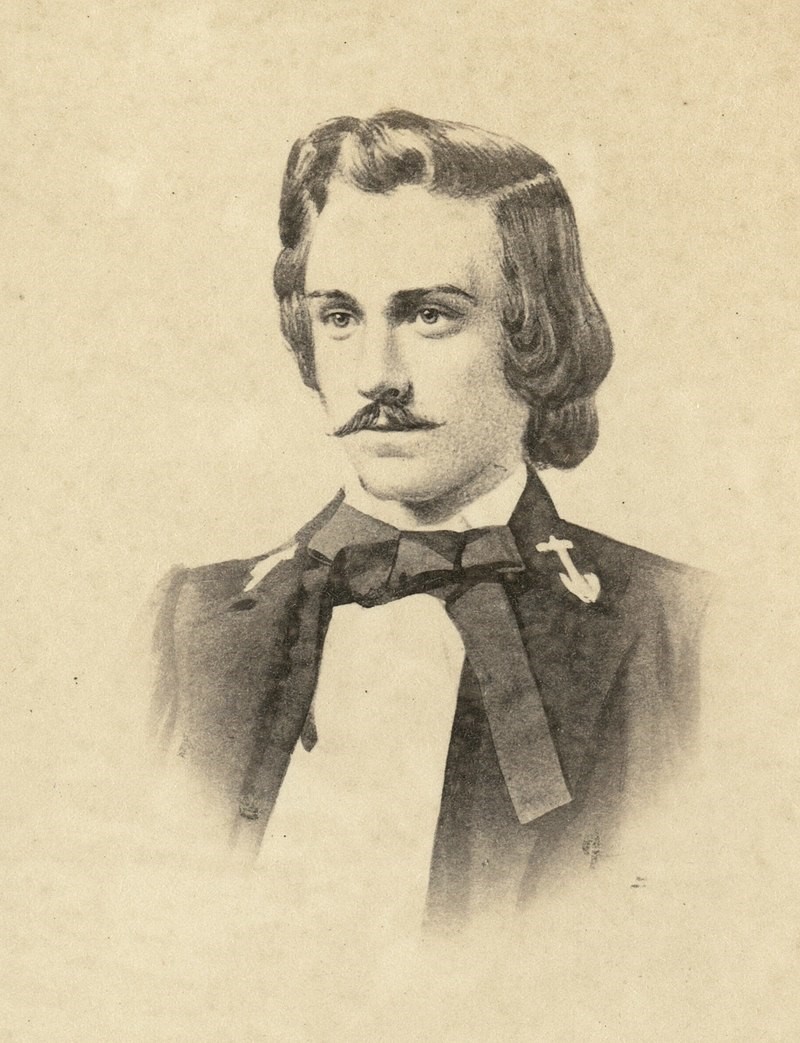

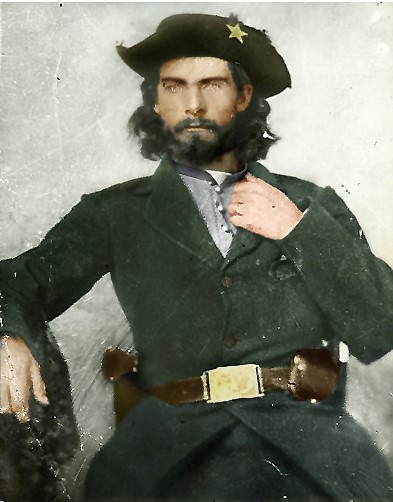

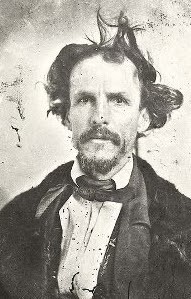

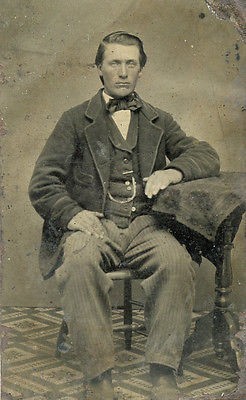

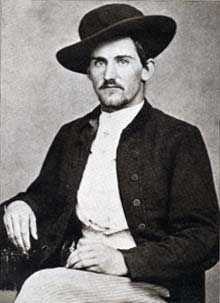

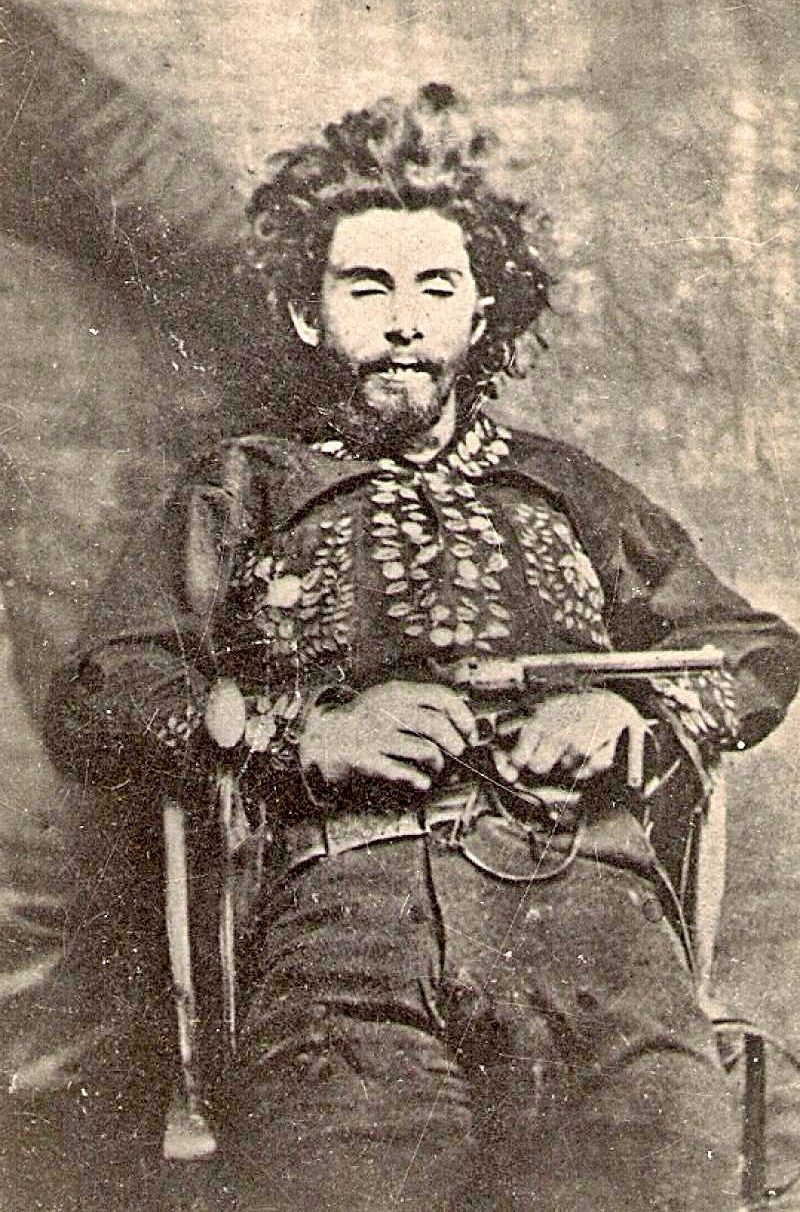

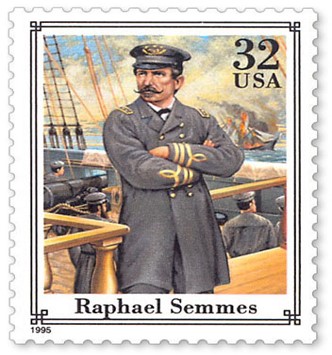

Lieutenant Charles “Savvy” Read, CSN

Taking command of the CSS William Webb was Lieutenant Charles “Savvy” Read, one of the naval war’s most outstanding characters. Bold and fearless, Read had graduated from the US Naval Academy only a year before the war broke out. Read served as an officer on Confederate commerce raiders such as the CSS MacRae and the CSS Florida, as well as serving on the Confederate ironclad Arkansas when it made its dramatic passage through the Union fleet on the Mississippi. Given command of one of the Florida’s prizes, Read raided the Atlantic coast, capturing or destroying 22 ships. Finally captured off Maine, he served time as a prisoner before being freed in an exchange. He then commanded several torpedo boats in the James River before taking command of the Webb in Shreveport.

On April 23, 1865, the Webb began a southwards dash from Shreveport, down the Red River to the Mississippi, where it broke through the blockade of the Red River. The Webb now made a run for the Gulf, with the intention of steaming out to the Pacific to raid Federal shipping there. Evading all kinds of Union warships, the Webb made it past New Orleans but was brought up short by the USS Richmond, a powerful steam sloop. Recognizing the stronger Richmond would easily destroy the Webb and her crew, Read ran the Webb aground and set her on fire. It was the last significant naval action of the war on the Mississippi and her tributaries.

Conclusion

With the war finally over in the spring of 1865, nearly all the converted river steamers were sold for scrap or returned to commercial use. The United States would never again fight a war on its rivers.

Ram warfare continued for some time, being an important part of naval architecture until the end of the 19th century, when it was finally realized by all that powerful new guns would fight naval battles at a distance. Several terrible accidents involving rams and other warships, and even a collision with a passenger ship that took over 500 lives, effectively put an end to the naval ram as an instrument of war.

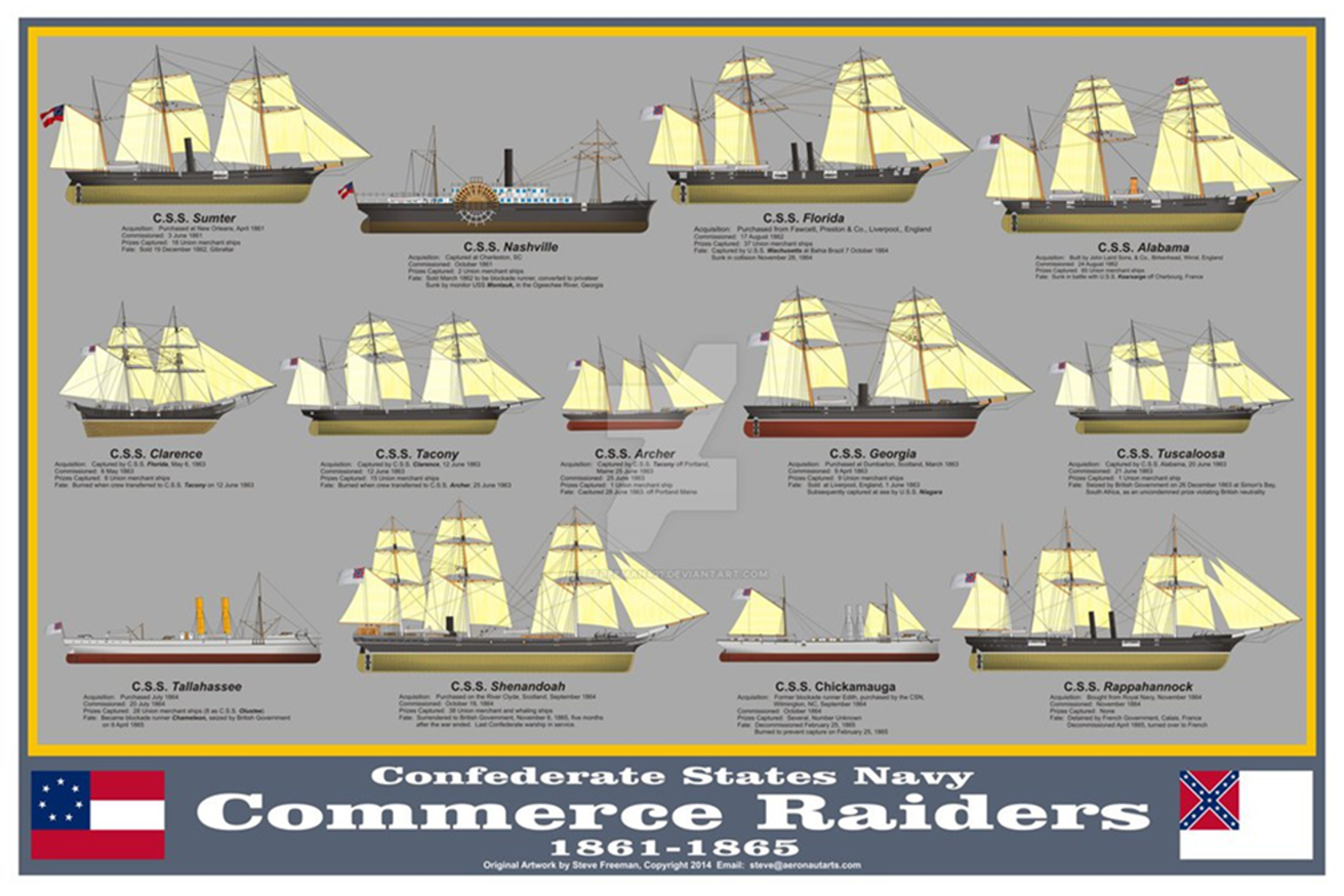

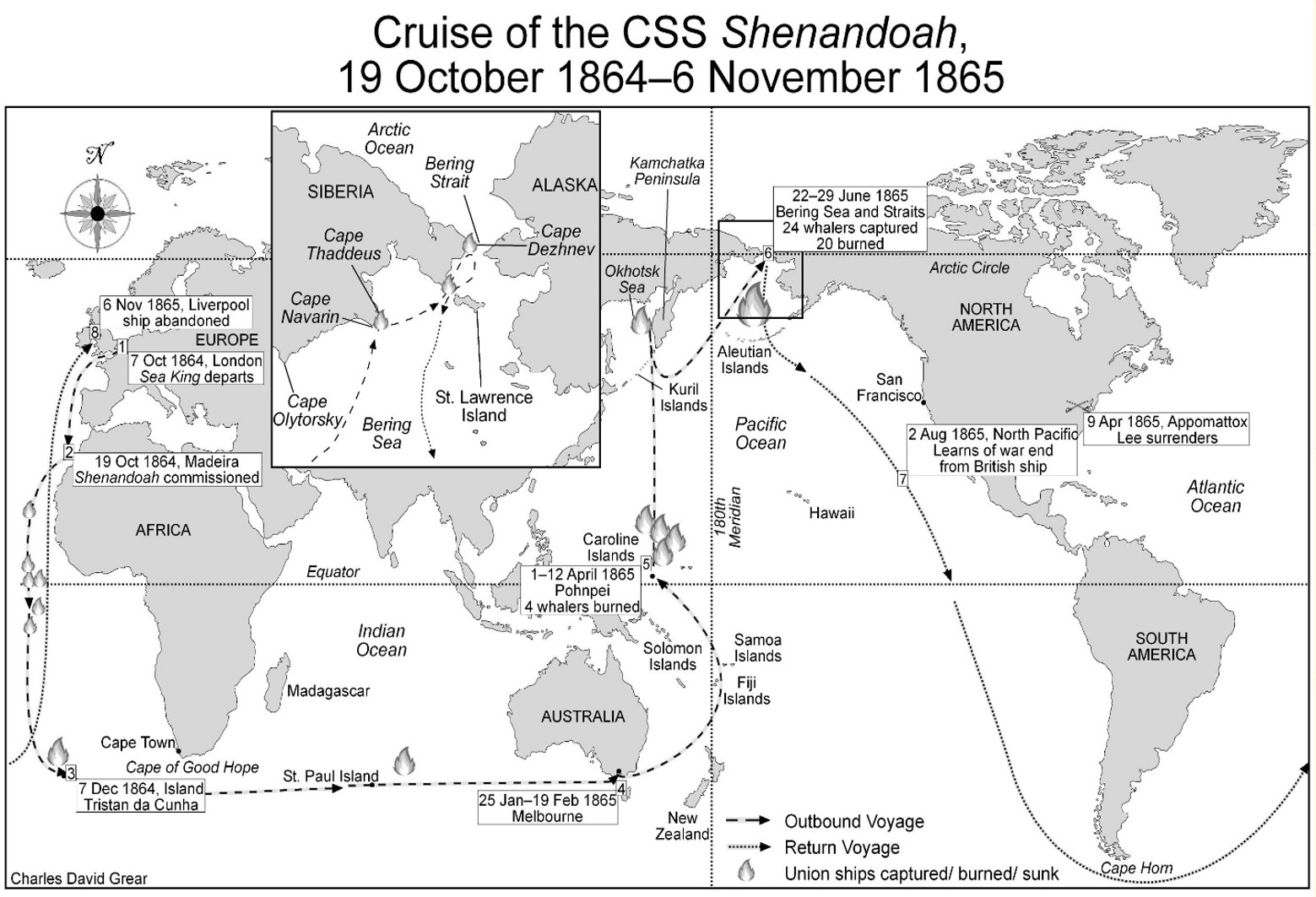

In conclusion then, we can say that there were more dramatic and romantic parts of the naval Civil War that inspired songs, paintings and poetry, episodes such as the global cruises of the Confederate commerce raiders, the battle between the Alabama and the Kearsage or the ground-breaking battle between the Virginia and the Monitor at Hampton Roads. Nonetheless, the hard and often relentless fighting done by these often ungainly, unsightly and quickly improvised Union steamships in the war’s Western theater played just as important a part in the war’s conclusion as the better known Union blockade by helping to split the Confederacy in two.

Bibliography

Coffey, Walter: “Confederates Confront the Indianola,” February 1, 2018, https://civilwarmonths.com/tag/c-s-s-william-h-webb/

Frazier, Donald S.: Cottonclads!: The Battle of Galveston and the Defense of the Texas Coast (Civil War Campaigns and Commanders Series), State House Press, Abilene, Texas, 1998

Joiner, Gary: One Damn Blunder from Beginning to End: The Red River Campaign of 1864, Scholarly Resources, 2003

Konstam, Angus: Mississippi River Gunboats of the American Civil War, 1861-65, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, 2002

McPherson, James M.: War on the Waters: The Union and Confederate Navies, 1861-1865, University of North Carolina Press, 2012

Miller, Francis Trevelyan: The Navies: The Photographic History of the Civil War, Castle Books, New York, 1957

Smith, Myron J. Jr.: The Timberclads in the Civil War: The Lexington, Conestoga and Tyler on the Western Waters, McFarland & Company, Jefferson NC, 2008

Smith, Myron J. Jr.: Tinclads in the Civil War: Union Light-Draught Gunboat Operations on Western Waters, 1862-1865, McFarland & Company, Jefferson NC, 2010

Van Doren Stern, Philip: The Confederate Navy: A Pictorial History, Bonanza Books, New York, 1962

Wideman, John C.: Naval Warfare: Courage and Combat on the Water, Civil War Chronicles, MetroBooks, New York, 1997