Andrew McGregor

A Talk given to the Civil War Roundtable, Royal Canadian Military Institute, Toronto on April 3, 2019.

Part One

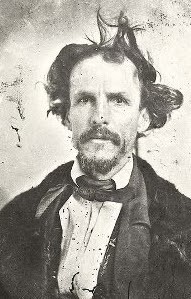

William “Bloody Bill” Anderson

William “Bloody Bill” Anderson

A low level conflict had already been raging in the Missouri-Kansas borderlands in the years preceding the outbreak of the Civil War. Fuelling this conflict was a dispute over whether Kansas should be a slave-holding state or not. By the time the war started, Missouri’s pro-rebel guerrillas were known as “Bushwackers,” while their pro-Federal counterparts in Kansas were known as “Jayhawkers” or “Redlegs” from their preference for red pants as a type of uniform. The Jayhawkers typically had access to Union arms and supplies while the guerrillas depended on foraging and the support of pro-secession families.

Early Anderson

Bill Anderson arrived in Kansas as a child in 1857 along with his Southern parents, two brothers and three sisters. When the war started, the 21-year-old Bill appeared to be running a business in stolen horses with his younger brother Jim. Soon Bill was mounting small raids into Missouri, though his devotion to the Confederate cause was questionable – he told a friend he was trying to recruit that he didn’t care anything about the South, but there was good money in bushwacking.

In May 1862, Bill and Jim took revenge on a man named Baxter who had killed their father in a dispute. Both Baxter and his 16-year-old brother-in-law were wounded by the Andersons, who then locked them in the cellar of their house and set it on fire. Baxter shot himself in the head to escape death in the flames, and the boy escaped through a window but soon died from his terrible injuries. It was the first public sign of the combination of vicious anger and callous regard for life that would characterize his short career as a guerrilla leader.

The War Begins

While it is possible that at least half the Missouri population were against secession, repressive measures by out-of-state Union forces turned many into reluctant supporters of the Southern cause. The activities of the Jayhawkers were even more counter-productive – Union General Henry Halleck complained that their outrages had done as much for the enemy in Missouri as could be done by 20,000 Confederate troops.

Senator Jim Lane, for example, led his Jayhawkers into Missouri in September 1861. There they burned down the entire town of Osceola and executed nine male civilians. Lane became known as the “Grim Chieftain.”

Halleck issued an order in March 1862 that declared the Confederate guerrillas to be outlaws subject to summary execution. The guerrillas responded with a policy of no quarter, and black flags began to appear in the rebel ranks. A further order forcing the conscription of all able-bodied men into Union militias convinced many young men in Missouri to join the guerrillas instead. Still, some 52,000 recruits of questionable value and loyalties were impressed into the Union ranks.

Both Confederate president Jefferson Davis and his Secretary of War Judah Benjamin were opposed to the existence of guerrilla bands outside government control, but with ever larger parts of the Confederacy passing beyond the control of regular forces, the guerrillas presented a lone if distasteful alternative.

Pea Ridge

After some initial Confederate victories in Missouri, Confederate forces under General Earl Van Dorn were defeated at the two-day Battle of Pea Ridge. The rebel army was driven south into Arkansas and would not return to Missouri for over two years. This left the field open to independent guerrilla commanders who took little if any direction from Confederate authorities.

Quantrill

In the Fall of 1862, Bill and Jim ran afoul of guerrilla leader William Quantrill, who took their horses as punishment for robbing Southern sympathizers as well as pro-Unionists. In May 1863 the brothers discovered their family home was nothing more than charred ruins, courtesy of the Kansas Jayhawkers.

Anderson joined Quantrill’s guerrillas. A school teacher from Ohio, Quantrill became one of the most notorious figures of the US Civil War. Beginning with a small group of men fighting the pre-war Kansas Jayhawkers, Quantrill eventually came to lead hundreds of guerrillas. Though it is a matter of some dispute, Quantrill may have held a Confederate commission as a captain of partisan rangers. His guerrillas certainly did not operate in the same way as the commands of partisan rangers such as John Singleton Mosby and John Hunt Morgan, which were much more tightly integrated with the CSA.

In late 1862, the Union ordered the imprisonment of all women known to be related to the guerrillas. Bill’s 16, 14, and 12-year-old sisters were imprisoned upstairs in a 3-storey building in Kansas City. After Union troops removed the supports for the building’s central girder on the main floor, leading to the building’s collapse and the death of four women, including one of Anderson’s sisters. His other two sisters suffered crippling injuries and disfigurement.

Quantrill’s outraged band blamed the federal troops. Anderson was beside himself with anger and now became dedicated to a single purpose; the killing of as many Union soldiers as possible. If this could be done while inflicting fear and pain, all the better. The aims and reputation of the Confederacy would henceforth play little if any role in determining his strategy and tactics.

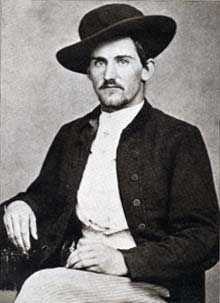

John Noland, Quantrill’s Chief Scout

John Noland, Quantrill’s Chief Scout

Quantrill and his followers decided that revenge would be had for the girls’ deaths, and the location would be the Kansas town of Lawrence, an abolitionist hotbed and home to Jayhawker Senator James Lane, who had led the raid on Osceola. A reconnaissance of the town was done by John Noland, a black Confederate and one of Quantrill’s most trusted scouts. Noland was one of five known Black Americans who rode with the Missouri bushwackers.

The guerrillas rode into Lawrence on August 21, 1863, shouting “Remember Osceola.” Over 200 civilian men and boys were killed in four hours. Anderson was seen coolly killing fourteen men even as they begged for mercy. “I’m here for revenge,” said Anderson, “and I have got it.”

The Union responded to the Lawrence massacre by driving away the population of three Missouri counties and allowing Jennison’s Redlegs to torch everything left.

Lieutenants and Allies of Bloody Bill

By July 1863 Anderson had entered the historical record of the war as commander of a group of 30 to 40 guerrillas. Let’s have a look at some of his allies and lieutenants, keeping in mind the very fluid organization and command structure of the guerrilla bands.

Todd was born in Montreal and was probably the only Canadian amongst the guerrillas. A man of action, it was said that Quantrill planned, but Todd executed.

Though he was described by various sources as being crude, illiterate, hot tempered, callously brutal, a deadly shot, and uncontrollable when drunk, his personal bravery and thirst for action were unquestionable. He was wounded nine times before his death and was described as “a maniac in battle.” Todd wrested control of Quantrill’s band in the spring of 1864 before allying himself with Anderson. He eventually died leading a charge while attached to General Price’s forces in 1864.

Dave Poole was one of Quantrill’s lieutenants and seems to have thought of himself as quite witty. Once he and his men caught nine Union soldiers in a schoolhouse and killed them. Poole propped the bodies up and “instructed” them at the chalkboard for an hour before complimenting them on their close attention. When Todd died in 1864, Poole took over his command.

Here we have teen-aged Archie Clements. 130 pounds and five feet of perpetually grinning malevolence, Clements was once described as Bloody Bill’s “chief devil.” Clements’ family home had been burned down and his brother murdered by Union militia, leaving Archie with a thirst for Union blood. He delighted in taking scalps and slitting throats.

Frank James was an early member of Quantrill’s band. Jesse, at sixteen, later joined Anderson’s band when Frank was still riding with Bloody Bill. The James Brothers, needless to say, used the skills they acquired as bushwackers to become two of the most famous American outlaws in the post-war period.

Guerrilla Weapons and Tactics

A common trait of the guerillas was a distaste for discipline. Most had never joined the army, were paroled prisoners or even deserters. Discipline was light but failure to turn up for an operation could mean death.

Colt Navy .36 cal., 1861 pattern.

Colt Navy .36 cal., 1861 pattern.

As mounted fighters, the guerrillas shared General John Hunt Morgan’s opinion that sabers were “as useless as a fence post.” The guerillas’ weapon of choice was the Colt Navy .36 cal., either in the 1851 or 1861 pattern. The Navy Colt was lighter than the Army Colt and thus preferable to men trying to carry as many as three to six at a time, which provided them with enormous firepower in battle.

Revolvers used in close provided overwhelming firepower in any clash with Union troops and the guerrillas carried as many as six each. Pre-loaded six-shot cylinders were carried in the pockets of their guerrilla shirts, allowing the guerrillas to quickly reload their weapons by swapping out the empty cylinders for full ones. The weapon of choice was the .36 caliber Navy Colt, favored over the heavier Army Colt. Their favorite long-arm was the breech-loading 1859 Sharps rifle, easy to handle on horseback, especially in its carbine version. The Sharps were large bore single shot rifles with a reputation for long-range accuracy. By 1863 both the guerrillas and the Union cavalry were carrying this weapon. The popularity of the weapons made it an icon of the “Old West” before production stopped in 1881.

Sawed-off shotguns were also in use and the personal arsenal was usually completed with Bowie knives and tomahawks for hand-to-hand fighting.

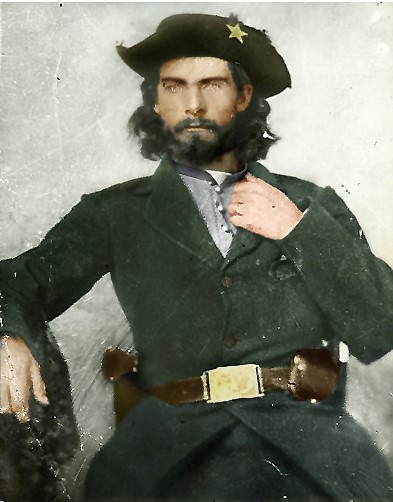

Guerrilla Shirt – Connections to Home

The guerrillas did not have access to Confederate uniforms, but in any case preferred to wear captured Union uniforms, which allowed them to confuse Union pickets and get close to their enemy, where their rapid-firing revolvers made the difference against muzzle-loading rifled muskets. When not wearing Union blue, the well-dressed guerrilla sported a slouch hat with a jaunty feather or squirrel tail, knee-high riding boots and the ubiquitous “guerrilla shirt.” Like the guerrillas’ long hair, the durable pullover shirt with its large pockets was a borrowing from the Great Plains hunters, who in turn had borrowed much of their style from the native Indians.

The Guerrilla Shirt: A Link to Home

The Guerrilla shirt could be “read” by anyone familiar with the code of different flowers, their arrangement and the color thread used for ornamentation. The shirt indicated the relationship the wearer had with its creator, mother, wife, sister or girlfriend and was a symbol of the important role women played in sustaining the guerrillas and nursing their wounds.

Missouri was known for the quality of its horses and the bushwackers always had better mounts than the indifferent nags and worn-out plow-horses sent to Union troops in a Civil War backwater like Missouri. This was a major factor in the guerrillas’ success in tying down large numbers of Union troops. For shelter, they would dig or find a cave in an inaccessible spot deep in the woods and conceal the entrance. Cooking was done only at night to avoid the smoke being seen and riders would enter or leave individually, each taking a different route and then reuniting at a pre-planned location. In winter, when concealment was difficult, the guerrillas would head south to Texas until the foliage returned in Missouri, though they did not leave drunkenness, mayhem and murder behind in their Texas sojourns.

The Charge

As the name “bushwacker” implies, the main tactic of the guerrillas was the ambush, sudden attack followed by a quick withdrawal and dispersal on fast mounts into country best known to the guerrillas.

At other times the guerrillas could make ferocious frontal attacks on Union infantry, the rapid fire of their revolvers dealing death and panic among troops armed only with slow-firing muskets and bayonets. Many witnesses described the guerrillas charging with reins between their teeth to enable revolver fire with both hands, but Frank James dismissed this in 1897 as “dime novel stuff… It was as important to hold the horse as it was to hold the pistol.”

Use of Terror

The bushwackers never missed a chance to enrich themselves through the war, robbing stagecoaches, trains, shops, storehouses and riverboats alike. Hand-in-hand with this was the terrorization of the civilian population by murder, torture and property destruction. Anderson’s reputation actually helped in recruitment; according to Jim Cummins, a member of Anderson’s band: “Having looked the situation over I determined to join the worst devil in the bunch, so I decided it was Anderson for me as I wanted to see the blood flow.”

Union supporters or relatives of soldiers could expect little mercy. Germans (who were called “Dutch” by the guerrillas) were routinely murdered by the bushwackers, who regarded all of them as Unionists. In one case, a German was found at the last moment before his hanging to actually be a Confederate supporter. Anderson simply replied: “Oh, string him up. God damn his little soul, he’s a Dutchman anyway.”

Bill offered some simple advice to the citizens of Missouri: “If you proclaim to be against the guerrillas I will kill you. I will hunt you down like wolves and murder you. You cannot escape.”

Counter-Measures

Union counter-measures included the death penalty for interfering with the railroads. Cutting the telegraph led to one captured guerrilla executed and the torching of every home within a ten-mile radius of the cut. With so many guerrillas wearing Union blue, federal troops relied on an elaborate and ever-changing system of hand signals and passwords to separate friend from foe, but Anderson and his lieutenants always appeared to be up to date on these signals.

In January 1864, Union authorities recognized that the actions of the Jayhawkers were ineffective in countering the guerrillas but exceptional in turning the people against the Union by their murder, looting and arson. They were replaced in January 1864 by the Second Colorado Cavalry which, unlike the Jayhawkers, were eager to come to grips with the guerrillas rather than just civilians.

Quantrill’s guerrillas spent the 1863-64 winter with the Confederate Army in Texas. However, as details of the Lawrence massacre seeped in, Quantrill and his unruly gang were increasingly treated with disdain by the CSA officers. They were glad to see Quantrill, Todd and Anderson head back north to Missouri in March 1864.

Quantrill’s band broke up in the spring of 1864 after the guerrilla leader backed down from a challenge from George Todd. Lacking any real authority from the Confederate Army, bushwacker chieftains relied on respect, charisma, courage and ferocity to hold their commands. Anderson set off on his own with 20 men in March 1864. Anderson’s biggest objection to Quantrill was that he wasn’t intent on killing enough Unionists. When Quantrill executed one of Anderson’s men for robbing and murdering a farmer, that was the last straw for Bloody Bill.

By 1864 most of the older guerrillas who fought for the Confederacy had died, gone home or joined the regular Confederate army. Most of the bands now consisted of reckless and ruthless teenagers with lots of violent energy but little judgement. Many were illiterate farm boys who followed whoever could provide them with revenge, adventure, whiskey and loot. Politics provided only a veneer of legitimacy for their violence and descent into depravity.

Angered by incidents of scalping by Kansas Jayhawkers, the guerrillas took it up themselves in the summer of 1864. None were more enthusiastic about the practice than always smiling Lil’ Archie Clements.

The Battle at Centralia

As Sterling Price began his last attempt to retake Missouri in September 1864, he encouraged the guerrillas to mount attacks on garrisons and disrupt communications. Anderson’s group performed well, cutting telegraph lines and striking the Union supply lines. A Union patrol caught up to a group of seven of Anderson’s men, killed them and scalped them. The guerrillas swore revenge, and took it on September 27, 1864 at the Missouri town of Centralia.

Arriving in the morning, the guerrillas looted the town, drinking all the whiskey they could find. A stagecoach rolled in and was promptly robbed before a train arrived. All the passengers were robbed and some murdered except for 25 unarmed Union soldiers. These men were stripped and Anderson made a small speech, letting them know “You are all to be killed and sent to hell.”

Anderson ordered Clements to “muster out” the naked prisoners. Clements opened fire on them and the rest of the bushwackers joined in. All were killed, save one sergeant, who spent several unhappy weeks as Anderson’s prisoner, the only one Bloody Bill was ever known to have taken.

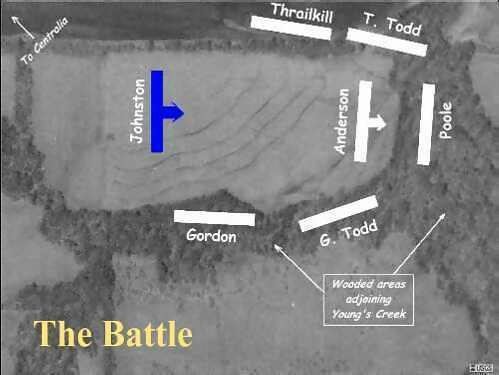

Deployments at the Battle of Centralia

Deployments at the Battle of Centralia

After Anderson left the town, he was pursued by a Union major, AVE Johnston, and 240 men of the 39th Missouri mounted infantry, a force roughly equal to the guerrillas. Johnston unwisely left half his force at Centralia to chase a small group of bushwackers led by Dave Poole, who led them into a large clearing in the midst of a forest. At the other end of the clearing were Anderson’s men, waiting by their horses. Unknown to Johnston, many more guerrillas lay in wait in the woods. The rifled muskets carried by the Union cavalry were unwieldy on horseback, so Johnston ordered his men to dismount and form a line, with a quarter of his force held back to hold the horses. As Anderson launched a furious charge, the Union volley went high. Before they could load again, Anderson’s men were among them with pistols blazing as scores of guerrillas poured out of the woods. Frank James later claimed his brother Jesse was the one to kill Major Johnston, but this is questionable – Jesse may not have even been there. On the other hand, Frank would later claim that he wasn’t there, admit that he was there, or say he was there but missed the events that followed as he was busy pursuing fleeing Union troops.

Most of the Union prisoners begged for their lives. After killing their captives execution-style but shots to the head, the guerrillas brought out their Bowie knives and tomahawks and spent the coming hours in what a witness described as a “carnival of blood,” dismembering, scalping, mutilating and decapitating their near-naked victims. It was considered good sport to switch the decapitated heads to different bodies or impale them on fence posts. The bodies lay so thick that Dave Poole amused himself counting them by jumping from body to body.

When the slaughter ended the guerrillas headed into Centralia to finish off the rest of Johnston’s command. The final death toll was three guerrillas to at least 116 Union dead. There were only two Union wounded, and these only survived the massacre because they had managed to flee,

The Centralia battlefield was excavated by archeologists, who published their report in 2008.

See Part Two at: https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4438