Andrew McGregor

A Talk given to the Civil War Roundtable, Royal Canadian Military Institute, Toronto on April 3, 2019.

For Part One of this talk, see: https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4425

General Price’s March Through Missouri

General Price’s March Through Missouri

Price’s Failed Campaign

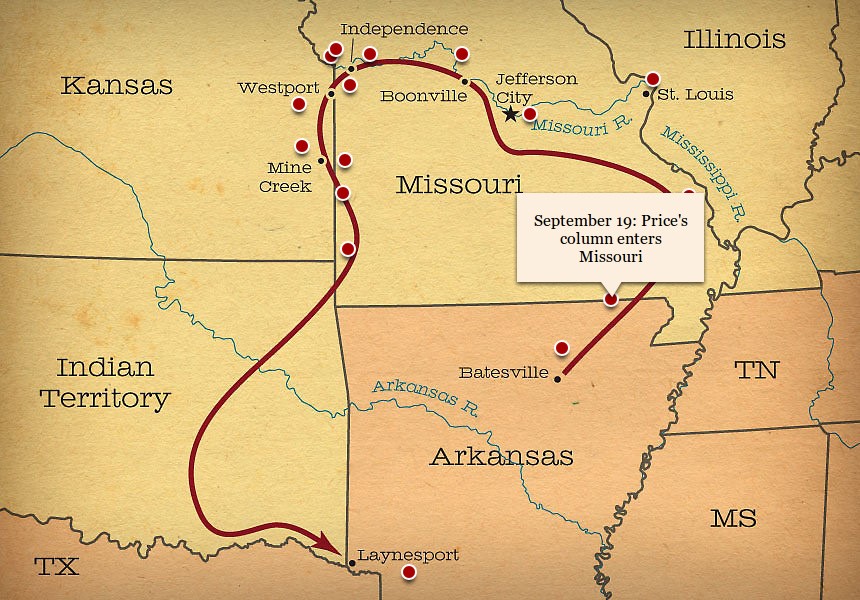

General Sterling Price led the last Confederate attempt to secure Missouri in September 1864. The plan was to take St. Louis, but it was too heavily defended. Instead Price began a meandering march in which he wasted his strength in a series of pointless battles. Price was strongly criticized by Jefferson Davis and others for his misuse of the guerrillas. Price sought to incorporate most of them into his column rather than dispersing them throughout the state to draw off Union troops.

Anderson’s command rode into General Price’s camp on October 11. Perhaps showing some detachment from reality, Bloody Bill rode up to Price and Governor Reynolds with scalps hanging from his saddle. The general and governor both erupted with rage at the display and told Anderson the CSA would have nothing to do with his band until all scalps disappeared.

Price and Anderson met again later that day. Instead of dismissing Anderson and his wild bushwackers, Price, desperate for support, issued a written order to “Captain Anderson” to destroy the North Mississippi Railroad. Bill gave Price a stolen set of fine pistols, which the general accepted.

Westport – October 23, 1864

Largely relieved from having to pursue guerrillas by Price’s choice to attach them to his force, Union troops were able to concentrate in a force much stronger than Price’s at Westport. By this time, discipline had broken down in Price’s army and the expedition increasingly occupied itself with looting, murder and rape, especially of German women.

The battle at Westport was the turning point of the campaign, with Price’s Army of Missouri badly defeated. The general was chased into Indian Territory, and by the time he returned to Arkansas he had only half the 12,000 men he had started with.

The Last Days of Bloody Bill

Bloody Bill’s reign of terror came to an end on October 27, 1864 at Albany Missouri. Lieutenant Colonel Samuel P. Cox had been assigned the task of eliminating Anderson. As one of the few regular officers to bother studying guerrilla tactics, Cox was the man for the job and was given men experienced in fighting bushwackers. Anderson, typically, decided direct action was appropriate. He led a charge expecting results similar to those at Centralia, but the veteran Union troops laid down a withering fire that brought the charge to a halt at 100 yards distance. Only two riders continued, plunging hell for leather through the Union line, but the troops turned round and brought both men down dead. One of these men was Bloody Bill.

Bill’s grey mare was found adorned with Union scalps. On his person was a letter from his wife with locks of hair belonging to her and their child, $600 in gold and greenbacks, $15 in Confederate script, a small Confederate flag presented to him by a friend, and Price’s written order to “Captain Anderson.” There was also a silk cord to which Bill was said to add one knot for every man he killed by his own hands. The cord had 53 knots.

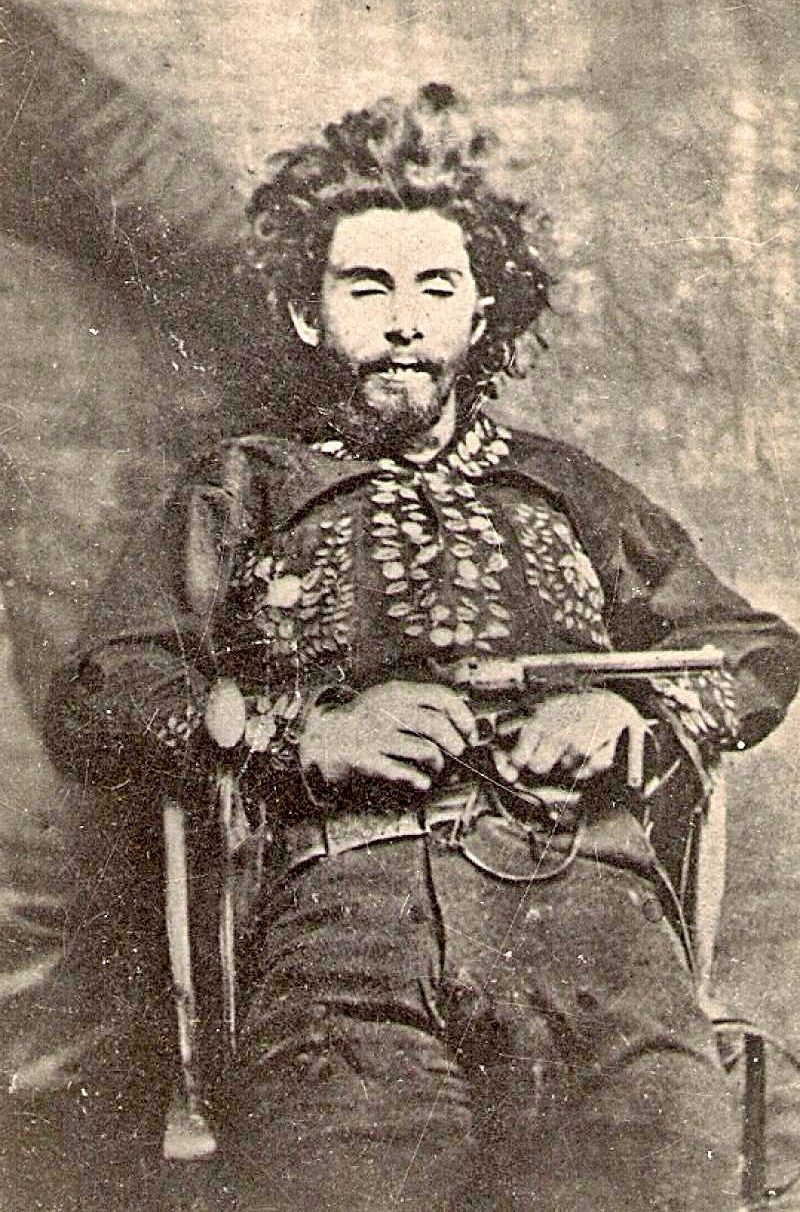

Bloody Bill Anderson in Death, Still Wearing a Guerrilla Shirt

Bloody Bill Anderson in Death, Still Wearing a Guerrilla Shirt

Shortly before his death, Bloody Bill announced, “I have killed Union soldiers until I have got sick of killing them.” Most of the Missouri population was sick of Bloody Bill as well; as a local newspaper proclaimed, “An avenging God has permitted bullets fired from Federal muskets to pierce his head, and the inhuman butcher of Centralia sleeps his last sleep.” (St. Joseph Morning Herald).

Anderson’s Grave

Cox put Bloody Bill’s body on display in Richmond Missouri. Hundreds of people lined up to see it. The local dentist, who doubled as the town photographer, was summoned to take two shots of Anderson’s corpse propped up in a chair. Both photos show that his left ring finger has been cut off, likely to retrieve his ring. After the photo-op, Anderson was decapitated and his head stuck on a telegraph pole. The rest of his body was dragged through the streets. The remains were eventually gathered and placed in a shallow grave.

Jennison’s Jayhawkers later became enraged when they saw his grave in Richmond covered in flowers. Never having the nerve to face him in life they destroyed what they could with their horses and finished by urinating on what was left.

After a local request, the US government provided a new headstone for Anderson’s grave in 1969.

What Happened to Anderson’s Band?

Various experiments in counter-insurgency strategies failed to drive the guerrillas from the field by the end of the war. The ferocity and brutality of a conflict waged between neighbors and families precluded the possibility of an easy transition into a post-war peace. Murder, mutilation, looting and arson were not quickly forgotten crimes and there was little chance they could be considered as simply the fortunes of war. While some guerrillas attempted to start new lives, others had developed a taste for theft and butchery that could not be sated in peace-time.

At the war’s end, many of the guerrillas surrendered after receiving assurances they would not be hanged by the army but would still be subject to civil prosecution. The Kansas City Journal proposed that the bushwackers should be “decently treated, decently tried, decently convicted and decently hung.”

Some, like Lil’ Archie Clements, were unable to obtain favorable conditions and thus remained under arms. Many had no homes left to go to, and there was always the danger of being waylaid by vigilantes. Some of the guerrillas were unwilling to live under Union occupation and joined General Jo Shelby’s brigade as they crossed into Mexico to offer their services to Emperor Maximillian.

Others, like the James brothers, the Younger brothers and the Shepherd brothers, found the transition into peacetime difficult, both because they enjoyed the bushwacking life, but also because they were forced to live in constant fear of arrest or lynching by vigilantes. As bushwackers they had learned how easily banks and trains could be robbed and the hard life of a farmer held little appeal by comparison. These men went on to epitomize the lawlessness of the “Wild West” and their post-war violence has been both glorified and villainized in popular culture ever since.

Of the Jayhawkers who had burned and murdered their way through Missouri without ever confronting the Confederate guerrillas, Dr. Charles Jennison was court-martialled in 1865 for looting western Missouri, while Jim Lane, who had narrowly avoided death in the Lawrence raid, shot himself in the head a year after the war ended.

After a last winter in Texas, Archie Clements, Dave Poole and Jim Anderson headed back up to Missouri. Clements was soon back to taking scalps and leading a band of as many as 100 men in a rampage of murder, arson and robbery even as the Confederate Army collapsed elsewhere.

With the war over, Clements began hanging out in Lexington saloons with Dave Poole, who was now robbing banks. There was a $300 reward on Archie’s head, but no-one had the nerve to try and collect. By late 1866 there was such an upsurge in violence in Missouri that all men of military age were again ordered to report for registration in the militia. As a joke, Clements, Poole and 25 heavily-armed former bushwackers rode into Lexington in military formation to report for militia duty. The garrison commander did not appreciate their humor but added their names to the roles as required and ordered them out of town.

Grave of “1st Lieutenant” Archie J. Clements

Grave of “1st Lieutenant” Archie J. Clements

Clements, however, returned to town to have a drink with a friend. A squad of militiamen was sent to arrest him, but Clements burst out of the saloon firing furiously. He mounted his horse and got part way down the street before falling prey to sharpshooters who lined the rooftops to prevent his escape. Clements was only 21-years-old when he died on December 13, 1866.

Bloody Bill’s brother Jim disappeared around 1867-68. He was killed either by Dave Poole’s brother William or by guerrilla George Shepherd, who was reported to have cut Jim Anderson’s throat on the courthouse lawn in Sherman Texas.

As for Quantrill, he was captured after being badly wounded and died in prison in June 1865. His body suffered numerous indignities, his bones were stolen, some put on exhibit, and his skull served duty for decades as a prop in a college fraternity’s initiation rites. Eventually his remains were collected though they still occupy two separate graves, one in Ohio and one in Missouri.

Confederates or Bandits?

In March 1864, General Price reportedly made Quantrill a colonel in the CSA in exchange for turning over a large number of his men to the army. As a result Todd became a captain and Anderson a lieutenant, but these ranks existed only within the unit and do not appear to have ever been commissioned officially by the CSA.

General Jo Shelby, a Missourian and one of the Confederacy’s best fighting generals, held a low opinion of the guerrillas: “They are Confederate soldiers in nothing save the name… No organization, no concentration, no discipline, no law, no anything.” Bloody Bill even denied “the name” part, stating: “I am a guerrilla. I have never belonged to the Confederate Army, nor do my men.” That was in July 1864, before Anderson accepted the October 11 1864 order from General Price’s staff addressed to “Captain Anderson.” While he did little about the contents, Anderson still carried it with him at his death 16 days later.

Anderson’s ally and sometime rival George Todd once told a captured Union officer that he was not a Confederate officer, but was a bushwacker, and “intended to follow bushwacking as long as he lived.”

Cultural Heritage

Bloody Bill, the guerrillas and the bloodshed along the Missouri Kansas border all became fodder for novels and films in the 20th century. Here we can see posters from some of these highly fictional films, Quantrill’s Raiders, Kansas Raiders, The Bushwackers, and The Outlaw Josey Wales, in which the 24-year-old Anderson was played by the 55-year-old John Russell.

This poster (Generale Quantrill: The Human Beast) is actually for an American movie called Dark Command, with Walter Pigeon playing “William Cantrell.” The film’s Italian distributors apparently felt Quantrill was more marketable, restoring his real name, making it the title and promoting him to General in the process.

This poster (Generale Quantrill: The Human Beast) is actually for an American movie called Dark Command, with Walter Pigeon playing “William Cantrell.” The film’s Italian distributors apparently felt Quantrill was more marketable, restoring his real name, making it the title and promoting him to General in the process.

A more recent film, Ride with the Devil, was a fictionalized version of Bloody Bill’s campaign that worked much harder than its predecessors to get details of the guerrilla’s style and tactics correct.

Reunion

The Old Guerrillas Gather Round a Portrait of Quantrill

The Old Guerrillas Gather Round a Portrait of Quantrill

As passions faded over the post-war decades, the Missouri guerrillas began to hold reunions in 1898 like other Confederate units. Familiar faces at these events included Cole Younger, Frank James and John Noland, Quantrill’s loyal Black-American scout. Thirty-two such reunions were held, with the image of William Quantrill adopted as a kind of icon for the veterans, who posed with his portrait and wore ribbons with his image.

Conclusion

For the mostly teenage gunmen of Missouri, the war was more a matter of personal rebellion than political rebellion. If we assess their significance in the conduct and the outcome of the war, the best we can say is that they drew off large numbers of troops that might have been used elsewhere. However, most of the soldiers fighting the guerrillas were young, inexperienced conscripts of the Missouri militia. One of the main units engaged against Anderson, the 17th Illinois Cavalry, was described by their commanding general as unreliable and “almost worthless,” so the idea that these second-rate troops might have made a difference elsewhere is very much open to question. Once the hardened Second Colorado Cavalry took the field against them in 1864, the guerrillas began to take significant losses.

If we look at success or failure in the bushwackers’ own terms, the situation is different. By the summer of 1863, it was obvious the war in the West was lost. From this point on, the guerrillas fought in their own interest, not the Confederacy’s. Their flag was the black flag of no quarter, not the Stars and Bars. Anderson kept his Confederate battle flag carefully folded amongst his personal effects, like a memory of an earlier time and purpose.

The surviving guerrillas might even have judged their campaign as a success in their own terms: Was bloody revenge dealt out to the Union troops and their supporters? Were they able to loot stores and rob civilians? Was there plenty of whiskey and hootin’ and hollerin’ and shootin’ things up? Did they enjoy the fear they saw in their victims’ eyes? Did the war give them license to ignore the laws of both man and God?

The answer is yes to all. By war’s end the guerrilla war in Missouri had descended into a kind of Confederate version of the Lord of the Flies in which teenagers and young men used revenge as justification for operating outside the laws of war and conventional morality. Some, like the veterans attending the bushwacker reunions under Quantrill’s vacant gaze, managed to adjust to post-war life. Others, like William Anderson, had already entered a dark abyss from which there was no return and no escape except death.

And that is the terrible truth of the story of Bloody Bill Anderson.

It should be noted that much of our knowledge of the guerrillas and their methods of warfare is based on memoirs and interviews provided by the guerrilla veterans. These rarely agree in details and are usually colored by the perceived legal, political or personal need for the veteran to present his story in a certain fashion, resulting in a variety of contradictory accounts. Many guerrilla leaders, like Quantrill, Anderson and Todd, did not survive the war to give their own views and recorded nothing of consequence when alive (other than Anderson’s three letters to newspapers). The very nature of warfare in Civil War Missouri, often unseen and unrecorded, has rendered it difficult to produce a definitive account of the guerrillas despite the best efforts of many highly competent historians. The speaker, an interested amateur in Civil War studies, has relied heavily on the following sources:

Barton, OS: Three Years with Quantrill: A True Story Told by His Scout, John McCorkle, Norman, Oklahoma, 1914

Beilein, Joseph M. Jr.: Bushwackers: Guerrilla Warfare, Manhood, and the Household in Civil War Missouri, Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio, 2016

Brownlee, Richard S.: Gray Ghosts of the Confederacy: Guerrilla Warfare in the West, 1861-1865

Castel, Albert: William Clarke Quantrill: His Life and Times, New York, 1962

Castel, Albert: General Sterling Price and the Civil War in the West, Baton Rouge, 1968

Castel Albert: “Quantrill’s Bushwackers: A Case Study in Guerrilla Warfare,” Winning and Losing in the Civil War: Essays and Stories (Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 1996), pp. 133-44.

Castel, Albert and Thomas Goodrich: Bloody Bill Anderson: The Short, Savage Life of a Civil War Guerrilla, Lawrence Kansas, 2006

Colton, Ray C.: The Civil War in the Western Territories, Norman, Oklahoma, 1959

Goodman, Thomas M., and Captain Harry A. Houston (ed.): A Thrilling Record, Founded on Facts and Observations Obtained During Ten Days’ Experience with Colonel William T. Anderson (the Notorious Guerrilla Chieftain), Des Moines, Iowa, 1868

Goodrich, Thomas: Black Flag: Guerrilla Warfare on the Western Border, 1861-1865, Indiana University Press, Bloomington Ill., 1995

Leslie, Edward E.: The Devil Knows How to Ride: The True Story of William Quantrill and His Confederate Raiders, New York, 1998

McLachlan, Sean: American Civil War Guerrilla Tactics, Oxford, 2009

Oates, Stephen B.: Confederate Cavalry West of the River, Austin (3rd ed.), 1995

Sutherland, Daniel E.: A Savage Conflict: The Decisive Role of Guerrillas in the American Civil War, Chapel Hill N.C., 2009

Thomas D. Thiessen, Douglas D. Scott and Steven J. Dasovich: “This Work of Fiends”: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives on the Confederate Guerrilla Actions at Centralia, Missouri, September 27, 1864, Lincoln Nebraska, March 2008, https://www.scribd.com/doc/267011623/doug-scott-report?secret_password=JA9mGQDVbs3Yvzd6ENoX#fullscreen&from_embed

Wood, Larry: The Civil War Story of Bloody Bill Anderson, Fort Worth, Texas, 2003

Younger, Thomas Coleman: The Story of Cole Younger by Himself, Provo Utah, 1903