Part One – Why is Chad’s New Intelligence Director a Fulani Warlord Convicted of War Crimes?

The answer involves Russian mercenaries, the battle-death of an African strongman and a struggle between Paris and Moscow for influence in Africa.

Dr. Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report, February 6, 2022

Introduction

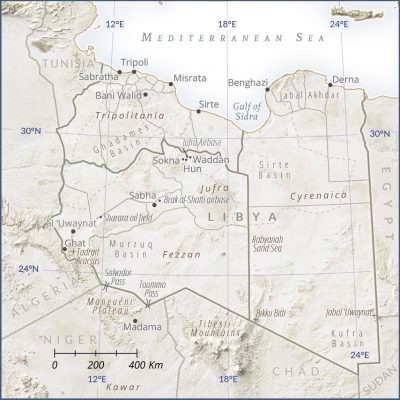

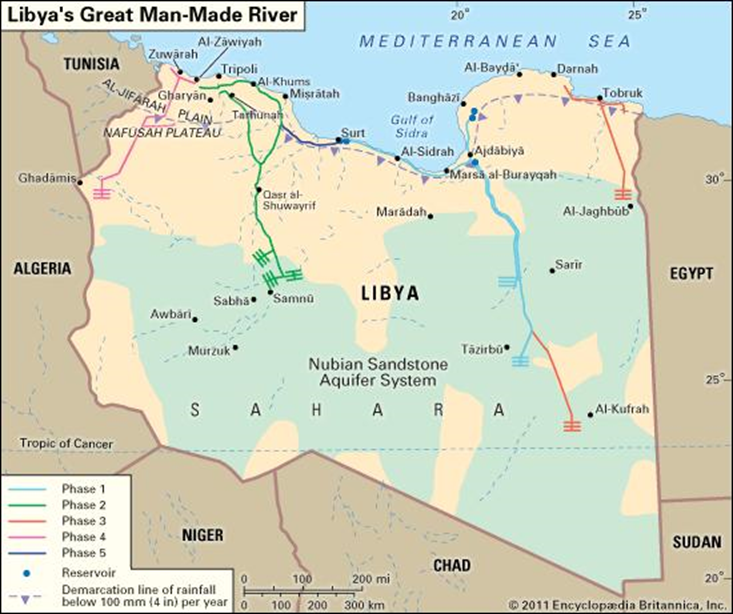

Chad and its southern neighbor, the Central African Republic (CAR), have been closely connected since the 18th and 19th centuries, when the old Muslim sultanates now incorporated into Chad treated the savannas and forests as a source of slaves and ivory. In the CAR, exploitation by the sultanates was followed by French colonial occupation and decades of post-independence misrule enabled by French neocolonialism, including the bizarre and bloody rule of “Emperor” Jean-Bédel Bokassa. The legacy of these destructive activities is that the CAR is one of the least developed countries in the world.

Despite this, the instability in the CAR attracts mercenaries, bandits and rebels, including many who straddle the line between these occupations. Chadians have long been prominent in these “trades” in the CAR but their influence has been challenged by the arrival of Russian mercenaries operating with the approval of the CAR government of President Faustin-Archange Touadéra. While the trade in slaves and ivory has passed, there are new possibilities in the land-locked nation for riches in diamonds, gold and other minerals, though development of the mining sector remains constrained by insecurity, high start-up costs, lack of transportation infrastructure and a local labor force familiar only with subsistence farming, herding and artisanal mining.

FACA Patrol at the CAR-Chad Border (Accueil)

FACA Patrol at the CAR-Chad Border (Accueil)

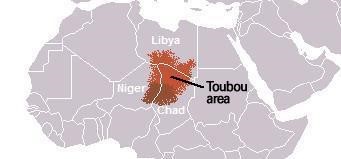

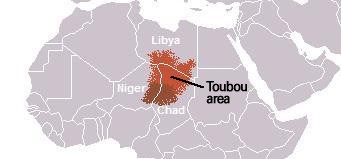

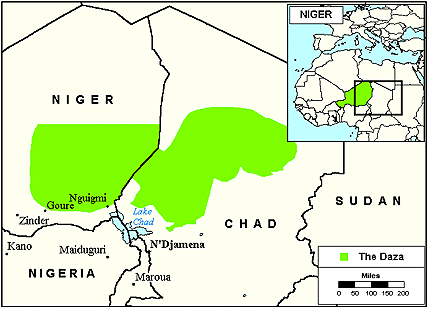

Both Chad and the CAR exist as a legacy of French colonialism, both incorporating a variety of ethnic groups inside borders drawn by the French and their colonial counterparts in Africa. One prominent group common to the borderlands between the two nations is the Fulani, an almost exclusively Muslim ethnic group that has spread across the Sahel. Comprised of an estimated 25 million people, many of the Fulani continue to follow a semi-nomadic lifestyle centered on herding cattle. [1] At a time when pressure on water resources and pastureland is increasing, the herders have come into conflict with agriculturalists dependent on the same resources. What was once a low-scale conflict has been greatly exacerbated by the influx of modern arms into the Sahel, with individual murders now replaced by massacres and cycles of brutal retaliation.

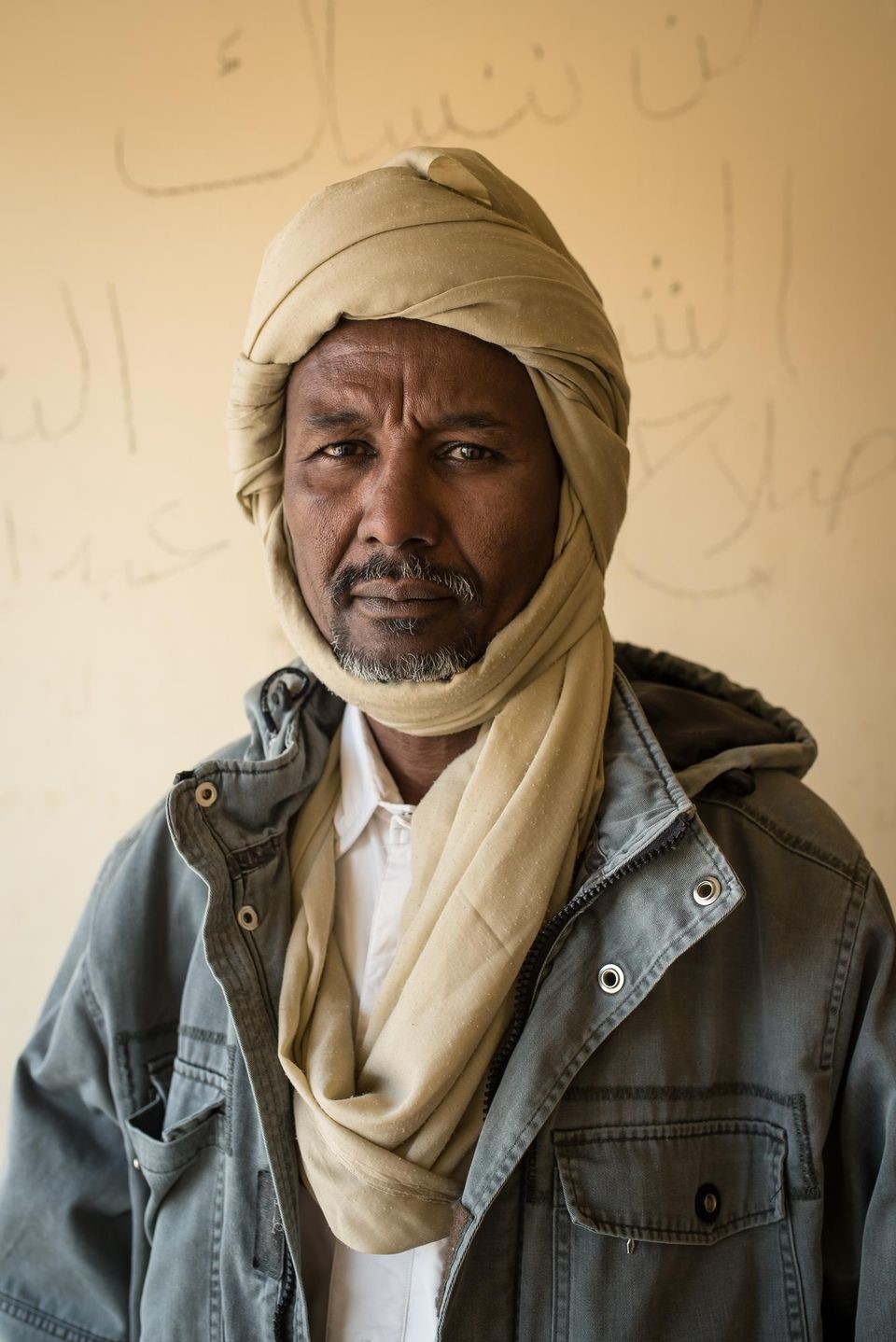

One individual who has tried to profit from the insecurity along the Chad/CAR border is “General” Mahamat Abdalkadar Oumar, better known by his nickname Baba Laddé (“father of the bush,” a Fula language term for a male lion). A warlord and highwayman (locally coupeur de route) with political pretensions, Baba Laddé now finds himself in the center of the border conflict and a larger struggle between traditional French influence and that of upstart Russian forces operating to the north of Chad in Libya, and south of Chad in the CAR. Baba Laddé belongs to the Mbororo (a.k.a. Wodaabe) branch of the Fulani, a nomadic sub-group of the Fulani best known for their adherence to Fulani customs and a traditional way of life focused on cattle-herding.

Having been sprung from a stretch of incarceration in some of Chad’s grimmest prisons, the 52-year-old Fulani warlord was appointed Chad’s new director of intelligence (officially Directeur général des renseignements généraux) on October 14, 2021. The general’s appointment indicates N’Djamena’s desire to focus on threats from its southern border, a region where troops of the Force Armée Centrafricaine (FACA – Armed Forces of Central Africa) carry out operations against Muslim rebel movements with support from Rwandan special forces and some 2,000 Russian mercenaries. When a variety of rebel movements joined forces in late 2020, they nearly succeeded in taking Bangui, the CAR capital. However, FACA’s foreign allies and troops of the UN peacekeeping mission in the CAR stopped the rebel offensive on the outskirts of Bangui on January 13, 2021. A government counter-offensive succeeded in driving most of the rebels back into the bush or across the border into Chad in the following months. Baba Laddé has support in his new role from the Fulani president of Nigeria, Muhammad Buhari.

The International Response to the Crisis in the CAR

In response to the communal violence sparked by the 2013 takeover of the CAR by Séléka (a coalition of Muslim rebel movements), France deployed troops in the CAR through Operation Sangaris from 2013 to 2016. The force was withdrawn amidst controversy over a UN report claiming sexual abuse of children by French troops (as well as African troops) and was replaced by a 15,000-strong United Nations peacekeeping mission, the Mission multidimensionnelle intégrée des Nations unies pour la stabilisation en Centrafrique (MINUSCA). At present, the UN mission consists solely of African and Asian peacekeeping contingents. These operate under a mandate to support the deployment of CAR security forces or to engage in joint operations with FACA designed to restore security. Complicating the relationship is the fact that FACA rarely moves out of its bases unless it is accompanied by Russian mercenaries or Rwandan Special Forces operating outside of any UN framework.

The French ended their military cooperation with the Touadéra regime in June 2021, but continue to run a logistics mission in Bangui and contribute military trainers to the European Union Training Mission (EUTM). Created in 2016, the EUTM’s mandate to provide military and ethical training to CAR troops has been renewed until November 12, 2022. MINUSCA does not conduct any military training.

The total number of personnel in MINUSCA, including soldiers, police, prison guards and civilians, is just over 19,000 in a mission that now costs over $1 billion per year (Le Quotidien [Dakar], January 19, 2022). Like its predecessors, the peacekeeping mission has been plagued by continuing allegations of sexual abuse of civilians. In mid-September, 2021, the entire Gabonese deployment was sent home after charges of sexual exploitation (UN News, December 11, 2021).

“Father of the Bush” – A Rebel Turns Regime Supporter

After 14 years of open rebellion to the regime of President Idriss Déby Itno of Chad, Baba Laddé surrendered in September 2012, but efforts at reintegration failed and he fled Chad for other parts of Africa before being persuaded to return in 2014. An archetypal African strongman, Idriss Déby (Bidayat/Zaghawa), chief-of-staff of the Chadian army, became president in 1990 after mounting a coup against his former patron, President Hissène Habré (Akanaza Tubu). Habré died of Covid-19 in August 2021 while serving a life sentence in Senegal for sadistic behavior and crimes against humanity that left as many as 40,000 dead during his presidency.

In July 2014, Baba Laddé was made prefect of Grande Sido, a department of Moyen-Chari province bordering the Central African Republic. The region was home to thousands of Muslim refugees from the CAR. Baba Laddé was dismissed in November 2014 when President Déby swept many governors out of office. Popular in Grande Sido, Baba Laddé used the confusion of local protests against his removal to escape a military convoy sent to arrest him on December 1, though his wife and bodyguard were severely beaten by enraged troops (RFI, December 3, 2014).

MINUSCA arrested the fugitive warlord a week later. Following the detention, his supporters demanded his release as a political refugee who feared for his life in Chad and should be given the opportunity of seeking political asylum elsewhere. In an open letter to MINUSCA, Shaykh Aboulanwar Djarma, opposition figure and former mayor of N’Djamena, expressed the opinion held by Baba Laddé’s friends:

If we cannot deny that some of Baba Laddé’s men have committed criminal acts, these were never ordered by Baba Laddé; on the contrary, he has always repressed those of his fighters who were perpetrators of such acts. The Chadian opposition has evidence of this, and several states also have in their possession evidence that exonerates Baba Laddé of criminal acts (Centrafrique-presse, December 12, 2014).

Nonetheless, MINUSCA sent Baba Laddé to Chad in January 2015, where he was confined in the notorious Koro Toro desert prison. The extradition marked a temporary end to Baba Laddé’s efforts to overthrow the governments of Chad and the CAR. Many of his fighters joined the recently formed Unité pour la paix en Centrafrique (UPC) rebel group, led by Baba Laddé’s former lieutenant, Ali Darassa Mahamat, a Fulani specialist in guerrilla tactics.

In early 2018, the still untried Baba Laddé became seriously ill in prison, but was not included in a general amnesty for former rebels in May 2018. In the same year, the UN Working Group on the Use of Mercenaries expressed concerns regarding human rights violations and long-term detentions without due process at the Koro Toro prison. [2] Finally convicted and found guilty of rape, arson, armed robbery, criminal conspiracy and illegal possession of weapons after nearly four years in detention without trial, Baba Laddé was sentenced to eight years in December 2018 (Tchadinfos, December 6, 2018).

Surprisingly, the warlord’s reconciliation with the Déby regime began before Idriss died on the battlefield. Baba Laddé’s sentence was commuted by the president on August 10, 2020 and he was freed the following September 7. It was a major shift in the late president’s interaction with Baba Laddé, whom he had previously described as nothing more than a highwayman. With rising tensions along the southern border with the CAR, Déby likely began to see the value in an asset with intimate knowledge of the border region and all those operating in it.

Still wary of the regime that had suddenly released him, Baba Laddé quickly left Chad. While living in Dakar after his release, Baba Laddé attempted to file papers for a run as candidate for the Front Populaire pour le Redressement (FPR) in the April 2021 presidential election, but was rejected by the Supreme Court of Chad on the grounds his party was not recognized. Laddé complained at the time that authorities sought to “criminalize” him by “wanting to create a rupture between the Popular Front for Recovery [FPR] and Chadian national opinion” (Jeune Afrique, March 11, 2021).

During the 2021 elections, Idriss announced his intention in March of doing something that still seemed unthinkable – bringing Baba Laddé back to Chad and into the fold of the regime. Shortly after this, Baba Laddé announced that he was abandoning the armed struggle against the Déby regime and would support the president’s re-election campaign: “I made the choice of peace. That’s what made me come back. Not just for Chad but for the sub-region… So, I came home, just to support [Déby] because he keeps the peace” (RFI, April 4, 2021).

In late January 2022, the members of Baba Laddé’s FPR gathered in Mandoul region (on Chad’s southern border with the CAR), sparking fears in some quarters that they intended to form a militia acting in parallel to the national army. The movement in turn announced that the FPR fighters were only assembling prior to demobilization or integration into the national army according to the terms of Baba Laddé’s agreement with former president Idriss Déby (Alwihda Info [N’Djamena], January 27, 2022).

Baba Laddé and the Fulani

Through convenience or in an effort to provide some political/ideological legitimacy to his armed movement, Baba Laddé has often posed as a defender of the Fulani people, though he has rarely expressed any type of ideology surrounding this standpoint.

In December 2011, Baba Laddé issued an open letter “to the People of Azawad” (northern Mali) that helped define his approach to the issues of the Fulani and their place in the ethno-political structure of the Sahel. Baba Laddé urged an alliance between the Fulani, the Tuareg, al-Qaeda, Ogaden separatists and the Saharan Polisario. He also expressed his support of Mali’s Songhay and Fulani-dominated Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso militias “because these people are afraid, afraid of being dominated, of being second-class citizens in an independent Azawad.” (Jeune Afrique, December 23, 2011). [3]

Baba Laddé, asserting that not all of Africa’s problems are due to European-imposed borders drawn without reference to local ethnic groups, suggested that federalism may provide a means of restoring the great multi-ethnic states of the past: “Let us remember the empires of Ghana, Mali, Songhai, Kanem-Bornu, the Almoravids. All of these pre-colonial states were multi-ethnic. There have always been states in Africa and they have always been multiethnic and that’s an abundance of wealth!”

Turning to the issue of violent clashes between Fulani herdsmen and agricultural communities across the Sahel, Baba Laddé offered a slogan rather than a solution: “Farmers and breeders must be united. In the Central African Republic, in Chad and in Azawad.” Though admitting al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) are ideologically in error, the Fulani warlord spoke sympathetically of their struggle: “Seeing the disastrous world where capitalism, perverse sexuality and corruption reign, they chose to destroy this world. Seventy years ago, they would have been communists, 110 years ago they would have been anarchists, in 2011 they are Salafi-Jihadists” (Centrafrique-presse, December 8, 2011).

In September 2021, Baba Laddé claimed to have been informed by a number of rebel movements in Mali that they would take up arms again if Russian mercenaries arrived in Mali, a decision based partly on what they had seen of the Russians in the CAR. The warlord called for a broad Fulani resistance to Russian expansion in the Sahel:

All the Central African communities are victims of the barbaric exactions of the Wagner mercenaries, but particularly the Muslims and even more particularly the Fulani civilians… We call on all Fulani, friends of the Fulani or more simply those attached to human rights to mobilize against Wagner… The fight is total against the Wagner mercenaries and the local allies of these barbarians (Corbeaunews, September 24, 2021).

There are many, however, who consider Baba Laddé’s ventures into ethnic politics a convenient cover for his illegal activities. The late Idriss Déby questioned Baba Laddé’s political credibility, insisting he was nothing more than “a former Chadian gendarme who became a coupeur de route [highwayman] and trafficker in ivory. He is not a rebel, as some media claim, but a great bandit. This kind of character does not constitute a threat to Chad. For the Central African Republic, maybe” (Vanguard [Lagos], December 6, 2021).

Death of a President

Even as president, Idriss Déby kept a tight rein on the military by remaining both a general and Chad’s defense minister. In these capacities he continued to take to the field to lead important operations in person, such as the March 2021 offensive against Boko Haram in the Lake Chad region. Déby’s presence there was required to bolster Chadian forces after a disastrous March 23 defeat of a garrison of largely inexperienced troops at the hands of Boko Haram on Lake Chad’s Bohoma Peninsula. One hundred Chadian troops were killed and 24 armored vehicles destroyed by the Bakura faction of Jama’at Ahl al-Sunnah li al-Da’wah wa’l-Jihad (the original faction of Boko Haram, led by Abubakar Shekau until his death in May 2021). The Bakura faction is led by a Nigerian, Ibrahim Bakura “Doron.”

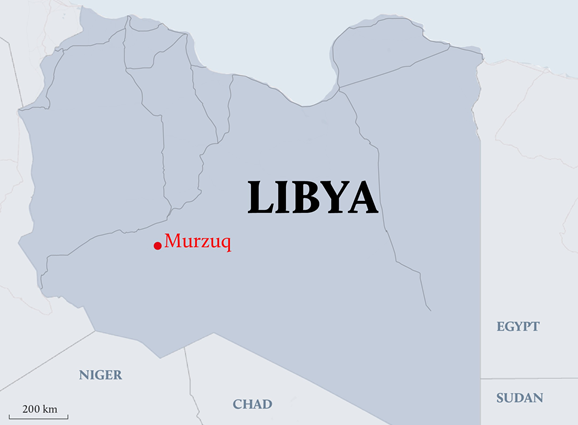

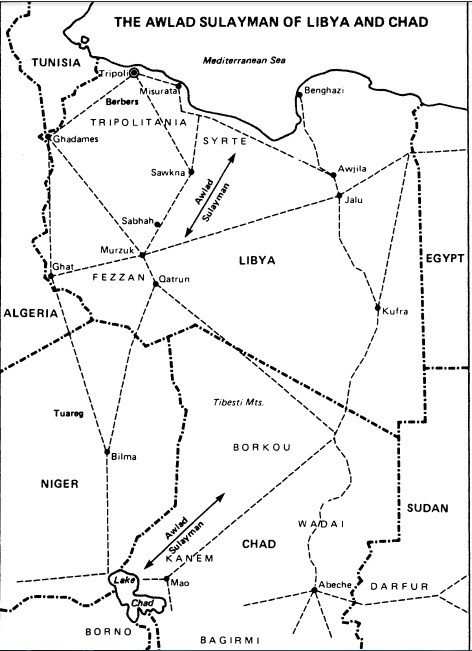

Only a few weeks later, President Déby’s rule was challenged from the north in the form of an offensive by the Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad (FACT – Front for Change and Concord in Chad), a Libyan-based movement of anti-Déby rebels from northern Chad. FACT was created by Mahamat Mahdi Ali in March 2016 and is dedicated to the overthrow of the Déby regime. Only one week after securing his election to another 5-year term, President Déby arrived at the frontline, but was mortally wounded by FACT rebels in the Kanem region of Chad on April 18, 2021. There was wide speculation that the FACT fighters were trained by Russian mercenaries in Libya (The Times [London], April 23, 2021; NYT, April 22, 2021; Foreign Policy, November 30, 2020). While confirmation was elusive, the claims were well-noted in N’Djamena.

Only a few weeks later, President Déby’s rule was challenged from the north in the form of an offensive by the Front pour l’alternance et la concorde au Tchad (FACT – Front for Change and Concord in Chad), a Libyan-based movement of anti-Déby rebels from northern Chad. FACT was created by Mahamat Mahdi Ali in March 2016 and is dedicated to the overthrow of the Déby regime. Only one week after securing his election to another 5-year term, President Déby arrived at the frontline, but was mortally wounded by FACT rebels in the Kanem region of Chad on April 18, 2021. There was wide speculation that the FACT fighters were trained by Russian mercenaries in Libya (The Times [London], April 23, 2021; NYT, April 22, 2021; Foreign Policy, November 30, 2020). While confirmation was elusive, the claims were well-noted in N’Djamena.

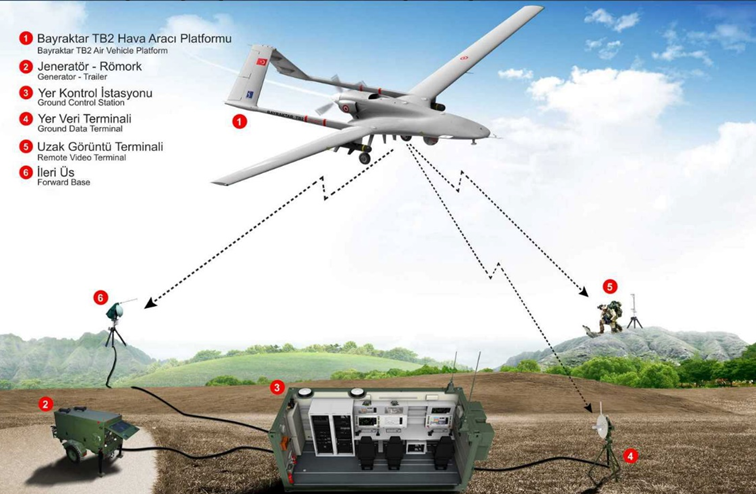

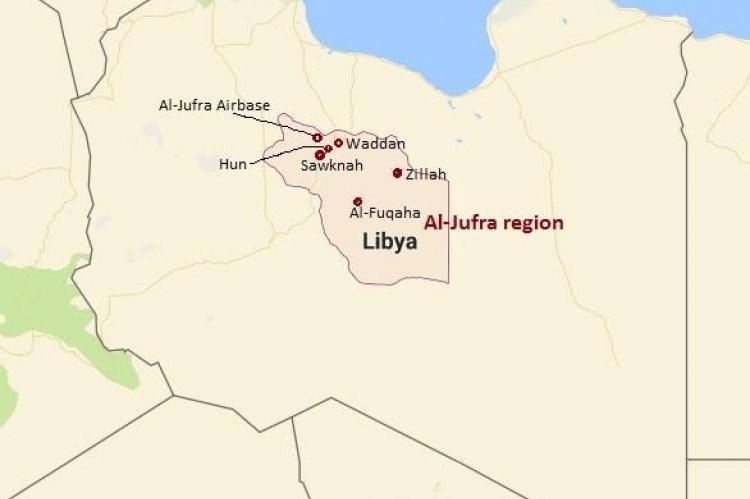

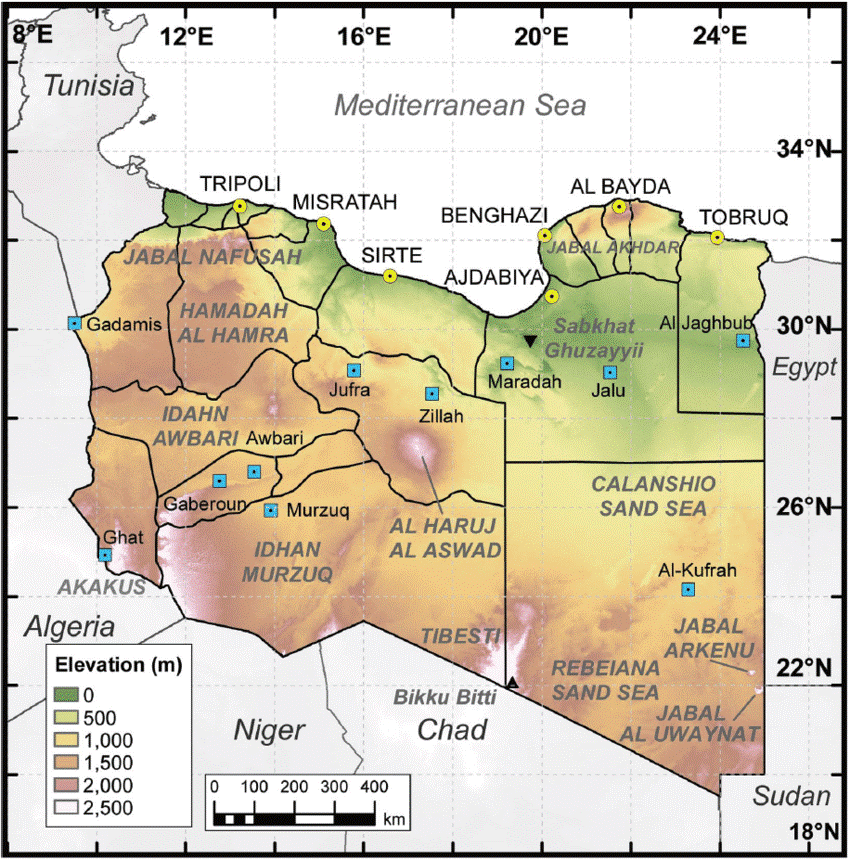

During their long stay in Libya, Chadian FACT fighters were employed as mercenaries by Russian-backed warlord Khalifa Haftar, leader of the so-called “Libyan National Army” (LNA). Backed by Egypt, the UAE and Russia, Hafter, a self-appointed “field marshal,” armed the Chadians and housed them at al-Jufra Airbase, the main base of the Russian Wagner Group mercenaries operating in Libya (Al-Araby, May 6, 2021). FACT’s association with the Russians was criticized by Baba Laddé: “FACT claims to want democracy. But Wagner will only ally with a rebellion if they are sure a dictator will take over and let them plunder the resources” (Corbeaunews, September 24, 2021).

In a bizarre incident, ten Russians were detained in June 2021 by Chadian police in a military operational zone in Kanem, close to where President Déby was killed in April. Though fighting in the region between Government troops and Libyan-based rebels had ceased only a month before, the Russians insisted they had organized a trip to a remote part of Chad because it “was very interesting” and “very rich in natural sites.” The wayward tourists, the apparent vanguard of a previously unknown Russian interest in touring “natural sites” in Chadian war-zones, were escorted to N’Djamena “for their own safety” and flown back to Moscow (Reuters, June 25, 2021).

A Family Dynasty in Chad?

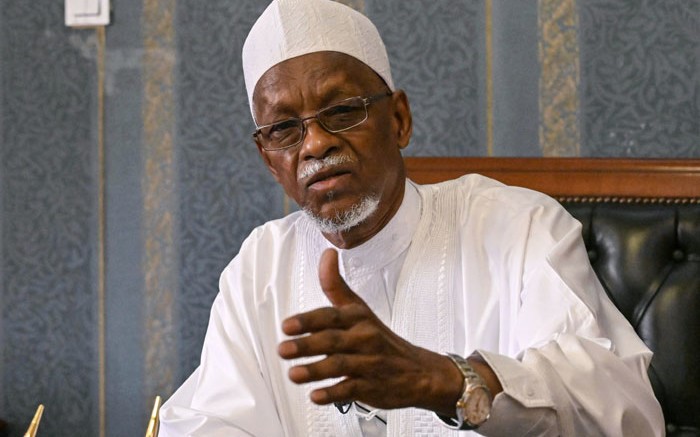

With the quiet support of Paris, the late president’s son and commander of the presidential guard, Mahamat Idriss Déby “Kaka” (Zaghawa/Gura’an Tubu) seized power in N’Djamena with a group of loyal officers, citing “extraordinary circumstances” that necessitated defiance of the CAR Constitution, according to which the President of the National Assembly would become temporary head-of-state until early democratic elections could be organized. [3] According to Mahamat Idriss, the president of the national assembly “refused to take office and no one could force him to become the head of state against his will. You are free to ask him about this” (Africa Report, June 30, 2021).

CMT President Mahamat Idriss Deby (Vincent Fournier for Jeune Afrique).

CMT President Mahamat Idriss Deby (Vincent Fournier for Jeune Afrique).

Mahamat dissolved the legislature, replacing it with a Conseil Militaire de Transition (CMT -Transitional Military Council) with himself as president that would oversee the nation until elections in 18-months’ time. Since then, the CMT has begun pressing for a five-year transition period.

Chad’s leaders often have connections through marriage to leading figures in neighboring Darfur and the CAR; Mahamat is married to the daughter of Abakar Sabone, a spokesman for the CPC rebel coalition and former advisor to Séléka leader and former CAR president Michel Am-Nondokro Djotodia.

Abdelkerim Idriss Déby, half-brother to Mahamat, graduated from West Point in 2014. He became hugely influential in the administration and was the man to talk to for investments and project approvals under his father’s rule. He continues to play this role in the CMT and works closely with Mahamat.

Mahamat Idriss also has the support of powerful figures such as General Daoud Yaya Brahim, the CMT’s defense minister, and General Bichara Issa Djadallah, a Rizayqi Arab, chief-of-staff under Idriss Déby and cousin of Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemeti” (the number two man in the Sudanese military junta). Another Déby family loyalist in the CMT is General Taher Erda, a Zaghawa and the new commander of the presidential guard. Loyal to Idriss since 1989, he is related to veteran Zaghawa rebels and twin brothers Tom and Timan Erdimi. In the often-small world of Chadian politics, the Erdimis are cousins of Mahamat Idriss. Timan is the leader in Qatari exile of the Chadian rebel Union des Forces de Résistance (UFR). Tom disappeared in late 2020 while staying in Egypt, but was discovered alive this month in Egypt’s notorious Tura prison (south of Cairo) by a relative accompanying a visit by Mahamat Idriss to the Egyptian capital (RFI, January 18, 2022). [5] Steps are being taken to obtain his release.

Chad is unaccustomed to worrying about a threat from the southeast, where the region that now forms the CAR was an established source of slaves, ivory and other resources for Chad’s Muslims and the Arab and African tribes of Darfur. Now facing an assertive military alliance of CAR regulars, Rwandan Special Forces and Russian mercenaries, Chad’s CMT would like to avoid threats from the southeast while it keeps forces available for regional counter-terrorism commitments and to protect Chad’s northern border from further incursions by rebel forces, especially those suspected of having some degree of training or support from Russian contractors. [6] Regarding the presence of Russian “Wagner Group” mercenaries in the CAR, Chad’s foreign minister, Cherif Mahamat Zene, stated: “external interference, wherever it comes from, poses a very serious problem for the stability and security of my country… There are Russian mercenaries present in Libya, who are also present in the Central African Republic” (UN/AFP, September 24, 2021).

The Wagner Group is a firm of private military contractors (PMCs) established in 2014 by Dimitri Utkin, a Special Forces and GRU veteran of the First and Second Chechen Wars (where his call sign was “Wagner”), though the outfit is believed to be owned by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a leading Russian businessman and Kremlin insider with close connections to President Putin. The company, together with several other Russian PMCs, provides openings for Russian political and economic influence in various conflict zones while providing deniability for the Kremlin, which routinely disavows any knowledge of their activities. Besides the CAR, the Wagner Group operates in Syria, Ukraine, Libya, Mozambique, Madagascar and Sudan; it has recently been engaged by Mali’s new military government. Burkina Faso might be next; the new ruling military junta there is headed by Lieutenant Colonel Paul Henri Sandaogo Damiba, who was previously unsuccessful in persuading the nation’s former civilian government to allow the entry of Russian mercenaries to combat Islamist extremists.

Chad’s foreign minister added that the May 30 attack border on a Chadian village near the CAR border was “backed” by Russian mercenaries and also claimed that the FACT rebels who killed President Idriss in April were trained by the Wagner Group (AFP, September 24, 2021). Though not referring to Russia by name, defense minister General Daoud Yaya Brahim alleged that the “death of our Marshal, weapon in hand” occurred when Chad was “attacked by some powers, we think, by big countries” (Al-Wihda [N’Djamena], September 25, 2021).

Chad’s military rulers are in the midst of a diplomatic campaign to convince its neighbors, military partners and aid sources that their intentions are benign and dedicated to the restoration of democracy in Chad (if Idriss Déby’s regime could be called democratic). To this end, the CMT has made a number of moves intended to generate acceptance of the military junta.

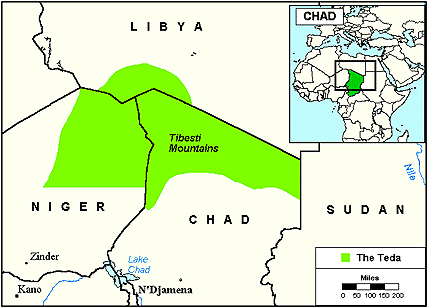

Concerned with the growing Russian influence in both Libya and the CAR, the military council in Chad declared a general amnesty for members of the armed opposition on November 29, 2021. The intent was to promote a resolution to the seemingly endless rebellion so greater strategic threats may be addressed. Responsibility for Qatar-sponsored peace talks was given in late November to Goukouni Waday (or Ouddei), former president of Chad and leader (derde) of the Teda Tubu. Goukouni is well-suited to lead the talks, respected for being part of the royal Tumaghera clan of the Teda Tubu and for having fought in many of Chad’s civil conflicts alongside or against (sometimes both) many of the imprisoned or exiled rebel leaders. Many political prisoners of the Idriss Déby regime were behind bars for “crimes of opinion.” The recommendations of Goukouni’s committee for nearly 300 pardons and amnesties were largely approved, with pardons issued to major rebel leaders, including Mahamat Nouri Allatchi (Anakaza branch of the Daza Tubu), leader of the Union des forces pour la démocratie et le développement (UFDD) rebel coalition, Abakar Tollimi (Bidayat/Zaghawa), president of the Conseil National de la Resistance pour la Democratie (CNRD) and Adouma Hassaballah Djadalrab, former head of the Union des forces pour le changement et la démocratie (UFCD), who has been held in the cells of the secret police in N’Djamena since his extradition from Ethiopia in 2011 (Jeune Afrique, November 24, 2021).

Besides the armed groups, there is also a civil political opposition that rejects the takeover by Mahamat Idriss and the CMT. One of its leaders is economist and politician Succès Masra, who was prevented from running against Idriss Déby in the April 11 election. Masra has pointed out that Mahamat’s succession contravenes the constitution; he and his movement, Les Transformateurs, seek a ban on military officers like Mahamat from running for the presidency, though it may be some time before there is another election. Mahamat Idriss has insisted that “the members of the CMT will not stand for election once their mission has been accomplished” (Africa Report, June 30, 2021). Since the CMT coup, most of the opposition parties have been legalized, including Les Transformateurs.

The Chadian Army

In September 2021 Chad’s defense ministry announced its intention of nearly doubling the size of the Armée Nationale Tchadienne (ANT) to a force of 60,000 troops by the end of 2022. According to General Daoud Yaya Brahim, “the objective is to build elites capable of adapting to the asymmetric warfare our Sahel countries are facing” (Reuters, September 25, 2021).

The army’s reliance on the culturally similar Zaghawa and Tubu minorities of northern Chad for military leadership and recruits for its better-trained and better-paid elite units can create dissension in the ranks and risks to field operations; in 2019, there were two incidents in which northern troops refused to engage relatives in the armed opposition, which is also composed mainly of Zaghawa and Tubu tribesmen. The Chadian minority of African Christian and animist ethnic-groups in southern Chad has played only a minor role in Chad’s military, political or armed opposition leadership since the overthrow of President François Tombalbaye (ethnic Sara) in 1975.

Chad is an important member of both the G5-Sahel, a counter-terrorist and development alliance that also includes Mauritania, Niger, Mali and Burkina Faso, and the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF), a counter-terrorist military alliance battling Islamist extremists in the Lake Chad region. The MNJTF includes Chad, Benin, Nigeria, Cameroon and Niger.

Chad is also a major contributor of troops to peacekeeping missions in the CAR (MINUSCA) and Mali (the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilisation Mission in Mali – MINUSMA).

Ali Darassa Mahamat – Baba Laddé’s Successor

Many African states have limited ability to deliver security to their citizens, especially those where militaries are weak, resources scarce, borders porous, officials corrupt or incompetent and the landscape favorable to banditry or prolonged insurgencies. Rebels have their own challenges, notably in securing steady sources of food, arms, munitions and recruits, so that conflicts tend to drag on for years without conclusion. Eventually both sides adjust to the semi-permanent state of conflict and learn to profit from the instability at the expense of the people both sides pretend to be rescuing. At this point the only apparent chance of restoring peace is to reward rebels and bush warlords with integration into the state security services or administrative structure, often with an understanding they will still be able to carry on their most profitable sidelines.

General Ali Darassa (REUTERS/Emmanuel Braun)

General Ali Darassa (REUTERS/Emmanuel Braun)

Such was the case with the Khartoum peace accord signed in February 2019 (the Accord politique pour la paix et la réconciliation – APPR) by the CAR government and some 14 rebel movements, including the leaders of the main Muslim armed groups in the country. Baba Laddé‘s successor, ‘Ali Darassa Mahamat, leader of the UPC, Mahamat al-Khatim (a.k.a. Mamahat al-Hissène), leader of the Mouvement patriotique pour la Centrafrique (MPC), and Sidiki Abass (a.k.a. Bi Sidi Souleymane), leader of the Retour, Récupération, Réhabilitation (3R) movement, were all made “special military advisors to the office of the prime minister [Firmin Ngrebada at the time]” despite allegations of war crimes and crimes against humanity. As called for in the Khartoum Accord, their men were supposed to be integrated into “special mixed units” with FACA regulars. Each rebel leader was given responsibility in the zone they used to control as insurgents, a frightening prospect for residents who hoped the peace deal would remove the warlords from their regions rather than entrench them with official sanction. The mixed units of rebels and FACA regulars were resisted by Touadéra and never implemented, leaving thousands of gunmen to their own devices while their leaders enjoyed the perks of being a cabinet minister in Bangui.

Darassa’s mainly Mbororo Fulani UPC movement has had repeated clashes with CAR security forces and MINUSCA peacekeepers in the Ouaka prefecture of south-central CAR, especially around the city of Bambari, capital of Ouaka. A raid by Portuguese paratroopers attached to MINUSCA destroyed the UPC headquarters at nearby Bokolobo in January 2019.

Darassa abandoned the Khartoum Accord in August 2020. Shortly afterwards, CAR National Assembly deputy Martin Ziguele accused Darassa of keeping the population of over a dozen towns and villages in slavery, as well as being responsible for the assassination of four Catholic priests (Humanglemedia, August 5, 2020).

The UPC and five other rebel groups formed the Coalition des Patriotes pour le Changement (CPC) on December 15, 2020, with the declared aim of overthrowing President Touadera. However, Ali Darassa announced the UPC’s withdrawal from the CPC in 2021, citing the continuing suffering of the civilian population from political violence. In November 2021, Ali Darassa accused the Wagner Group of committing a series of murders and massacres of CAR civilians, many of them targeting ethnic Fulanis (Corbeaunews-Centrafrique [Bangui], November 30, 2021). However, Ali Darassa’s complaints failed to shift attention from himself and US sanctions were imposed on him on December 16, 2021 in consequence of the UPC’s own “brutal atrocities against civilians” (Reuters, December 17, 2021).

The UPC appears to have been the target of a disinformation campaign when a recent press release bearing the UPC logo announced the dissolution of the UPC. Ali Darassa responded with his own “disclaimer letter” denouncing the “gross lie” perpetrated by President Touadera, the Wagner “killing machine” and livestock minister Hassan Bouba Ali, the “traitor and bastard” of the Fulani community. Darassa promised the UPC was ready to liberate the Central African people from Touadéra and his “blood-drinking allies” (Corbeaunews [Bangui], January 4, 2022). Bouba was earlier condemned by Baba Laddé in September 2021 as “an accomplice in the massacre of his own people” (Corbeaunews, September 24, 2021).

Darassa’s attack on Hassan Bouba was not surprising; Bouba was formerly the number two man in the UPC. A Fulani livestock-trader and former member of Chad’s secret police, Bouba was once close to Baba Laddé. Bouba’s appointment to the government as the UPC’s representative (the Khartoum Accord having called for rebel representation in the government) angered Darassa, who had lost trust in Bouba and opposed his appointment. As Livestock Minister, Bouba acted as the government’s main mediator with the rebels and was its main source of intelligence on rebel activities. Nonetheless, Bouba was arrested in November 2021 in connection to his alleged role in ordering a massacre of 112 civilians at a refugee camp in 2018 (Justiceinfo.net, November 23 2021). Bouba, considered close to the Russian mission, was the only individual actually arrested out of 25 arrest warrants issued for individuals accused of crimes against humanity in the CAR. Instead of facing charges at the Cour pénale spéciale (CPS – Special Criminal Court, a hybrid chamber of local and international magistrates intended to deal with war crimes in the CAR), Bouba was freed by the gendarmes a week later and awarded the National Order of Merit by President Touadéra on November 29, 2021 (Le Monde/AFP, December 8, 2021). The sequence of events confirmed the impunity enjoyed by pro-government warlords and militias.

In recent weeks, UPC operations in Basse-Kotto prefecture (east of Darassa’s stronghold in Ouaka prefecture) have been hampered by a wave of defections and the surrender of “Colonel” Sallé Ali, who claimed Darassa suspected him of being in league with FACA (Radio Nedeke Luka [Bangui], January 7, 2022).

A leading UPC official, Mahamat Abdoulaye Garba, was arrested at the beginning of February. Under interrogation, he confessed to working as an agent of the French Embassy and a conduit for messages from the French to Ali Darassa. Mahamat Abdoulaye was reported to have implicated Baba Laddé in a pro-French conspiracy and to have asked Darassa on behalf of the French what it would take for Darassa to appeal to all Fulani to join a battle against FACA and its Russian allies (Nouvellesplus, February 3, 2022). Seeing a Russian hand in the arrest and interrogation, Darassa responded to the allegations with a press release condemning the Wagner Group’s attempts to “tarnish the image” of France, the Chadian state and its director of intelligence and investigations, General Baba Laddé (Corbeaunews, February 5, 2022).

For Part Two, see: https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4756

Notes

- The Fulani speak a common language (known as Fula, Fulfulde or Pulaar) but are known by several other names in their broad geographical range from the Atlantic to the Red Sea, including Fulbe, Fula, Peul, Peulh, and Fellata. It should be noted that in the 21st century, not all Fulani are cattle herders following traditional means of existence; many are urbanized city dwellers speaking a variety of languages and are well represented in the business communities of the Sahel and the coastal regions of West Africa. For background on the Fulani crisis, see: “The Fulani Crisis: Communal Violence and Radicalization in the Sahel,” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, CTC Sentinel 10(2), February 22, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3881.

- Debriefing statement on its mission to Chad, 16 – 23 April 2018 by the UN Working Group on the use of mercenaries as a means of violating human rights and impeding the right of peoples to self-determination, n.d. (2018), https://www.ohchr.org/en/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=22986&LangID=E

- For Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso, see: “’The Sons of the Land’: Tribal Challenges to the Tuareg Conquest of Northern Mali,” Terrorism Monitor, April 19, 2012, http://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=447; “Mali’s Ganda Iso Militia Splits over Support for Tuareg Rebel Group,” Terrorism Monitor, February 21, 2014, http://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=808.

- Kaka is Chadic Arabic for “Grandmother”; Mahamat was given the nickname after being raised by his grandmother.

- For the Erdimi twins, see https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=2263.