Andrew McGregor

July 30, 2010

When Chad became independent in 1960 the government came under the control of the tribes of the fertile southern region, who formed the majority of the population. However, it was only a few years before the Muslim tribes of the arid north launched a civil war against the regime, culminating in their seizure of power in 1979. Since then control of Chad has been fought over by the small northern tribes of the Borkou/Ennedi/Tibesti region with the majority south as spectators to the often fratricidal conflict. Since 1990, Chad has been ruled by General Idriss Déby, a member of the Bideyat sub-clan of the Zaghawa tribe who took power by mounting an invasion from Darfur with Sudanese backing. Since then, revenues from the discovery of oil in the south have created an even more intense struggle for power among the northern tribes and clans.

For 15 years, twin brothers Tom and Timane Erdimi were the right hand men of the president, handling the most sensitive (and lucrative) portfolios. As nephews of the president they were among his most trusted associates. At the time of their defection to the rebels in 2005, Tom was the President’s permanent undersecretary and chief of oil operations, while Timane was the manager of Cotontchad, the state cotton monopoly (Jeune Afrique-L’Intelligent, December 23, 2005).

For 15 years, twin brothers Tom and Timane Erdimi were the right hand men of the president, handling the most sensitive (and lucrative) portfolios. As nephews of the president they were among his most trusted associates. At the time of their defection to the rebels in 2005, Tom was the President’s permanent undersecretary and chief of oil operations, while Timane was the manager of Cotontchad, the state cotton monopoly (Jeune Afrique-L’Intelligent, December 23, 2005).

Tom Erdimi left Chad and relocated in Houston, where he had connections in the oil industry. It is believed that Tom is responsible for the movement’s financing. Field leadership of the movement was given to Timane, a career civil servant rather than a military man like his opponent Déby.

Déby described his new opponents as “mercenaries,” working for Khartoum’s petrodollars. He said he is “ashamed” for Timane Erdimi:

I know that in the history of wars, there have always been defections to the enemy, traitors to the fatherland and other kinds of persons who make up the fifth column. During the Algerian war of liberation, there were Harkis, Algerians who turned round to fight their own brothers from the ranks of the former colonial power. At the end of the war, they complained that France had abandoned them. Chadian ‘Harkis’ are well advised to meditate on that tragic historical lesson.

The Zaghawa

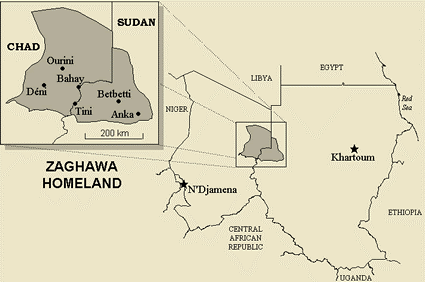

Originating in a homeland that spreads across northern Chad and Darfur, the Zaghawa (who call themselves Beri) are an indigenous African people who have adopted a nomadic, camel herding lifestyle similar to their Arab neighbors. They have their own Nilo-Saharan language, but many speak Arabic and all are now practicing Muslims. In recent decades, however, these poorly known residents of remote regions began a remarkable transformation, achieved partly through their embrace of education. The Zaghawa have demonstrated political, commercial and military skills that have propelled them to an importance far beyond their meager numbers in both Sudan and Chad, where they form only 2% of the population. Their influence has spread as many migrated south to escape drought while others established a successful diaspora community in the Gulf States.

Dar Zaghawa (the land of the Zaghawa) was a victim of late 19th/early 20th century imperialism, being divided between French rule in the west and Anglo-Egyptian rule in the east. The tribe consists of four groups:

- The Zaghawa Kobe, who live mostly in Chad and form the largest Zaghawa group.

- The Zaghawa Wogi, who are split between Chad and the Sudan.

- The Bideyat, who are concentrated in the Ennedi Massif of northeastern Chad.

- The Borogat, who are a mix of Zaghawa and Goran (a Tubu sub-group).

Even within the Zaghawa there are divisions between sub-tribes – the Zaghawa Kobe began to complain in the late 1990s that President Déby was favoring Bideyat over the Kobe in key government positions. Despite this, the Kobe continue to dominate the ranks of the Armée Nationale Tchadienne (ANT), the Garde Républicaine, the police and the intelligence services. They are also the dominant group in Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), the most significant challenge to Khartoum’s rule in the region.

Friction grew within the Zaghawa ruling circle after the Darfur rebellion broke out in 2003. Many were dissatisfied with the level of support Déby was prepared to offer the largely-Zaghawa led insurgent groups, including Dr. Khalil Ibrahim’s JEM and the Sudan Liberation Army-MM of Minni Arcua Minnawi. (a Wogi whose movement has been reduced to members of his own clan after going over to the Khartoum government in 2006).

The Bideyat sub-tribe of the Zaghawa developed a formidable reputation with French and British colonial administrators in the early 20th century. In a 1915 British intelligence report, Harold A. MacMichael described the Bideyat (with colonial prejudices in place) as “an exaggerated form of the Zaghawa. They are darker, wilder, bigger thieves, more independent, more treacherous and live farther North than the latter.” [1] The Bideyat sub-clan, despite its tiny numbers, now controls both the Chadian government and much of the armed opposition.

The Erdimi Brothers Turn Rebel

In June 2005 an Act of Parliament passed allowing Déby to run for a third term as president. The unpopular legislation prompted a trickle of desertions from Déby’s security forces that became a flood in October 2005 as it became apparent Déby was intent on remaining president long after his constitutionally sanctioned two terms were over, possibly even intending to pass on power to his son Brahim. The deserters, including many Zaghawa officers, headed east to join various rebel movements operating near the Sudanese border. Déby was compelled to reorganize his Presidential Guard after a number of defections.

In December, Tom and Timane Erdimi also abandoned the government, sure that regime change was around the corner. The government quickly accused Tom Erdimi of treason, claiming he had embezzled millions of dollars while running state oil operations and had joined in a plot to assassinate the president (IRIN, December 12, 2005). Bideyat anger with Déby had already surfaced in May 2004 with an unsuccessful coup attempt. To further their aims the brothers founded the Rassemblement des Forces Démocratiques (RaFD).

The Erdimis believed they could take a path to power identical to that followed by Déby in 1982 – build a new armed movement in Darfur composed of Zaghawa defectors and then cross 800 km of desert and bush to seize power in N’Djamena. They may well have succeeded in this against a lesser opponent, but despite the corruption and authoritarianism of his government, Idriss Déby has never backed down from a challenge to his rule, even when it appeared his overthrow was imminent; “People tend to forget that I am an old soldier who still keeps an eye open” (Jeune Afrique-L’Intelligent, January 5, 2006).

Rivals and Collaborators in the Rebel Front

In February and early March, 2006 the families of Timan Erdimi and General Seby Aguide Béchibo were both evicted from their state owned buildings and their goods seized on government orders (L’Observateur [N’Djamena], March 1, 2006). Days later, an apparent attempt to shoot down an aircraft carrying President Déby on March 14 was blamed on the Erdimi brothers and General Aguide, a Zaghawa officer who was dismissed from the army on March 10 (AFP, March 15, 2006; IRIN, March 15, 2006).

A daring April 2006 attack on N’djamena by the Front Uni pour le Changement (FUC – drawn mainly from the Tama tribe) forces under Captain Mahamat Nour Abdelkerim. Nour’s decision to risk all on a lighting attack across 800 kilometers was described by Déby as a “suicidal” strategy. Erdimi was also critical of the raid that brought FUC rebels into N’Djamena before being repulsed by government forces; “It is a strategic mistake. One cannot leave the Sudanese border and rush straight to Ndjamena without being backed by one’s rear base” (Jeune Afrique, April 24, 2006). Nevertheless, Mahamat Nour was able to parlay his unsuccessful attack into a short-lived appointment as Defense Minister in Déby’s government.

A rival and sometime collaborator of the Erdimi brothers now emerged in General Mahamat Nouri, a Goran of the Anakaza sub-tribe from Faya-Largeau and an important minister in both the governments of Hissène Habré (also an Anakaza Goran from Faya-Largeau) and Idriss Déby before he quit to join the rebellion in 2005. General Nouri formed the Union des Forces pour la Démocratie et le Developpement (UFDD), composed mainly of Goran tribesmen from the Tibesti region. In reference to Déby and the Bideyat, Nouri said “Chad cannot continue to be governed by one family or tribe,” though Nouri himself is suspected by many other rebels of wanting to restore Goran domination of the government (AFP, February 17, 2008).

A large government offensive in September 2006 attacked the RaFD at Hadjer Marfaine, near the Sudan border. The RaFD claimed to have repelled two columns of troops, capturing 43 soldiers, dozens of transport vehicles and two tanks. Angered by the appearance of French Mirage jets over the battlefield, Timane warned that “all French citizens, military or civil, that fall into the hands of our combatants will be considered as mercenaries and treated accordingly” (AllAfrica.com, September 21, 2006).

Of particular importance to the rebel movement was the eruption of political violence in Dar Tama in September 2006, as Zaghawa gunmen began targeting Tama rebels or suspected rebels. The mainly Zaghawa police force in Dar Tama did little to stop the violence. The army clashed with RaFD rebels again at Guéréda in the heart of Dar Tama in the first week of December, 2006.

Timane Erdimi reorganized the RaFD as the Rassemblement des Forces pour le Changement (RFC). The first fighting between the new RFC and government forces occurred in early December, 2007 during heavy but indecisive fighting in the Kapka hills after the RFC crossed the border from Sudan (IRIN, December 3, 2007; RFI, December 4, 2007).

To the Gates of the Presidential Palace

In January, 2008 the various rebel movements formed a military alliance but could not decide on a common leader. Despite this unfavorable arrangement, the rebels advanced on N’Djamena in three columns, one under Nouri, another under Erdimi and the third under Abd al-Wahid Aboud Makaye, a Salamat Arab. Rejecting the idea of flight to another country, Déby led an outnumbered force into battle at Massaguet, 80 km north of N’Djamena. After some initial success, the fight did not go well for the president, who narrowly evaded capture at one point. Less fortunate was his chief of defense staff, General Daoud Soumain, who was killed in the fighting. As Déby returned to the capital to organize a last-ditch resistance, government troops began to desert in large numbers.

The rebels reached the gates of the Presidential Palace in N’Djamena on February 2, but the offensive then broke against its own core weakness – lack of a single leader. Possibly minutes from taking power, all the ethnic and personal rivalries within the rebel alliance emerged when it could not be decided who would read the victory message over the radio (Sudan Tribune, February 18). The rebels also ran out of ammunition at this point due to what Erdimi’s faction described as the failure of a UFDD convoy bringing ammunition and reinforcements to reach the capital after it was hit by JEM fighters (AFP, February 17, 2008; see also Jeune Afrique February 18, 2008 for an account of the battle). This gave Déby a chance to rally his remaining forces (including a number of JEM fighters) and drive the rebels out of N’Djamena on February 3 with assistance from French forces based in the capital. After the battle French authorities admitted to supplying Déby’s forces with fuel, food, intelligence and Libyan ammunition. French troops also defended the airport and kept it open throughout the fighting, allowing government helicopters to play a decisive role in driving off the attackers (AFP, February 3, 2008; February 7, 2008; February 15, 2008; RFI, February 4, 2008).

After the collapse of the rebel offensive a new rebel coalition formed with Mahamat Nouri as its leader. Defections to a new anti-Nouri movement began immediately, with complaints that Nouri’s leadership had been imposed on the rebels by Khartoum (RFI, March 11, 2008).

The Rebels Try Again

By June, 2008 the rebels were ready to try again, but this time their advance on N’Djamena was halted in a major battle at Am Zoer on June 17 (50 miles north of Abéché). Déby would not allow the National Alliance rebels to close in on N’Djamena and within days of the defeat at Am Zoer the rebels were willing to negotiate, though Déby refused talks until the rebels renounced their ties with Sudan (alwihdainfo.com, June 20; AFP, June 20). Ethnic tensions within the movement and a continued failure to unite behind one leader were cited as reasons for the failure of the rebel advance. The Nouri-Erdimi coalition was doomed to fail as the two had conflicting agendas. Erdimi sought another Zaghawa (preferably himself) to replace Déby as president, while Nouri was firmly against perpetuating Zaghawa control of the country (Alwihda.com, February 21, 2008).

In August 2008, Timane Erdimi received news that he had been sentenced to death in a mass trial held in N’Djamena. Twelve men, including Mahamat Nouri and former president Hissène Habré were sentenced to death in absentia, though Erdimi said; “I’ve heard nothing about this … it is they who should be put on trial” (Reuters, August 15, 2008; AFP, August 15, 2008). Though far from Déby’s reach in Texas, brother Tom was also sentenced to 30 years at hard labor (Le Progres [N’Djamena], July 24, 2008).

Timane Erdimi – The Imposed Leader

In early January, 2009 Erdimi joined his force with several other rebel groups in the Union des Forces de Résistance (UFR) (RFI, January 19, 2009). His leadership of the alliance was reportedly imposed by Khartoum, which also supplied new Chinese-made military equipment (RFI, January 24, 2009). There were challenges to Erdimi’s leadership, however, especially from Mahamat Nouri’s Tama followers who believed it was their turn to rule the country (Tchadactuel, February 3, 2009). In July, Colonel Ahmat Hassaballah Soubiane, a major rebel leader, decided to return home rather than continue under Erdimi’s leadership (Le Temps [N’Djamena], July 27, 2009).

UFR forces fought government troops at the May 7-8, 2009 battle of Am Dam in Chad’s southeastern Salamat region, home to the nomadic Arab Salamat tribe. The UFR forces crossed the border from their bases in Darfur headed for N’Djamena on May 5, but General Toufa Abdoulaye mounted an ambush with the Republican Guard for the rebels roughly 100 km south of Abeché, the old capital of the Sultanate of Wadai, traditional rival of the Sultanate of Darfur. The arrival of armored forces under Chadian Chief-of-Staff General Hassan al-Gadam al-Djineddi prevented the UFR from flanking Abdoulaye’s force and drove them back in disorder to the border with Darfur. Russian-made Sukhoi bombers and MI-8 gunships flown by Ukrainian pilots were also used against the rebel columns (RFI, May 19, 2009). UFR losses were heavy and by December most of its elements had withdrawn its trucks and fighters (RFI, December 10, 2009).

In June, 2009 a website sympathetic to the armed opposition outlined the movement’s grievances with Timane Erdimi’s leadership of the UFR:

- Erdimi had failed to bring about the expected defection of relatives and clansmen still supporting the Déby regime.

- Despite having a large and well-equipped rebel force Erdimi controlled little territory in Chad.

- Erdimi’s political skills were questionable – his only major speech had plagiarized an earlier address by former Haitian president Jean Bertrand Aristide (Alwihda, June 1, 2009).

Consequences of the Chad-Sudan Peace Agreement

A peace agreement between Chad and Sudan reached earlier this year means Khartoum’s active support for the Chadian rebels will end for the time being, though Khartoum would undoubtedly like to keep the armed movements in their back pocket for future use. Erdimi tried to brush off such concerns, stating their fight was “not dependent on relations between Chad and Sudan” (RFI, February 12; AFP, January 22). Nevertheless, the agreement is unpopular with many leading Zaghawa – when JEM leader Dr. Khalil Ibrahim attempted to land in N’Djamena on May 23 on his return to Darfur from Libya via Chad, permission was refused for his plane to land. An incident was avoided when Khalil dissuaded supporters in 300 vehicles from overrunning the airport. The Zaghawa military leadership issued a note to the president criticizing his decision. The president’s brother, Sultan Timan Déby, was reported to be very angry at the refusal to admit Khalil Ibrahim – Sultan Timan is also Khalil’s cousin (Asharq al-Awsat, May 23).

Conclusion

Tom Erdimi’s association with U.S. oil executives in Houston has cost the brothers political support from Libya and France, who continue to support Déby in the interests of regional stability. Erdimi has threatened to mount attacks on the French and American oil infrastructure in the south with the intention of creating enough insecurity to force the United States and France to abandon President Déby. This idea was immediately attacked by Mahamat Nouri; “He should not make threats like that. The petrol sector is for all Chadians. We should be preserving it, not using it for blackmail” (AFP, March 17, 2009; RFI, March 17, 2009). Timane Erdimi views the Déby regime as surviving solely on the support of France, the United States and the World Bank. So far, nothing has come of Erdimi’s threats against the oilfields as the struggle for power remains largely confined to the tribes of the north. With oil providing nearly all the national budget, crippling the industry could also finish Erdimi as a political force in Chad.

Timane Erdimi has always denied acting as a proxy for Khartoum, stating; “We are not auxiliaries of the Sudanese army” (AFP, May 10). However, he is still widely seen as perpetuating the Bideyat-Zaghawa domination of Chadian politics. For all its rhetoric, the Zaghawa armed opposition is fundamentally undemocratic, for no conceivable free election would return the minority Zaghawa to power. Erdimi has admitted that, should he take power, his plan for Chad “is not democracy,” but will rather focus on developing the government’s infrastructure (AFP, April 24).

The Erdimi brothers’ political future does not look bright – Uncle Idriss grips power as tightly as ever in N’Djamena, some of their followers now see them as “yesterday’s men” and they can expect little support from Khartoum, which has signed a deal with Déby to secure Sudan’s western border before next year’s referendum on southern independence.

Notes

- H.A. MacMichael, “Notes on the tribes of Darfur,” Khartoum, 1915 (Sudan National Archives – SNA INTEL 5/3/38).