Andrew McGregor

November 25, 2008

Turkey’s paramilitary Gendarmerie, a frontline unit in the War on Terrorism, is about to undergo some of the greatest changes yet in its long history. The reforms call for a radical restructuring of the organization, designed to generate greater efficiency in counterterrorism efforts as well as assist Turkey in its efforts to join the European Union.

The Gendarmerie (Jandarma Genel Komutanligi – JGK) was founded as part of the 1839 Ottoman Tanzimat reforms. In 1909 it was brought under control of the Ministry of War. The Gendarmes handled interior security during the First World War and played an important part in the War of Independence that followed the Ottoman collapse. Several reorganizations followed before the Gendarmerie became involved in the Cyprus conflict of 1974 (jandarma.tsk.mil.tr). When the struggle began against PKK militants, the Gendarmerie, as the security body responsible for the rural regions of southeast Turkey in which the PKK operated, was naturally involved. Currently, the Gendarmerie has responsibility for security in 92 % of Turkey’s area, containing over one-third of the nation’s population.

The Gendarmerie (Jandarma Genel Komutanligi – JGK) was founded as part of the 1839 Ottoman Tanzimat reforms. In 1909 it was brought under control of the Ministry of War. The Gendarmes handled interior security during the First World War and played an important part in the War of Independence that followed the Ottoman collapse. Several reorganizations followed before the Gendarmerie became involved in the Cyprus conflict of 1974 (jandarma.tsk.mil.tr). When the struggle began against PKK militants, the Gendarmerie, as the security body responsible for the rural regions of southeast Turkey in which the PKK operated, was naturally involved. Currently, the Gendarmerie has responsibility for security in 92 % of Turkey’s area, containing over one-third of the nation’s population.

As a law enforcement agency, the Turkish Gendarmerie falls under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of the Interior, with responsibility for securing public order in areas outside municipal boundaries. The gendarmerie has special responsibilities in the areas of combating smuggling, border control, corrections, enforcing conscription and criminal investigations, as well as being available to perform duties to be determined by the General Staff. In wartime, however, the organization comes under the command of the Turkish General Staff and falls directly under the command of the military. This arrangement is supposed to make the Gendarmerie a more effective entity during times of crises. In practice, however, the Gendarmerie has little interaction with civilian agencies and tends to act as a department of the Turkish military even during times of peace. The reforms intend to eliminate this impractical two-headed command structure, bringing the paramilitary under complete civilian control.

The Gendarmerie is composed of six branches, operating in 13 regional commands spread over Turkey’s 81 provinces:

- Gendarmerie Headquarters and subordinated units

- Internal Security Forces Command (including Gendarmerie commando and aviation units)

- Border Forces Command

- Training Forces Command

- Gendarmerie Schools Command

- Logistics Command

The Gendarmerie is designed to be mobile and is well equipped with armored personnel carriers (APCs), helicopters, and light artillery. The APCs include old but upgraded East German BTR-60PBs, American-designed Cadillac-Gage vehicles, Turkish-built Otokar Akrep and Cobra models, and the Shorland S55, originally designed for service in Northern Ireland. A small force of helicopters includes Sikorsky S-70A28 and S-70A17 Blackhawks, Agusta-Bell AB205A1s, and Russian designed Mi-17 transports. During operations, gendarmerie forces may be transported by helicopter or call in air support from the Turkish Air Force when necessary. The Ozel Jandarma Komando Bolugu (OJKB) is the Gendarmerie’s highly-trained Special Forces unit. It specializes in counterterrorism operations (particularly those against the PKK) and public security activities. Most members of the Gendarmerie are conscript servicemen with only a short training period. NCO’s are selected from those soldiers with at least one year of military service. Officers are recruited while still cadets at the Military Academy and take additional gendarmerie training after finishing their infantry and commando training. They will usually stay with the Gendarmerie for the rest of their career. Gendarmes are typically posted away from their home regions to avoid conflicts of interest. Funerals of gendarmerie conscripts killed fighting the PKK are typically attended by thousands of angry mourners, but their slogans and invective remain directed towards the PKK rather than the government. For the government, this is a useful display of continued public support for a civil conflict that has survived a succession of governments and prevailing ideologies. Reforming the Gendarmerie

Based on decisions taken by the Higher Counterterrorism Board (Terorle Mücadele Yuksek Kurulu – TMYK) and the National Security Council (Milli Guvenlik Kurulu – MGK), the new Gendarmerie will focus on border security and the maintenance of order in rural areas. The force will lose its last areas of responsibility in towns and cities. The command structure will also be reformed, with civilians assuming most of the administrative positions. Both police and gendarmerie will be part of a new Domestic Security Under secretariat of the Interior Ministry (Hurriyet, October 23; Today’s Zaman, November 10). The Gendarmerie commander will no longer be listed among the top four generals of the Turkish armed forces (Turk Silahli Kuvvetleri – TSK) and will become subordinate to the Interior Minister, a reversal of the current protocol (Today’s Zaman, October 25).

While the TSK General Staff appears to have given its consent to the changes (or has at least decided not to oppose them publicly), there has been opposition from within the Gendarmerie command. A letter from General Mustafa Biyik, on behalf of the Gendarmerie command, demanded a reversal of the reforms, accusing the government of ignoring the wishes of the Gendarmerie general command and the organization’s 150 year legacy of service to the state (Taraf, October 26). The Gendarmerie is also proving reluctant to transfer command in urban jurisdictions to the national police.

In August, General Avni Atilla Isik, former staff commander of the Turkish Land Forces, became the new commander of the Gendarmerie. While General Isik has shifted to the Gendarmerie from the army, the new Gendarmerie Chief of Staff is Lieutenant General Mustafa Biyik, a career Gendarmerie officer, having joined the organization in 1975 (jandarma.tsk.tr). Commanders are frequently drawn from the army, returning there after a period with the Gendarmerie.

Addressing a Controversial Legacy

For a force seeking to prove it has adopted European Union standards, the Turkish gendarmerie is facing an embarrassing assortment of court cases related to abuses of power. A court in Trabzon has ruled that the case of two Gendarmerie sergeants accused of having prior knowledge of the 2007 murder of Armenian journalist Hrant Dink can now go to trial. A gendarmerie Colonel is facing similar charges (Today’s Zaman, November 12). Former Gendarmerie commander Sener Eruygur is among those charged with participation in the Ergenekon plot (Yeni Safak, November 9; NTV November 11). Gendarmerie men are among those implicated in the beating death of a detained protestor last month (Anatolia, November 17; Hurriyet, November 17).

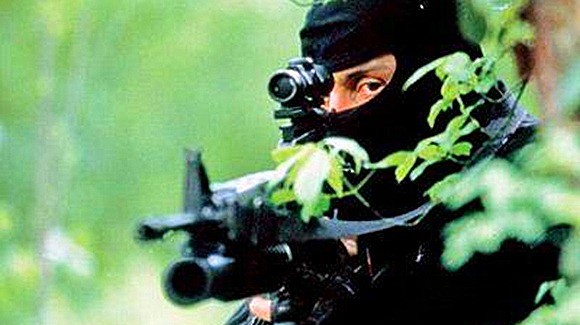

A JITEM Gendarme

A JITEM Gendarme

The most controversial branch of the Gendarmerie does not appear on the command chart. This is the Jandarma Istihbarat ve Terorle Mucadele (JITEM), the Gendarmerie’s intelligence and anti-terrorism department. Long-maintained official denials of JITEM’s existence are now collapsing in the courts, as ex-members of Turkey’s “deep state” security apparatus testify to their participation in covert and illegal activities over the last few decades as part of the ongoing “Ergenekon” investigation. Without any kind of civilian oversight, JITEM appears to have descended into violence and criminality, and are often only tenuously related to the security of the state. A recently-published book by a former JITEM officer, Abdulkadir Aygan, describes a force for which assassinations were normal business and even attacks on the state itself were considered permissible. [1]

As part of the Ergenekon investigation, retired general Veli Kucuk admitted to being the leader of JITEM after taking over from founder Arif Dogan in 1990 (Zaman, January 30). JITEM appears to have been composed largely of ex-PKK members and NCOs of the Gendarmerie, operating in small, largely autonomous cells specializing in false-flag operations. According to Aygan, torture was common and detainees were often killed.

A May 2008 study produced by Istanbul’s Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation addressed the problem of the lack of oversight of gendarmerie activities related to national security. According to author Ibrahim Cerrah, a professor at the Turkish Police Academy, institutional reforms are needed to raise the ethical standards of Turkey’s gendarmes and police, which have often resorted to extra-judicial means in countering threats to internal stability:

Legal and ethical violations by some security personnel may occur in the name of perceived higher ideals, such as the protection of the higher interests of the state and the nation, without consideration for any personal interest. However, it has been observed in the past that legal and ethical violations for short-term benefits can in the long run cause more harm than good to the principles defended and to the country… It is a fact that the problem of illegal and unethical acts committed by some security sector personnel is not sufficiently addressed. The most important reason for this is professional solidarity resulting from professional socialization… Members of the security profession are in a kind of unwritten agreement to protect each other and not to speak out against each other, outside of exceptional and compulsory situations. [2]

Independent inspection of the Gendarmerie as required by EU regulations has so far foundered because of the organization’s dual allegiance – its connection to the General Staff makes any outside inspection impossible without the approval or even participation of the General Staff itself (Turkish Daily News, May 14). The EU’s November progress report on Turkey stated; “no progress has been made on enhancing civilian control over the Gendarmerie’s law enforcement activities”. [3]

The JGK Commandos

Other reforms directed at Turkey’s commando forces will have an impact on the Gendarmerie, which maintains one brigade of commandos to the army’s five. The reforms are designed to professionalize the commandos, with only officers and volunteer NCOs of the rank of sergeant and above being allowed to join the force (Hurriyet, May 8). The move to professional troops will solve the problem of conscripts leaving the armed forces once their term of enlistment is up, giving the commandos the benefit of experience and continuity in their efforts. The new commandos will receive hazard pay for serving in southeast Turkey, the focus of fighting with the PKK.

Conclusion

Professionalization of the gendarmerie is being imposed by necessity. As law enforcement techniques become more sophisticated, a lack of education common to many conscripts is beginning to hamper operations, especially those done in conjunction with the generally better-educated police services. Changes in personnel recruitment are being matched by improvements in equipment, with ongoing modernization programs aimed at command and communications systems, weaponry, vehicles and other equipment. With unification under Interior Ministry command, the police and the gendarmerie are being encouraged to carry out greater intelligence cooperation, an ongoing problem in the Turkish security services.

An important indication of the Gendarmerie’s new field of responsibility may be found in Ankara’s recent approval of the construction of 118 new posts along the border with Iraq, along with the construction of roads linking the posts to urban centers and other necessary infrastructure (Today’s Zaman, November 14). The Gendarmerie is about to become a frontier force, with long postings in sparsely populated and largely inaccessible regions. In this sense, the Gendarmerie’s resistance to losing its last urban areas of responsibility is understandable. The important reforms to Turkey’s internal security structure may be seen as part of a general trend in Europe away from paramilitary Gendarmerie-type security services.

Notes

- See also Ferhat Unlu’s extensive interview with Abdulkadir Aygan, Sabah, August 25.

2. Ibrahim Cerrah, Police Ethics and The Vocational Socialization of the Security Personnel in Turkey, Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation (TESEV), Istanbul, May 2008, p.40.

3. Turkey 2008 Progress Report, Commission of the European Communities, November 5.

This article first appeared in the November 25, 2008 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor

Major General (Ret.) Amir Faisal Alvi

Major General (Ret.) Amir Faisal Alvi