Andrew McGregor

Terrorism Monitor, November 2, 2012

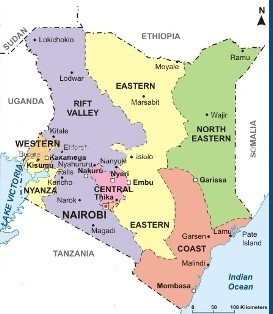

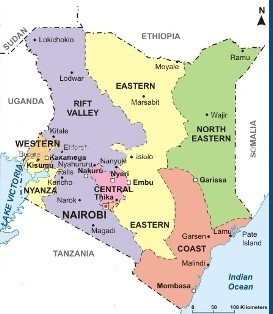

Kenya’s decision to launch a military intervention in Somalia to eliminate the threat posed by the Islamist al-Shabaab movement has resulted in battlefield successes but has also led to terrorist attacks and riots in the cities of Nairobi and Mombasa and even the formation of a Kenyan chapter of al-Shabaab. Simultaneous with these events are a growing number of incidents of political violence in Kenya’s largely Islamic Coast Province, a region with an active secessionist movement that operates under the name of the Mombasa Republican Council (MRC).

Formed in 1999, the MRC has until recently focused on legal means of attaining independence for the Coast region, which has significant cultural, linguistic, ethnic, historical and religious differences from the inland regions of Kenya where national power is held. In the Coast Province, the dominant culture and language is Swahili, which reflects a Bantu core and strong influences from Arab, Asian and European sources. Most indigenous residents refer to themselves as “Coasterians” rather than “Kenyans” and have numerous grievances with the Nairobi government over issues such as underdevelopment, poverty, land ownership, unemployment and government projects that bring few benefits to Coast residents.

Formed in 1999, the MRC has until recently focused on legal means of attaining independence for the Coast region, which has significant cultural, linguistic, ethnic, historical and religious differences from the inland regions of Kenya where national power is held. In the Coast Province, the dominant culture and language is Swahili, which reflects a Bantu core and strong influences from Arab, Asian and European sources. Most indigenous residents refer to themselves as “Coasterians” rather than “Kenyans” and have numerous grievances with the Nairobi government over issues such as underdevelopment, poverty, land ownership, unemployment and government projects that bring few benefits to Coast residents.

Background:

A Question of Sovereignty

The Coast Province consists of the coastal strip of Kenya on the Indian Ocean and is inhabited by Mijikenda, Swahili and Arab peoples, representing a population of roughly 22.5 million. The coastal region came under the rule of Omani Arabs based in Zanzibar after they expelled Portuguese colonists in the late 18th century following 200 years of rule. The Sultan of Zanzibar agreed to lease the coastal region of modern Kenya (then known as “al-Zanj”) to the Imperial British East Africa Company in 1888. An 1895 treaty between Britain and the Sultan brought the region under formal British protection, with the residents remaining subjects of the Sultan rather than subjects of the British crown, as in the Kenya colony. It is this point that is the principal basis for the MRC’s legal challenges to its incorporation into post-independence Kenya. [1]

Some MRC members also claim that Jomo Kenyatta, the first prime minister of Kenya, had signed a separate 50-year lease agreement for the Coast strip with Zanzibar that will expire next year, when the Coast region will become independent. However, the movement cannot produce documentation of this claim and there is no reference to it in the existing agreements on which the Kenyan state was founded (Institute for Security Studies [Nairobi], June 27).

A 1908 British ordinance usurped most of the traditional claims to land-ownership on the Coast by declaring all land not under cultivation to be “crown land,” thus transferring title to most of the Coast to the state, a system inherited by modern Kenya, which has used the distribution of such lands to up-country Kenyans as a means of patronage or as the basis of resettlement schemes and industrial projects that do little for Coast residents. Little of the wealth created in the region by its busy ports and flourishing tourist industry makes its way into the hands of locals, who face wide-scale unemployment and land loss through various land reforms favoring landholders from the interior. In this economically depressed environment many young men are turning to heroin use while impoverished young women are often absorbed into Mombasa’s sex trade.

In the lead-up to Kenya’s independence in 1963, Coast residents tended to join either the mwambao (Swahili, lit. “coastline”; in this context meaning “self-governing”) or majimbo (Swahili, lit. “regions,” i.e. federalist) camps. The mwambao movement began in the years prior to independence as Coastal Arabs and Swahili feared being taken over by local Africans and migrants from the “upcountry” regions of Kenya. Unfortunately, many Coast residents believed Kenyan independence would mean the restoration of their lands, not their transfer to a new authority. [2] The majimbo current ultimately prevailed, but many of its proponents on the Coast later changed their mind when various protections and guarantees granted to the Coast were pushed aside by the post-independence government. The new nation of Kenya was, in part, an assembly of unwilling elements under the dominance of the tribes of the highland region, with many in the coastal region and the north-eastern ethnic Somali region having serious reservations about union with Kenya.

The Kaya Bomba Raiders

Prior to Kenya’s 1997 general elections, shadowy figures thought to be agents of the governing Kenya African National Union (KANU) began organizing Coast youth and veterans bitter over alleged discrimination in the Kenyan military and government land distribution policies at a base at Kaya Bombo in Kwale District. Most of the recruits hailed from the Digo, one of the nine tribes composing the Mijikenda group (a largely colonial construct). Dressed in black robes bearing a star and crescent moon and armed with firearms and machetes, the Raiders slaughtered up-country people as well as many non-Digo coastal residents who could not respond to Digo greetings, this being the main method of determining who was native to the region and who came from up-country.

The performance of the General Service Unit (GSU) paramilitary and other Kenyan police units in combating the Kaya Bomba Raiders was so inept that even some of the militants came to the conclusion that the repeated refusals of the security forces to engage or pursue the raiders even under favorable conditions and the transfer out of the region of veteran police officers familiar with the terrain meant the militants were serving a political purpose, likely by disrupting coast society during voter registration. GSU methods focused on rounding up unarmed members of the Digo and subjecting them to arbitrary arrest, beatings, torture and rape. [3] The MRC has repeatedly denounced the Kaya Bomba Raiders, characterizing their “revolt” as an episode of state-organized political violence at odds with the objectives and methods of the MRC.

Kenyan Police Display Seized MRC Materials

Kenyan Police Display Seized MRC Materials

The Rise of the Mombasa Republican Council

Since its formation, the MRC has pursued its quest for independence in the courts, citing the questionable status of the Coast region at the time of independence. The movement employs two main slogans; Pwani Si Kenya (“The Coast is not part of Kenya”) and Nchi Mpya Maisha Mpya (“New country, new life”), and is jointly governed by a Leadership Council composed of the movement’s executives and the more secretive Council of Elders. All MRC recruits go through an initiation known as “oathing.” This ceremony is an important exercise in the creation of secret societies on the Kenyan Coast. From various descriptions, the oathing usually consists of a ritual applied to recruits in a spiritually important place (such as a forest) involving ritual bloodletting and the taking of an oath to maintain secrecy and follow orders explicitly. In return, the new member receives supernatural protection from enemy weapons and the ability to render himself invisible from his enemies. [4]

Belief in supernatural forces has always been strong in the Coast region, but there are a growing number of young, educated “Coasterians” who reject what they describe as the deceptions practiced by local sorcerers and practitioners of witchcraft. Oathing itself is clearly based on pre-Islamic beliefs and folk traditions beyond the pale for most members of Salafist groups such as al-Shabaab or their allied organizations in Nairobi and Mombasa.

When the Kenyan government banned the MRC in October, 2010, the movement did not take up arms but instead took the government to court, achieving a surprising repeal of the ban from the Mombasa High Court on July 25 of this year. This success, however, only raised suspicions in some Kenyan quarters of the movement’s source of financing in light of the generally impoverished condition of its leadership (Nairobi Star, October 20). On October 9, security officials announced they had opened an investigation of several MPs and a number of businessmen related to support and funding of the MRC (The Standard [Nairobi], October 10; Capital FM, October 13). A prominent Muslim leader and member of parliament, Shaykh Muhammad Dor, was arrested on October 17 on charges of inciting violence after endorsing the MRC and promising to fund it “if asked” because it was “not an outlawed group” (Capital FM [Nairobi], October 19; AFP, October 18).

Violence Begins to Spread in the Coast Region

Grenade attacks in the Coast Province began in late March with an attack on a restaurant in Mombasa and another in the town of Mtwapa (AFP, March 31). An oathing ceremony at Kaloleni in the Kilifi District turned deadly on September 27 when a village elder was killed by people alleged to be involved in an oathing in the nearby forest. Local residents had watched the strangers arriving in the area and feared they were preparing an attack on Kaloleni. Villagers pursued the roughly 200 men and killed eleven of them, including seven by stoning. Four more men alleged to have been MRC members escaping the initial massacre were lynched after they tried to hijack a car in Samburu (Daily Nation [Nairobi], September 29). Eight men, including an alleged “witchdoctor” responsible for administering the oaths were arrested and charged with various offenses (Standard [Nairobi], September 28; October 2).

After the lynchings, local police displayed items used in the oathing ceremonies, including flags, sheep heads, fresh sheep skins, black and red cloth, machetes, knives and various “concoctions” (Daily Nation [Nairobi], September 29). However, one security source told journalists that “This was not the MRC. It is an entirely new group and it looks like we have a bigger security problem” (PANA Online, September 29).MP Najib Balala, the leader of the Republican Congress Party of Kenya, said that the MRC has legitimate grievances and was only fighting for justice: “We know what the MRC is. We have not seen terrorism in its face” (Nairobi Star, October 2).

Kenyan authorities blamed the MRC for a vicious machete attack on Fisheries Minister Amason Kingi at a campaign rally just north of Mombasa on October 4. Kingi survived the attack due to the efforts of his bodyguard, who was hacked to death before those attending the rally beat the three attackers to death (PANA Online, October 22). The Minister is considered the point man in the Coast region for Prime Minister Raila Odinga of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), who is running for president in the coming elections (PANA Online, October 5). Odinga commented on the violence in the Coast region: “It looks to me like there are people who want to disrupt the elections and the registration of voters especially in the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) zones so that people cannot register and eventually vote” (PANA Online, October 9). According to Coast Provincial Police commander Aggrey Adoli, the attackers were MRC members who had just arrived from a forest where they had taken the oath. Adoli went on to advise local politicians to examine the MRC’s beliefs closely before offering their support to the movement (The People [Nairobi], October 8). However, MRC spokesman Rashid Mraja said that these and other youth found taking the oath in Coat region forests by security forces had been paid by local businessmen and politicians to join a violent militia (“the Muyeye movement”) designed to discredit the MRC’s calls for secession and ultimately lead to fighting between the two groups (The People [Nairobi], October 8).

GSU detachments are currently engaged in a disarmament campaign in the Tana River district and the pursuit of some 2,000 youth alleged to have taken the MRC oath in September (Daily Nation [Nairobi], October 22). A group of Tana residents have threatened to sue the GSU for alleged atrocities carried out during the campaign (KBC-TV, September 26). The district is host to long-standing tensions between Pokomo agriculturalists and Orma pastoraslists over access to water. These tensions exploded on August 22, when the Pokomo attacked an Orma camp, killing 62 men, women and children with machetes, spears and handguns (al-Jazeera, August 22). Further violence followed in a pair of retaliatory attacks on other villages in the district, killing another 50 people, including nine police officers (K24TV, September 7; Daily Nation [Nairobi], October 1). Despite the dispute over water rights, it appears to have been political considerations that set off the violence, with the Pokomo hoping to disrupt voter registration amongst the Orma in Tana River District, where all three MPs currently hail from the Pokomo tribe. A local MP, Dhadho Godhana, was dropped from cabinet and charged with inciting violence in the Tana River delta amidst claims from villagers that their attackers included many people they did not recognize and who appeared to be organizing the massacres (AFP, September 14). Muslim clerics in the region have told the tribes they are being used for political purposes and have urged them to form a peace council to prevent further violence (Nairobi Star, October 2).

Kenyan police reported that a group of suspected MRC members raided their camp in Likoni with “crude weapons” in the early hours of October 20. Three days earlier, a GSU officer was killed in a grenade attack (Daily Nation [Nairobi], October 17, October 20).

Sweeping Up the MRC Leadership

The MRC’s existence as a legal entity was short-lived, as the Mombasa Chief Magistrate accepted an application by the state and once again outlawed the MRC, ordering police to arrest all its leaders and present them in court to face fresh indictments (PANA Online, October 22). By coming back under an official ban, MRC activists will now be subject to the sweeping new powers given to security forces by the Prevention of Terrorism bill currently on its way to a third and final reading in the Kenyan parliament (KBC-TV, September 27; Standard [Nairobi], Spetember 27).

On October 14, police raided the home of MRC leader Omar Hamisi Mwamnuadzi in Kombani, south of Mombasa. Mwamnuadzi had gone into hiding after security forces began a crackdown on various groups on October 8. Police reported that they were met at the road leading to the MRC leader’s home by two bodyguards who threw a petrol bomb at a police vehicle. The bomb failed to explode and the two men were killed by police who then arrested 38 people, including Mwamnuadzi and his wife. The entire arsenal seized consisted of only four petrol bombs, one AK-47 rifle and 15 rounds of ammunition (Daily Nation [Nairobi], October 15).

After his arrest, Mwamnadzi was charged with possession of the firearm and 15 rounds of ammunition. Both the MRC leader and his wife, Maimuna Hamisis Mwavyombo, were additionally charged with practicing witchcraft and possessing articles used in witchcraft (Daily Nation [Nairobi], October 22). Police pointed to the MRC after a local administration official accused of giving out Mwamnuadzi’s location was the victim of a violent murder shortly after the MRC leader’s arrest (PANA Online, October 16).

At his release, Mwamnuadzi appeared to have been the victim of a severe beating, which he claimed was administered during his arrest, his death having been prevented only through the intercession of his bodyguards. The MRC leader lost four teeth while being detained and was unable to raise the $36,000 bond for his release and that of his wife (Nairobi Star, October 20).

Kenyan president Mwai Kibaki used a national “Heroes Day” broadcast on October 20 to warn the MRC that the government “will take firm and decisive action in dealing with those who have issued threats of secession or those who threaten our security. Kenya is one unitary state. The constitution is clear and so is our history. Let us learn from that history and not seek to distort it…” (KBC TV, October 20).

Other MRC leaders have been systematically rounded up or surrendered to security forces in recent days:

• Spokesman Muhammad Rashid Mraja was arrested on October 8 for calling for the secession of the Coast region and failed to make bail (KBC Online, October 8).

• Secretary General Randu Nzwai Ruwa was charged with incitement to violence on October 10 and released on $24,000 bail. (KBC, October 10).

• Treasurer Omar Suleiman Babu (a.k.a. Bam Bam) surrendered to police on October 23.

• Council of Elders’ chairman Hassan Mbwana Mwanguza was arrested in early October.

Islamist Connections?

In late September, Somalia’s al-Shabaab Islamists announced the creation of a Kenyan branch of the movement to be led by Shaykh Ahmed Iman Ali, the founder of the Shabaab-allied Muslim Youth Center (MYC, a.k.a. Pumwani Muslim Youth – PMY). Shaykh Ahmed quickly indicated the group would pursue revenge for al-Shabaab’s loss of the port of Kismayo to the Kenyan military by calling for “all means possible” to be used to kill the “infidels” in Mombasa, Nairobi “and across East Africa.” [5] In this environment, it is likely that Kenyan authorities will conflate political resistance (violent or non-violent) by the Coast Muslims of the MRC with the more serious pro-Shabaab Salafist threat. During an October 11 cabinet meeting, Kenyan ministers downplayed the possibility the recent violence on the Coast was motivated by local dissatisfaction with the government, suggesting instead that it was the work of al-Shabaab infiltrators and absentee landlords who had been adversely affected by changes to the land laws (Daily Nation [Nairobi], October 12).

Despite the attempt to paint the MRC as a religious-based movement, some Mombasa businessmen have more concrete reasons for disliking Kenya’s intervention in Somalia, as many made sizable profits by dealing contraband across the mutual border (Business Daily [Nairobi], October 8). It should also be noted that the MRC is not an exclusively Muslim organization. Pentecostal churches and pastors are reported to play a large part in MRC organizing activities. A pastor was among those MRC suspects arrested in a recent GRU operation in Tana River District (Daily Nation [Nairobi], October 22).

Conclusion

There is suspicion that Nairobi’s sudden offensive against MRC leaders is designed to disrupt election preparations in the Coast region, where Raila Odinga’s ODM took most of the vote in the 2007 elections, in which 1,200 people were killed and 600,000 displaced in post-election violence across Kenya after Odinga accused President Mwai Kibaki of rigging the vote. Outlawing the MRC brings the risk of greater political violence as the membership is forced to go underground. In current conditions, it appears unlikely that the MRC will be allowed to continue their recourse to the courts to address the group’s core issues.

Nevertheless, the MRC’s actual commitment to secession appears rather weak; the coast, after all, was never an independent state, coming at various times in various places under the rule or protection of the Portuguese, the Omani Arabs, the Germans, the British and finally the rule of Nairobi. Coastal independence is a goal not shared by the Salafists, who are pursuing an East African Islamic Caliphate that would include Somalia, the coasts of Kenya and Tanzania and other predominantly Muslim parts of the region.

The loose organization of the MRC and its informal membership system creates several problems for the movement, including the risk of infiltration by security forces, political manipulators or militants who do not share the MRC’s the movement’s goals and non-violent strategies. The MRC Youth Wing especially is agitating for stronger responses to state repression of the movement, but the repeated lynchings of those believed to be planning violence in the region reveals a popular distaste for any repetition of Kaya Bomba-type attacks and the often indiscriminate repression that followed. Despite this, movement leaders admit they are having difficulty in keeping the youth wing in check

MRC statements do not display any mention of or support for jihadi/Islamist agendas and the religion practiced by most Muslim MRC members incorporates traditional Islamic and folk beliefs rather than the austere Salafism that characterizes most of the Islamist movement. However, continuing speculation from government administrators that the MRC is allied with al-Shabaab and the challenge posed by the MRC’s call for a boycott of the forthcoming March 2013 general elections is likely to keep the MRC on the list of banned organizations. With the incarceration of most of the movement’s leadership, the MRC youth wing will remain susceptible to both political manipulation and even enticements from foreign jihadists able to promise a more forceful response to the government crackdown in the Coast region.

Notes

1. James R. Brennan, “Lowering the Sultan’s Flag: Sovereignty and Decolonization in Coastal Kenya,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 50(4), 2008, pp. 831-861.

2. See Paul Goldsmith, “The Mombasa Republican Council Conflict Assessment: Threats and Opportunities for Engagement,” Kenya Community Support Center, November 2011, http://www.kecosce.org/downloads/MRC_Conflict_Assessment_Threats_and_Opportunities_for_Engagement.pdf , and “Playing with Fire: Weapons Proliferation, Political Violence and Human Rights in Kenya,” Human Rights Watch, New York, 2002.

3. Ibid, p.13.

4. “Playing with Fire: Weapons Proliferation, Political Violence and Human Rights in Kenya,” Human Rights Watch, New York, 2002, pp. 30-32.

5. Al-Kataib, October 19, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tdY8IDaBGTU

Fire that followed a bomb explosion during the raid on a Madinat Nasr building.

Fire that followed a bomb explosion during the raid on a Madinat Nasr building.