Andrew McGregor

June 1, 2019

A little-known five-year civil war in South Sudan has left up to 400,000 dead and millions more displaced. After the young nation gained its hard-won independence in 2011, only two years of peace followed before latent rivalries between the Dinka and the Nuer (the two largest and most powerful of South Sudan’s 62 recognized ethnic-groups) resurfaced. In December 2013, President Salva Kiir Mayardit (Dinka) accused his vice president, Dr. Riek Machar Teny (Nuer), of planning a coup against the ruling Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM). Machar denied it, but was soon leading a largely Nuer army opposed to the government—the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement in Opposition (SPLM-IO). In time, other ethnic groups were pulled into the struggle. [1] Many of these smaller groups (especially in Equatoria) had joined pro-Khartoum militias during the 1983-2005 Second Sudanese Civil War, creating a lasting friction with the Dinka who provided the bulk of the rebel SPLA manpower.

The first two years of the war largely avoided Equatoria, the traditional name for the southern third of the nation where there are relatively few Dinka and Nuer. A year-long peace agreement signed in 2015 could not survive growing perceptions that President Kiir’s regime was promoting Dinka superiority at the expense of other ethnic groups. New tribal-based armed movements emerged and the war erupted once more. This time, SPLM-IO forces shifted into the forests of Equatoria, with the government’s Dinka-dominated Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) following them in pursuit. Equatoria’s many ethnic groups were soon forming their own armed self-defense forces gathered into highly fluid alliances.

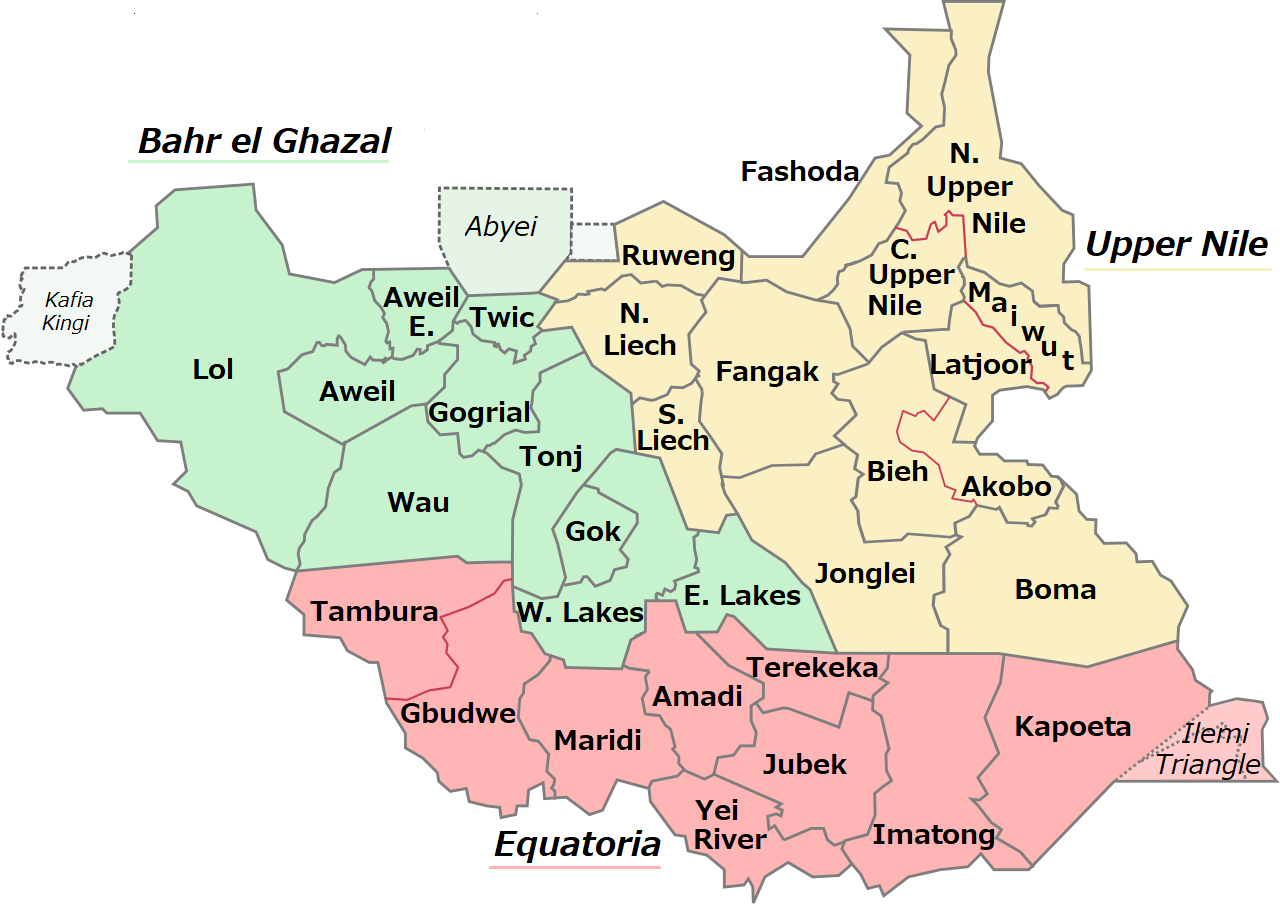

Fueling the conflict in Equatoria and elsewhere was the regime’s unpopular division of South Sudan’s original ten states into 28 (and later 32). Again, this was perceived as an effort to establish Dinka majorities in various regions, all governed by Dinkas appointed by and loyal to the president. Many Equatorians prefer a return to a single region rather than the current arrangement of nine small Equatorian states imposed in 2017. Southern Sudan is traditionally understood as three distinct regions – Upper Nile, Bahr al-Ghazal, and Equatoria.

With 3.5 billion barrels of proven reserves of crude oil, South Sudan should be enjoying rapid development and significant improvements in living standards. Instead, the ongoing fighting has halved oil production and most oil revenues are spent on military equipment.

A General from Equatoria

The government, the SPLM-IO, and a number of smaller armed groups signed a new peace deal in August 2018, the Revitalized Agreement on Resolution of Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan (R-ARCSS). Leading the armed opposition to the agreement and  Thomas Cirilo in SPLA Uniform

Thomas Cirilo in SPLA Uniform

the Kiir regime is Lieutenant General Thomas Cirilo Swaka, a member of the Bari tribe (a cross-border group also found in northern Uganda) and a former leading general in the SPLA.

Hailing from the South Sudanese capital of Juba, Cirilo fought against the Khartoum regime during the Second Sudanese Civil War, surviving a landmine blast that left an eight-inch scar on his head. By the time South Sudan gained its independence in 2011, Cirilo was already head of the SPLA’s training and research division. In February 2016, he became the SPLA’s deputy chief of general staff for logistics. Having maintained a fairly low profile, he took some by surprise when he resigned from the SPLA in February 2017, becoming the second highest ranking officer to defect from the SPLA. Cirilo established a new rebel movement, the National Salvation Front (NSF), the following month. The movement is better known as “NAS,” meaning “people” in Juba Arabic. At the time of his resignation, Cirilo claimed President Kiir had turned South Sudan’s military, police and security services into a Dinka-dominated “tribal army” (African News/Reuters, March 7, 2017).

Cirilo claims he was sidelined during the Kiir regime’s worst abuses and largely powerless to stop them (Reuters, May 5, 2017). A presidential spokesman, on the other hand, noted that Cirilo had a major command position in the SPLA in those years, was part of the decision-making process and therefore “bears the consequences of what the SPLA as an army has actually done” (February 14, 2017).

Reasons for Rebellion

When he resigned, Cirilo issued a statement claiming “President Kiir and his Dinka leadership clique have tactically and systematically transformed the SPLA into a partisan and tribal army…Terrorizing their opponents, real or perceived, has become a preoccupation of the government.” Cirilo went on to state that extensive recruiting in the security forces was ongoing among the Dinka of President Kiir’s home region and that these forces were being deployed to occupy land belonging to other tribal and ethnic groups using methods involving rape, murder, and torture (February 11, 2017). Allegations of regime corruption, economic mismanagement and an inability to maintain law and order were also made (Pachodo.org, December 2017).

In the overcharged political atmosphere of the national capital it was not surprising that the U.S. embassy in that city was compelled to refute charges in the local press that the CIA was backing Cirilo in order to overthrow the Salva Kiir government (Sudan Tribune, March 16, 2017). These charges were revived in September 2018 by South Sudanese intelligence while Cirilo was touring the United States to raise support for his movement: “We are not sure of why he is gone to the U.S., but we know he is there, being sponsored by the CIA” (East African [Nairobi], September 4, 2018).

War in Equatoria

President Kiir offered Cirilo an amnesty in September 2017 that would have allowed the general to rejoin the SPLA or form his own political party, but the offer was refused (Sudan Tribune, September 5, 2017).

SPLA-IO patrol in Kajo Keji (The Nation, Nairobi).

SPLA-IO patrol in Kajo Keji (The Nation, Nairobi).

Cirilo’s troops instead clashed with Machar’s SPLA-IO in mid-October 2017 in the Kajo Keji region close to the Ugandan border. The region, a part of Yei River State where NAS is especially strong, is a strategic transit point for rebel movements and its control allows for the importation of supplies from Uganda (October 19, 2017).

Many clashes occur in remote locations, leaving only the spokesmen for both sides as sources. Typical of the credibility issues this presents was a 2017 clash between SPLM/A-IO and the forces of Lieutenant General John Kenyi Luboron. Luboron had defected to NAS from the SPLM/A-IO only days earlier, citing internal feuds in the SPLM/A-IO leadership, neglect of the forces under General Kenyi and the “unnecessary and random promotion of officers” (Minbane, July 29, 2017; Sudan Tribune, July 30, 2017).

The SPLM/A-IO claimed to have quickly overrun Kenyi’s base at Nyori, forcing the defector and his men to flee into the bush. According to NAS, Kenyi repulsed two SPLM/A-IO attacks on his base before pursuing the attackers (NAS Press Release, August 4, 2017, Reuters, July 30, 2017).

Colonel Nyariji Jermilili Roman repeated charges of military negligence in the course of his own resignation from the SPLM/A-IO, accusing Machar of deliberately neglecting the SPLM/A-IO forces in Equatoria:

You intentionally failed to supply our forces in Equatoria with arms and necessary logistical support, an act that endangered many of our men’s lives because their capacity to defend themselves was greatly affected, hence the death of General Elias Lino Jada and General Martin Kenyi (Sudan Tribune, March 13, 2017).

General Martin Terensio Kenyi was killed in a battle in Lobonok (Jubek State) in June 2016. General Elias Lindo was allegedly assassinated together with prominent lawyer Peter Abd al-Rahman Sule by South Sudan security agents in Uganda in 2015. Their remains were never recovered: they were believed to have been thrown into the crocodile-infested waters of the White Nile, a common method of disposing of political prisoners during the rule of Idi Amin Dada (South Sudan Liberty News, August 22, 2015).

Initially, Cirilo’s leadership attracted other armed groups in Equatoria. Among these was the South Sudan Democratic Movement (SSDM, aka “Cobra Faction”), led by General Khalid Butrus Bora (Murle). The movement’s former leader, David Yau Yau (Murle), signed a peace agreement in 2015 and joined the government, leaving the Cobra faction in the field. General Butrus, who resigned from the SPLA in 2016, warned that Dinka civilians had been issued heavy weapons and encouraged to attack Murle communities in eastern Equatoria (VOA, March 9, 2017). To counter this, Butrus merged the SSDM with NAS on March 9, 2017 (SouthSudanNation.com, March 9, 2017).

Cirilo’s movement suffers from a near-constant shortage of ammunition, a fact well-known to their enemies. Many NAS fighters are armed solely with bows and arrows. Nonetheless, Cirilo remains defiant: “We’re not going to stop. If Juba thinks that without bullets we’re not going to be able to protect ourselves and our people they’re wrong” (Vice.com, February 15).

NAS has also been vulnerable to defections. On June 15, 2018, Lieutenant Colonel John Kaden Elisa led 137 fighters away from NAS in order to rejoin the SPLM/A-IO. Kaden insisted the men had been ordered by Lieutenant General John Kenny Latio to defect to NAS and fight the SPLM/A-IO, actions that they now regretted. Cirilo’s failure or inability to provide arms and his insistence they fight the SPLM/A-IO rather than regime forces were cited as major reasons for their return to the SPLM/A-IO (Daily Monitor [Kampala], June 16, 2018).

Further defections would follow. In mid-November 2018, the SPLM/A-IO reported that Brigadier Peter Yugu Laku and Colonel Augustino Modi had returned to the SPLM/A-IO with “90% of their fighters” after having defected to NAS in August 2017. A NAS spokesman claimed the SPLM/A-IO had then mounted a joint operation with the South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF, the re-named SPLA as of October 2, 2018) against NAS forces in Lobonok, though a SPLM/A-IO spokesman denied the operation existed and suggested that NAS “look after their own mess” (Sudan Tribune, November 20, 2018).

The Brown Caterpillars

South Sudan Foreign Minister Nhial Deng Nhial provided a positive report on human rights in his country to the UN’s Human Rights Council (UNHCR) in April despite a massive cross-border refugee outflow from Equatoria, the biggest crisis of its type in Africa since 1994. In response, Cirilo sent a three-page letter to the council refuting the minister’s claims:

The realities on the ground show that there’s no peace in the country and fighting is going on as we speak… the current tragedy in the Yei River area where tens of thousands of civilians fled their homes seeking safety in the neighboring countries refutes the government’s false claims… NAS forces have come under relentless attacks by the SSPDF and the [Mathiang Anyoor] militia affiliated to it (Sudan Tribune, March 3).

General Paul Malong Awan (Radio Tamazuj)

General Paul Malong Awan (Radio Tamazuj)

Mathiang Anyoor (“Brown Caterpillar”) is an ethnic-Dinka militia formed by former SPLA chief of general staff Paul Malong Awan (Dinka) as a personal guard for himself and President Kiir. The group, recruited largely from the Northern Bahr al-Ghazal and the Warrap region, is well-armed, though its direct connection to the army is uncertain. The militia split in May 2017 when Malong was dismissed. Some members joined Malong’s new rebel movement, the South Sudan United Front/Army (SSUF/A), in April 2018 (Sudan Tribune, April 9, 2018). Like NAS, the SSUF/A also refused to sign the revitalized peace agreement. Malong’s attempts to run the movement from Kenya proved unsuccessful when the rest of the movement sacked him as leader in order to join the revitalized peace process (Sudan Tribune, October 8, 2018). [2]

Cirilo claimed to have seen documents showing the government was delivering weapons to Mathiang Anyoor by bypassing military supply lines. A government spokesman retorted that it was unfortunate that Cirilo was going “out of his mind” (Reuters, May 5, 2017).

Initial financing for the militia was provided by the chairman of the Jieng (Dinka) Council of Elders (JCE). The JCE is a regular target of Cirilo, who charged in his resignation letter that the elders had taken command of the SPLA to pursue an ethnic cleansing of South Sudan’s many other ethnic groups (VOA, February 14 2017).

In early January, the SSPDF accused NAS fighters under the command of General Luboron of killing 19 civilians in Yei River State. A spokesman for the NAS-allied People’s Democratic Movement (PDM) led by Hakim Dario accused Mathiang Anyoor of carrying out the killings as revenge for the loss of 15 militiamen in clashes with NAS forces in central Equatoria (Sudan Tribune, January 5). NAS insisted the SSPDF had taken out its anger on local artisanal gold miners after coming off second-best in a skirmish with NAS forces (Gurtong.net, January 4; Sudan Tribune, January 5). Further clashes between NAS and Mathiang Anyoor in the following days resulted in the reported death of 13 more civilians and seven members of the Mathiang Anyoor (Sudan Tribune, February 13).

Opposing the Peace Process

According to Cirilo, the existing system of governance in South Sudan is “nothing but a dictatorship in disguise.” The rebel leader has also criticized the failure to reform the security sector, “which is dominated by one ethnicity [i.e. the Dinka] out of 64 (Sudan Tribune, March 3).

In September 2018, the main warring parties in South Sudan signed a peace agreement in Khartoum, with Cirilo noticeably absent. A NAS spokesman explained the rejection of the revitalized ARCSS (R-ARCSS), sponsored by the regional Inter-Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD), by calling the document “a recipe for more conflict” (Sudan Tribune, September 1, 2018). [3] Cirilo’s NAS was joined by the PDM, the Pagan Amum Okiech led SPLM-Former Political Detainees (SPLM-FPD) and a number or armed groups in refusing to sign the agreement.

Cirilo became chairman in October 2018 of the South Sudan Opposition Alliance (SSOA), a largely Equatorian coalition of non-signatory groups. A rival SSOA coalition led by Gabriel Chang Changson favored the R-ARCSS. A reorganization of the non-signatory groups occurred in March, when the PDM left the SSOA in favor of another coalition, the National Alliance for Democracy and Freedom Action (NADAFA). [4] The rest of the SSOA formed the Cirilo-led South Sudan National Democratic Alliance (SSNDA).

Cirilo’s SSNDA consists of NAS, the National Democratic Movement (NDM) of Dr. Lam Akol Ajawin (Shilluk), the United Democratic Republic Alliance (UDRA) of Dr. Gatwech Koang Thich (who identifies himself as a research scientist at the United States Naval Air Warfare Center and a NASA research fellow) and a faction of the South Sudan National Movement for Change (SSNMC) led by Vakindi L. Unvu (Sudan Tribune, February 11). [5]

Green = Bahr al-Ghazal, Yellow = Upper Nile, Blue = Equatoria.

The greatest difference between the rival coalitions is that the SSNDA favors the redivision of South Sudan’s current 32 states to the 10 that existed at independence, while NADAFA favors a return to the traditional three states of South Sudan (Sudan Tribune, March 26). [6]

In November 2018, South Sudan Vice President Wani Igga warned that all non-signatory groups would be declared terrorist organizations at the end of an eight-month period. More recently, IGAD has confirmed there will be no renegotiation of the R-ACRSS and Cirilo turned down a personal meeting with IGAD’s special envoy, sending a delegation instead (East African [Nairobi], March 7; IGAD Press Release, March 14).

Conclusion

With IGAD now threatening sanctions against him, Cirilo has little chance of attracting international or even regional support for his wish to strike a more favorable peace deal. Lacking an external source of arms and ammunition, Cirolo’s NAS is now facing growing military pressure. With the regime and Machar’s SPLM/A-IO now reconciled (at least temporarily), the SSPDF joined with Machar’s forces in February to launch an offensive against NAS fighters in central and western Equatoria. In early March, there were reports that troops of the Uganda People’s Defense Force (UPDF) had crossed the border into Equatoria, where they were in combat with NAS elements (Uganda is a strong supporter of the Kiir regime) (Observer [Kampala], March 6). Though the advent of the rainy season may provide Cirilo with some respite, the rebel leader may have to ultimately choose between reintegration with the regime or the gradual annihilation of his movement.

Notes

[1] Names and acronyms for South Sudanese rebel movements tend to follow the dual pattern first established by John Garang’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A) to emphasize the existence and difference between the political (SPLM) and military (SPLA) wings of the movement.

[2] Malong has made many political alliances through mass-scale polygamy, having over 100 wives.

[3] IGAD, “Revitalized Agreement of the Resolution of the Conflict in the Republic of South Sudan,” Addis Ababa, September 12, 2018, https://www.dropbox.com/s/6dn3477q3f5472d/R-ARCSS.2018-i.pdf?dl=0

[4] A new faction of the PDM favoring the R-ARCSS was recently formed. The People’s Democratic Movement for Peace (PDM-P) is led by Josephine Lagu Yanga, daughter of Anya Nya leader Joseph Lagu.

[5] Another faction of the SSNMC, led by Bangasi Joseph Bakosoro, is a partner in the R-ARCSS (SouthSudanNation.com, January 3).

[6] Other NADAFA partners include the Workers’ Party of Upper Nile (WPUN – largely Nuer) and the Federal Democratic Party/Army (FDP/A) of Peter Gatdet Yak (Bul Nuer), the main suspect in the 2014 massacre of 400 non-Nuer people at Bentiu while acting as a SPLA-IO commander (Sudan Tribune, February 9).