Andrew McGregor

June 18, 2009

Though it has never been used in a terrorist attack, the supposed usefulness of the deadly poison ricin in such operations continues to generate headlines and terrorism charges, the latest coming in Durham County, England.

The Alleged Ricin Laboratory in Burnopfield

The Alleged Ricin Laboratory in Burnopfield

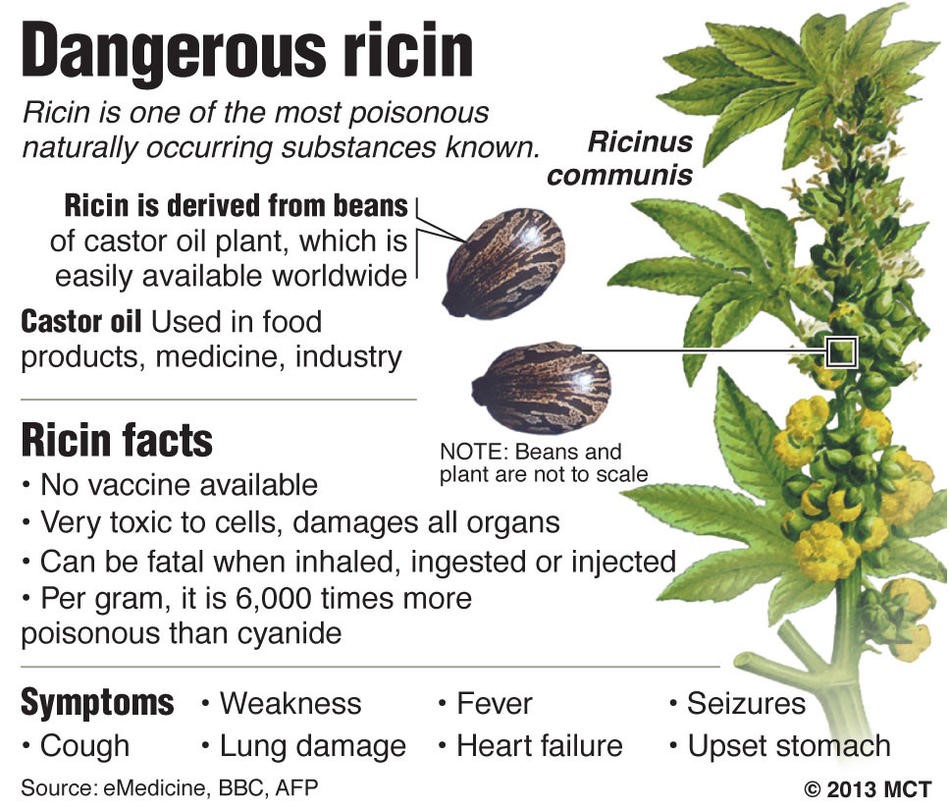

Dubious reports of ricin experiments conducted by Ansar al-Islam in northern Iraq in 2002 were followed by U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell’s assertions to the U.N. Security Council in February 2003 that an al-Qaeda laboratory in Georgia was creating ricin-based weapons under the direction of the late leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. The uneducated Zarqawi was given credit for doing in a rude shed what a number of well-funded and sophisticated Western weapons laboratories were unable to do in years of effort – weaponize ricin.

Since the poison cannot be absorbed by the skin, it is necessary to have victims either ingest or inhale the ricin. Since only the latter would be practical for a weapon, numerous attempts were made by weapons laboratories in the 20th century to aerosolize ricin, all meeting with disappointing results. Once Sarin gas and other nerve agents became available, further research into the use of ricin as a weapon was abandoned (apparently except for a KGB lab that developed a complex means of surreptitiously injecting ricin into a victim’s bloodstream – used only once on Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov in London in 1978).

A 41-year-old lorry driver and his 18-year-old milkman son were arrested under the UK’s Terrorism Act 2000 after June 2 raids on their homes in the Durham County villages of Burnopfield and Annfield Plain (Independent, June 5). Tests in a government laboratory in Edinburgh revealed traces of ricin in a sealed, airtight jam jar kept in a kitchen cupboard. The material was sent for further tests at the Ministry of Defence establishment in Porton Down. Police assured the public that “no one is believed to have been exposed to the substance or be at risk of any potential ill-effects. We do not believe that there is any risk to public health” (Independent, June 5). According to Durham’s assistant chief constable, “This shows that the terrorist threat in the UK is real” (Times, June 6).

The London tabloid Daily Express reported that the traces of ricin in the jam jar were “intended for use as part of a biological weapon against blacks and Asians” (Daily Express, June 6). The tabloid failed to mention that no such weapon yet exists, nor did it suggest how the suspects, of limited means and education, were to develop such a weapon. Nevertheless, the “biological weapon” was being reported the next day in India under the headline, “UK poison plot against Asians, blacks, busted” (Times of India, June 7).

Britain’s Independent linked the poison to al-Qaeda without mentioning the fascination right-wing extremists have with ricin, surely more relevant in the case of two alleged white supremacists. To underscore the alleged threat, the newspaper stated ricin as the agent used in the March 1995 attack on the Tokyo subway by the Aum cult that left 12 dead, when in fact the agent was Sarin gas (Independent, June 5).

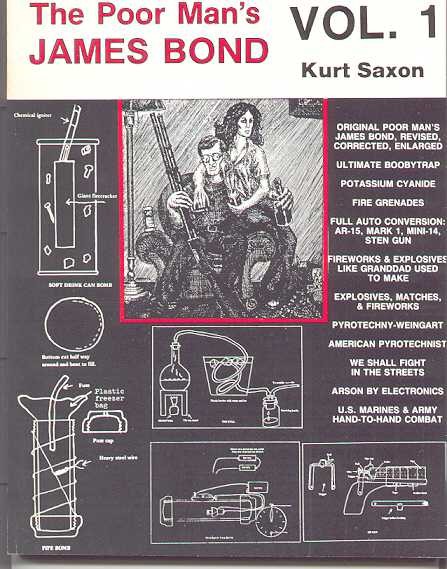

The 18-year-old suspect, Nicky Davison, was charged with possessing information useful to committing a terrorist act on June 9 and released on bail (BBC, June 9). The manual police described as containing information and instructions on the use or production of firearms, explosives and chemicals was a volume of The Poor Man’s James Bond, a four volume work by Kurt Saxon directed at American survivalists and militia members. First published in the 1970s, the volumes describe how to manufacture weapons, set booby traps, make explosives and develop poisons, including ricin. Davison has been charged with disseminating the work, though it is easily available from book-retailing websites and right-wing extremist sites alike (Northern Echo [Darlington], June 13).

The 18-year-old suspect, Nicky Davison, was charged with possessing information useful to committing a terrorist act on June 9 and released on bail (BBC, June 9). The manual police described as containing information and instructions on the use or production of firearms, explosives and chemicals was a volume of The Poor Man’s James Bond, a four volume work by Kurt Saxon directed at American survivalists and militia members. First published in the 1970s, the volumes describe how to manufacture weapons, set booby traps, make explosives and develop poisons, including ricin. Davison has been charged with disseminating the work, though it is easily available from book-retailing websites and right-wing extremist sites alike (Northern Echo [Darlington], June 13).

Earlier this month a small pile of white powder found on a table near the ROTC office at Utah’s Salt Lake University caused a small panic due to fears it may have been ricin. Over 200 people were ordered out of the building while National Guard units and Hazmat crews tested for ricin. The powder was also tested for anthrax, radioactivity and various biological viruses, all coming up negative. Early reports indicated the two teaspoons of powder looked similar to baby formula (KUTV.com [Salt Lake City], June 4; Salt Lake Tribune, June 4; Deseret News [Salt Lake City], June 13).

And in Washington State a man has been charged with trying to poison his wife with ricin after traces were found in her urine. The suspect explained to police he had bought the ricin to exterminate moles in the family yard (UPI, June 9). Though newspapers are often fond of noting ricin is 6,000 times more poisonous than cyanide, most internet recipes for homemade ricin from castor beans produce, at best, a highly diluted concentration of ricin that would need to be consumed in large amounts to create a fatal dose.

This article first appeared in the June 18, 2009 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor