Andrew McGregor

September 29, 2010

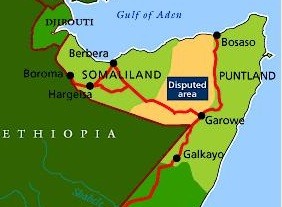

No roads penetrate the mountains of the Galgala district of Puntland’s Bari Region. Though it lies almost directly south of the steamy and bustling port of Bosaso, Puntland’s commercial capital, the moderate climate and cave-riddled hills of the relatively inaccessible Galgala region form a natural base for guerrilla operations. Control of the area has become a source of conflict in recent years after mineral exploration efforts uncovered a rich trove of various minerals in high demand on international markets.

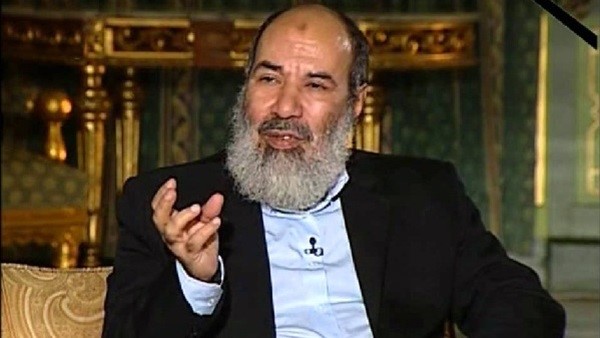

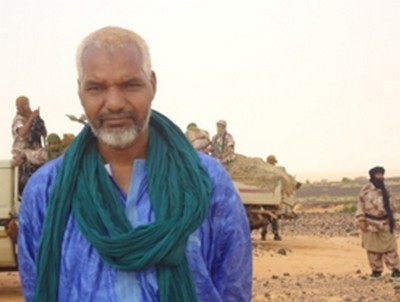

Efforts by the regional administration of Puntland (a semi-autonomous region of Somalia) to introduce resource exploitation into the area has resulted in a local resistance movement that may have morphed into an Islamist jihadi movement under the command of local Islamist Shaykh Muhammad Sa’id “Atam.” Puntland declared regional autonomy in 1998 to create a stable administration separate from the political chaos and violence engulfing Mogadishu and southern Somalia. The administration is dominated by the Majarteen clan.

Efforts by the regional administration of Puntland (a semi-autonomous region of Somalia) to introduce resource exploitation into the area has resulted in a local resistance movement that may have morphed into an Islamist jihadi movement under the command of local Islamist Shaykh Muhammad Sa’id “Atam.” Puntland declared regional autonomy in 1998 to create a stable administration separate from the political chaos and violence engulfing Mogadishu and southern Somalia. The administration is dominated by the Majarteen clan.

Shaykh Atam’s Background

Shaykh Atam, a member of Puntland’s minority Warsangeli clan (a branch of the Darod), is alleged to have been part of the al-Itihaad al-Islamiya (AIAI) forces under Shaykh Muhammad Haji Yusuf that fought the Ethiopian military incursion in southern Somalia’s Gedo region in 1996 (Frontier FM [Nairobi], August 13). As well as being a respected Islamic scholar, Shaykh Atam has been described as educated, disciplined and charismatic. His native Galgala region was once part of the Warsangeli Sultanate that ruled the area from the 13th to 19th centuries.

A known arms-dealer believed to have ties with the arms trade in Yemen, Shaykh Atam equipped a local armed group that resisted efforts by Australian firm Range Resources to carry out resource exploration in the Galgala region in 2006. The ad hoc militia succeeded in driving the exploration company and its security services guard from the area. Shaykh Atam has maintained his militia since and is reported to wield influence in the area through funds provided by arms sales, his advocacy of Shari’a and his ability to play on clan differences with Puntland’s majority Majarteen clan to alienate locals from the regional administration, which normally has only the slightest presence in the area (Reuters, July 28). Shaykh Atam’s militia is sometimes referred to locally as the “Natural Resource Troops” or “The Defenders of Sanaag Resources” (Galgala News Agency, July 31; August 17).

A report issued by the UN Monitoring Group in Somalia in 2008 claimed that information had been received indicating that Shaykh Atam was “aligned with al-Shabaab and may take instructions from Shabaab leader Fu’ad Muhammad Khalaf “Shangole.” The reports also suggested that his forces received supplies of weapons from Yemen and Eritrea. [1]

Clashes Begin

On July 26 Shaykh Atam’s forces attacked Puntland security checkpoints in the Karin district of the Bari region, killing one soldier. Security forces responded with a mass attack on insurgent bases in the mountains (Radio Gaalkacyo, July 26). The next day, Shaykh Atam told a news conference that he intended to continue fighting until his movement took control of the Puntland commercial center of Bosaso and implemented Shari’a there (Radio Shabelle, July 27). He also said the attack was a response to the regional administration’s blockade of supplies to the region (Radio Garowe, July 29).

Shaykh Atam’s militia clashed with security forces again on August 8 (Miisaanka.com, August 9). Al-Shabaab media relayed a report from the militants that claimed the capture of ten named members of the security services (Radio Andalus, August 8). Heavy fighting continued on August 9 near the Galgala town of Karin, with a reported 18 insurgents killed and some 20 wounded security personnel and insurgents arriving at a Bosaso hospital for treatment (Radio Horseed, August 9; Dayniile Online, August 10). General Abdisamad Ali Shire, commander of the Puntland security operations in the region, vowed to crush the insurgents, but military moves to secure important roads in Bosaso led to rumors that Shaykh Atam’s forces had already entered the city (Shacabkha.net, August 9; Somali Memo, August 9). While General Ali Shire issued threats, Puntland Security Minister Yusuf Ahmad Khayre was offering an amnesty to the insurgents if they would withdraw from the fighting even as other government officials said the fighting was spreading to other villages (Dayniile Online, August 10; Horseed Radio, August 9). Shaykh Atam told a sympathetic media source; “We are not here to provoke anyone; however, if the forces in western Bari Region attempt to provoke us with an attack, we will teach them a lesson” (Dayniile Online, August 10). By August 11, senior Puntland commanders were claiming to have seized the last of Shaykh Atam’s bases, though one of his lieutenants, Abdikarim Ahmad Beynah, insisted that the militants were in fact besieging the security forces (AFP, August 11). Shaykh Atam also accused the security forces of burning farms and torturing residents (Dayniile Online, August 10).

While traditional elders in the Bari region tried to mediate between the regional administration and Shaykh Atam’s group at first, the heavy-handed response of the security services (including the burning of farms and forcing women to remove the jilbab, an Islamic covering that reveals only the face and hands) led some elders to call for an uprising against the regional administration by mid-August (Shabelle Media Network, August 16).

Fighting flared up again on August 20 when Shaykh Atam’s fighters launched an attack on security forces inside Galgala village (Mareeg.com, August 20). Additional forces and weapons belonging to the Puntland Intelligence Service (PIS) and the Puntland Paramilitary were rushed to the Galgala region on August 22 while a committee of elders attempted to restart peace negotiations (Voice of Mudug, August 22; Galgala News Agency, August 26). Apparent differences with the government over the conduct of the fighting in the Galgala mountains led to the resignation of Puntland military chief Colonel Sa’id Abdi Farah “Tutaweyne” (Radio Gaalkacyo, August 22; Raxanreeb, August 22). After a brief lull, ten officers and civilians were killed in a new outbreak of fighting in the Bari region on September 12 (Mareeg.com, September 13).

Tactics

A report on a pro-Islamist website pointed out that the Puntland forces from Garowe and Bosaso lacked the necessary “skill, patience and special training” to fight effectively in the mountains of the Bari region, elements possessed by Shaykh Atam’s local forces, well trained in guerrilla warfare (Somali Memo, August 13). It was an assessment shared by Shaykh Atam in a mid-August interview; “I am operating from my backyard [laughing] and thanks to God none of our militiamen was hurt. These people [i.e. the security forces] are moving like animals, firing blank shots while we are firm on the ground because we know the terrain. We do not just fire unless we are sure of what we are firing at… The people who are fighting are members of the local community who took up arms against injustice of displacement, burning down houses, killing the young and the elderly as well as poisoning wells and other sources of water” (Frontier FM [Nairobi], August 13).

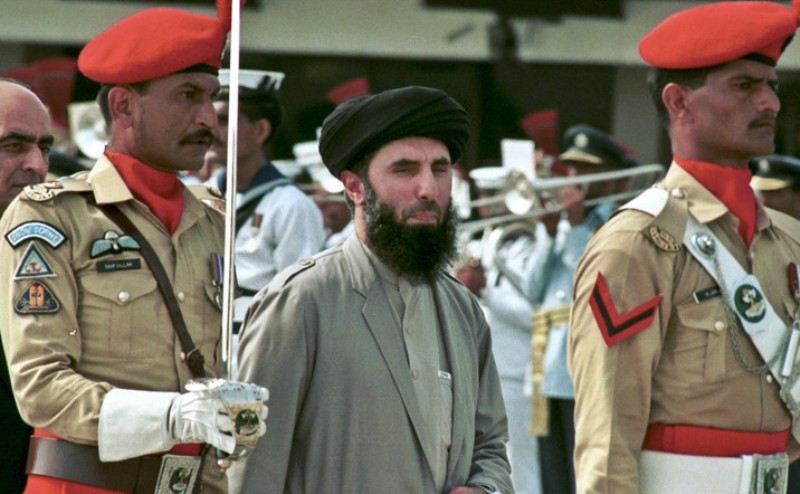

Puntland Government Troops on Operations in Galgala

Puntland Government Troops on Operations in Galgala

After losing his main bases to Puntland security forces, Shaykh Atam announced a change in tactics on August 14. Rather than trying to defend static positions, the insurgents would now rely on “hit and run methods” (Radio Gaalkacyo, August 14). An example of the new tactic had already been displayed two days earlier, when a hit and run attack on a Puntland security forces base in Bari region was repulsed with the loss of two government soldiers and at least four insurgents (AFP, August 13). Shaykh Atam’s militia typically deploys small arms, mortars and rocket-propelled grenades. It has also used improvised explosive devises (EIDs) to harass security forces and interfere with their supply lines (Shabelle Media Network, August 17; Raxanreeb.com, August 25; Somaliland Press, August 20).

A Battle for Resources?

The current conflict in Galgala has its roots in a 2006 effort by the regional administration to begin resource exploration in the area without local consultation and outside of any existing constitutional framework for such activities. Armed resistance led by Shaykh Atam to attempts by Puntland security forces to force their way into the area led to numerous deaths and the withdrawal of the Range Resources exploration team.

The region was the subject of intense exploration efforts in the early 1990s by Conoco and Phillips Petroleum, but the dissolution of effective government in Somalia after the overthrow of President Si’ad Barre in 1991 led to these firms abandoning their concessions.

Australia’s Range Resources signed a controversial exploration deal with the Puntland administration of Mohamud Muse Hersi “Adde” in 2005. A dispute with then-TFG President and Puntland native Abdullahi Yusuf over the legality of other Puntland resource deals led to the resignation of TFG Prime Minister Ali Muhammad Gedi in October 2007.Yusuf had at first said Puntland had no authority to negotiate such deals outside the framework of the TFG, but a reversal in his stance led to the dispute with Gedi. The resource deals played a large part in the brief creation of the self-proclaimed Warsangeli-dominated Maakhir State (based roughly on the borders of the old Warsangeli Sultanate) between 2007 and 2009.

After being repulsed by the Galgala militia, Range Resources brought in Canadian-owned Africa Oil Corporation (formerly Canmex) as a joint-venture partner in developing Puntland’s oil and mineral wealth in 2007. The election of Abdirahman Muhammad Farole, an Australian citizen, as Puntland’s president in January 2009 marked the beginning of Range Resource’s renewed efforts to conduct oil and mineral exploration operations in Puntland.

Galgala and other parts of the Bari region are above the Majiyahan Ta-Sn Deposit, a zone rich in minerals such as Albite, Quartz, Microcline, Tantalite, Tapiolite, Cassiterite, Spodumene and Muscovite. Some of these minerals are used to produce highly pure concentrations of lithium carbonate, a key component of batteries.

In May 2008 there were reports that the foreign exploration firms had assembled their own 250-man militia, armed with 50 of Somalia’s ubiquitous “technicals,” armored pick-up trucks equipped with a heavy machine gun or anti-aircraft weapons on the flatbed (Garowe Online, May 21, 2008).

The Regional Response

Though the Transitional Federal Government (TFG) in Mogadishu has expressed alarm over the outbreak of violence in Galgala, it has no forces available to assist in the repression of Shaykh Atam’s movement. TFG Minerals and Water Resources Minister Abdi Hasan Awale Qeybdid suggested instead that the government-aligned Ahlu Sunnah wa’l-Jama’a Sufi militia send forces to the region (Markacadey.net, August 9). TFG Member of Parliament Asha Ahmad Abdalla claimed that President Farole was conducting atrocities in his effort to secure Galgala’s mineral resources, for which he had already accepted payment from Western companies. She also accused the TFG of sending arms to the Puntland security forces to assist in this campaign (Dayniile Online, August 16).

Somaliland’s Interior Minister, Dr. Muhammad Abdi Gabose, declared that Somaliland (a self-declared but unrecognized state neighboring Puntland) had not devised a strategy to deal with the Galgala militants, whom he described as “a threat to Somaliland whether they are defeated by Puntland or not… If they are defeated, their remnants can commit acts of terrorism inside Somaliland” (Garowe Online, September 8). The Minister’s remarks indicated that Hargeisa regards the militants as an outgrowth of the Islamist insurgency in southern Somalia rather than a home-grown resistance to efforts by the Puntland administration to exploit the resources of the Galgala region. Even though Somaliland is engaged in a low-level border conflict with Puntland over the city of Los Anod and the regions of Sool, Sanaag and Cayn, Abdi Gabose also appealed for greater security cooperation with Puntland (Garowe Online, August 13; Somalimirror, August 14). Somaliland claims Galgala is part of its eastern Sanaag province, a claim locals have used to assert that the Puntland administration is attempting to operate in areas outside its jurisdiction (Somaliland Press, February 15; August 20).

Addis Ababa regards Shaykh Atam’s forces as a wing of al-Shabaab; according to the Ethiopian Ministry of Foreign Affairs; “The ongoing fighting between Puntland forces and al-Shabaab is an indication that the threat posed by this group is not just limited to southern Somalia regions but to other parts of the country that are peaceful.” The ministry urged Puntland and Somaliland to cooperate in forming “a powerful force” to fight al-Shabaab (Dayniile Online, August 18).

Despite claims that the administration has Galgala under control, President Farole has also appealed for international assistance in putting down the revolt; “This war terrorists have launched on Puntland today will not be limited to this region. If the international community does not assist us, the war will spread all over the region. Indeed it has already reached Kampala” (AFP, July 26). Shaykh Atam has mocked President Farole’s requests; “He pleaded that the international community and women take up arms… We are self-sufficient and God is our shepherd because we have been attacked without provocation” (Dayniile Online, August 10). He suggested Ethiopia had denied a request by Farole for the intervention of the hated Ethiopian military; “Farole went looking for additional forces from the Ethiopian colonizers but they rejected his requests for fear that they might be afflicted with painful lessons similar to the ones in southern Somalia where they were engaged in jihad. We are now undertaking a jihad similar to that one and we will defend ourselves from anyone that attacks us” (Dayniile Online, August 16).

The Puntland Intelligence Service

The Puntland Intelligence Service (PIS), led by Colonel Ali Muhammad Yusuf “Binge,” is the strongest armed group in Puntland and has taken the lead in the fighting in Galgala. The security force is largely drawn from the Osman Mahmoud subclan of the Majerteen and was established in 2001. It has been a frequent target of suicide-bombings and assassinations directed by al-Shabaab, which intends to extend its influence into Puntland. The PIS owes much of its prominence in Puntland’s power structure to aid and assistance provided by the United States and Western intelligence agencies. In addition it is alleged to receive 50% of the state budget. It has been frequently accused of inciting clan warfare between Majarteen and Warsangeli in the Bosaso region and acting in a provocative fashion towards leaders of the Islamic community (Puntlandpost, March 25, 2009). In April 2009 the newly elected Abdirahman Muhammad Farole ordered the PIS to shut down its Bosaso office after numerous public complaints, but the PIS obtained an extension (Garowe Online, April 29, 2009). The clashes in Galgala will help cement the PIS presence in the region. The PIS is unpopular in Bosaso, where residents commonly refer to it as “Ashahaada la dirir,” i.e. “Those who fight against the unity of God” (Hiraan Online, August 18).

Farole has struggled since his election to establish his dominance over the powerful PIS. Matters came to a head in March when the President ordered the sacking of the PIS leader since 2004, Osman Abdullahi “Diyane.” [2] There were suggestions that Farole suspected Diyane of using his contacts with Western intelligence agencies to provide damaging information regarding Farole’s links to Puntland-based piracy to the United Nations. To emphasize his reforms of the organization, Farole also decreed that the PIS would be henceforth named the Puntland Intelligence Agency/Puntland Security Force (PIA/PSF) (Somaliland Press, March 14). However, this rather unwieldy moniker has failed to catch on and the organization is still commonly referred to as the PIS.

The PIS has also cooperated with Ethiopian security services by arresting and handing over leading members of the Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF), an ethnic-Somali separatist movement that has traditionally used Puntland as a cross-border refuge (Garowe Online, April 25, 2008; May 4, 2008).

The Information War

The director of Bosaso’s Radio Horseed, Abdifatah Jama Mire, was sentenced to six years in jail and a fine of $500 in August as a penalty for “interviewing and broadcasting views of people who are fighting the government” after conducting an interview with Shaykh Atam. Prosecutors had only asked for a three-year jail term (National Union of Somali Journalists, Nusoj.org, August 14). Abdifatah, who was not allowed legal representation, pointed out that an interactive interview with Shaykh Atam broadcast on the Paltalk network had already covered much of the same ground and had even been quoted by Puntland authorities to support their position that Atam was connected to al-Shabaab (Shabelle Media Network, September 4; Garowe Online, August 14).

On August 15, Puntland Information Minister Abdihakim Ahmad Guled banned local media from interviewing leaders of the insurgency or even commenting on official news reports of the fighting (Radio Gaalkacyo, August 16). VOA reporter Nuh Muse Birjeb was also banned from the region after interviewing Shaykh Atam. [3]

Al-Shabaab media outlets have taken up the cause of Shaykh Atam’s movement and its fight against “the apostate militia group that works for the Christian government of Ethiopia [i.e. the Puntland security forces]” (Radio Andalus, August 8).

Shaykh Atam – an Associate of al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda?

Soon after the fighting in Galgala began, al-Shabaab spokesman Shaykh Ali Mahmud Raage “Ali Dheere” announced that Shaykh Atam’s militia had no connection to al-Shabaab and consisted solely of local people; “It should not be [the case] that every time a group of Muslims fight against current regimes that they should be said to be part of al-Shabaab” (VOA Somali Service, July 29). Shaykh Atam also denied any involvement of al-Shabaab at the time.

A UN Secretary-General’s report earlier this month described the Galgala militants as “a clan militia… believed to have close connections to al-Shabaab.” The Puntland press presented this as validation of the government’s claims the insurgency in Bari region was being orchestrated by al-Shabaab (Garowe Online, September 15). [4]

Puntland administration security advisor Ahmad Husayn announced on August 13 that the administration had evidence that foreign fighters had joined Shaykh Atam’s group, but did not provide any proof (Radio Gaalkacyo, August 13). Shaykh Atam has denied the presence of any foreign fighters in his group at almost every opportunity. One recent report claimed hundreds of Islamist fighters from southern Somalia had arrived in Bosaso to join the fight against the Puntland government, though this could not be verified (Dayniile Online, September 17).

Shaykh Atam has also received verbal support from Somalia’s Hizb al-Islam militia. The chairman of Hizb al-Islam in the Banaadir region (which includes Mogadishu), Ma’allin Hashi Farah, issued a statement on August 12 calling on “the mujahideen, wherever they are, to support their brother Shaykh Atam, who is battling Puntland. I encourage fighters loyal to Hizb al-Islam to travel there” (Kismaayo News Online, August 12; Dayniile Online, August 12).

Shaykh Atam claims that the people of his region have never had any relations with the Puntland administration, which he regards as an “apostate party.” It was their decision to “invade” Galgala that led to the fighting – he and his militia have no responsibility for the conflict. Shaykh Atam’s explanation of the fighting has little of the incendiary Islamist rhetoric that pervades al-Shabaab’s provocative insistence on the conquest of areas of Somalia outside their control in the interest of forming an Islamic Caliphate. According to Shaykh Atam; “Our interest is to defend ourselves. Any Muslim person would love to live in freedom and with his religion – and also to defend yourself against any enemy that invades you… We are not intending to invade anyone; however, we have been invaded and we also defended ourselves and we will continue fighting” (BBC Somali.com, August 10). Puntland’s General Abdullahi Ahmad Ja’amah “Ilka Jiir” denied claims the administration was fighting clan militias in Galgala; “We are fighting terrorists and the people must understand that the government is there to defend them from any attack (Garowe Online, August 21).

While Shaykh Atam denies the Puntland administration’s so-far unsubstantiated claims of the presence of al-Qaeda members and foreign fighters in his militia, he has made his own claims of an American and Ethiopian presence in the Puntland security forces attacking the area. In particular he says three American officials arrived in the wake of the Puntland security forces to take pictures of the battle-sites, including damaged mosques, madrassas and an Islamic library burned down by Puntland forces (BBC Somali.com, August 10; Dayniile Online, August 10).

Shaykh Atam has been vague about his relationship to al-Shabaab, making any possible relationship to the movement more a matter of interpretation than assertion. Typical is his response to a BBC Somali service reporter’s question regarding his ties to al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda:

There is nothing like that. Al-Shabaab has already said that we have no relations except the Islamic brotherhood ties between us… We are Muslims and if being a Muslim [means] you are a member of al-Shabaab or al-Qaeda – so be it. We are Muslims, who are opposed to those against the religion… Our ideology is based on Islam. We never carried guns to fight – but we were invaded and forced to fight” (BBC Somali.com, August 10).

The Shaykh was a bit more explicit in a Paltalk teleconference but still stopped short of clearly identifying his group as a wing of al-Shabaab; “We are al-Shabaab and al-Shabaab are us; we are joined in the same struggle to fight for the establishment of an Islamic state in Somalia” (Horseed Media, July 27).

Conclusion

Shaykh Atam’s revolt may be viewed as an example of a clan-based conflict over resources quickly evolving into an Islamist insurgency under the political/religious conditions developed during the “war on terrorism.” Though the conflict may have local origins, as an Islamist seeking the rule of Shari’a in the Galgala region, Shaykh Atam may find natural ideological if not material allies in al-Shabaab. There is little evidence yet to suggest that the Galgala rebellion is a new front in al-Shabaab’s struggle to bring the northern regions of Puntland and Somaliland under its control, but folding the conflict into the larger “war on terrorism” allows the Puntland administration to use extraordinary measures to consolidate its control of the region without fear of international approbation.

Shaykh Atam’s belief that the regional administration of Puntland is apostate and in need of elimination places him firmly in the takfiri camp of the Salafi-Jihadist movement that includes al-Shabaab and al-Qaeda. The shift from local militia to Islamist movement leaves little room for reconciliation with the Puntland administration. According to Shaykh Atam; “We can only engage in talk with Muslims who believe in the one God and in Prophet Muhammad as his messenger, but anti-Islamic people are apostates. The Prophet (p.b.u.h.) said that whoever changes his religion should be fought” (Frontier FM, August 13).

Notes

- Report of the UN Monitoring Group on Somalia submitted in accordance with resolution 1811 (2008), http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N08/604/73/PDF/N0860473.pdf?OpenElement

- Presidential Decree No. 27, March 12, 2010, http://www.puntland-gov.net/viewnews.asp?nwtype=News&nid=News201331312101644706

- VOA Somali, August 10, 2010, http://www.voanews.com/somali/news/somali/Attam-oo-ka-hadlay-qabsashada-Galgala-100346509.html

- For the Secretary-General’s report, see http://wwww.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900SID/EGUA-89AUFT?OpenDocument

This article first appeared in the September 29, 2010 issue of Militant Leadership Monitor