Andrew McGregor

November 6, 2018

Low-intensity conflicts can be among the most resistant to resolution. A case in point is the 36-year separatist struggle in Casamance, the southern region of Senegal. While the conflict has veered between ceasefires and flare-ups, one man, Salif Sadio, has dedicated himself to keeping the separatist cause alive through his leadership of Atika, the armed wing of the Mouvement des forces démocratiques de Casamance (MFDC). The price of his struggle has been thousands killed and the devastation of the local economy.

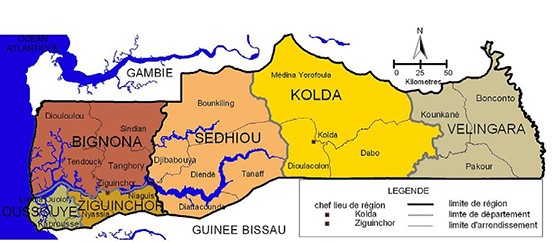

The conflict in Casamance has much to do with its physical separation from the rest of Senegal by the small nation known as “The Gambia.” The Gambia, which became independent in 1965, was a former colony of the UK, while the area surrounding it was French territory which became independent as the nation of Senegal in 1960. The region south of The Gambia is known as Casamance and was integrated with Senegal by an eastern land connection that left The Gambia surrounded by Senegal.

An attempt at union between Senegal and The Gambia in 1982 (the Senegambian Confederation) brought economic benefits to Casamance, but the local economy was hit hard when the confederation collapsed in 1989. Administratively, Casamance was divided by the government into the districts of Ziguinchor to the west and Kolda to the east in the 1980s in the hope of ending references to “Casamance.” [1]

The main peoples found in Casamance are Mandinke, Pulaar and Jola (or Diola). The dominant ethnic group in Senegal is the Wolof, whose central role in the administration is resented by many Jola, who make up only 4% of Senegal’s population.

By the 1980s, the Christian and Animist Jola people of Casamance began to speak of separation from an exploitative Musliim regime in the Senegalese capital of Dakar (Senegal is 92% Muslim). The Jola, representing roughly a third of the Casamance population, dominate the ranks of the MFDC, though many Jola see the movement as inhibiting development and have nothing to do with the separatists (Le Monde, June 19, 2012).

Salif Sadio and the MFDC are angered by Senegal’s planned expansion of its resource sector, which will include exploitation of oil, gas, zircon and other minerals in Casamance. The MFDC claim the proceeds of such work go directly to the national government in Dakar without any benefit to the people of Casamance. Sadio also claims these projects will cause environmental devastation, though his own movement is accused of partaking in the massive ongoing deforestation of Casamance.

The MFDC

The MFDC was founded in 1982 by Father Augustin Diamacoune Senghor, though a movement for regional autonomy had existed since 1947. [2] Atika was formed three years later in 1985. Oil was discovered offshore in Casamance in the early 1990s, emboldening the separatist movement, but bringing on massive government repression of separatist activities. [3]

The first split in the MFDC dates back to 1992, when northern elements were prepared to negotiate a settlement, but Jola-dominated southern elements, such as those led by Salif Sadio, were determined to offer armed resistance to the Senegalese state. [4] Dakar’s military response to the insurgency was to drive the MRDC into neighboring Guinea-Bissau with such intensity that it nearly created a border war with that nation, as well as creating alienation in the local population. [5]

Early Years

In 1998, Sadio crossed into Guinea-Bissau and joined the military rebellion led by Brigadier General Ansumane Mané. The Brigadier (then chief-of-staff) had been suspended on suspicion of trafficking arms from Bissau-Guinean arms depots to the MFDC separatists in Casamance. The MFDC had already been engaged in bloody clashes with Bissau-Guinean troops along the border in January 1998 and were ready to support a change of regime. In the civil war that followed Brigadier Mané’s June 1998 coup, the MFDC fought alongside the vast majority of the Bissau-Guinean army which sided with Mané against the government of President João Bernardo Vieira. Military intervention by Senegal and Guinea led to a ceasefire and formation of a government of national unity in February 1999, but President Vieira survived only until May, when a second coup overthrew him. In the meantime, Sadio’s support for the military rebels had solidified connections that would serve him well in the future.

Determined to exterminate the MFDC, the Senegalese military shelled Ziguinchor, the largest city in Casamance, in 1999, even though it could hardly be called a MFDC stronghold. The resulting civilian casualties and displacement of residents did little to encourage loyalty to the state.

The Casamance Rebellion

Diamacoune agreed to a peace agreement in 2004 that called for integration of MFDC fighters into the Senegalese security services and economic development in Casamance, but other factions of the MFDC rejected the agreement and continued their armed movement for separation. The agreement eventually collapsed in August 2006.

In early 2006, the leaders of other MFDC factions condemned Sadio for his unwillingness to join the peace process and threatened to “outlaw” him. [6] In the following year, Sadio purged most of the older commanders in his group, whom he suspected of moderate tendencies, and replaced them with more aggressive younger commanders. [7]

After several years of avoiding direct confrontations with the Senegalese Army, the MFDC stepped up attacks on the military in late 2006 after Moroccan troops arrived to assist in a de-mining campaign. The MFDC, which uses mines as an important part of their arsenal, suspected that Dakar had brought in the Moroccans to assist in an effort to capture Salif Sadio. [8]

In March 2006, the president of Guinea-Bissau, João Bernardo Vieira (who had returned from post-coup exile in 2005 to be re-elected as president), with the encouragement of his rival and military chief-of-staff General Baptista Tagme na Wale, decided that it was necessary to expel Sadio’s forces from Guinea-Bissau to help further peace efforts in neighboring Senegal. Though military operations succeeded in driving Sadio from his base in Guinea-Bissau, Sadio orchestrated an orderly withdrawal into Casamance, mining roads behind him and mounting attacks on Senegalese garrisons near the border to allow his men to retake old MFDC bases in the Sindian region of north Casamance, close to the border with The Gambia. [9]

The charismatic Abbé Diamacoune died in Paris in January 2007, but he had already lost control of the movement he founded, which split before his death into three major factions led by Sadio, Caesar Badiatte, and Mamadou Niantang Diatta. With fighting between the groups unsettling the entire region, the Senegalese military sent armor and heavy weapons to Casamance for an offensive focused on Sadio’s Atika faction, the most intransigent of the three. [10]

Sadio found refuge in The Gambia, ruled by President Yahya Jammeh, a Jola Muslim known for corruption and his use of assassination squads who took power in a 1994 coup d’état. In 2007, several MFDC leaders claimed the government of The Gambia was supplying arms to MFDC “hard-liners” such as Salif Sadio. [11]

Heavy fighting broke out around Casamance’s main city of Ziguinchor in August 2008 as the MFDC launched a series of raids to steal the bicycles, mobile phones and identity papers of local residents. Farmers were warned by the militants that if they returned to their fields they would be treated as army informants (IRIN, August 26, 2009).

After relations with The Gambia’s President Jammeh soured in 2009, Sadio shifted his base back to Guinea-Bissau, where he enjoyed a good relationship with a former comrade-in-arms, Captain Zamora Induta, the new military chief-of-staff and a veteran of the military rebellion of 1998-1999. [12]

A shipment of Iranian arms was found hidden amidst building materials on a ship that arrived in Lagos harbor in October 2010. Investigators believed the arms were intended to be shipped to The Gambia and then distributed to the MFDC. The incident resulted in Senegal recalling its ambassador to Iran (BBC, December 15, 2010). Other arms shipments might have made it through; Senegalese troops were surprised in December 2010 when MFDC forces using newly acquired equipment such as mortars, rocket launchers and Russian-made “Dushka” machine guns killed seven soldiers near the town of Bignona (RFI), December 28, 2010).

Fighting flared up again in December 2011, when at least 12 Senegalese soldiers were killed in clashes with the MFDC (SAPA, December 21, 2011). The election of Macky Sall as Senegal’s president in March 2012 opened new opportunities for a negotiated settlement of the Casamance issue. Talks with Salif Sadio’s representatives began in Rome in October 2012 under the auspices of the Community of Sant’Egidio, a Vatican-aligned charity specializing in conflict mediation. Two months later Sadio’s faction released eight hostages in a gesture of good-will (AFP, November 10, 2013).

When Macky Sall became Senegal’s president in 2012, one of his first promises was to bring a swift end to the Casamance conflict. If the promise sounded familiar, it was because his predecessor Abdoulaye Wade had promised in 2000 to resolve the crisis in 100 days through a combination of disarmament, demining and large agricultural projects in Casamance (al-Jazeera, February 14, 2012).

To keep the peace, President Wade supplied the MFDC factions with cash and rice. Sadio was reported to have used the money to buy weapons rather than distribute it to his fighters as intended (Seneweb.com, April 10, 2015). Nonetheless, by May 1, 2014, Sadio was ready to declare a unilateral ceasefire, still officially in place today.

The MFDC in The Gambia

Back in The Gambia, President Jammeh’s long run as president came to an end with an election loss in December 2016, but Jammeh refused to step down to allow Adama Barrow, the surprise winner of the election, to take power.

After his election loss, Jammeh was reported to have recruited mercenaries from several West African regions, including MFDC fighters, to prepare for an expected intervention to remove Jammeh by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) (Liberian Observer, January 19, 2017). Senegal took leadership of the ECOWAS operation and Jammeh fled Gambia on January 21, 2017.

As relations between Senegal and The Gambia improved under President Adama Barrow, Omar Sadio, a son of Salif Sadio who had served in the Gambian Army since 2005, was relieved of his rank and arrested (Gambia Echo, October 12, 2017). His detention appeared to have been part of a sweep of suspected Jammeh loyalists in the military, many of whom were brought in by the ex-president from neighboring states in the belief they would be personally loyal to the president and not identify with Gambians.

Slaughter in the Forest – A Battle for Resources

The ceasefire was threatened this year by the January 6 execution-style killing of 14 alleged loggers in the Bayotte Forest of Casamance. Many of the hardwoods found in the forests of Casamance, such as teak and rosewood, are of high value. Much of the wood taken illegally is shipped through The Gambia on to China, where it is highly prized (AFP, January 24).

Casamance Timber Headed for Export (Daniel Glick)

Casamance Timber Headed for Export (Daniel Glick)

Two armed men were killed by security forces in separate clashes shortly after the massacre as Senegalese troops rounded up suspected militants. Sadio promptly denied any involvement by his faction of the MFDC. In an interview recorded at his forest base near the Gambian border, Sadio insisted “The killing was only a pretext that served the Senegalese army to trigger military operations in Casamance.” He demanded the release of “innocent civilians” detained in the sweeps and warned that the MFDC’s unilateral ceasefire might end if the operations continued (Jeune Afrique/AFP, January 24).

Sadio, who has accused the army of cutting timber in protected areas, admits his men beat loggers and even burn their trucks, but insists they have never killed loggers (Jeune Afrique/AFP, January 24). Sadio rejects allegations that he cooperates with The Gambia to extract valuable hardwoods from Casamance (Senenews.com, January 24).

An emerging irritant is the plan by Australian firm Astron Zircon to dig out sand dunes on the Casamance coast to remove deposits of zircon, a gemstone with many applications. Locals fear the removal of these natural barriers to the sea will result in the salinization of farmland and drinking water (DakarActu, June 27) The government in Dakar insists the Zircon extraction will provide economic benefits to Casamance, but Sadio has warned that “the exploitation of zircon represents a declaration of war. Many times we have agreed with Senegal not to touch anything and wait for the settlement of the conflict.” [13]

Conclusion

Salif Sadio’s faction of the MFDC constitutes a destabilizing force in the Senegal/Gambia/Guinea-Bissau region. Prospects for a negotiated settlement in Casamance have grown remote with the split of the MFDC into three mutually suspicious factions. A military solution without coordinated regional cooperation is just as elusive, with MFDC fighters currently slipping across international borders whenever they are pressured.

Senegal’s government has tried different means of dealing with the MFDC, including pay-offs and military repression, but little effort has been put into addressing the social, economic and environmental underpinnings of Casamance separatism. Without such efforts, hardliners like Salif Sadio will continue to draw support from disaffected residents, particularly amongst the Jola ethnic group, whose culture and grievances have attracted little attention from government officials tasked with dealing with them.

Notes

- Aïssatou Fall, Understanding the Casamance Conflict: A Background, KAIPTC Monograph no. 7, December 2010, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B40UDxMwk8FATGZ4U19pMk5ZNGs/view

- Ibid

- Michael E. Brownfield and Ronald R Charpentier, “Assessment of the Undiscovered Oil and Gas of the Senegal Province, Mauritania, Senegal, The Gambia, and Guinea-Bissau, Northwest Africa,” U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2207–A, October, 2003, https://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/b2207-a/b2207-a.pdf.

- Wagane Faye, The Casamance Separatism: From Independence Claim to Resource Logic, Naval Postgraduate School Thesis, Monterey California, June 2006, http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a451368.pdf

- Ibid

- “MFDC Murders Casamance Deputy Prefect: Are Hardliners Trying to Sabotage the Peace Process?” US State Department Cable 06DAKAR43_a, January 6, 2006, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06DAKAR43_a.html

- “Deterioration in the Casamance,” US State Department Cable 07DAKAR275_a, February 2, 2007, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/07DAKAR275_a.html

- “Casamance: Escalation in Rebel Attacks,” US State Department Cable 06DAKAR3016_a, December 27, 2006, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06DAKAR3016_a.html

- “Casamance: Chief Rebel Stronger than Anticipated,” US State Department Cable 06DAKAR1005_a, April 26, 2006, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06DAKAR1005_a.html. Three years after the offensive against Salif Sadio, the rivalry between General Na Waie and President Vieira proved fatal. The general was assassinated in a bomb attack on March 1, 2009; the next day, Vieira, who had turned his nation into a “narco-state,” was hacked to pieces by machete by troops loyal to the general (The National [Abu Dhabi], March 7, 2009l; see also Anders Themnér, Warlord Democrats in Africa: Ex-Military Leaders and Electoral Politics, London, 2017.

- “Casamance: The 2004 Truce Has Ended,” US State Department Cable 06DAKAR2012_a, August 21, 2006, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/06DAKAR2012_a.html

- “The Gambia: Further Strains in Ties with Senegal over Casamance,” US State Department Cable 07BANJUL250, May 15, 2007, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/07BANJUL250_a.html

- “Senegal: War and Banditry in the Casamance,” US State Department Cable 09DAKAR948_a, July 27, 2009, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/09DAKAR948_a.html

- “Le MFDC réitère sa menace de reprendre les armes ,”August 30, https://www.podcastjournal.net/Le-MFDC-reitere-sa-menace-de-reprendre-les-armes_a25680.html

This article first appeared in the October 2018 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Militant Leadership Monitor.