Andrew McGregor

August 11, 2008

Sudan’s growing oil industry has already transformed the capital of Khartoum and has the potential to raise living standards throughout the country. The industry, dominated by Asian multinationals, nevertheless faces serious security threats from rebel movements unhappy with the conduct of foreign companies and the distribution of oil revenues.

Sudan has an estimated oil reserve of five billion barrels, making it an important player in an energy-hungry world. The reserves are part of the vast Central African Muglad Basin, which provides two main types of oil – Dar Blend Crude, which is typically sold at a discount due to its high acidity, and the higher quality heavy sweet Nile Blend Crude (APS Review Oil Market Trends, February 27, 2006). Sudan does not have the equipment, personnel, or experience to exploit its oil resource; foreign participation is thus essential. Oil production by Western oil companies was set to begin in the 1980s, but was halted because the outbreak of the Second Civil War made the work too dangerous. China, Malaysia, and India now control most of the Sudanese oil industry after filling the void in the 1990s.

Sudan has an estimated oil reserve of five billion barrels, making it an important player in an energy-hungry world. The reserves are part of the vast Central African Muglad Basin, which provides two main types of oil – Dar Blend Crude, which is typically sold at a discount due to its high acidity, and the higher quality heavy sweet Nile Blend Crude (APS Review Oil Market Trends, February 27, 2006). Sudan does not have the equipment, personnel, or experience to exploit its oil resource; foreign participation is thus essential. Oil production by Western oil companies was set to begin in the 1980s, but was halted because the outbreak of the Second Civil War made the work too dangerous. China, Malaysia, and India now control most of the Sudanese oil industry after filling the void in the 1990s.

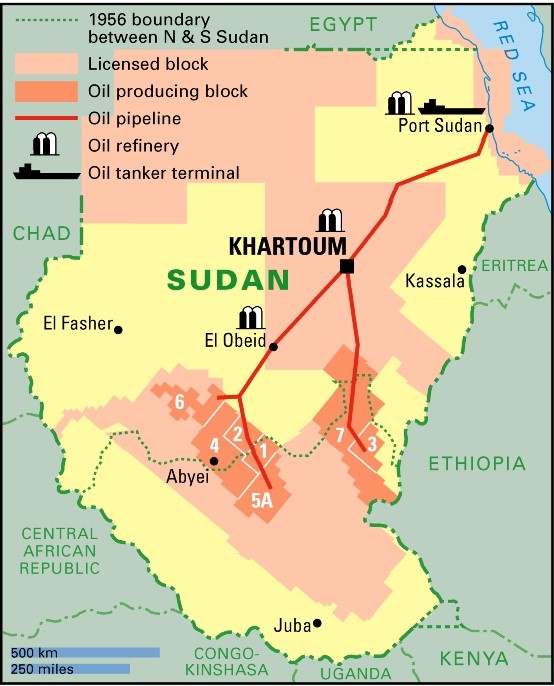

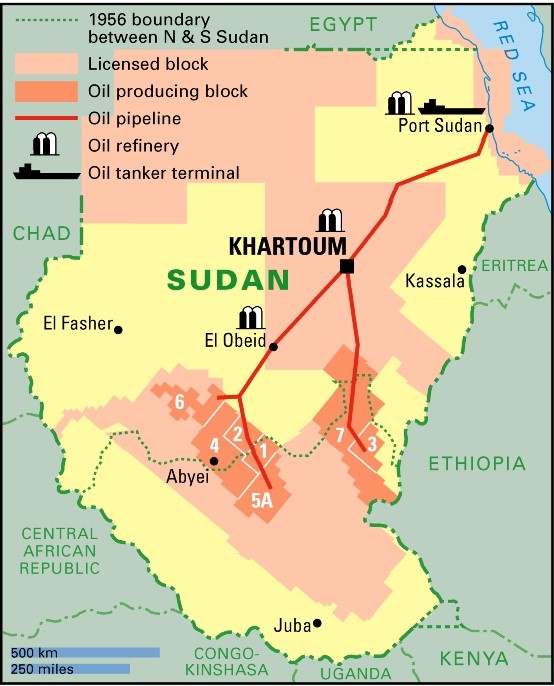

Most of the oil is found in the South Sudan, with smaller oilfields in the western province of Kordofan. Exploration is ongoing in east Sudan and ready to begin in north Darfur. Khartoum’s control of the South Sudan oilfields depends on the outcome of provisions of the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) between the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) and the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army/Movement (SPLA/M), the south’s largest rebel movement. The two signatories form the Government of National Unity (GoNU), which rules the country until the status of the South is determined by referendum in 2011.

The China Factor

Chinese involvement in Sudan’s oil sector began in 1995 when President Omar al-Bashir invited China to develop Sudan’s oil industry during a visit to Beijing (China Daily, November 3, 2006). China is now the world’s second-largest oil importer, with Sudan ranking somewhere between its fourth and sixth largest source of oil, according to various estimates (Saudi Arabia, Iran, Angola, and Oman are other major suppliers). Sudan currently pumps 500,000 bpd, with an estimated 200,000 bpd going to China, representing 6% of China’s daily supply (Reuters, January 22). According to an official of the Sudanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs, China has invested over $6 billion in the last decade in 14 oil projects (Sudan Tribune, November 5, 2007). In return, Beijing’s political support for Sudan at the UN Security Council and elsewhere is generally unwavering.

China’s quiet “arms for oil” exchange in the Sudan has angered rebel movements in Darfur, who have long accused Beijing of supplying the weapons used by Janjaweed militias and the regular Sudanese Army to slaughter civilians and destroy local infrastructure. It is estimated that as much as 90% of Sudan’s small-arms imports come from China, with many of these weapons reaching Darfur despite an international embargo on all parties involved in the conflict (AP, August 5). China has also supplied Nanchang A-5 ground attack aircraft (NATO name: Fantan A-5) and training for the pilots. The fighters operate out of the Nyala airbase in Darfur (BBC TV, July 14).

Darfur-Based Rebels Oppose China’s Oil Companies

China’s main opponent in Sudan is Darfur’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), a skilled guerrilla force capable of mounting long-distance attacks under a leadership drawn mostly from the Zaghawa tribe, which straddles the border between Darfur and Chad.

Last October JEM seized GNPOC facilities at the Defra oil field in South Kordofan as a warning to China to cease its military and political support for Khartoum. Five oil workers were taken hostage with the warning, “Our main targets will be oilfields” (Reuters, October 25; October 29, 2007). A group of JEM rebels tried to seize Chinese facilities at al-Rahaw in South Kordofan in November 2007. JEM claimed to have taken the site but the SAF insisted they were driven off. “Our attack is another attempt at telling Chinese companies to leave the country…We are implementing our threat of attacks against foreign companies, particularly Chinese ones, and we will continue to attack… Our goal is for oil revenues to go back to the Sudanese people and that is a strategic plan of our movement,” said JEM commander Abdul Aziz al-Nur Ashr, the brother-in-law of JEM leader Khalil Ibrahim (AFP, December 11, 2007). Ashr is currently standing trial on charges of terrorism and insurrection in Khartoum after being captured in JEM’s May raid on Omdurman (see Terrorism Monitor, May 15).

In December JEM claimed to have seized part of the Hejlij oilfield after defeating SAF troops (Reuters, December 11, 2007). JEM official Eltahir Abdam Elfaki said the Arab Messiriya tribe had joined JEM in their attacks on Chinese oil operations after becoming angered when they were included in a disarmament campaign (Dow Jones, April 15).

The Sudan Liberation Army/Movement (SLA/M – not to be confused with the SPLA/M), a mostly Fur Darfur rebel group led by Abdul Wahid al-Nur, has also threatened Chinese oil facilities. In an interview al-Nur told Dow Jones, “Oil companies are gravely mistaken if they think security agreements with the sole government in Khartoum are enough to protect their operations” (Dow Jones, December 8, 2007). In April a JEM official announced JEM “would love” to have Western oil companies replace Chinese firms: “We don’t want China. We want to expel them. We have the means… We are preparing new attacks” (Dow Jones, April 15).

Darfur’s National Redemption Front (NRF) and the SLA/M attacked the Abu Jabra oil field in west Kordofan in November, 2006, causing significant damage to the facilities (Sudan Tribune, November 26, 2006; AP, November 27, 2006). The NRF, drawn mostly from the Zaghawa tribe, has close ties to Chad and normally operates in northern Darfur.

China has supplied a 315 man military engineering team to the United Nations Mission in Darfur peacekeeping force. Last November JEM commander Abdul Aziz al-Nur Ashr stated, “Our position is clear, the Chinese are not here for peace and they must leave immediately… Otherwise, we will consider the Chinese soldiers as part of the government forces and we will act accordingly… China is complicit in the genocide being carried out in Darfur and the Chinese are here to protect their oil interests in Kordofan” (AFP, November 25, 2007).

The discovery of oil in Darfur was first announced by the Sudanese Minister of Energy and Mining in April 2005. China is eager to begin serious exploration in Block 12-A, located in northern Darfur. Discussions on security have been undertaken with Khartoum, which is insisting the SAF first establish secure conditions on the ground before exploration begins. Once established, Chinese oil facilities in the region will be guarded by troops of the SAF (Sudan Tribune, July 9). Saudi and Yemeni companies are also interested in working in Darfur.

Total SA’s Return to the South Sudan

Since Canadian Talisman Energy pulled out under domestic and international pressure in 2002, the oil industry in Sudan has been dominated by Chinese, Malaysian, and Indian interests. Now, however, French oil-giant Total SA is expected to begin drilling in South Sudan’s Block B in October after a 25 year absence (Business Daily [Nairobi], June 26). Total paid $1.5 million per year to retain its license until operations could be resumed (Dow Jones, October 3, 2006). One of Total’s partners in the original 1980 consortium, Houston-based Marathon Oil, was forced to divest a 32.5% stake in the project earlier this year because of American sanctions. Total has already used its annual report to brace shareholders against a possible drop in share value if U.S. investment funds are forced to divest their Total holdings as a result of the sanctions. Total’s operations will be centered around Bor, capital of Jonglei Province, some 600 miles south of Khartoum. According to a Total official, “Our presence should clearly benefit the peoples of southern Sudan who have exited a long war, by helping with peace building, development, human rights, and democracy” (AFP, July 3).

Crisis in Abyei

Much of Sudan’s oil industry is concentrated in the Abyei district, located in the volatile border region between North and South Sudan. Abyei is the traditional home of the Ngok Dinka, a Nilotic group closely related to the Dinka tribes that form the power base for the SPLA/M. It is also, however, a traditional grazing land for the semi-nomadic Messiriya tribe, Baggara (cattle-owning) Arabs who identify with their Arab kinsmen in North Sudan. Under the CPA, the Messiriya retain their grazing rights in Abyei until the region’s status is decided in 2011. In 1905 the Anglo-Egyptian government of Sudan incorporated the territory of nine Ngok Dinka chiefs into Kordofan province, regarded as part of the North Sudan. After independence in 1956, relations between the Ngok Dinka and the Messiriya deteriorated as the tribes lined up with the southern Anyanya rebels and the Khartoum government, respectively, during the 1956-1972 Civil War. When hostilities resumed in 1983, many Ngok Dinka joined the newly-formed SPLA/M, while the Messirya were urged to join the Murahaleen, horse-borne Baggara militias given free rein to raid and loot Southern tribes in the borderlands between north and south Sudan. The Murahaleen became the model for the Janjaweed of Darfur.

Though the CPA established the Abyei Borders Commission as an independent agency responsible for setting the modern borders of Abyei district, their work has been rejected by Khartoum, which insists on maintaining the 1905 borders that would keep most of Abyei’s oil production in northern hands. The CPA calls for a referendum in the district in 2011 that will determine whether the district joins the South Sudan (which will also vote on separation the same year) or remains an administrative district of the North.

Khartoum has been slow to remove its troops, arguing that they are needed to protect oil facilities. Fighting between the Messiriya and the SPLA has been common in the last two years. As insecurity increased the SAF returned to Abyei earlier this year, where they eventually clashed with the SPLA in intense fighting that flattened the town of Abyei in May and threatened to reopen the civil war. At least 30,000 people were displaced by the fighting. Eventually a June 8 “roadmap” was negotiated, calling for the creation of SAF/SPLA “joint integrated units” to restore order in the region (AFP, July 9). UN forces in the region provided transportation and ten days of training (Sudan Tribune, July 5). This did not prevent the SPLA from accusing the SAF of raiding a village six miles north of Abyei in July, a charge the SAF denied (Reuters, July 23).

The Messiriya have had their own disputes with the oil companies – on May 13 Messiriya tribesmen abducted four Indians working with Petro Energy Contracting Services in south Kordofan. Three escaped in June (though one went missing in the bush), while the fourth was released in late July (AFP, July 25).

United Nations forces are present in the region, tasked primarily with supporting the implementation of the CPA. Formed in 2005 with the agreement of the SPLA and NCP, the United Nations Mission in Sudan (UNMIS) is a Chapter VII peacekeeping force mostly formed from Asian and African troops and is separate from UNAMID, the United Nations African Union Mission in Darfur. UNMIS is deployed in six regions: Bahr al-Ghazal (where Chinese peacekeepers are deployed), Equatoria, Upper White Nile, Nuba Mountains, Southern Blue Nile, and Abyei. UNMIS is not mandated to protect oil facilities.

UN civilian staff evacuated Abyei during the May fighting; several hundred mostly Zambian peacekeepers remained but did not intervene despite being authorized as a Chapter VII force to protect civilians (Sudan Tribune, May 15). After coming under criticism, UNMIS explained that the movement of its Zambian troops had been restricted by the SAF (The Monitor [Kampala], June 16). These restrictions were removed after the June 8 “roadmap” agreement.

Improving SPLA Military Capacity

In June the SPLA introduced a White Paper on Defense in the South Sudanese parliament in Juba despite opposition from the Ministry of National Defense in Khartoum, which claims it is a violation of the CPA (Sudan Tribune, June 27; Al-Ahdath, June 26). The White Paper calls for the creation of regular and reserve land forces, a small navy to patrol rivers, and a new South Sudan Air Force (SSAF). Although the SPLA is experiencing difficulties in paying its existing force, the document calls for the purchase of modern weapons and aircraft, obviously with an eye to use oil revenues for arms purchases necessary to secure the South Sudan’s energy resources.

DynCorp, a U.S.-based private security firm best known for a sex-trade scandal in Bosnia, was given a $40 million contract by Washington in 2006 to provide training and telecommunications to the SPLA. According to a DynCorp official, “The US government has decided that a stable military force will create a stable country” (Sudan Tribune, August 12, 2006). DynCorp lost its contract after numerous irregularities and misconduct by two of its advisors in the field was revealed. The contract was turned over to United States Investigative Services (USIS), another private security firm with close ties to the U.S. administration.

Conclusion

The conflict over Abyei is not a promising sign for peace in the region. If the North-South Civil War resumes, the oil industry will have little choice except to abandon their operations as they did in the 1980s. Khartoum is therefore desperate to find oil in the north (including Darfur) before the 2011 referendum. China is experiencing a moderate risk from JEM in its south Kordofan oil operations, but a move into Darfur will be highly risky, inviting attacks from JEM and other militant groups on their home ground. The Darfur rebels are also determined to claim their share of future oil revenues. The belief that all armed movements will eventually be given a share in these revenues as part of a negotiated settlement has led to increasing factionalism amongst the rebels, in turn increasing insecurity and decreasing the possibility of a negotiated peace.

This article first appeared in the August 11, 2008 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor