Andrew McGregor

Eurasia Daily Monitor 21(146)

Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC, October 9, 2024

Executive Summary:

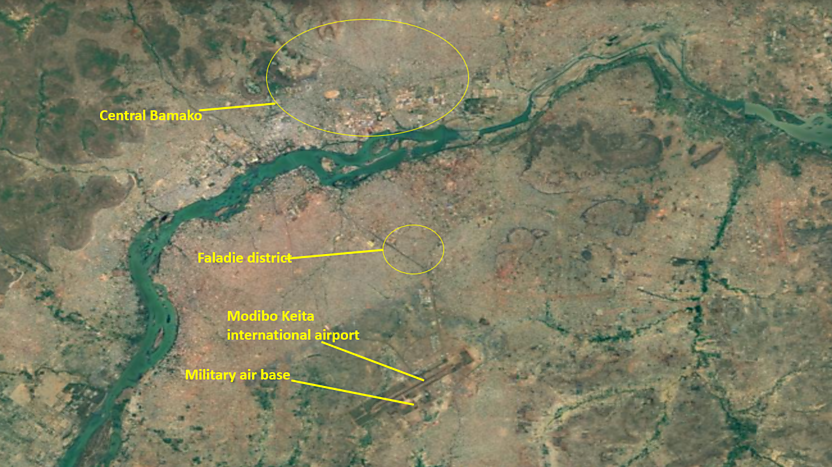

- Over the past months, Russia’s “Africa Corps,” partly made up of former Wagnerites, has faced numerous blows from jihadist groups in Africa’s Sahel states.

- These defeats have begun to raise questions about the future of Russian military forces in the region following the eviction of French and US forces, replaced by Russian mercenaries whose massacres fuel rebel anger and desire for revenge.

- Having seized power unlawfully on the pretext of needing to evict the Western military presence, Sahelian coup leaders’ credibility rests on Russian-backed military success against the jihadists and separatists who challenge them.

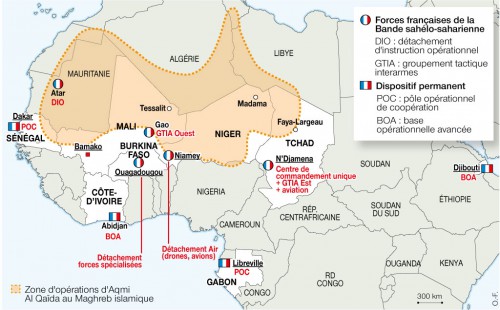

Al-Qaeda has come hunting for Russian troops in the Sahel, scoring another blow against Moscow’s “Africa Corps” in the Malian capital of Bamako on September 17. The attack on Russian and Malian military facilities came a month after a devastating joint strike by al-Qaeda and Tuareg separatists on a Russian/Malian column at Tinzwatène, near the Algerian border. Recent defeats of Russian-backed government forces in Niger, the sudden departure of recently-arrived Russian paramilitaries for urgent deployment on the Kursk Front and the instability of military regimes in three Sahel states belonging to the pro-Russian Alliance des États du Sahel group (AES -Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso) are beginning to raise questions about the future of Russian forces in the region.

Attacker Sets Fire to an Aircraft (Jeune Afrique)

Attacker Sets Fire to an Aircraft (Jeune Afrique)

The attack was carried out by militants of Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wa’l-Muslimin (JNIM), led by a veteran Malian Tuareg jihadist, Iyad ag Ghali. JNIM was formed in 2017 as a coalition of smaller jihadist groups drawn from the Tuareg, Arab and Fulani communities. They pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda almost immediately, and were accepted into the movement. This by no means indicates a general support for al-Qaeda amongst these minority ethnic groups, who are targeted daily in Malian and Russian counterinsurgency operations.

Location of Bamako Attacks (BBCM)

Location of Bamako Attacks (BBCM)

A small number of members of the mostly Fulani Katiba Macina (katiba = battalion) struck two military installations south of the Niger River in the morning of September 17. The leader of the attack on the first target, Senou Air Base 101, a launch point for drone operations against militants in northern Mali, was ‘Abd al-Salam al-Fulani (Chirpwire, September 17, 2024, via BBCM).

The second attack on a gendarmerie school in nearby Faladié was led by Salman “Abu Hudhaifa” al-Bambari, a member of the Muslim Bambara ethnic group. As the dominant ethnic group in the Malian military and government, the Bambara have more often been the target of the jihadists than their allies. The school also serves as a dormitory for Russian troops, who came under attack. Fulani preacher Amadou Koufa, leader of the Katiba Macina, said the operation was in response to massacres of civilians committed by government troops and their Russian allies (al-Zallaqa, September 20, via BBCM).

On the day of the attacks, JNIM issued an inflated claim of heavy losses of “hundreds of Wagner” personnel (Chirpwire, September 17, via BBCM). A more accurate figure is 77 dead and 200 wounded, Malians and Russians combined. Although the GRU (Russian military intelligence) has assumed command of the former Wagner fighters in Africa, former Wagner personnel (who still form about half of the force) are still allowed to wear Wagner insignia, leading many Sahelians to still refer to Russians as “Wagner” (Reuters, September 11). A short video released the day of the Bamako attack purports to show Russian mercenaries who had just killed several militants near the airport (X, September 17). Russian embassy officials deplored the loss of Malian troops, but said nothing about Russian losses (X, September 20).

Young Fulani Men Were Rounded Up in Bamako After the Attack as Suspects: None Wear the Camo-pattern Uniforms Worn by the Attackers (ORTM)

Young Fulani Men Were Rounded Up in Bamako After the Attack as Suspects: None Wear the Camo-pattern Uniforms Worn by the Attackers (ORTM)

A week after the attack on Bamako, Tuareg separatists of the same group that worked with JNIM in the deadly Tinzwatène ambush (the Cadre stratégique pour la défense du peuple de l’Azawad – CSP-DPA), destroyed a Russian command post in Mali’s northern Timbuktu region with a bomb-carrying drone (X APMA, September 25; X Wamaps, September 26).

Fellow AES state Burkina Faso is far from stable, even with Russian support. Captain Ibrahim Traoré’s military regime has survived four coup attempts since it took power in September 2022 and began to evict French and American forces in favor of Russian mercenaries. In the worst terrorist attack in Burkina Faso’s history, JNIM militants killed as many as 400 people at Barsalogho on August 24, including government troops, militia members and civilians (Bamada.net [Bamako], September 17).

A week later, 100 Russian troops of the “Bear Brigade” were withdrawn from Burkina Faso to fight on the Kursk front in Russia after a short three-month deployment. The unit (officially the 81st Bear Special Forces Volunteer Brigade) is a Russian PMC composed of special forces veterans supplied with arms and equipment by the Russian Defense Ministry (L’Indépendent/AFP, August 31). Its members have signed contracts with the GRU (AFP, August 30).

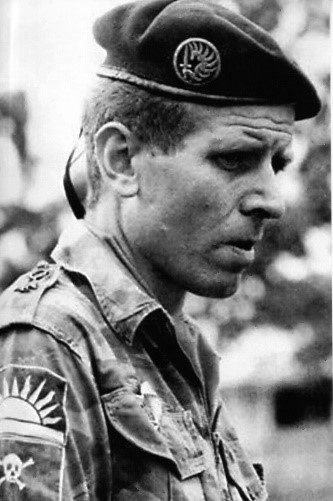

Captain Ibrahim Traoré with Bear Brigade Commander Viktor Yermolaev (Le Monde)

Captain Ibrahim Traoré with Bear Brigade Commander Viktor Yermolaev (Le Monde)

Led by commander Viktor Yermolaev (a.k.a. “Jedi”), one hundred members of the brigade arrived in Burkina Faso in late May to provide security for junta leader Captain Ibrahim Traoré; they were later joined by up to 200 more members. In what might be interpreted as unsettling news for AES junta leaders dependent on Russian military support, Yermolaev announced that “When the enemy arrives on our territory, all Russian soldiers forget about internal problems and unite against a common enemy” (Le Monde, August 29). However, he did promise that his Russian troops would return once their mission in Russia was complete (RFI, August 29).

Niger, the third AES member, is also facing an upsurge in attacks by religious extremists since replacing French and American forces with GRU “mercenaries.” Two days before the strike on Bamako, JNIM’s Katiba Hanifa raided a military post in Niakatire, Niger, killing at least 27 members of a special forces battalion (Chirpwire, September 20, via BBCM; Wamaps, September 15). Katiba Hanifa is a branch of the JNIM/al-Qaeda network led by Abu Hanifa, (A.K.A. Oumarou), a Malian Fulani.

Russia’s strong-handed tactics have not restored order to the post-coup Sahel nations; on the contrary, civilian and military deaths have sky-rocketed. Civilian fatalities are reported to have risen by 65% over the previous year, with both sides bearing responsibility (Reuters, September 11). Nearly half the territory of Sahel Alliance nations is now under rebel or separatist control. Rebel anger and desire for revenge is fuelled by Russian massacres large and small. The Sahelian coup leaders cannot acknowledge the reality of a Russian failure; having seized power unlawfully on the pretext of needing to evict the Western military presence, their credibility rests on Russian-backed military success against the jihadists and separatists who challenge them.