Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report

June 2, 2025

During an April meeting with Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni, President Donald Trump made a reference to the Congo, quickly adding “I don’t know what that is…” (Africa News, April 21). Trump’s senior advisor for Africa, Massad Boulos (whose son is married to Trump’s daughter, Tiffany), quickly reassured Africans that, despite his unfamiliarity with Africa’s second-largest country and its 110 million people, Trump “highly values Africa and African people… Africa is very important to Trump” (BBC, April 23).

Three weeks earlier, Boulos had provided the news that the United States was engaged in talks related to a security-for-critical minerals agreement with Congolese president Felix Tshisekedi (similar to that proposed to Ukraine), adding that “I am pleased to announce that the president and I have agreed on a path forward for its development.” According to Tshisekedi, American might would help keep armed factions like the Congo’s powerful rebel M23 movement “at bay” (AP, April 3). The M23 is widely believed to receive substantial military support from neighboring Rwanda.

It is difficult to say how this military security might be provided. The Congolese government envisions US forces replacing the massive but ineffective UN contingent in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), but any deployment of American troops under the current administration seems unlikely. General Michael Langley, commander of U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM), told a gathering of African military leaders on May 29: “You can no longer depend on the military strength or the financial support of the United States” (Garowe Online, May 31). Washington is considering folding AFRICOM into US European Command, another step in abandoning the resource-rich continent to Russia (Reuters, May 27).

Further complicating matters is the endemic corruption and expectation of bribes that runs unchecked through Congolese society and all its business and government institutions. China has managed to navigate this system with some success in the Congo’s mineral sector through government investment and subsidies to become the DRC’s main mineral partner. Beijing is also expanding its military cooperation with African nations as America’s military steps back (Business Insider Africa, May 31).

The US administration is currently sponsoring peace negotiations between M23 and the government in Kinshasa. With both sides in the conflict having submitted draft peace agreements, US mining firms are reported to have expressed interest in operating in the Congo (The Africa Report, May 28).

The Battle for Tantalum

Tantalum is an especially rare critical mineral, yet its unique properties make it vital in the electronics industry and the manufacture of computer chips and medical implants. Everything from fighter jets to nuclear reactors to smart phones rely on tantalum, with new uses and demand growing daily (Institut für seltene erden und metalle AG [Lucerne], August 2024). The DRC is the world’s largest producer of tantalum, most of it coming from the northeastern provinces of Nord and Sud Kivu, war plagued regions rich in copper, tin, tungsten, gold, cobalt, lithium and the coltan from which tantalum is extracted (Mining.com, April 17).

In 2023, the DRC claimed Rwanda, a country with few mineral deposits of its own, was exporting over $1 billion a year in tantalum, tin, tungsten and gold: “It’s all coming from DRC – that’s obvious” (Financial Times, March 21, 2023). Nonetheless, Rwanda claims to be “among the top producers of Tantalum, producing about 9 per cent of the world’s Tantalum used in electronics manufacturing” (The Great Lakes Eye, November 7, 2023). Between them (regardless of actual origin), the DRC and Rwanda account for 58% of world production of tantalum, the price of which has risen 25% since January due to the insecurity in Kivu (Discovery Alert, May 7). The United States obtains all its tantalum from foreign sources, its own reserves of coltan being of poor quality.

The Warlord of Kivu: Sultani Makenga

“In brief, my life is war, my education is war, and my language is war” (New African, February 15, 2013). In this way, Congolese “General” Sultani Makenga defines his life and purpose as part of an endless cycle of conflict and brutality centered on the Congolese province of Nord Kivu. As the military leader of M23, Makenga currently dominates the eastern Congo and its production of critical minerals.

Like many of his contemporaries, Makenga is the product of the 1994 Rwandan genocide of Tutsis by their Hutu neighbors that eventually spilled over into the neighboring Nord and Sud Kivu provinces of the eastern DRC. Sharing borders with Uganda and Rwanda, the Kivu region is rich in minerals and other resources, but residents cope with poverty and violence as the region has become a relentless battleground for local Tutsis, exiled Hutu génocidaires, Islamist extremists, bandit groups, a deeply corrupt Congolese army and regulars of the Ugandan and Rwandan militaries.

Under Makenga’s direction, Nord Kivu’s M23 movement has been accused of committing numerous atrocities and human rights violations, including massacres of civilians, mass rapes and the recruitment of child soldiers (US Treasury Department, November 13, 2012). Makenga is unapologetic for his role in the violence that plagues the Kivu region:

I am a soldier, and the language that I know is that of the gun. My home has been in the bush, fighting injustice and corrupt regimes in this region. Therefore, when a politician wants to play politics with me, my response won’t be the political podium but the barrel of the gun because that’s my way of fighting for my rights (New African, February 15, 2013).

Makenga’s Early Life

Makenga enjoys a reputation as one of the finest strategists and tacticians in east-central Africa (ChimpReports, February 6, 2017). Always well-guarded, Makenga avoids making speeches or public appearances, and walks with a cane after being wounded in Katanga during a rebellion there in the late 1990s (Le Monde, April 7, 2023).

This Tutsi warlord was born in the Nord Kivu town of Masisi in 1973 with the full name of Nziramakenga Ruzandiza Emmanuel Sultan, but grew up in the nearby town of Rutshuru. Makenga is a member of the Mugogwe sub-group of the Tutsi (New African, February 15, 2013). Like Makenga, many members of the M23 group are Congolese Tutsis closely related to the Tutsi population in neighboring Rwanda. Many of the Congo’s Tutsis descend from Rwandan migrant workers encouraged by Belgian colonialists to settle in Nord Kivu in the 1930s; as a result, accusations of being “foreigners” frequently surface during regional episodes of ethnic tension. Part of the M23’s effort to establish local control in these communities includes the destruction of records delineating the lineage of traditional authority in Nord Kivu (The Conversation, October 24, 2024).

The Rwandan Civil War

After dropping out of school, Makenga moved to Uganda, where he underwent six months of military training. He then joined the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) in 1990 at age 17 with the intention of fighting the anti-Tutsi regime of President Juvénal Habyarimana in Rwanda before the president’s assassination in 1994 (New African, February 15, 2013). The RPF was a movement of Tutsi exiles determined to end Hutu domination of Rwanda and restore “traditional” Tutsi rule.

Despite the minimal education common to herding boys like Makenga and a difficulty in speaking French or English (though he is fluent in Swahili and Kinyarwanda), the young Makenga rose to the rank of sergeant by the end of the conflict, one of the highest ranks available to Congolese Tutsis in the RPF (Le Monde, April 7, 2023; Riftvalley.net, 2018). He became known for his tactical skills, especially in setting ambushes (Riftvalley.net, 2018).

Roughly one million Hutus fled Rwanda after the RPF victory left them fearing retribution for the murder of 800,000 Tutsis and politically moderate Hutus. After their arrival in Nord Kivu, the Hutu destabilized the whole region by forming extremist militias (Interhamwe) that mounted cross-border raids and attacked local Congolese Tutsis. Little help could be obtained from the corrupt and incompetent army of dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, the Forces Armées Zaïroises (FAZ – the Congo was renamed Zaïre from 1981 to 1997). Their failure to provide security would eventually lead to a national rebellion supported by Rwanda and Uganda that would depose Mobutu.

When the Tutsi-Hutu struggle in Rwanda ended in 1996, Makenga decided to return home to the DRC and “fight for my country.” It was then that he met Laurent-Désiré Kabila and together, in Makenga’s words, “launched the liberation struggle for the Congo” (New African, February 15, 2013).

Makenga and the First Congo War – 1996-1997

Kabila’s chief strategist, the Rwandan James Kabarebe, led the rebel Alliance des Forces Démocratiques pour la Libération du Congo-Zaïre (AFDL), a coalition that captured Kinshasa, overthrew Mobutu and seized power on May 17, 1997. Burundi and Angola joined Uganda and Rwanda in supporting the broad-based military operation. Zaïre was renamed the “Democratic Republic of the Congo” (DRC) and Laurent-Désiré Kabila installed as the DRC’s new president.

Makenga broke with Kabila in 1997, accusing him of continuing the marginalization of the Congolese Tutsis. A refusal to obey AFDL orders left Makenga to serve a term on the Rwandan prison island of Iwawa in Lake Kivu (Le Monde, April 7, 2023).

The Congolese Tutsis who played a prominent part in the overthrow of Mobutu were later branded as “foreigners” by now-President Kabila, who insisted they “return” to Rwanda (New African, February 15, 2013). His declaration repeated Mobutu’s own November 1996 order for Congolese Tutsis to leave the country. As Makenga reflected: “You help someone to become president through the gun, but when he tastes power, you become his first victim” (New African, February 15, 2013).

Makenga and the Second Congo War – 1998-2003

Now opposed to the rule of Kabila, who had expelled his Rwandan supporters and persecuted the Congolese Tutsis, Makenga joined Uganda’s elite Nguruma Battalion. The unit took part in an audacious operation planned by Rwanda’s James Kabarebe, former chief-of-staff of Kabila’s armed forces before his dismissal in July 1998. The Kitona Airlift of August 1998 began with the capture of the airport at Goma (provincial capital of Nord Kivu) and the hijacking of four civilian passenger planes, which over two days ferried some 3,000 Rwandan and Ugandan troops 1200 miles to the DRC’s far west, where they seized the Atlantic port of Matadi and the Inga Dam, cutting off power to the capital of Kinshasa. The bold plan only failed due to the intervention of Zimbabwean, Namibian and Angolan troops. Both the operation and its repression were marked by widespread rape, murder and looting on all sides. Back in Nord Kivu, Rwandan forces attacked camps believed to host the Hutu militia known as the Forces démocratiques de libération du Rwanda (FDLR).

After nearly three years of war, Joseph Kabila succeeded his father Laurent as president after the latter’s assassination by one of his cousins on January 16, 2001. Joseph Kabila would remain president until 2019, when he was succeeded by current president Félix Tshisekedi after a series of bloody mass protests against his rule.

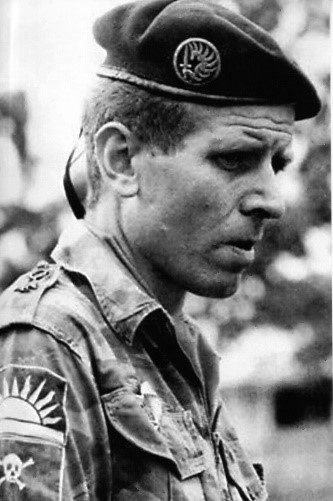

Joseph Kabila (The Africa Report)

Joseph Kabila (The Africa Report)

Makenga became a major in the Rwandan-backed Tutsi rebel movement Rassemblement congolais pour la démocratie (RCD) in 1998. Many members were veterans of the AFDL. The movement succeeded in taking Goma in August 1998, but by 1999-2000, the group had splintered, diminishing its importance before a regional agreement brought an end to the Second Congo War in 2003.

Makenga and the New War of the CNDP

Backed by Uganda and Rwanda, the anti-Kabila General Laurent “The Chairman” Nkunda formed the Nord Kivu-based Congrès national pour la défense du people (CNDP) in December 2006. Kabila had fallen out of favor with his former backers, including Makenga, who joined many AFDL/RCD veterans in the new movement.

An October 2008 CNDP offensive brought the group to the outskirts of Goma after the Congolese garrison had looted the city and fled. Instead of occupying the city, Nkunda declared a unilateral ceasefire, creating dissension among CNDP fighters (al-Jazeera, October 30, 2008; UNSC November 2008 Monthly Forecast, October 30, 2008).

CNDP fighters under Makenga’s command were accused of participating in the November 4-5 2008 massacre of 67 civilians in the Nord-Kivu town of Kiwanja despite the nearby presence of UN peacekeepers who failed to intervene (Independent Online [Johannesburg], June 19, 2012).

After a violent split in the movement, Nkunda was arrested by Rwandan authorities in January 2009. General Bosco “The Terminator” Ntaganda (a Rwandan Tutsi) took over one faction of the movement, which quickly began cooperating with the Congo’s new national army, the Forces Armées de la République Démocratique du Congo (FARDC), against Hutu rebel movements (For Ntaganda, see Militant Leadership Monitor, August 31, 2012). FARDC is known for its indiscipline, poor morale and habitual shortages of food, ammunition and salaries.

Both CNDP factions were given refuge by Rwanda and Uganda, which ignored DRC extradition requests for Makenga and others (Africa Confidential, July 7, 2022). The CNDP agreed to a peace accord brokered in Nairobi on March 23, 2009 that saw many of its fighters integrated into the FARDC. Makenga was made a colonel in FARDC and served in Sud Kivu (Riftvalley.net, 2018; Le Monde, April 7, 2023).

The M23

On April 4, 2012, Ntaganda and 300 loyalists deserted the DRC but took losses in a clash with FARDC in the Rutshuru district (ChimpReports, February 6, 2017). Makenga, then second-in-command of DRC operations against the Hutu FDLR, followed Ntaganda by deserting in May. With his experience, he was made a general in the new M23 movement and took military command of the rebel force. Joseph Kabila suspended joint operations with Rwanda when the number of desertions to M23 became critical.

The new formation’s name, M23, derived from its demand for the full implementation of the March 23, 2009 accord between the DRC and the CNDP, which the DRC government was backing away from. Fuelling the new insurgency was the government’s failure to stabilize the eastern Congo and its inability to provide services to local people.

In November 2012, Makenga attracted international attention when UN defenders fled Goma and his forces briefly captured the city, the capital of Nord Kivu. It was apparently a step too far for his backers; visits from Rwandan Army chief Lieutenant General Charles Kayonga and top Ugandan officers encouraged Makenga to withdraw (ChimpReports, February 6, 2017).

Makenga claims to have taken advantage of FARDC’s corruption to equip his force: “When the Kinshasa government buys new weapons, I also get a share of it through my own contacts within the Congolese national army” (New African, February 15, 2013).

Makenga was sanctioned by the US in November 2012 for “contributing to the conflict in the DRC” (US Treasury Department, November 13, 2012). Specifically, Makenga was cited for committing or being responsible for murder, rape of children as young as eight, kidnapping and forcible recruitment of children in Makenga’s Rutshuru home territory (UNSC, October 29, 20; BBC Africa, November 7, 2013; New African, February 15, 2013). According to Navi Pillay, then U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights: “The leaders of the M23 figure among the worst perpetrators of human rights violations in the Democratic Republic of Congo, or in the world for that matter” (UN News, June 19, 2012).

M23 Defeat and Split – 2013

Factionalism disrupted M23 operations, preventing the group from exploiting its successes in Nord Kivu. Makenga was deeply involved in the splits, first coming to blows with a faction led by Bishop Jean-Marie Runiga Lugerero. In February 2013, Bishop Runiga, other M23 leaders and several hundred fighters were given refuge in Rwanda after intense fighting with the Makenga faction (East African, July 13, 2013).

Makenga’s forces also clashed with those of Bosco Ntaganda in March 2013 after Makenga learned Ntaganda was planning to have him killed. Ntaganda’s attack on Makenga’s base was repulsed with heavy casualties, forcing Ntaganda and 200 men to also take refuge in Rwanda. Ntaganda turned himself in to the US Embassy in Kigali and was extradited to face an ICC proceeding in the Hague (Al-Jazeera, November 5, 2013; ChimpReports, February 6, 2017).

The Terminator on Trial: Bosco Ntaganda at the ICC

The Terminator on Trial: Bosco Ntaganda at the ICC

In November 2013 it was Makenga’s turn to flee Nord Kivu after defeat at the hands of FARDC and the UN’s Force Intervention Brigade. Rather than Rwanda, Makenga and other members of M23 crossed into Uganda, where they surrendered to authorities. The collapse of M23 through infighting and external military pressure led to the Kampala-brokered Declarations of Nairobi ceasefire agreement signed on December 12, 2013 by the DRC Government and the M23 movement.

Reviving the M23

In November 2016 Makenga left a demobilization camp in Uganda, crossed into Nord Kivu and began recruiting from Tutsi refugee camps in an effort to revive the M23 (ChimpReports [Kampala], November 13, 2016). He was joined there by former CNDP fighters who left their cantonment in Uganda.

Beginning with a small group of 400 men, Makenga eventually relaunched the M23 rebellion in November 2021. A new offensive took large parts of Nord Kivu before a ceasefire in November 2022. Makenga, however, accused the DRC authorities of insincerity: “If they desire peace, we will achieve it together. If they choose war, we will fight. That is our stance” (Igihe [Kigali], July 7, 2023).

Retaking Nord Kivu – 2024-2025

A July 2024 report by the UNSC Group of Experts presented evidence that the UPDF and Ugandan military intelligence were actively supporting Makenga and other M23 leaders. It also claimed there were 3,000 to 4,000 Rwandans fighting alongside M23, putting Rwanda in “de facto control” of M23 operations (UNSC, June 4). Uganda rejected the claims, while Kigali insisted that the DRC was financing and fighting alongside the FDLR; Rwanda was thus only acting in self-defense (AFP, July 10, 2024; al-Jazeera, July 9, 2024).

DRC Wazalendo Militia near Rutshuru, 2022 (Moses Sawasawa/AP)

DRC Wazalendo Militia near Rutshuru, 2022 (Moses Sawasawa/AP)

Besides FARDC and the FDLR, Makenga’s M23 are also confronted by the Wazalendo (Kiswahili – “patriots), local militias traditionally known as Mayi-Mayi and nominally aligned with the DRC government. Among these are Guidon Shimiray Mwissa’s Nduma defense du Congo – Renové (NDC-R), Janvier Karairi’s Alliance des patriotes pour un Congo libre et souverain (APCLS) and the mostly Hutu Collectif des Mouvements pour le Changement-Forces de Défense du Peuple’ (CMC-FDP). All these loosely-organized, drug-fuelled Mayi-Mayi groups are feared by local communities and are known for brutality, extortion and mass rape. [1]

Makenga was sentenced to death in absentia, by a Congolese military court on August 8, 2024. The M23’s military leader was one of 26 armed-group leaders condemned after a trial, including Corneille Nangaa, political leader of the rebel Congo River Alliance (which includes M23), and M23 political chief Bertrand Bisimwa (al-Jazeera, August 9). The death penalty in the DRC had been under a moratorium since 2003, but was restored in March 2024.

As the M23 closed in on Goma in 2024, a FARDC spokesman claimed the M23 had blocked legitimate trade routes through Goma to focus on smuggling tanatalum supplies into Rwanda, a claim denied by Rwandan authorities (Bloomberg News, March 15, 2024).

Makenga launched a final offensive on Goma on January 23, in which his forces, allegedly supported by Rwandan troops, quickly broke through defenders that included FARDC troops, FDLR fighters, Wazalendo gunmen, peacekeepers from the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and Romanian mercenaries (for the latter, see MLM, June 27, 2024). By January 30, the conquest of Goma was complete; at the same time other M23 units were seizing a number of sites in Sud Kivu producing tantalum, tin and gold.

Goma lies in the shadow of the active volcano Mount Nyiragongo

Goma lies in the shadow of the active volcano Mount Nyiragongo

Goma Again

Some 2900 people were slaughtered in the M23 conquest of Goma, which was accompanied by the escape of hundreds of prisoners from Goma’s Munzenze prison; over 100 female prisoners were immediately raped and then left to burn alive when the escapees set fire to the facility (BBC, February 5). Bizarrely, photos of the murdered women being carried out in body bags surfaced during Donald Trump’s May 21 Oval Office meeting with South African president Cyril Ramaphosa, when they were produced by Trump as visual proof of a “white genocide” in South Africa (Reuters, May 22; IBTimes, May 28). M23 forces then entered Bukavu, capital of Sud Kivu, on February 16, taking full control of the city two days later (Al-Jazeera, February 16).

Residents greet a vehicle with M23 fighters on it in Bukavu, 2025 (Amani Alimasi/AFP)

Residents greet a vehicle with M23 fighters on it in Bukavu, 2025 (Amani Alimasi/AFP)

The Hutu Mayi Mayi CMC-FDP attacked Goma on April 11 in an attempt to drive out the M23, but were repulsed. M23 spokesmen claimed South African peacekeepers supported the assault (Congovirtuel, April 13; RFI, April 13). Violent crime has plagued the city since the January conquest with M23 fighters struggling to maintain order.

Ex-president Joseph Kabila, accused since February by President Tshisekedi of being behind the M23 offensive, and apparently back in favor with Makenga and Corneille Nangaa, returned to Goma on May 25 from a self-imposed exile in South Africa and Rwanda that began in 2023. Nangaa announced Kabila was welcome “in the only part of the country where arbitrariness, political persecution, death sentences, tribalism, discrimination, hate speech… do not exist” (New Times [Kigali], May 26).

The DRC government believes Kabila is now positioning himself to assume leadership of the rebel forces (Reuters, May 28). Kabila’s return is certain to complicate the US-sponsored negotiations between the competing factions in the DRC and the mineral deal desired by the Trump administration (Kivu Morning Post, May 27; Reuters, May 28). Just as Joseph Kabila’s father, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, had once labelled Congolese Tutsis as “foreigners,” the leader of President Tshisekedi’s Union for Democracy and Social Progress (UDPS) declared on May 25 that Joseph Kabila was “not Congolese… Let him leave the Congolese to deal with their own problems. He, a Rwandan subject whose rule was imposed on us, must leave the Congolese alone” (France 24, May 29).

Conclusion

While American military intervention to secure critical mineral supplies in the Congo appears unlikely at present, Trump supporter and mercenary chief Erik Prince has been engaged in working out an agreement with Congo’s finance ministry that would see private military contractors assigned to tax collection duties in the mineral sector and anti-smuggling operations (Reuters, April 17, 2025). There are reports that a recruiter allegedly working for Prince has been approaching former French Legionnaires regarding military contract work in the Congo (Africa Intelligence, May 12).

Rwandan media has accused Belgium of deploying two companies of commandos to fight against M23 alongside FARDC, FDLR and Wazalendo (Great Lakes Eye, March 24; Great Lakes Eye, May 7). Eight Belgian soldiers, including a “Sergeant Jimmy Luis Flander,” are said to have been killed while operating in Nord Kivu (Great Lakes Eye, April 3). This may be part of an effort to divert attention from international accusations that Kigali is supporting M23; Belgian Foreign minister Maxime Prévot described the assertions as “grotesque fake news” and disinformation designed to “undermine Belgium’s image, to increase tensions and to legitimise a certain interventionism” (Belga News Agency, March 26).

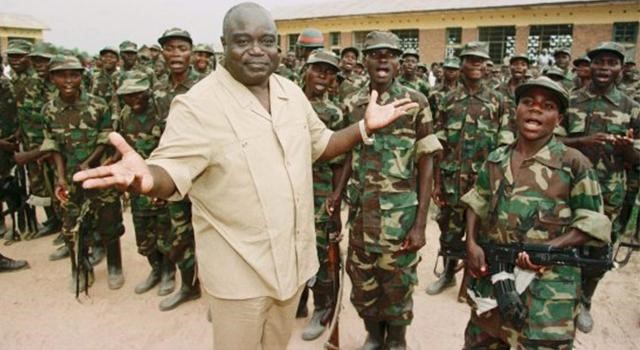

Sultani Makenga (Chrispin Mvano)

Sultani Makenga (Chrispin Mvano)

Sultani Makenga’s career as a warlord, endlessly shifting from one faction to another in a process of continual self-enrichment, is emblematic of the interminable nature of the conflict in the Congo. The ceaseless struggle to control its abundant and strategically important wealth invites a steady stream of foreign interests willing to partner with corrupt businessmen, power hungry politicians and uniformed war criminals. Where the search for oil and gas reserves fueled international conflicts in the recent past, new elements are now sought after to achieve global dominance in a technological age. The struggle to possess these mineral properties, antagonized by post-colonial ethnic conflicts, has brought only death and displacement to millions of residents of Nord Kivu, with no end in sight. Men like Sultani Makenga, indulged and supported by parties (Western, African and Eastern) that wish to keep their hands clean of the blood of impoverished Africans, are ultimately the agents, not causes, of the resource-driven disease that ravages the Congo.

Note

- Mercenary leader Major Mike Hoare, who led his 5 Commando in the Kivu region in the 1960s, attributed the foundation of the Mayi Mayi movement to Chinese-trained revolutionary Pierre Mulele (1929-1968), who encouraged his Simba followers to chant “Mayi Mayi” (water water) or “Mayi Mulele” as they entered battle. The chant was intended to combine with magical water dispensed to the fighters to render them immune to bullets: “This, together with liberal doses of marijuana, rendered the recipient insensible to pain and totally incapable of intelligent action” (Hoare, Congo Mercenary, London, 1967). The practice was, in fact, an adaptation of earlier rituals used in Central Africa to overcome the superior firepower of colonial forces.