Andrew McGregor

December 15, 2016

In October 2011, Field Marshal Muhammad Hussein Tantawi declared “the military situation in Sinai is 100 percent secure” (Daily News Egypt, October 6, 2011). Four years later, Army spokesman Brigadier General Muhammad Samir assured Egyptians that the North Sinai was “100 percent under control” (al-Jazeera, July 2, 2015). Even Dr. Najih Ibrahim, a former jihadist and principal theorist of Egypt’s al-Gama’a al-Islamiya (GI – Islamic Group) declared as recently as last August that for Sinai’s branch of the Islamic State: “This is the beginning of the end for this organization… It cannot undertake big operations, such as the bombing of government buildings, like the bombing of the military intelligence building previously … or massacre, or conduct operations outside Sinai. Instead, it has resorted to car bombs or suicide bombings, which are mostly handled well [by Egyptian security forces]” (Ahram Online, August 11; August 15).

Since then, Islamic State militants have carried out highly organized large-scale attacks on checkpoints in al-Arish, killing 12 conscripts on October 12 and another 12 soldiers on November 24. Together with a steady stream of almost daily IED attacks, mortar attacks and assassinations, it is clear that militancy in North Sinai is far from finished.

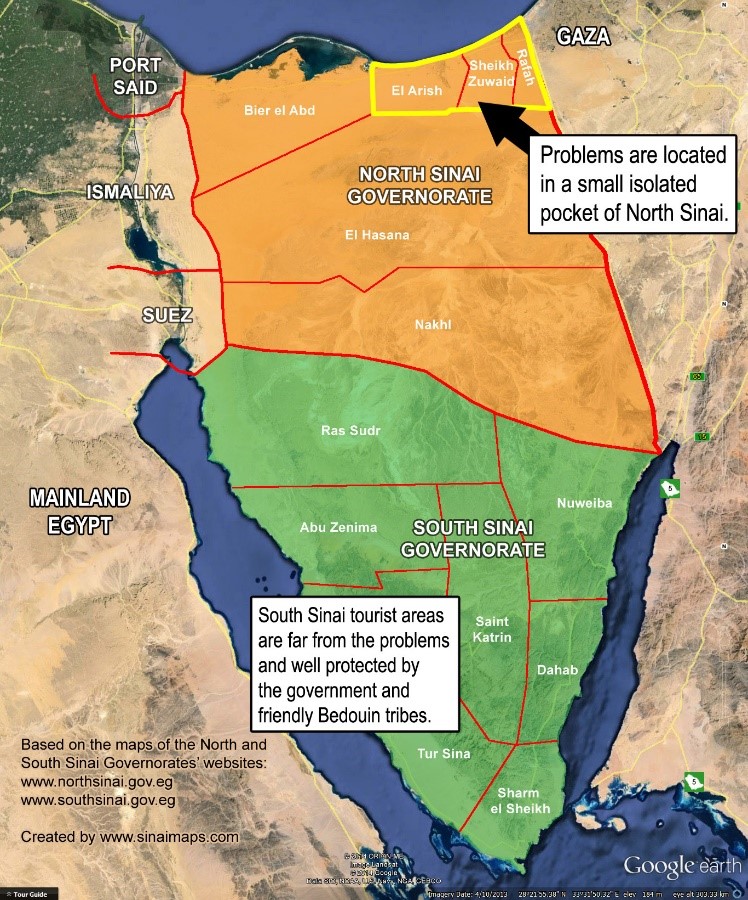

Since 2004 there have been a series of jihadist groups operating in the Sinai. The latest face of militancy in the region is the Wilayet Sayna (WS – “Sinai Province”), a name adopted by the Sinai’s Ansar Beit al-Maqdis (ABM – Supporters of Jerusalem) following its declaration of allegiance to the IS militant group in November 2014. The secretive WS has been estimated to include anywhere from several hundred to two thousand fighters. Despite operating for the most part in a small territory under 400 square miles in with a population of roughly 430,000 people, a series of offensives since 2013 by the Arab world’s most powerful army in North Sinai have produced not victory, but rather a war of attrition. The question therefore is what exceptional circumstances exist in the North Sinai that prevent Egypt’s security forces from ending a small but troubling insurgency that receives little outside support.

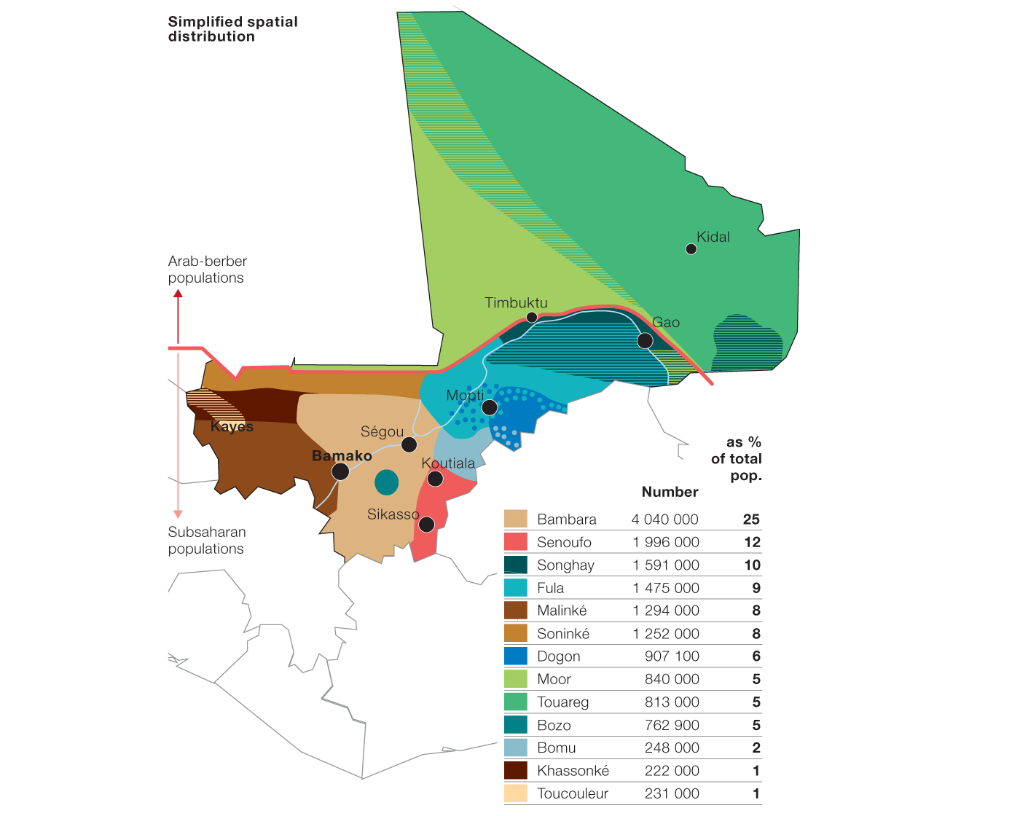

As in northern Mali in 2012, the conflict in Sinai has merged a localized ethnic insurgency with externally-inspired Salafi-Jihadism. The conflict persists despite the wide latitude granted by Israel in terms of violating the 1979 Camp David Accords’ restrictions on arms and troops deployed by Egypt in the Sinai. Unsettled by the cross-border activities of Gazan and Sinai terrorists, Israel has basically granted Cairo a free hand in military deployments there since July 2015.

At the core of the insurgency is Sinai’s Bedouin population, culturally and geographically separate from the Egyptian “mainland.” Traditionally, the Bedouin of the Sinai had closer relations with Gaza and Palestine to the northeast than the Egyptian nation to their west, though Egypt’s interest in the Sinai and its resources dates to the earliest dynasties of Ancient Egypt. The Israeli occupation of the region in 1967-1979 left many Egyptians suspicious of pro-Israeli sympathies amongst the Bedouin (generally without cause) and led to a ban on their recruitment by Egypt’s military or security services.

According to Egyptian MP Tamer al-Shahawy (a former major-general and military intelligence chief), social changes began in the Sinai after the 1973 war with Israel: “After the war a major rift in tribal culture occurred — on one hand was the pull of the Sufi trend, on the other the pull of money from illegal activities such as smuggling, drug trafficking and arms dealing… For a number of reasons the government was forced to prioritize a security over a socio-economic political response.” (Ahram Online, August 15).

Lack of development, land ownership issues and Cairo’s general disinterest in the region for anything other than strategic purposes erupted in the terrorist bombings of Red Sea tourist resorts from 2004 to 2006. The deaths of at least 145 people led to a wave of mass arrests, torture and lengthy detentions that embittered the Bedouin and further defined the differences between “Egyptians” and the inhabitants of the Sinai Peninsula. With the local economy struggling due to neglect and insecurity, many young men turned to smuggling, a traditional occupation in the region. Like northern Mali, however, smuggling has proven a gateway to militancy.

In recent decades, Islamist ideology has been brought to the Sinai by “mainland” teachers and by students returning from studies in the Nile Valley. Inattention from government-approved religious bodies like al-Azhar and the Ministry of Religious Endowments left North Sinai’s mosques open to radical preachers denouncing the region’s traditional Sufi orders. Their calls for an aggressive and Islamic response to what was viewed as Cairo’s “oppression” and the support available from Islamist militants in neighboring Gaza led to a gradual convergence of “Bedouin issues” and Salafi-Jihadism. Support for groups like ABM and WS is far from universal amongst the tribes and armed clashes are frequent, but the widespread distaste for Egypt’s security forces and a campaign of brutal intimidation against those inclined to work with them have prevented Cairo from exploiting local differences in its favor. The army claims it could “instantaneously purge” Sinai of militants but has not done so out of concern for the safety of residents (Ahram Online, March 21).

Egypt’s Military Operations in the Sinai

Beginning with Operation Eagle’s deployment of two brigades of Sa’iqa (“Thunderbolt) Special Forces personnel in August 2011, Cairo has initiated a series of military operations designed to secure North Sinai, eradicate the insurgents in the Rafah, al-Arish and Shaykh al-Zuwayad districts of North Sinai, eliminate cross-border smuggling with Gaza and protect the Suez Canal. While meeting success in the latter two objectives, the use of fighter jets, artillery, armor, attack helicopters and elite troop formations have failed to terminate an insurgency that has intensified rather than diminished.

Al-Sa’iqa (Special Forces) in Rafah

Al-Sa’iqa (Special Forces) in Rafah

The ongoing Operation Martyr’s Right, launched in September 2015, is the largest military operation yet, involving Special Forces units, elements of the second and third field armies and police units with the aim of targeting terrorists and outlaws in central and northern Sinai to “pave the road for creating suitable conditions to start development projects in Sinai.” (Ahram Online, November 5, 2016). Each phase of Martyr’s Right and earlier operations in the region have resulted in government claims of hundreds of dead militants and scores of “hideouts,” houses, cars and motorcycles destroyed, all apparently with little more than temporary effect.

Military-Tribal Relations

Security forces have failed to connect with an alienated local population in North Sinai. Arbitrary mass arrests and imprisonments have degraded the relationship between tribal groups and state security services. Home demolitions, public utility cuts, travel restrictions, indiscriminate shelling, the destruction of farms and forced evacuations for security reasons have only reinforced the perception of the Egyptian Army as an occupying power. Security services are unable to recruit from local Bedouin, while ABM and WS freely recruit military specialists from the Egyptian “mainland.” It was a Sa’aiqa veteran expelled from the army in 2007, Hisham al-Ashmawy, who provided highly useful training in weapons and tactics to ABM after he joined the movement in 2012 (Reuters, October 18, 2015). Others have followed.

The role of local shaykhs as interlocutors with tribal groups has been steeply devalued by the central role now played by state security services in appointing tribal leaders. In 2012, a shaykh of the powerful Sawarka tribe was shot and killed when it became widely believed he was identifying jihadists to state security services (Egypt Independent, June 11, 2012)

The use of collective punishment encourages retaliation, dissuades the local population from cooperation with security forces and diminishes the reputation of moderate tribal leaders who are seen as unable to wield influence with the government. Egypt’s prime minister, Sherif Ismail, has blamed terrorism in North Sinai on the familiar “external and internal forces,” but also noted that under Egypt’s new constitution, the president could not use counter-terrorism measures as “an excuse for violating public freedoms” (Ahram Online, May 10).

Operational Weaknesses

The government’s media blackout of the Sinai makes it difficult to verify information or properly evaluate operations. Restrictions on coverage effectively prevent public discussion of the issues behind the insurgency, reducing opportunities for reconciliation. Nonetheless, a number of weaknesses in Cairo’s military approach are apparent:

- Operations are generally reactive rather than proactive

- A military culture exists that discourages initiative in junior officers. This is coupled with an unwillingness in senior staff to admit failure and change tactics compared to the tactical flexibility of insurgents, who are ready to revise their procedures whenever necessary

- An over-reliance on airpower to provide high fatality rates readily reported in the state-owned media to give the impression of battlefield success. The suppression of media reporting on military operations in Sinai turns Egyptians to the militants’ social media to obtain news and information

- The widespread use of poorly-trained conscripts. Most of the active fighting is done by Special Forces units who reportedly inflict serious losses in their actions against WS. As a result, WS focuses on what might be termed “softer” military targets for their own attacks; checkpoints manned by conscripts and conscript transports on local roads. There are reports of poorly paid conscripts leaking information to Sinai-based terrorists for money (Ahram Online, October 21).

- A failure to prevent radicalization by separating detained Sinai smugglers or militants with local motivations from radical jihadists in Egyptian prisons

- An inability to stop arms flows to the region. Though effective naval patrols and the new 5 km buffer zone with Gaza have discouraged arms trafficking from the north, arms continue to reach the insurgents from the Sharqiya, Ismailiya and Beni Suef governorates

Islamist Tactics in Sinai

The Islamist insurgents have several advantages, including intimate knowledge of the local terrain and a demonstrated ability to rejuvenate their numbers and leadership. Possession of small arms is also extremely common in Sinai despite disarmament efforts by the state. The WS armory includes Kornet anti-tank guided missiles, RPGs and mortars. Many weapons have been captured from Egyptian forces operating in the Sinai.

According to WS’ own “Harvest of Military Operations” reports, IEDs are used in about 60% of WS attacks, guerrilla-style attacks account for some 20%, while the remainder is roughly split between sniper attacks and close-quarter assassinations. Since 2013, over 90% of the targets have been military or police personnel as well as suspected informants (al-Jazeera, May 1). In 2016, IED attacks have numbered roughly one per day. The bombs are commonly disguised as rocks or bags of garbage.

Egyptian Army Checkpoint, al-Arish

Egyptian Army Checkpoint, al-Arish

Well-organized assaults on security checkpoints display a sophistication that has worried military leaders. Checkpoint attacks since October 2014 often involve the preliminary use of suicide bomb trucks to smash the way through fixed defenses, followed by assaults by gunmen, often in 4×4 vehicles which have been banned in military operational zones since July 2015. Car bombs and mortars have been used to launch as many as 15 simultaneous attacks, demonstrating advanced skills in operational planning. Snipers are frequently used to keep security forces on edge and the ambush or hijacking of vehicles on the road complicates the movement of security personnel.

Military intelligence has not been able to overcome WS security measures. WS is notoriously difficult to infiltrate – recruits are closely vetted and often assume new identities. Trackable communications devices are discouraged and the group’s cell structure makes it difficult to obtain a broader picture of its organization and membership. At times it is not even clear who the group’s leader is. Sinai Bedouin chiefs have complained that when they do give warnings to the military of militant activity, their warnings are ignored (Egypt Independent, August 7, 2012)

There is intense intimidation of residents not sympathetic to WS and its aims. The group has even warned ambulance drivers not to transport wounded security personnel to hospitals (Shorouk News, December 21, 2015). Suspected informants are shot, though the WS tries to remain on good terms with locals by providing financial aid and social assistance. Sympathetic residents are able to provide a steady flow of intelligence on Egyptian troop movements and patterns.

Brigadier General Hisham Mahmoud (Daily News Egypt)

Brigadier General Hisham Mahmoud (Daily News Egypt)

WS focuses on state institutions as targets and rarely carries out the type of mass-casualty terrorist attacks on civilians common to other theaters of jihad. However, public, security and religious figures are all subject to assassination. In November, WS beheaded a respected 100-year-old Sufi shaykh of the Sawarka tribe for “practicing witchcraft” (Ahram Online, November 21). Even senior officers are targeted; in November Air Force Brigadier General Hisham Mahmoud was killed in al-Arish; a month earlier Brigadier Adel Rajaei (commander of the 9th Armored Division and a veteran of North Sinai) was killed in Cairo. Both men were shot in front of their own homes (Ahram Online, November 4). In July, a Coptic priest in al-Arish was murdered by Islamic State militants for “fighting Islam” (Ahram Online, July 1). Religious sites inconsistent with Salafist beliefs and values are also targeted for destruction. The shrine of Shaykh Zuwayad, who came to Egypt with the conquering Muslim army of ‘Amr ibn al-‘As in 640 C.E., has been attacked multiple times in the city that bears his name.

When Egyptian military pressure becomes too intense, insurgents are able to take refuge in Jabal Halal, a mountainous cave-riddled region south of al-Arish that acts as a main insurgent stronghold and hideout for fugitives. The area is home to many old Israeli minefields that discourage ground operations, though Egypt’s Air Force claims to have killed scores of militants there in airstrikes (Egypt Independent, August 20, 2012).

Conclusion

Egypt’s large scale counter-insurgency operations have been disappointing for Cairo. Such operations do not have the general support of the local population and are regarded by many as suppression by outsiders. The army and police are not regarded as guarantors of security, but as the violent extension of state policies that discriminate against communities in the North Sinai. So long as these conditions remain unchanged, Egypt’s security forces will remain unable to deny safe havens or financial support to militant groups. Air-strikes on settled areas, with their inevitable indiscriminate and collateral damage, are especially unsuited for rallying government support.

Excluding the Bedouin from Interior Ministry forces foregoes immediate benefits in intelligence terms, leaving security forces without detailed knowledge of the terrain, groups, tribes and individuals necessary to successful counter-terrorism and counter-smuggling operations. However, simply opening up recruitment is not enough to guarantee interest from young Bedouin men; in the current environment they would risk ostracization at best or assassination at worst. With few economic options, smuggling (and consequent association with arms dealers and drug traffickers) remains the preferred alternative for many.

Seeking perhaps to tap into the Russian experience in Syria, Egypt conducted a joint counter-insurgency exercise near al-Alamein on the Mediterranean coast in October. The exercise focused on the use of paratroopers against insurgents in a desert setting (Ahram Online, October 12, 2016). Russia is currently pursuing an agreement that would permit Russian use of military bases across Egypt 10 October 2016 (Middle East Eye, October 10; PressTV [Tehran], October 10). If Cairo is determined to pursue a military solution to the Islamist insurgency in Sinai, it may decide more material military assistance and guidance from Russia will be part of the price.

A greater commitment to development is commonly cited as a long-term solution to Bedouin unrest, though its impact would be smaller on ideologically and religiously motivated groups such as WS. Development efforts are under way; last year President Abd al-Fattah al-Sisi committed £E10 billion (US$ 560 million) to new industrial, agricultural, transport and housing projects (al-Masry al-Youm, March 8). Unfortunately, many of these projects are in the Canal Zone region and will have little impact on the economy of North Sinai. More will be needed, but with Egypt currently experiencing currency devaluation, inflation, food shortages and shrinking foreign currency reserves, the central government will have difficulty in implementing a development-based solution in Sinai.

This article first appeared in the December 15 2016 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.