Andrew McGregor

March 1, 2019

Ten weeks into massive street protests in Sudan, anger at the three-decade-old regime of President Omar al-Bashir has begun to spread well beyond Khartoum. Unsure of support from the army (supposedly his powerbase), Bashir has unleashed counter-terrorist paramilitaries against the demonstrators. Though the 75-year-old Bashir continues to resist calls for his resignation, he is unlikely to continue his iron-hand rule of Sudan for much longer. With religious extremists active in Sudan and continuing insurgencies throughout the country, there is a strong possibility the nation might experience a rapid deterioration in security following a regime collapse, one which would quickly have regional consequences.

While al-Bashir might survive the latest protests through brute repression, he has experienced ill-health in recent years and is facing opposition even amongst his base against running for re-election in 2020. The circumstances raise the question of whether terrorism and counter-terrorism will develop in new or novel ways in a post-Bashir Sudan.

While al-Bashir might survive the latest protests through brute repression, he has experienced ill-health in recent years and is facing opposition even amongst his base against running for re-election in 2020. The circumstances raise the question of whether terrorism and counter-terrorism will develop in new or novel ways in a post-Bashir Sudan.

Foreign debt, economic mismanagement, inflation and shortages of foreign currency have plagued Sudan since the separation of South Sudan in 2011 and the consequent loss of the enormous oil revenues supplied by wells in the south. Protesters have connected this economic deterioration with the authoritarianism of the regime in their calls for immediate change. The growing death toll on the streets of several Sudanese cities reflects how serious the regime takes these protests – popular uprisings supported by elements of the army succeeded in deposing Sudanese regimes in 1964 and 1985.

The Governing Military-Islamist Alliance

Sudan’s rather unique military-Islamist regime is the result of Sudan’s Muslim Brotherhood (the Ikhwan) seeking firepower and muscle to enable them to overthrow the elected but ineffectual government of Sadiq al-Mahdi and establish an Islamic regime in 1989. Finding little support for this project amongst the military’s senior staff, Brotherhood leader Dr. Hassan al-Turabi (1932-2016) turned to more junior officers, especially Omar al-Bashir, who would leap from Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) major to Sudanese president overnight as the figurehead of the coup.

One of the major grievances of Sudan’s highly diverse population is the nation’s political domination since independence by members of three Nile-dwelling Arab tribes from North Sudan – the Danagla, the Sha’iqiya and the Ja’alin (al-Bashir is a Ja’ali).

The Islamist movement that propelled al-Bashir to power split in 1999, with its leading member, al-Turabi, leaving to form the opposition Popular Congress Party (PCP). Other Islamists remained with the ruling National Congress Party (NCP), which has seemed more dedicated to preserving the regime than promoting an Islamic social transformation in Sudan. The NCP is currently preoccupied with internal rifts.

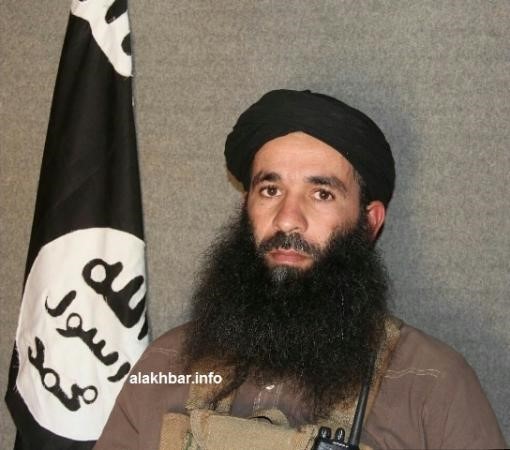

Shaykh al-Zubayr Muhammad al-Hassan

Shaykh al-Zubayr Muhammad al-Hassan

The NCP is supported by the Sudan Islamic Movement (SIM), which is intended to provide ideological guidance. In the midst of the economic crisis, SIM leader al-Zubayr Muhammad al-Hassan praised the regime for creating a “much better economic situation” and drastically lowering poverty rates. In reality, the country has been propped up in recent years with heavy financial assistance from the Gulf States. Few Sudanese could agree with al-Zubayr’s perception, but many would agree with his observation that opportunities had been created for “a number of Islamists” (Radio Dabanga, August 28, 2018).

Ansar Protesters Gather outside the Hijra Wad Nubawi Mosque in Omdurman (Radio Dabanga)

Ansar Protesters Gather outside the Hijra Wad Nubawi Mosque in Omdurman (Radio Dabanga)

Mosques have become gathering points for protesters, particularly after Friday sermons denouncing the “tyranny and corruption” of the regime. As a result, various mosques have been stormed by security forces firing tear gas, including the Hijra mosque in Wad Nubawi (Omdurman), home of the powerful Ansar Sufi movement led by two-time prime minister Sadiq al-Mahdi (Radio Dabanga, February 17).

Tear Gas strikes the minaret of al-Hijra Wad Nubawi Mosque on January 11, 2019 (Pan-African News-wire)

Tear Gas strikes the minaret of al-Hijra Wad Nubawi Mosque on January 11, 2019 (Pan-African News-wire)

A Partner in Counter-Terrorism?

Khartoum has enjoyed quiet U.S. support as a counter-terrorism partner despite the regime’s Islamist base. To reward Sudan for cooperation on the counter-terrorism file and progress on several other issues, U.S. President Barack Obama lifted a long-standing American trade embargo in one of the last acts of his presidency. [1] Sudan, however, has remained a designated state sponsor of terrorism since 1993 and is still subject to certain sanctions as a result.

Sudanese Foreign Minister al-Dardiri Muhammad Ahmad visited Washington in November 2018, where he claimed to have convinced Trump administration officials that Sudan has made major progress on human rights and counter-terrorism issues. However, some of al-Dardiri’s remarks were somewhat disconcerting, such as when he insisted Osama bin Laden had “nothing to do with terrorism” during his presence in Sudan. Al-Dardiri claimed Bin Laden was only occupied with developing an airport with his construction team (VOA, November 1, 2018). Al-Dardiri also pointed out that Khartoum understood the world is no longer unipolar. China, Russia and Turkey were all ready to step up with aid and debt write-offs without regard to Sudan’s status as a state sponsor of terrorism (Foreign Policy, November 8, 2018).

Islamic Extremism in Modern Sudan

The Bashir regime has had an ambiguous relationship with extremist groups inside Sudan, partly as a result of the ebb and flow of Islamist influence within the government. In 1991, Muslim Brotherhood leader Hassan al-Turabi persuaded the regime to host Osama bin Laden and his followers until they were expelled in 1996 when they came to be identified as an internal threat. The sporadic emergence of other Sudanese extremist groups in some cases came to be recognized as little more than paper claims for the deeds of others.

A group called “al-Qaeda in Sudan and Africa” claimed responsibility for the July 2006 kidnapping and beheading of Muhammad Taha Muhammad Ahmad, the Islamist editor of Khartoum’s al-Wifaq newspaper, for “dishonoring the Prophet.” Authorities instead hanged nine members of the Fur ethnic group for the offense, despite claims by the suspects that they had been tortured into confessions. Their motive was alleged to be revenge for Muhammad Taha’s articles claiming that well-documented reports of mass rape by government security forces in Darfur were nothing more than consensual sex (Sudan Tribune, April 14, 2009; Sudan Tribune, April 16, 2009).

In 2008, gunmen belonging to the small Ansar al-Tawhid (Supporters of Monotheism) group murdered USAID employee John Granville and his Sudanese driver in the streets of Khartoum. The attack on Granville came only one day after then U.S. President George Bush signed the Sudan Accountability and Divestment Act, a bill drafted in response to Khartoum’s alleged genocide in Darfur. Suspicions of official sanction for the attack were reinforced when four members of the group made a video-taped escape from North Khartoum’s Kober Prison in 2010 while awaiting execution. It was the first escape from the colonial-era prison. Suspicions were revived when two men convicted of orchestrating the escape from outside were given early presidential pardons (Sudan Tribune, August 15, 2015; Radio Dabanga, April 7, 2016). The attack was also claimed by an apparently imaginary group called “al-Qaeda in the Land of the Two Niles,” but ultimately none of the suspects were charged with membership in a terrorist group (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, October 12, 2008).

One of the escapees in the Granville case was ‘Abd al-Ra’uf Abu Zayid Muhammad, the son of the leader of Ansar al-Sunna al-Muhammadiya, the largest Salafist group in Sudan. Sudanese Salafism is primarily of the quietest type with minimal political involvement, consistent with Salafist beliefs in the legitimacy of political leadership in Muslim nations, which can only be challenged in extreme circumstances such as the repudiation of Islam. However, there exists a strong rivalry with Sufism, the deeply rooted and dominant form of Islamic worship in Sudan, as well as between different Salafist groups. Ansar al-Sunna became engaged in a doctrinal dispute with the Salafist Takfir wa’l-Hijra (Renunciation and Exile) movement in the 1990s, leading to a series of three attacks on Ansar al-Sunna mosques that left a total of 54 people dead (see Terrorism Focus, February 6, 2009).

In December 2012, Sudanese security forces fought an eight-hour gun battle with Salafi-Jihadists at their training camp in Dinder National Park in Sinnar Province (east Sudan). The group was composed largely of university students from Khartoum but was not associated with al-Qaeda, according to authorities (Akhir Lahza [Khartoum], December 4, 2012).

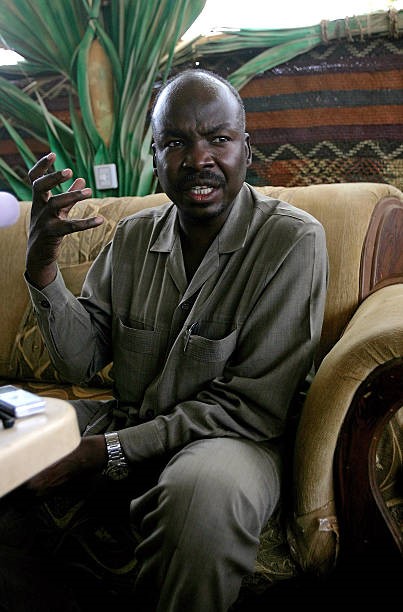

Muhammad ‘Ali al-Jazouli

Muhammad ‘Ali al-Jazouli

In 2015, it was learned that medical students, primarily dual-citizens from the UK, Canada and the United States, were being recruited from Khartoum’s University of Medical Science and Technology to serve in Islamic State medical facilities in Syria (Sunday Times, February 5, 2017). At the time, a prominent Khartoum imam, Muhammad ‘Ali al-Jazouli, was advocating for the Islamic State and encouraging Muslims to kill “infidel” women and children. The imam was jailed for eight months and then quickly re-arrested after it became apparent his beliefs had not changed (Radio Dabanga, July 1, 2015).

The following year, Sudan’s Interior Minister admitted there were as many as 140 Sudanese Islamic State members (mostly operating abroad in Syria, Iraq and Libya), adding that they did not present a threat to Sudan (Assayha.net, July 14, 2016). The actual number could be significantly higher.

Is Intervention by the Sudan Armed Forces Possible?

Opposition calls for the army to step in and depose al-Bashir have had little apparent resonance so far. After repeated purges, the officer corps of the SAF is largely Islamist and has little interest in enabling regime change for any other party. With the exception of a few members of al-Bashir’s inner circle, the SAF appears to be taking a wait-and-see approach to the street demonstrations, offering little in the way of open support or opposition to al-Bashir. The most likely scenario for an early exit by the president could involve transferring power to the army in preparation for new elections. Al-Bashir has hinted he would have no objection to handing over power to “a person wearing khaki” (a military man) but has otherwise held to a defiant course, maintaining that the protesters were only hired mercenaries and heretics (Sudan Tribune, January 9; Arab News, January 21).

Lieutenant General Kamal ‘Abd al-Marouf, SAF chief-of-staff

Lieutenant General Kamal ‘Abd al-Marouf, SAF chief-of-staff

Soon after reports emerged of military officers joining protests in three Sudanese cities, SAF command released a statement confirming that it “stood behind the nation’s leadership” (Anadolu Agency, December 24, 2018). National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS – Jiha’az al-Amn al-Watani wa’l-Mukhabarat) chief Saleh Gosh and the SAF’s chief of general staff, Kamal ‘Abd al-Maruf, publicly proclaimed the army’s full support for al-Bashir, with the latter dismissively insisting the army would never hand over the country to “homeless” protesters (Sudan Tribune, January 30; Sudan Tribune, February 10).

The regular army has had little direct involvement in repressing the street protests, which are dealt with largely by elements of the pro-Bashir police, the NISS and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF – Quwat al-Da’m al-Seri), the latter a poorly disciplined paramilitary composed mostly of Darfur Arabs. Some are veterans of the notorious Janjaweed. The president’s security institutions have used all the tools of a repressive state to control and suppress Islamist extremists (or even manipulate them when desired), but unleashing the “counter-terrorist” RSF against unarmed civilians will not be viewed favorably by most Sudanese.

The NISS is a pervasive and pernicious presence in Sudanese society, enjoying broad immunity from prosecution while deploying their extensive powers of arrest, censorship, property seizure and even indefinite detention and abuse in so-called “ghost houses” that exist outside the judicial system. Of late, the NISS has been receiving training from Russian mercenaries (see EDM, February 6).

The director of the NISS is Saleh Gosh, a Sha’iqiya Arab and top intelligence figure who was retrieved from the political wilderness to provide unflinching support to the regime. Gosh, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood who was the regime’s point man with Bin Laden during his time in Sudan, later became close to the CIA during his first tenure as NISS chief, supplying important information about al-Qaeda and other Islamist terrorist groups. As Gosh revealed in 2005 during the regime’s brutal suppression of the revolt in Darfur: “We have a strong partnership with the CIA. The information we have provided has been very useful to the United States” (LA Times, April 29, 2005).

Gosh had a major role in purging the regime of al-Turabi’s supporters in 1999 but lost his job a decade later when his rivalry with presidential advisor Nafi al-Nafi began to weaken the regime. In November 2012, NISS agents arrested Gosh and several senior Islamist officers of the SAF—including the popular General Muhammad Wad Ibrahim ‘Abd al-Jalil, former commander of the presidential guard—on suspicion of preparing a coup d’état. [2] Gosh was released several months later due to a lack of evidence but remained uncritical of the regime. He was rewarded in February 2018 when al-Bashir re-appointed him as NISS director (Fanack.com, March 28, 2018). Gosh has since cleansed the NISS of those not completely loyal to al-Bashir, even though Gosh himself remains a potential presidential successor.

President Omar al-Bashir (left) with ‘Ali Osman Muhammad Taha

President Omar al-Bashir (left) with ‘Ali Osman Muhammad Taha

Another possible Islamist successor is ‘Ali Osman Muhammad Taha (Sha’iqiya), a civilian who was once Hassan al-Turabi’s chief lieutenant in the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood. Taha re-aligned himself behind al-Bashir and the NCP after the 1999 Islamist split. Sudan’s Foreign Minister in the turbulent 1990s, Taha was appointed first vice-president in 1998, a post that he held twice until his final dismissal by al-Bashir in 2013. Since then, there has been a trend away from civilian Islamists in the nation’s top posts toward the appointment of Islamist-inclined senior army officers. Taha remains highly influential in Sudan’s Islamist movement, though his international reputation was damaged by his central involvement in the regime’s ethnic cleansing of Darfur (Fanack.com, November 30, 2016). Opposition members have accused Taha’s Islamist supporters (the “unregulated brigades” he warned protesters about) of assault on demonstrators and the use of live-fire (al-Sharq al-Awsat, January 21).

Unresolved Rebellions

Most of Sudan’s budget is dedicated to its endless internal conflicts, with over 70 percent of spending allocated to defense and security matters (Radio Dabanga, August 28, 2018). In effect, the regime devotes nearly all its resources to defending itself from internal opposition.

The SAF is engaged in the expensive repression of long-standing rebellions on three fronts: Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile State. The four leading rebel movements, grouped as the Sudanese Revolutionary Front (SRF), renewed their unilateral ceasefire for a further three months on February 9 (Sudan Tribune, February 10). [3] Though somewhat exhausted from years of campaigning, these groups are still capable of confronting government security forces and may be using Khartoum’s focus on the protests to replenish and rebuild. Despite the viciousness with which these conflicts are fought, Sudan’s rebel movements continue to eschew urban terrorism in favor of more “conventional” guerrilla tactics.

On December 28, 2018, the Sudanese government claimed to have captured armed members of Darfur’s SLM/A-AW rebel group in the North Khartoum suburb of al-Droushab, over 500 miles from the group’s normal operational zone in the Jabal Marra region of Darfur. Security forces broadcast footage of young detainees confessing their intention to kill protesters, destroy property and attack public institutions. The SLM/A-AW refuted the charges, calling them “blatantly fabricated allegations” while insisting the movement’s operations were confined to Jabal Marra (Sudan Tribune, December 30, 2018).

Security Prognosis

Sudanese insularity and widely based self-perception as leaders rather than followers in the development of political Islam (dating back to the anti-imperialist Mahdist movement of the late 19th century) has helped to inhibit the local growth of foreign-based extremist groups such as al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. Nonetheless, Sudan’s economic crisis will not suddenly cease if al-Bashir steps down, leaving a moderate possibility that foreign terrorist groups may try to exploit political instability to establish a presence in Sudan.

Islamists may find it hard to find space within a new post-Bashir regime, much as was the case when the Islamist-influenced President and former general Ja’afar Nimeiri was overthrown in 1985. Closely tied to al-Bashir, there is a good chance the NCP could collapse soon after a change in the presidency, leaving room for new actors and the traditional parties to explore after years of exclusion from power. Convinced of their religious duty, Islamists have turned to violence elsewhere after being ejected from power. Certain Islamist factions will thus remain a danger to the emergence of a more secular government, but a descent into urban terrorism remains unlikely, due in large part to the broader population’s revulsion for the targeting of innocents. The carefully-planned coup, the lightning raid and the protracted defense of rough terrain are all more acceptable methods of armed struggle in Sudan, though the growth of terrorism in neighboring countries means new strategies of violence are never far away.

Shortly before his death, former Muslim Brotherhood leader Hassan al-Turabi made a terrible prediction for the future of Sudan: “The revolution, if there is any, will not be like [the earlier uprisings]. The whole Sudan now is armed, though any violence will quickly spread across the whole country, and the situation will be worse than Somalia, Iraq, because we are from different tribes, and types” (Sudan Tribune, July 7, 2015). So far, the uprising has had more of a unifying effect, but the potential remains for a general security breakdown with daunting prospects for regional security.

Notes

1, See: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/13/executive-order-recognizing-positive-actions-government-sudan-and January 13, 2017.

2. See: Andrew McGregor, “Sudanese Regime Begins to Unravel after Coup Reports and Rumors of Military Ties to Iran,” AIS Special Report, January 7, 2013, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=141

3. SRF members include Minni Minawi’s Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A-MM), al-Hadi Idris Yahya’s Sudan Liberation Movement – Transitional Council (SLM-TC), Malik Agar’s Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army – North (SPLM/A-N) and the Justice and Equality Movement led by Jibril Ibrahim.

This article first appeared in the March 1, 2019 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

The founding of JNIM: Yahya Abu al-Hammam (left), Iyad ag Ghali (center), Abu Hassan al-Ansari (right, killed by French forces in February 2018).

The founding of JNIM: Yahya Abu al-Hammam (left), Iyad ag Ghali (center), Abu Hassan al-Ansari (right, killed by French forces in February 2018).