Andrew McGregor

May 18, 2012

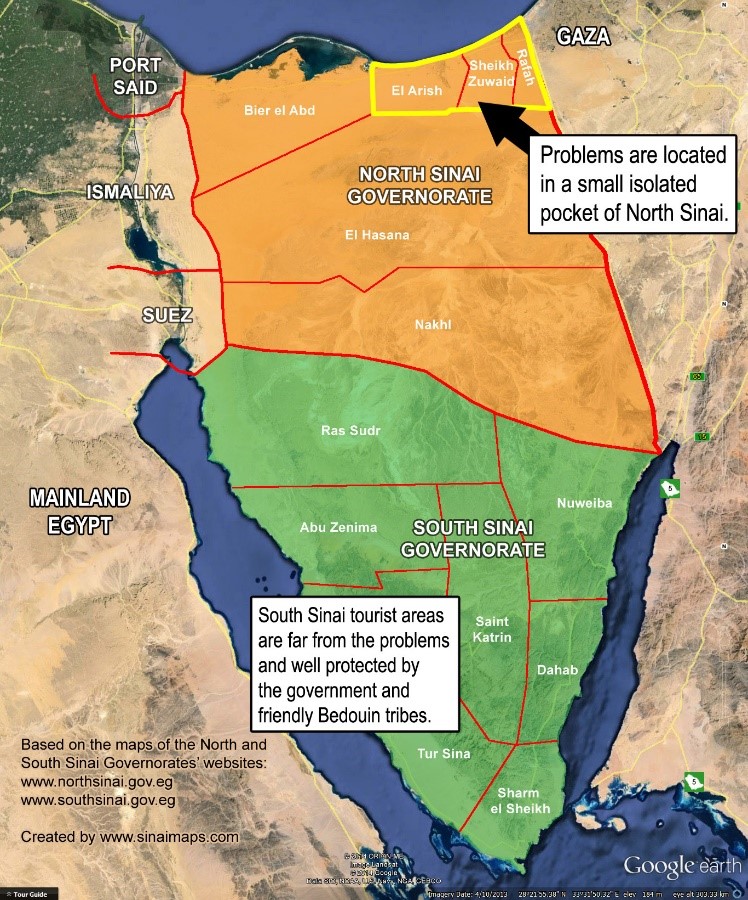

Though Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula has just marked its 30th anniversary of liberation from Israeli occupation, the region is perhaps less integrated with the rest of the Egyptian state now than at any time since the Camp David Accords returned sovereignty of the Sinai to Cairo. An influx of arms from Libya and elsewhere is fuelling a growing insurgency amongst an alienated and disenfranchised population and deteriorating relations between Egypt and Israel are threatening to once more make the Sinai borderlands a battleground between these regional rivals.

The Sinai: Northern Deserts and Southern Mountains

Egyptian security authorities blame most of the scores of attacks on police since the January 25, 2011 Egyptian uprising on Gaza-based Palestinian militant groups such as Jaljalat, Jaysh al-Islam, Izz al-Din al–Qassam and the local al-Qaeda in the Sinai Peninsula (Egypt Independent, May 1). [1] However, while radical Islamism and close ties to Palestinian militants in Gaza play an important role in the unrest, there is little question that the core of the Sinai insurgency consists of armed Bedouin who exist largely on the fringes of Egypt’s Nile and Delta-based society.

Law enforcement has declined in the Sinai to the point that the police exist mainly to protect police installations that increasingly resemble improvised fortresses protected by large sand berms and steel walls to repel RPG attacks. The security situation is not helped by continuing protests against the military government by disgruntled police across Egypt, including in the towns of the northern Sinai. The Bedouin tribesmen have little fear of government authorities – security checkpoints are routinely attacked and security men and soldiers assassinated.

The Bedouin Factor

Tribal chiefs have issued demands for the establishment of a free trade zone and open passage for trade between Gaza and the Sinai, a move that would provide much needed employment and opportunity for local tribesmen, but which is unlikely to ever receive the necessary approval of Israel (MENA, April 21). It is estimated that 90% of the Bedouin population is unemployed and prevented by law from seeking employment in either the security services or the resorts of southern Sinai. The Bedouin are demanding the right to participate in the local security apparatus, but the idea has met resistance in Cairo where lingering questions about Bedouin loyalty to the state have deterred providing the Bedouin with modern arms and training. The release of Bedouin prisoners seized before last year’s Egyptian Revolution and the right to own land are also high on the Bedouin agenda.

The military government used the Liberation Day holiday to announce the commitment of $66 million to development projects in the northern Sinai, the largest project involving an upgrade to the port at al-Arish (Ahram Online, April 25). Further agreements to initiate a labor-intensive extension of water supply lines in north and south Sinai were signed the next day (Bikya Masr [Cairo], April 26). However, there is little chance of significant progress being made until after Egypt’s presidential elections, a multi-staged process which will begin on May 23.

The Sinai as Election Issue

As the elections approach, it has become clear that local issues in the Sinai have become irretrievably interwoven with Egypt’s changing relationship with Israel, as revealed by an examination of the platforms of several leading candidates:

- Moderate Islamist candidate Muhammad Salim al-Awa has called for negotiations with Israel to amend the Camp David treaty in areas “that go against Egypt’s interests, like dividing the Sinai into three demilitarized zones, allowing Israelis into the Sinai without visas and other privileges given to Israel that should stop immediately” (Al-Ahram Weekly, May 10-16).

- Amr Moussa, a secular candidate and former chairman of the Arab League, has called for a new agreement with Israel for the export of Egyptian natural gas across the Sinai based on current global market prices, adding that Israel must abandon its “policy of intransigence, threatening, [development of] settlements, occupation and [allow] the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state” (Business Today Egypt, May 8). Moussa has promised to restore stability in the peninsula, end the marginalization of the Bedouin tribes and overturn the prohibition against Bedouin owning land in the Sinai (Ahram Online, April 21).

- Neo-Nasserist candidate Hamdeen Sabahi (Karame Party) has promised to create a new local police force that is in tune with the rights and traditions of the Bedouin as part of an effort to turn the Sinai into “a paradise.” Nonetheless, his recent visit to the peninsula was cut short after receiving threats on his life from a Salafist group in the northern Sinai town of Shaykh Zuwayid despite promising to release all Bedouin political prisoners and suspected militants without conditions if elected (Ahram Online, April 21; April 29)

- Muhammad Mursi, the head of the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party, has called for urban development in the Sinai and the resettlement of millions of Egyptians in the sparsely inhabited region as Egypt’s population surges towards the 90 million mark, far more than can be comfortably supported in the Delta region and the slim fertile strip along the Nile (Ahram Online, April 29). A message from Muslim Brotherhood leader Muhammad Badi on April 26 said that the Mubarak regime had persecuted the Bedouin as criminals when they were, in fact “patriotic citizens.” Badi added that a mass transfer of Egyptians to the Sinai from other parts of Egypt would “frustrate Zionist ambitions to seize Sinai once again” (EgyptWindow.net, April 27).

However, these pledges have had only limited resonance with the Sinai Bedouin. As North Sinai Bedouin writer Ashraf Ayoub put it, “Sinai doesn’t need promises – what it really needs is reconciliation between the locals of Sinai and the rest of Egypt which looks at them like foreigners who plot against the country. We are more than a group of people who live in a strategic location” (Ahram Online, April 29).

In the meantime there is growing evidence that Libya’s looted armories are now being used to equip militants in the Sinai much as they have provided modern weaponry to militants in parts of North and West Africa. Egyptian security forces reported the seizure on May 10 of a large quantity of weapons being transferred to the Sinai for use against Egyptian security forces by a convoy heading east from the Mediterranean port city of Mersa Matruh. Among the weapons were 50 surface-to-surface rockets, 17 grenade-launchers, seven assault rifles, a mortar and a large quantity of ammunition. The three smugglers arrested were reported to be Sinai Bedouin (Daily Star [Beirut], May 10; AP, May 10).

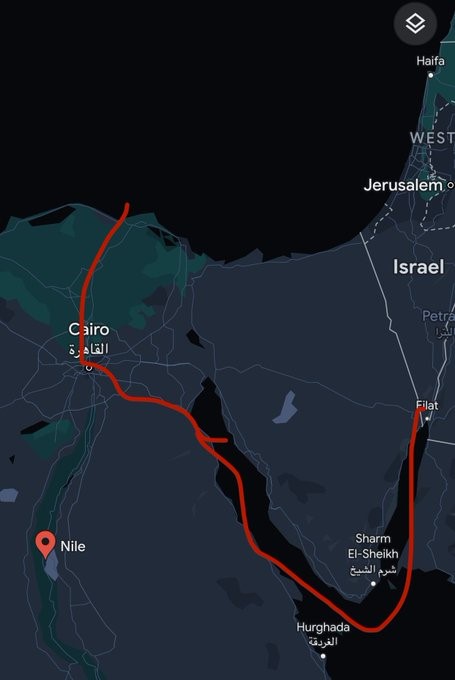

Israeli authorities announced on April 5 that one or two rockets possibly of Libyan origin had been fired at the Israeli Red Sea port of Eilat from the Egyptian Sinai, though Egyptian spokesmen claimed Israel was only “spreading rumors” (Al-Quds al-Arabi, April 7; NOW Lebanon, April 10; AP, May 10). Israel is preparing to link Eilat to an early-warning system in anticipation of further rocket attacks from Egypt.

Israel sees the hand of Shiite Iran behind the turmoil in the Sunni Sinai. According to Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu: “The Sinai is turning into a kind of “Wild West” which … terror groups from Hamas, Islamic Jihad and al-Qaeda, with the aid of Iran, are using to smuggle arms, to bring in arms, to mount attacks against Israel” (Voice of Israel Network B, April 24). Egyptian security sources are reported to have expressed their own suspicions of Iranian funding for weapons transfers from Libya to Sinai, though Iran has denied any such activities (al-Sharq al-Awsat, May 8). Egypt and Iran have not had diplomatic relations since Egypt’s recognition of Israel in 1980, though efforts have been underway to re-establish relations since the overthrow of Mubarak.

Severing Israel’s Natural Gas Supply

A persistent irritant in Egyptian-Israeli relations are the long-term contracts for the supply of Egyptian natural gas to Israel at below market rates negotiated by corrupt businessmen within the inner circle of former president Hosni Mubarak. With the pipeline to Israel having been blown by Sinai-based militants 14 times since Mubarak was deposed in January 2011, Egypt finally announced on April 23 that the natural gas agreement had been scrapped. The pipeline, which has not been operational since March 5, was last bombed on April 9 when militants mistakenly believed it had been returned to use after noting the Interior Ministry had sent some 2,000 Special Forces officers to guard it (Ma’an News Agency, April 9; April 15). A dispute over missing payments appears to have been the main cause for the termination of the contract.

An official in Egypt’s oil ministry commented: “It was a popular demand to call off this treaty, as we export gas to [Israel] cheaper than market prices… Their error was not to pay on time, and we have taken the opportunity to stop this shameful deal” (Bikya Masr [Cairo], April 23).

According to an official of the East Mediterranean Gas Company (EMG), Egypt has the right “to cancel its contract with the company as… [Israel] has not paid its commitments for several months…” (al-Hayat, April 29). EMG was founded by fugitive financier Hussein Salim, a former crony of Mubarak. However, international shareholders in the EMG are trying to paint the cancellation as a political move as the basis for an $8 billion lawsuit (Ahram Online, May 3). A statement from the shareholders claims that the Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company (ENGH) failed to protect the pipeline, though the latter describes the repeated bombings of the pipeline as a force majeure situation and insists that it was non-payment for gas received that led to the cancellation of further shipments in line with the terms of the contract (al-Hayat, April 27).

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has tried to downplay suggestions that Egypt’s cancellation was a form of aggression against Israel by confirming the decision was part of a “legal-commercial dispute” that would not have long-lasting effects due to the development of natural gas resources in the Mediterranean that would make Israel “a major exporter of natural gas in the world” (Voice of Israel Network B, April 24).

A Greater Threat to Israel than Iran?

Israeli foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman recently described Egypt as “more troubling than the Iranian issue” and advised Prime Minister Netanyahu to move three to four divisions up to the Sinai border, complaining that the seven Egyptian battalions currently operating in the Sinai “aren’t carrying out real antiterrorism activities” (Ma’ariv [Tel Aviv], April 22). Though offered several opportunities to do so, Lieberman has not backed away from his assessment that Egypt will commit a major violation of the 1979 peace treaty after the upcoming presidential election in order to unite the nation around a common enemy.

The publication of Lieberman’s remarks was followed by an immediate request by Egypt’s foreign minister Muhammad Kamel Amr for “clarification” on their accuracy (Ahram Online, April 24). Lieberman’sassertion was also challenged by Israeli Defense Minister Ehud Barak: “The Iranian threat is a threat with existential potential. At the moment this is not the case [with Egypt]…” (Globes Online [Rishon Le-Zion], April 25).

Israel’s Counterterrorism Bureau issued a warning on April 21 for all Israelis in the Sinai to leave the region and return to Israel after it claimed to have determined that terrorists were planning an attack against resorts in the southern Sinai that are highly popular with Israeli tourists (Ahram Online, April 21). However, the warnings appear to have had little resonance with Israeli holiday-makers in search of a cheap vacation, with border authorities reporting more Israelis entering Egypt than leaving and resort owners in South Sinai reporting that most hotels were fully booked (Jerusalem Post, April 23). South Sinai Governor Major General Khalid Fouda suggested that Israel spread rumors of imminent terrorist attacks whenever Egypt’s tourism industry showed signs of recovery from the low point reached during the 2011 revolution (Ahram Online, April 21).

Members of the largely Bedouin “Sinai Revolutionaries Movement” attempted to strike a symbolic blow against Israel on Liberation Day by planning to paint an Israeli memorial in the Sinai to ten Israeli soldiers killed in a helicopter crash during the Israeli occupation with the Egyptian colors (al-Youm al-Saba’a [Cairo], April 25). The effort was prevented by Egyptian security forces who are obliged to protect the memorial under the terms of the Camp David agreement. Israel in turn maintains a memorial to fallen Egyptian troops in the Negev Desert. A spokesman for the northern Sinai tribes, Abd al-Mun’im al-Rifa’i, said the people of the Sinai reject this provision of the treaty and cited a “need to demolish the rock [i.e. the memorial in the form of a large rock] because it stands as a provocation” to the Sinai tribes who “do not want any memorial for the Zionist entity on their land” (al-Hayat, April 27). The movement cites Israel’s reluctance to agree to a greater Egyptian security presence in the Sinai as a principal cause of the region’s instability (Ma’an News Agency [Bethlehem], April 12). Annex 1 of the Camp David Accords divides the Sinai Peninsula into four zones running roughly north-south (“Zones A to D”), with the Egyptian security presence in each zone decreasing as they grow closer to the Israeli border. Any change to these deployments must be made with the agreement of the Israeli government, severely limiting Cairo’s ability to meet security challenges in the Sinai.

A state-controlled Egyptian media source suggested it was time to “change the rules of the game” imposed on Egypt by the Camp David agreement:

It is no longer acceptable to tolerate tipping the balances of power in favor of the Israeli enemy. It is no longer possible to submit to conditions of capitulation that undermine Egypt’s sovereignty or allow its resources to be stolen. It is no longer possible to be tolerant with Israel’s conspiracies against Egypt’s interests in the waters of the Nile (al-Akhbar, April 29).

In an effort to permanently cut off Hamas-governed Gaza from Egypt, Israel is constructing a new security barrier along its border with Sinai that is expected to be finished later this year. The new fence will be five meters high, covered in barbed wire and augmented by dozens of radar installations. 120 km have been finished so far, with work continuing on a further 100 km (Jerusalem Post, April 25). After five failed attempts, the new fence was successfully breached by Bedouin smugglers using hydraulic tools in early May, though the infiltrators were quickly caught by the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) (Arutz Sheva [Tel Aviv], May 2; Times of Israel, May 2).

Israel is also increasing its military presence along the border. The IDF’s 80th “Edom” Division has experienced significant upgrades since it was redeployed along the Sinai border following cross-border attacks last August (Ma’ariv [Tel Aviv], April 6). In addition, the IDF announced call up orders for an additional six battalions to man the Sinai and Syrian borders on May 3 (Arutz Sheva [Tel Aviv], May 3).

Last month, Egypt’s Second Army commenced Nasr-7, one of the largest live-fire exercises carried out in years in the Sinai. The commander of the Second Army, Major General Muhammad Farid Hijazi, announced that the Egyptian military was fully capable of defending the Sinai against attacks from any quarter (MENA, April 23). Field Marshal Muhammad Hussein Tantawi, the head of Egypt’s military government, adopted a belligerent tone during the exercise, telling troops of the Second Army: “We will break the legs of anyone who dares to come near to the borders” (Ahram Online, April 23).

International Peacekeepers under Pressure

Attempting to ensure that the security provisions of the Camp David agreement are maintained is the Multinational Force and Observers (MFO), consisting of some 1400 soldiers and civilians from 12 nations, including 800 Americans operating as a sub-unit known as “Task Force Sinai.”

With the parties of the 1978 peace treaty having failed to obtain backing for a UN peacekeeping force, the MFO was created in 1981 as an alternative, equipped with a mandate to supervise the security provisions of the treaty and to use its influence to prevent treaty violations. Financing for the force is divided three ways between the United States, Israel and Egypt.The MFO deployment began on April 25, 1982, as Israel withdrew from the Sinai and returned sovereignty to Egypt. Increasingly, however, the MFO is finding its ability to carry out its mission restricted by growing levels of militancy in the Sinai.

In mid-March, some 300 Bedouin armed with automatic rifles surrounded a MFO base holding hundreds of U.S., Colombian and Uruguayan troops to pressure Cairo to release five tribesmen facing possible sentences of death or life in prison for their alleged role in the 2005 bombings of the Sharm al-Shaykh resort in southern Sinai (Ahram Online, March 15). On May 7, ten Fijian soldiers belonging to the MFO were kidnapped along the Auja-Arish highway in northern Sinai by Bedouin demanding the release of several tribesmen from prison. The Fijians were released later that day following negotiations with Egyptian authorities in which the kidnappers were assure their demands would be met (Ahram Online [Cairo], May 7; AFP, May 7).

Conclusion

While Egyptian relations with Israel continue to cool, the interim military government in Cairo has no wish to become involved at this point in a military confrontation with Israel sparked by the activities of militant groups in the Sinai. While Field Marshal Tantawi talks tough about defending Egypt’s borders, he and the rest of the military command are aware that even defensive clashes with the IDF could jeopardize ongoing U.S. funding of the Egyptian military, particularly in a sensitive election year in the United States. At the same time, Israeli demands for greater security in the peninsula cannot be met without revisions to those parts of the Camp David treaty governing the number of troops and types of military equipment that can be deployed there. Most important, however, is the need to address the long-standing grievances of the indigenous Bedouin population who find themselves unhappily trapped on a traditional Egyptian-Israeli battleground while held in suspicion by both parties. In the absence of meaningful efforts to resolve their economic and social issues, the Bedouin will continue to find themselves attracted to militancy, a situation that has the potential of igniting a new Middle Eastern conflict.

Note

1. For al-Qaeda in the Sinai Peninsula, see Andrew McGregor, Jamestown Foundation Hot Issue, “Has al-Qaeda Opened a New Chapter in the Sinai Peninsula?,” August 17, 2011, http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=38332

This article first appeared in the May 18, 2012 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor

General Alfredo Stroessner, Dictator of Paraguay

General Alfredo Stroessner, Dictator of Paraguay Israeli Intelligence Minister Gila Gamliel (X)

Israeli Intelligence Minister Gila Gamliel (X) Israeli Minister of Finance Bezalel Smotrich (Israel Hayom)

Israeli Minister of Finance Bezalel Smotrich (Israel Hayom) “An Integral Part of Israel” – Israel’s Projected New Western Border

“An Integral Part of Israel” – Israel’s Projected New Western Border General Giora Eiland (Jerusalem Post)

General Giora Eiland (Jerusalem Post) Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry (Daily News Egypt)

Egyptian Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry (Daily News Egypt)