Andrew McGregor

AIS Special Report on Ukraine no. 7.

November 9, 2022

Islamist extremists in Mali are attempting to prevent the harvest of various food crops, vitally needed in the midst of food shortages and rising food prices caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Earlier this year the jihadists tried to prevent farmers from planting, but Malian troops were sent to guard the farmers. Now, with the harvest ready to start, farmers are again coming under fire in their fields. Militia leader Youssouf Toloba has called on traditional hunters of the Dogon ethnic-group to support the Malian military in its efforts to protect the farmers (Le Soir de Bamako, October 17, 2022). Toloba is the so-called “chief of the general staff” of the Dan Na Ambassagou, a group of Dogon hunters who have formed a “self-defense” militia to defend the Dogon from Islamic State and al-Qaeda-associated jihadists operating almost at will in Mali.

The Black Sea Corridor and Global Food Security

The jihadists are following Russia’s lead in weaponizing food security. For months after the February invasion of Ukraine, Moscow imposed a blockade of the Ukrainian Black Sea coast, the only real means of exporting Ukraine’s massive production of grain and other food products to the rest of the world.

A July 22 agreement negotiated by the UN and Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan to allow the shipment of Ukrainian grain and fertilizer through Russia’s naval blockade is set to expire on November 19. By October 19, negotiations with Russia for an extension to the Black Sea safe corridor had already begun to founder after Ukraine invited UN experts to examine the remains of Russian drones allegedly made in Iran. A Russian diplomat warned that any “illegitimate investigation” into the drones’ origins would force Russia to “reassess” its collaboration with the UN (Reuters, October 19, 2022).

On October 29, Russia suspended the agreement, warning of potential danger to ships defying Russia’s blockade. This time the cause was an alleged Ukrainian attack on Russian warships at the naval port of Sevastapol. The alleged attack, using both naval and aerial drones, was said to have damaged several ships, including a modern Admiral Grigorovich class frigate (NATO reporting name “Burevestnik”), probably the Admiral Makarov, flagship of the Russian Black Sea fleet since the April 14 sinking of the old flagship Moskva by Ukrainian Neptune missiles (Euromaidanpress.com [Kiev], November 1). Russia admits only to damage to a minesweeper. The Admiral Makarov and other ships of the Black Sea fleet are valuable targets, having been used to launch Kalibr cruise missiles into Ukraine during Russia’s ongoing missile offensive.

Russia’s defense ministry claimed to have captured an intact UAV used at Sevastapol and examined its memory to determine it had flown along the safe corridor. The ministry suggested it may have been launched from one of the civilian ships carrying Ukraine’s agricultural products (al-Jazeera, November 3, 2022). Moscow has also claimed that Russian food exports remain restricted by sanctions and other measures despite assurances provided in the Black Sea safe corridor agreement.

However, Russia’s warning failed to stop shipments of Ukrainian grain and sunflower oil; a new record was in fact set on October 31 for shipping Ukrainian goods through the safe corridor established in July (354,000 tonnes). With the Turkish president once more taking the role of mediator to assure the continuance of the agreement, vital to world food supplies, Russia was left with a hard choice; continue issuing ineffective warnings that would ultimately become embarrassing if they continued to be ignored, attack international cargo ships carrying grain and oil from Ukrainian ports (which would produce global condemnation, even from its allies), or accept Turkish mediation efforts. The latter course was chosen and resulted in “written guarantees” from Ukraine promising that the safe corridor or Ukrainian ports would not be used for attacks on Russian naval ships (BBC, November 2, 2022).

The war has put enormous pressure on global food markets, and there is no guarantee Russia will renew the export agreement in mid-November. It would, however, be in Moscow’s interests as the alternatives are not promising. Once Russia tries to enforce a blockade of the Black Sea corridor, it loses all its leverage. At that point, there would be no reason for Ukraine not to continue attacking the apparently vulnerable Russian Black Sea fleet. The move would also cause damage to the relationship with Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who has performed a valuable role as mediator between the Kremlin and the West. Food insecurity leads to political insecurity – Moscow stands to lose the quiet support it has in many parts of the developing world if food-laden freighters start going to the bottom of the Black Sea.

The Food Crisis

Among these developing nations is insurrection-torn Mali. Mali imports 14% of its food. In 2019, the top countries from which Mali imported food products included Brazil, South Africa, Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal and France. While neither Ukraine nor Russia figure largely in Mali’s food sources, global shortages in grain, cooking oil and other products affected by the conflict in Ukraine create competition for diminishing supplies, increased food prices and even civil insecurity.

Mali’s military, known for severe measures against civilians (torture, illegal detainment, summary execution) and for internal fighting while ignoring the terrorist threat, has lost respect in many areas of the country. Having failed to provide security in wide swathes of the nation, government security forces are being replaced by local, ethnically-based “self-defense” militias largely beyond any type of government control. Sometimes well-armed, these militias often attempt to resolve tribal disputes with soaring rates of violence. The worst of Mali’s internal ethnic conflicts is between the agricultural Dogon community and the pastoral Fulani (a.k.a. Fula, Peul, Fulbe). With a spiralling death-rate, the original disputes between farmers and herders over access to land and water have become secondary to the perceived need to meet extreme violence with greater violence.

The Dogon

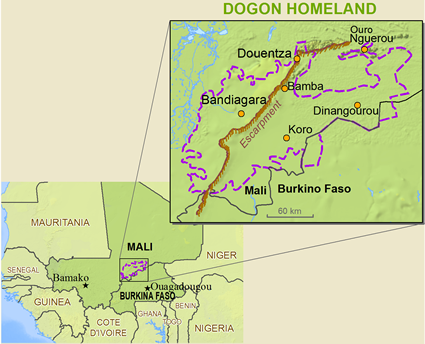

The Dogon homeland is found along the 93-mile long Bandiagara escarpment, slightly north of Mali’s border with Burkina Faso. The region’s unique geology and cliff-side architecture led to it being recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site in 1989. The Dogon arrived in the area sometime in the 14th or 15th century, displacing the Tellem (Dogon – “We found them”), who practiced a Stone-Age hunting culture. Most Dogon continue to practice a highly ritualized polytheistic religion, though the 20th century witnessed the growth of significant Christian and Muslim minorities. A centralized leadership does not exist, with each village governed by its own elected spiritual and political leader, the hogon.

The Dogon in Mali (Joshua Project)

The Dogon in Mali (Joshua Project)

The Dogon are best known to the outside world through their elaborate ritual masks and, unfortunately, a persistent pseudoscientific delusion that the Dogon, without any type of telescopic instruments, possess highly advanced astronomical knowledge. Though Afro-centrists have advanced the theory that the skin pigment melanin allowed the ancient Dogon to see minute details of incredibly distant star systems with the naked eye, the Dogon knowledge of astronomy was most likely gained in 1893 when a team of French astronomers stayed with the Dogon for five weeks. When French anthropologists recorded Dogon knowledge in the 1930s, they mistakenly included their limited astronomical knowledge as part of the Dogon belief system. In modern years, the “ancient astronaut” and New Age crowd consider Dogon astronomical knowledge as the result of early visitations to the Dogon by extraterrestrial fish-men from the Sirius star system. [1]

Dogon Cliff Dwellings in Bandiagara

Dogon Cliff Dwellings in Bandiagara

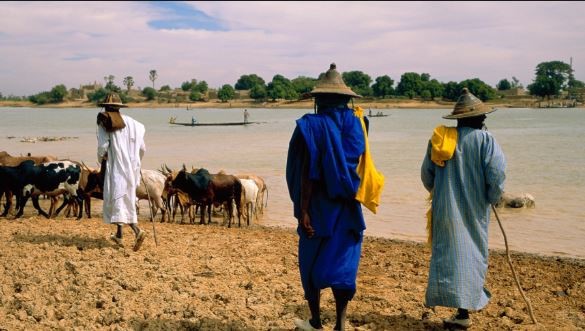

In reality, the Dogon practice sedentary agriculture, which has sometimes brought them into conflict over land rights and access to water with their semi-nomadic Muslim Fulani neighbors, whose culture and economy is built around raising cattle. Such disputes were customarily resolved by community elders who recognized the symbiotic relationship between herders and farmers. In recent years, however, traditional conflict resolution methods have begun to fail due to loss of farmlands to desertification, growing numbers of cattle, external provocation of the Fulani by Muslim extremists, an absence of government control and a proliferation of automatic weapons. The latter has helped replace negotiable and individual incidents of violence with large-scale massacres that have no apparent resolution for their victims other than retribution in kind.

Like their neighbors in Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire, the Dogon include a fraternity of traditional hunters known collectively as the “Dozo Ton” (Hunters’ Fraternity). Typically clothed in brown garments, the Dozo conduct secret rituals and initiations and wear amulets intended to make them bullet-proof.

Amidst growing insecurity in 2016, the Dogon Dozo formed a self-defense militia called the Dan Na Ambassagou (“Hunters who trust in God”). In recent years the Dozo hunters have added automatic weapons to their traditional arsenal of flintlocks, leading to charges from the Fulani that Mali’s deposed government was arming the hunters as a means of farming out the war against Islamist extremists. According to a Dan Na Ambassagou leader, the militia has indeed provided guides for patrols of the Forces Armées du Mali (FAMA – Armed Forces of Mali) (Reuters, April 19, 2019). Survivors of several massacres of Fulani civilians have identified the Dogon Dozo as the perpetrators.

Mamadou Goudienkilé, president of the Dan Na Ambassagou movement and a former captain in the Malian army, claims the hunters are not simply targeting Fulani:

The Fulani are our neighbours, we are ready to live with them. We are fighting the jihadists, not the Fulani. If the jihadist is Fulani, we fight him, if he is Dogon, we fight him too. But I repeat: this war is not between the Fulani and the Dogon… (Le Point [Paris], April 13, 2020).

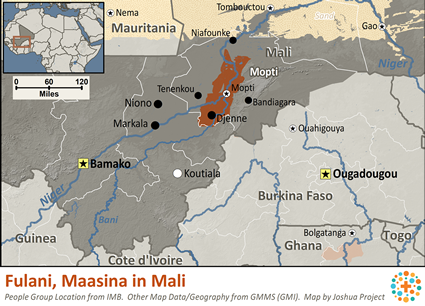

The Fulani

To counter the Dogon Dozo hunters, Mali’s Fulani attempted to consolidate their own local self-defense groups into the larger Alliance pour le Salut au Sahel (ASS – Alliance for the Salvation of the Sahel) in May 2018. The militia’s leader, who goes by the pseudonym “Bacar Sow,” maintained the Fulani are as much victims of the jihadists as any other Malian community, pointing as well to decades of government neglect fueling the intercommunal violence:

The areas where we operate have been abandoned since independence. In these areas, there is a lack of water, electricity, infrastructure and development. There are no schools, there are no roads, no health center. All that is necessary for the development of man is sorely lacking in us… Since [independence in] 1960, the various governments have done nothing and a total social disorder has taken hold (Monde Afrique, March 25, 2019).

The Dogon, Bambara and other ethnic groups believe the Fulani cooperate with regional jihadists, a belief reinforced by the emergence of the mostly Fulani Katiba Macina extremist group in 2015. Led by Fulani imam Amadou Koufa, a veteran of Iyad ag Ghali’s Ansar al-Din (Supporters of Religion), the group joined the al-Qaeda-connected Jama’a Nusrat al-Islam wa’l-Muslimin (Support Group for Islam and Muslims – JNIM) in 2017. In a November 2018 video, Koufa appealed for an ethno-religious Fulani insurrection in seven African countries (RFI, November 9, 2018). Koufa was declared dead by Malian authorities later that month following a French military operation, but re-emerged in a February 28, 2019 video mocking both the French and Malian security forces.

The Fulani are repeatedly targeted by the mostly Bambara Malian army, which often treats all Fulani as terrorists, Islamist extremists or supporters of the jihad groups that have spread their activities from Mali’s north to its central region since 2013. A degree of animosity between the Muslim Fulani and non-Fulani peoples of Mali (including other Muslims) dates back to the great theocratic Fulani kingdoms that dominated the region in the 19th century.

The Fulani are repeatedly targeted by the mostly Bambara Malian army, which often treats all Fulani as terrorists, Islamist extremists or supporters of the jihad groups that have spread their activities from Mali’s north to its central region since 2013. A degree of animosity between the Muslim Fulani and non-Fulani peoples of Mali (including other Muslims) dates back to the great theocratic Fulani kingdoms that dominated the region in the 19th century.

The jihadists, who have suffered serious losses in recent years, are reported to have recently begun pressing young men into their ranks, summary execution being the alternative to recruitment. Once absorbed into the ranks, each recruit is issued a weapon and a motorcycle (Le Soir de Bamako [Bamako], October 18, 2022).

In the last two years, JNIM jihadists, including Katiba Macina, have been in steady conflict with rival jihadists of the État islamique au Grand Sahara (EIGS – Islamic State of Greater Sahara) after some members of Katiba Macina defected to the Islamic State.

Fulani Herders on the Niger River, Mali (TVC News).

Fulani Herders on the Niger River, Mali (TVC News).

In an attempt to strengthen their position in the region two years ago, JNIM militants tried to mediate between the Dogon and Fulani communities. The point was to try and end clashes between the groups that made jihadist expansion difficult while severing Dogon ties to the state. These efforts were initially successful, allowing farmers and herders to operate in peace, but ultimately, they collapsed, marking a return to intercommunal violence and interruptions in the local food supply (Reuters, August 28, 2020).

Before his 2020 overthrow and subsequent death in January 2022, Malian president Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta sought to explain the growing hostilities between Fulani and Dogon:

The violence and cleavages we are witnessing are an outgrowth, a contagion of what has happened in the North [of Mali] over the past decade. As part of their expansionist and hegemonic project, jihadist terrorists have exploited the bankruptcies and weaknesses of the administrative network to insinuate and spread an exclusive speech of hatred, all under the guise of religion (Jeune Afrique, July 2, 2019).

Militia vs. Military

The militias all cite the same reason for their formation – the inability or unwillingness of government security forces to secure their communities from attacks and property theft, especially in the last four years. Malian security forces rarely make an appearance during the attacks, regardless of their proximity to the attack or its duration, citing shortages of men and equipment and even the difficulty of operating in the dark.

Illustrative of the military’s declining prestige was the reaction of Dogon villagers when a truck full of soldiers arrived in the town of Koro to arrest Marcelin Guenguéré, spokesman of the Dogon Dan Na Ambassagou militia and a suspect in violent attacks on the Fulani. Video shot by the militia showed the troops being driven away by chanting, rock-throwing locals and Dogon hunters. Ignoring the president’s order to dissolve the Dan Na Ambassagou, Guenguéré declared that any attempt to disarm the militia “could provoke a rebellion that will not be so easily contained” (Reuters, April 19, 2019). Mamoudou Goudienkilé, president of Dan Na Ambassagou, insisted that “Before disarming ourselves, we should already disarm the jihadists who are killing our people, stealing our cattle and burning our villages!” (RFI, March 10, 2021).

Youssouf Toloba (Malivox/Youtube)

Youssouf Toloba (Malivox/Youtube)

The movement’s military leader, Youssouf Toloba, pointed out the president could not dissolve the group as he “wasn’t the one who created it.” Toloba added that his movement had signed a cease-fire agreement in return for a government pledge to secure the Dogon homeland, “but then nothing was done…” (VOA, March 25, 2019). Toloba provided his interpretation of the role of the Dan Na Ambassagou to a French newspaper:

We do not accept being called bandits or militia on the understanding that, in general, the term “militia” has a negative, even pejorative connotation. We are not a militia, we are rather resistance fighters like those who, in France, during the Second World War, took up arms against the Germans who were the invaders (Le Point [Paris], April 3, 2021).

Toloba has repeatedly called for a combat alliance between FAMA and the hunters, claiming the latter possess invaluable intelligence regarding the position and the operations of the jihadists (Nouvel Horizon [Bamako], May 10, 2022).

Other Fulani have joined non-Islamist self-defense militias, such as the one led by Sékou Bolly, a Fulani businessman who formed a loose alliance with the pro-government, Tuareg-dominated Mouvement pour le salut de l’Azawad (MSA – Movement for the Salvation of Azawad) and absorbed former jihadists in his militia who passed through the Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (DDR) process. [2]

Cooperation between Guinguéré and Sékou Bolly in the interest of establishing peace angered elements in both the hunter and Fulani communities, who regarded it as a betrayal of their interests. In turn, Guinguéré and Bolly have both demanded that Youssouf Toloba submit to the state following accusations the militia leader has abandoned the mission of defending Dogon communities in favor of extortion and the looting of resources (Le Wagadu [Bamako], January 13, 2021).

Dan Na Ambassagou fighters clashed with JNIM militants (likely part of the Fulani-based Katiba Macina) last May. The katiba (battalion) had been pressuring local Dogon communities to join a government-sponsored attempt to create local non-aggression agreements with the jihadists (Nouvel Horizon [Bamako], May 16, 2022). Toloba opposed these “wacky peace deals” with jihadists:

Why would we cede our land to strangers? The goal of the jihadists is to subjugate us. To sign an agreement with them is to betray the Malian state, which is secular. These agreements entail the application on the ground of sharia, which we do not want (Le Point [Paris], April 3, 2021).

Massacres at Ogossogou and Moura

On March 23, one of the worst slaughters in modern Mali’s history occurred at the Fulani village of Ogossogou in the Mopti region of central Mali. Nearly 160 Fulani civilians perished in the brutal attack, allegedly carried out by the Dan Na Ambassagou. Many of the dead were hacked to death by machetes while others were burned alive in their homes. Typical of such attacks, all farm animals were either killed or carried away, leaving the survivors to starve without assistance.

Colonel M’Bah Ag Moussa (Malijet)

Colonel M’Bah Ag Moussa (Malijet)

The assault occurred one day after JNIM jihadists claimed responsibility for a March 17 attack on the FAMA garrison at Dioura (Mopti region) in which 23 soldiers were killed and a substantial quantity of arms and military gear seized by the assailants, who arrived by motorcycle and automobile. The JNIM statement (carried by its media arm, al-Zallaqa) said the attack was retribution for the government’s “heinous crimes” against the Fulani, but denied the Dioura attack was led, as claimed by the government, by a two-time FAMA deserter, Colonel M’Bah Ag Moussa “Abu Shari’a” (a.k.a. Bamoussa Diara). (Defense Post/AFP, March 18, 2019; Africa Times, March 24, 2019). [3]

Youssouf Toloba’s Dogon and Sékou Bolly’s Fulani militia had conducted successful mixed patrols in the region until the Ogossogou massacre. Bolly loudly accused Dan Na Ambassagou of responsibility for the attack, ending the possibility of further joint patrols. When Toloba was asked about a UN accusation of Dan Na Ambassagou responsibility, he asked: “Did the United Nations catch Dan Na Ambassagou attacking the village?” (Le Point [Paris], April 3, 2021).

Da Na Ambassagou spokesman Maracelin Guenguéré insists, improbably, that the Ogossogou massacre was in fact carried out by other Fulanis, not Dogon: “I can assure you of one thing, today everyone can have access to a hunter’s outfit. These are not hard to get outfits… There are Fulanis who are in conflict with other Fulanis. They manage to kill each other and pretend that it is the Dogons who killed them” (Le Point [Paris], June 20, 2019).

Less than a week after the Ogossogou affair, a March 27 FAMA/Russian raid on the Katiba Macina-held town of Moura was followed by five days of bloodletting, with over 300 civilians murdered after a brief firefight with a small group of 30 armed jihadists, most of whom escaped. The dead filled three mass graves they were forced to excavate first. The attackers indulged in days of rape and looting, as well as the destruction of motorcycles, commonly used by the jihadists. Using FAMA interpreters, the Russians separated Fulanis from other ethnic groups, explaining they needed to be killed as all Fulanis were supporters of jihad (Human Rights Watch, April 5, 2022).

Retaliation at Sobane Da

Retaliation for the Ogossogou massacre came on the night of June 9-10, when an attack on the Dogon village of Sobane Da was carried out by some 50 gunmen on motorcycles or pick-up trucks. Over eight hours the attackers, identified by the survivors as Fulanis, disembowelled many of their victims and burned women, children and the elderly alive inside their huts (France24.com, June 11, 2019; Le Monde [Paris], June 11, 2019; Le Point [Paris], June 20, 2019). At least 35 villagers were killed. Dogon leaders later claimed the Fulani militia of Sékou Bolly committed the atrocity in revenge for Ogossogou.

According to Da Na Ambassagou spokesman Marcelin Guenguéré:

The people who attacked us, those terrorists, those jihadists, I assure you that these are people we know, these are our Fulani neighbors who are with us on Dogon territory. I do not incriminate all the Fulani, but it is the Fulani who live with us who are at the origin of all this, they have their agenda (Le Point [Paris], June 20, 2019).

On June 18, 2022, the Katiba Macina slaughtered 132 civilians near Bankass, in the Mopti region of central Mali. On July 20, an assault by the militants on the town of Kargué was badly defeated by Dan Na Ambassagou fighters, who killed 53 of the attackers (Le Pays [Bamako], July 22, 2022). On July 23, the katiba attacked the Kati military base outside of Bamako, killing a soldier and demonstrating an unsuspected ability to reach right into the heart of Mali’s military structure.

There seems no end to the cycle of violence – Russian Wagner personnel and Malian troops were accused of massacring 13 civilians in the Fulani village of Guelledjé on October 30 (Africanews/AFP, November 1, 2022). Idrissa Sankaré, a leading official of the Tabital Pulaaku Mali (a civil Fulani umbrella group) recently warned a gathering of Fulani leaders: “Malians must understand that we are condemned to live together, to accept each other mutually to defend our homeland together, to avoid suspicion, amalgamation, hatred… not wanting to live in together is to want to disappear together” (Maliweb, August 31, 2022).

Forecast – The Shift to Moscow

Like a number of other African nations, Mali is now turning to Moscow for security assistance after French counter-terrorist forces withdrew in February. Mali has received an influx of fighters from the Russian Wagner network as well as Russian jet-fighters, mobile radar systems and transport and attack helicopters. Local pro-Russian activists organize demonstrations demanding a Russian presence in Mali -their funding comes from a Wagner-associated mining company with access to Malian gold deposits. Malian authorities, likely with encouragement from Russian disinformation specialists, claim French aircraft collect intelligence for the jihadists and deliver them shipments of arms. [4] Russians patrol the grounds of the presidential palace in Bamako; France’s President Macron has suggested the new military regime is looking to the Russians for protection rather than help in fighting terrorists.

The Black Sea transit agreement expires on November 19. Even if the shipping corridor remains open, the total amount of Ukrainian grain and other agricultural products shipped remains small, somewhere around one-tenth of what still awaits export. Some 77 empty freighters are off Ukraine’s ports, awaiting their loads of grain and sunflower oil.

Mali’s minister of the economy, Alousseini Sanou, visited Moscow in the first week of November. In an appearance on Malian state TV, Sanou announced Russia was sending aid to Mali in the form of 60,000 tonnes of petroleum products, 30,000 tonnes of fertilizer and 25,000 tonnes of wheat. The shipment was first discussed in an August phone call between Putin and Colonel Assimi Goïta but has yet to be confirmed by the Kremlin (Reuters, August 11, 2022; al-Jazeera, November 3, 2022; Agenzianova [Rome], November 3, 2022).

If the Russian supplies do materialize, it will provide some relief for Mali, but with jihadists shooting farmers in their fields it will not provide a long-term solution to the diminishing food supply and intercommunal violence, violence that the introduction of private Russian military contractors has only exacerbated. After a meeting with the Turkish defense minister on November 3, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg identified the cause of the growing food crisis being exploited by the jihadists for their own benefit:

The increased prices and the problems we have seen in the global food market are not caused by sanctions. It is caused by the war itself… It is the war of aggression that is undermining and threatening the supplies of food from Ukraine to the world market. The grain deal helps to reduce the effects, but the lasting solution will be to end the war and that’s Russia’s responsibility… [5]

Notes

- See, for example: Temple, Robert K.G: The Sirius Mystery: New scientific evidence of alien contact 5,000 years ago, (2nd ed), London, 1999 (1st ed. – 1976).

- Aurélien Tobie and Boukary Sangaré: The Impact of Armed Groups on the Populations of Central and Northern Mali: Necessary Adaptations of the Strategies for Re-establishing Peace, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), 2019, p. 10.

- Ag Moussa was a mixed Tuareg/Bambara considered close to JNIM leader Iyad ag Ghali. He received his military training in Libya and was a native of Kidal region in Mali’s north. Military commander of JNIM since 2017, Ag Moussa was killed in a carefully planned French attack in the Gao region on November 10, 2020. Sidi Mohamed ag Oukana, Ag Moussa’s half-brother, remains Iyad ag Ghali’s senior religious advisor. See “French Troops Kill JNIM Military Leader Colonel Bah Ag Moussa Diara: What are the implications?” AIS Militant Profile, November 20, 2020, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4689

- Last month, Malian Foreign Minister Abdoulaye Diop demanded an emergency session of the UN Security Council to address Malian allegations that France was providing weapons, ammunition and intelligence to jihadist groups (Le Témoin [Bamako], October 25, 2022).

- NATO Press Conference, Istanbul, November 3, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/opinions_208413.htm