Andrew McGregor

January 7, 2013

The Sudanese capital of Khartoum is currently the center of a web of intrigue involving an alleged coup attempt, bitter divisions in the Islamist movement, a mysterious airstrike on the capital by Israeli warplanes and what appears to be a possible shift in foreign policy that would involve greater military and diplomatic cooperation with the Iranian-led “Resistance Axis.”

Most worrisome for the ruling Islamist/military alliance led by President Omar al-Bashir is the alleged coup attempt, which reflects growing divisions within the ruling National Congress Party (NCP). Rather than being the work of outsiders to the power structure, the attempted coup appears to have been the work of a combination of members of the powerful National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS), Islamist officers of the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) and the Popular Defense Forces (PDF) and possibly a number of Islamist politicians and businessmen. With an ailing Bashir possibly ready to step down later this year after 24 years of rule, there is a growing tendency for political contenders to act peremptorily to secure their accession to power in a nation roiled by multiple rebellions and the economically devastating separation of South Sudan in 2011.

“Corruption and Deviance from the Islamic path”

National Congress Party officials disclosed that 13 individuals had been arrested in a November 21 NISS round-up on charges of planning the overthrow of the government, including some of the most powerful men in the country. Most of the detainees may be characterized as hardline Islamist military and intelligence officers who are said to oppose the “corruption and deviance from the Islamic path” of the current regime. The alleged plotters are charged with targeting “the stability of the state and some leaders of the state” (AFP, November 29). The suspects face repercussions ranging from a presidential pardon to death sentences, though the latter would certainly be seen as provocative by many within the Islamist power structure (al-Mashhad al-An [Khartoum], December 6, 2012).

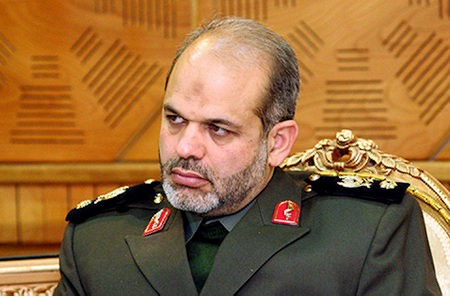

Nafi Ali Nafi

Nafi Ali Nafi

Among the suspects are:

- Former Presidential advisor and former NISS director Lieutenant General Salah Abdallah Abu Digin (a.k.a. Salah Gosh). Well known throughout Sudan, Salah Gosh was national intelligence director until he was sacked in 2009 following the failure of the Sudanese intelligence forces to discover and deter an attack by Darfur rebels on the national capital. He then served as a presidential advisor for security affairs for three years until losing that position in a 2011 power struggle with NCP vice-chairman Dr. Nafi Ali Nafi. Privately, Gosh’s family is reported to have claimed Nafi Ali Nafi is behind the charges against the former NISS director (Sudan Tribune, December 22, 2012). Following his surprise dismissal, Gosh went into business by opening a number of trading companies but was still reputed to be influential in regime circles. Gosh was taken to hospital with heart problems shortly after his arrest, where he underwent successful heart bypass surgery (AFP, November 29, 2012; al-Watan [Khartoum], December 2, 2012; Akhbar al-Yawm [Khartoum], December 6, 2012). Despite U.S. sanctions, Sudanese intelligence worked closely with its U.S. counterparts during Salah Gosh’s time as intelligence chief, with Gosh regarded as Sudan’s point man for contacts with the CIA. It was reported that Sudanese intelligence took a closer look into Gosh’s activities after noting he had gradually moved 25 members of his family to the United States earlier this year (al-Akhbar [Khartoum], November 24, 2012). Since his arrest, Gosh has had his immunity from prosecution revoked and his assets frozen by the Central Bank of Sudan.

Former NISS director Lieutenant General Salah Abdallah Abu Digin (a.k.a. Salah Gosh)

Former NISS director Lieutenant General Salah Abdallah Abu Digin (a.k.a. Salah Gosh)

- Brigadier General Muhammad Ibrahim Abd al-Jalil (a.k.a. Wad Ibrahim), a veteran of 12 years of fighting in the South Sudan and once considered the Amir of the “Mujahideen” movement in Sudan, dedicated to transforming the Sudanese civil war into a “jihad” against Christians and animists in the South. Known for his modest lifestyle and so far untainted by charges of corruption, Wad Ibrahim is reputed to be a popular figure in the Sudanese officer corps. He was in charge of the president’s security for seven years.

- NISS Major General Adel al-Tayib, a cousin of Wad Ibrahim (Sudan Tribune, November 22; al-Intibaha [Khartoum], November 29, 2012).

- Former commander of the Sudanese-Chadian Border Force Colonel Fath al-Rahim Abdallah Sulayman, who is alleged to be the go-between for Wad Ibrahim and Salah Gosh.

- Khalid Muhammad Mustafa, a former mujahideen commander operating in the Blue Nile region. Khalid is believed to be close to Wad Ibrahim.

- Businessman Mustafa Nur al-Dayim, who is alleged to have ties to Dr. Hassan al-Turabi’s Popular Congress Party (PCP) (al-Intibaha [Khartoum], November 29, 2012; December 6, 2012).

- Lieutenant Colonel Amin al-Zaki, a well-known Islamist and deputy director of the NISS in White Nile Province.

- Lieutenant Colonel Mustafa Mumtaz of the Signal Corps, based in White Nile province and thought to be an associate of Wad Ibrahim (al-Intibaha [Khartoum], November 29, 2012).

- Colonel Muhammad al-Zaki of the Armored Corps.

- Colonel Hassan Abd al-Rahim of the Armored Corps. Abd al-Rahim is alleged to have provided contacts between the plotters and the Darfur-based Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) (al-Intibaha [Khartoum], December 6, 2012).

- Dr. Ghazi Salah al-Din – Head of the NCP bloc in parliament and formerly a close advisor to the president, entrusted with important files such as the Darfur issue. Ghazi Salah al-Din is a leader of the reform movement within the NCP that has mobilized behind the issues of corruption and economic deterioration (al-Akhbar [Khartoum], November 24, 2012).

- Major General Musa al-Amin (al-Ahram al-Yawm [Khartoum], December 4, 2012).

- General Abd al-Mula Musa Muhammad Musa – The retired general and commissioner of the White Nile State was arrested on December 3 after his name emerged during interrogation of the other suspects (al-Ahram al-Yawm [Khartoum], December 4, 2012; Sudan Tribune, December 5, 2012).

Two prominent politicians have been implicated in the plot, though solid evidence has not been presented and both men remain free for the moment. Both men have a history of antagonism to the regime and could be considered to fall into the “usual suspects” category whenever Khartoum is faced with political disturbances:

- Dr. Hassan al-Turabi: The leader of the Islamist Popular Congress Party and former leader of the National Islamic Front (NIF). Though Turabi was not specifically named in connection to the coup, presidential advisor Nafi Ali Nafi’s reference to the plotters receiving assistance from “Islamists who have personal ambitions” was widely thought to be a reference to al-Turabi (Sudan Tribune, December 2, 2012). Dr. Hassan Abdallah al-Turabi was the first Secretary-General of the Islamic Movement, but underwent a split with the faction led by President Omar al-Bashir in 1998, leading to the formation of al-Turabi’s Islamist opposition party, the Popular Congress Party (PCP).

- Sadiq al-Mahdi, a former two-time Prime Minister of Sudan (1966-1967, 1986-1989) was overthrown by the military/Islamist alliance of Colonel Omar al-Bashir and Dr. Hassan al-Turabi in 1989. Sadiq is the great-grandson of Muhammad Ahmad al-Mahdi, the 19th century Sufi leader who overthrew Egyptian rule of the Sudan in 1885. Sadiq is the Imam of the Ansar Sufi movement and leader of its political wing, the Umma Party (a.k.a National Umma Party – NUP).

After meeting with the Sudanese press during a visit to Cairo, al-Mahdi was initially quoted as saying Salah Gosh had met with him over dinner to ask the Umma Party leader to head the post-coup regime, though al-Mahdi later claimed he had been quoted out of context (al-Sudani [Khartoum], December 4, 2012; al-Qarar [Khartoum], December 5, 2012; Sudan Vision, December 31, 2012). Presidential Assistant Nafi Ali Nafi asked: “Is it logical that Sadiq al-Mahdi [would] disclose what went on between him and Gosh in the past without meaning it?” (Sudan Tribune, December 15, 2012).

Al-Mahdi has also been described as having extensive contacts with the rebel Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF) coalition by media sources unfriendly to the NUP. Presidential advisor Nafi Ali Nafi has said he is “confident that the Umma party knew the zero hour [of the coup attempt]” (Sudan Tribune, September 22, 2012). NUP leaders and members of al-Mahdi’s Ansar religious movement have warned against attempts to implicate al-Mahdi in the alleged coup (Sudan Tribune. December 3, 2012; Akhbar Alyoum [Khartoum], December 4, 2012). A recent sermon by the leader of the Ansar council decried the presence of foreign UN and AU troops in the country, the absence of democracy and the alleged usurpation of the nation’s resources by the ruling circle (al-Sudani [Khartoum], December 22, 2012).

While the regime has attempted to implicate the opposition, the episode instead suggests the military/Islamist coalition that has ruled Sudan since 1989 is experiencing another split as the coalition’s strongman, Bashir, begins to show signs of physical weakness that could imperil his grip on the regime. Bashir has also suffered political blows in recent years by being indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Court (ICC) and failing to triumph in the battle against Southern secession.

Jockeying for Political Supremacy

Within the so-called “loyalist” faction of the NCP there are several possible successors to President-Field Marshal Bashir, who is expected to resign later this year or by 2015 at the latest:

- Dr. Nafi Ali Nafi – NCP vice-chairman, former major-general and current presidential advisor. Nafi is one of the most powerful men in Khartoum and is regarded as being extremely close to the president. As a former Iranian-trained chief of military intelligence, Nafi was entrusted with overseeing controversial security operations in Darfur and South Kordofan that have been described by observers as crimes against humanity. Nafi emerged as the victor in a power struggle with Salah Gosh when the latter was dismissed as NISS director. Nafi is seen by some as al-Bashir’s bulwark against the ambitions of First Vice President Ali Uthman Muhammad Taha. Nafi and al-Bashir are both members of the riverine Ja’aliyin tribe.

- First Vice President Ali Uthman Muhammad Taha – A leading member of Sudan’s Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan) and a former Turabi loyalist who abandoned his mentor when the latter fell out with Bashir. Taha was rewarded with the vice-presidency and often acts as the public face of the government while building a powerful constituency as the deputy chairman of the NCP. Taha is a lawyer and judge by profession and a member of the Shaiqiya, one of the three riverine Arab tribes (Shaiqiya, Ja’aliyin and Danagla) that have monopolized power in Sudan since independence. Taha is deeply implicated in unleashing the Janjaweed forces of Musa Hilal in Darfur. A two-time Amir of the Sudan Islamic Movement (SIM), Taha is an NCP insider regarded as a frontrunner and will likely have the backing of the SIM’s new leadership in any run at the presidency.

- Speaker of the National Assembly Ahmad Ibrahim al-Tahir – A leading hardline member of the NCP who has described the late Osama bin Laden as “a holy warrior” and describes the separation of South Sudan as an “international conspiracy” (al-Ra’y al-Aam [Khartoum], June 26, 2011; Sudan Tribune, May 3, 2011).

- Lieutenant General Bakri Hassan Salih – Minister of Presidential Affairs and former Minister of Defense, General Bakri is deeply implicated in the abuses committed by pro-government militias and government security forces in Darfur. He has been close to al-Bashir ever since he played a crucial role in the 1989 coup that brought al-Bashir to power.

Divisions in the Sudanese Islamic Movement

The growing differences between factions of the ruling National Congress Party (NCP) began to erupt in January with the release of a memo calling for urgent reforms and an end to institutionalized corruption. The memo was signed by a thousand party members and associates (Sudan Tribune, January 11, 2012).

Splits in Sudan’s Islamist movement between those favoring the political status quo and those seeking political reform emerged at the 8th General Conference of the Sudanese Islamic Movement (SIM) in November. With the resignation of Sudanese vice-president Ali Osman Muhammad Taha as SIM chairman, a struggle emerged for control of the movement. The conference quickly deteriorated into a confrontation between Bashir regime loyalists and those seeking substantial reforms within the failing Sudanese administration. Among those groups in the SIM calling for reform was al-Saihun (“the Travelers”), an NCP-associated faction based upon a core of veteran military officers and paramilitary jihadists embittered by the loss of South Sudan after a long and bloody civil war. Some NCP loyalists maintain that al-Saihun is a front for members of the PCP (Alwan [Khartoum], November 29, 2012). Al- Saihun and PCP leader Hassan al-Turabi backed NCP parliamentary leader Ghazi Salah al-Din in an unsuccessful bid for the leadership of the SIM. However, NCP loyalists assumed control of the movement with the election of economist al-Zubayr Ahmad al-Hassan as the new secretary-general of the SIM after Ghazi withdrew from the contest. Ghazi was accused a short time later of being one of the alleged coup plotters. Under al-Zubayr’s leadership, many Islamists contend the SIM has now been reduced from an advisory body to the NCP to a movement whose views will be dictated by the regime. SIM reformers were ultimately unable to push through their demands that the movement be separated from the NCP.

After the conference, al-Saihun issued a statement calling for the dismissal of Minister of Defense Abd al-Rahim Muhammad Hussein. The reformers cited the minister’s disputes with senior army officers (some ending in dismissals), failure to respond to alleged Israeli attacks on Sudan and an inability to provide Sudanese troops and paramilitaries with the means to end rebellions in Darfur, South Kordofan and Blue Nile Province. The statement followed an earlier appeal in January, 2012 by 700 officers of the Sudan Armed Forces calling for an end to corruption in the arms procurement process, citing as an example the purchase of over 100 defective Ukrainian tanks in 2010 (Sudan Tribune, January 20, 2012). The officers also called for a greater degree of separation between the NCP and the Army command structure.

Motivations for Overthrowing the Bashir Regime

Speculation is rife in Khartoum over the motivation of the alleged putschists, with some suggesting the move was meant to preempt other attempts to seize power (a common justification for coup attempts in the Sudan). Speculation on the future of the regime has been fuelled by rumors that the president may be terminally ill. Al-Bashir has had two tumor-related surgeries on his throat in Qatar and Saudi Arabia since August, 2012 despite international sanctions against his travel connected to an ICC indictment for war crimes (BBC, November 30, 2012; Sudan Tribune, December 22, 2012).

There is also the possibility that the alleged plotters represented an Islamist faction within the military that felt that Khartoum’s ongoing military campaigns against various rebel movements were suffering from government corruption and the policies of Defense Minister Abd al-Rahim Muhammad Hussein. Besides the seemingly intractable conflict in Darfur, fighting has again flared up along the border of the South Sudanese state of Northern Bahr al-Ghazal (Sudan Tribune, December 10, 2012). Khartoum maintains that Juba continues to command and control troops of the SPLA-Northern Command now fighting the NCP regime in Sudan’s Blue Nile and Southern Kordofan provinces.

A Khartoum daily considered close to the Bashir regime provided details of the videotaped confessions presented by NISS director Muhammad Atta and Dr. Nafi Ali Nafi to a select group (al-Intibaha [Khartoum], December 6, 2012). According to the report, Wad Ibrahim and other coup plotters confessed to organizing the coup in cooperation with the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM), a Darfur-based rebel movement that came close to seizing the capital and deposing Bashir in 2008 and has remained a regime bogeyman ever since. [1] JEM’s participation was made conditional on the deportation to Europe for trial of the “List of 51,” a UN-generated sealed list of 51 Sudanese citizens suspected of war crimes in Darfur that was handed to the ICC in 2005. By mutual consent the coup would take place while Bashir was out of the country for medical treatment in recognition of the popularity of the president in some quarters and the difficulty of ultimately deporting Bashir to face his own ICC indictment. The detainees described Wad Ibrahim rather than Salah Gosh as the intended leader of a 15-member post-coup command council. Salah Gosh’s confession was not shown, raising questions as to whether the former intelligence director has in fact made a confession.

The videotaped confessions apparently included that of a “sorcerer” said to have been engaged by one of the generals involved in the plot to cast an immobilizing spell over certain regime figures. Pressed as to why he did not report the incident, the “sorcerer” claimed a dream revealed the coup would be unsuccessful, so he felt no further action was necessary.

NISS Director Lieutenant General Muhammad Atta al-Mawla

NISS Director Lieutenant General Muhammad Atta al-Mawla

Dealing with the “Traitors”

Having rounded up the coup suspects, the regime is now divided as to how to deal with them, a new dispute that is proving as divisive as any of the others facing the regime. The Director of the powerful National Intelligence and Security Services (NISS), Lieutenant General Muhammad Atta al-Mawla, described the plotters as “traitors” who had even drafted a proclamation announcing themselves as “counter-revolutionaries” who intended to supersede the “Salvation Revolution” of 1989. Al-Atta has pledged that the suspects will face justice without leniency (Sudan Tribune, December 5, 2012; Sudan Vision, December 7, 2012). Vice-President Taha says that the suspects will be prosecuted without special treatment: “We have no double standards… the way with us is working within the ranks, not treachery and treason and destabilizing the ranks” (Sudan Tribune, December 2, 2012). Presidential advisor Nafi Ali Nafi has been especially vocal in his demands that the suspects face trial, saying some of them had already been detained on similar charges in the past. This time, according to Nafi, there is ample evidence to mount a full prosecution (Sudan Tribune, December 22, 2012). A group of Khartoum lawyers led by government critic Nabil Adib has pledged to form a committee to defend the suspects while some NCP members have warned that action against the alleged plotters would be “costly” (Sudan Tribune, November 24, 2012; November 26, 2012).

On the other hand, prosecuting the still influential suspects could tear the ruling NCP apart at a time it can ill afford disunity in the ranks. According to the Sudan Tribune, an al-Saihun Facebook page claimed NCP parliamentarians organized a candid meeting between al-Bashir and the leading detainees on December 19 that ended with “hugging and tears,” though this could not be verified (Sudan Tribune, December 22, 2012). Bashir has been placed in a difficult position as prosecutions would likely generate new attempts to depose him. It might well be to the ailing president’s benefit to offer a grand gesture of forgiveness, with the quiet promise that further such dissent in the NCP will not be endured with magnanimity. However, with the prospect that Bashir might be president for only a short time longer, other ranking figures in the regime such as Taha and Nafi may see a purge as a means of reshaping the NCP going into the post-Bashir era.

Meanwhile, the streets of Khartoum have been the scene of massive and occasionally violent student demonstrations in recent weeks. The protesters, who call for the overthrow of the regime, initially flooded into the streets following the apparent murder of four students from Darfur by NCP members on December 7 (Sudan Tribune, December 10, 2012; Al-Sahafah [Khartoum], December 9, 2012).

The net continues to be cast wider and wider in the aftermath of the initial interrogations with the arrests of dozens of Saihun members as well as two “Islamist” media members, one a cameraman for al-Jazeera, the other an employee of the al-Fida Media Center, which used to produce videos promoting the jihad in South Sudan (Sudan Tribune, December 5, 2012).

The fallout from the alleged coup attempt has even reached various research centers, cultural centers and NGO’s active in Khartoum that are now alleged to be engaged in actions “prejudicial to national security” financed by foreign sources. Prominent among these are institutions receiving funds from the American National Endowment for Democracy, whose financing originates with the U.S. State Department The pro-government newspaper Akhir Lahzah reported in its Sunday’s edition that the authorities would launch a broad campaign against a number of “research centers, and those labeled cultural centers” (Akhir Lahzah [Khartoum], December 22, 2012; Sudan Tribune, December 29, 2012; Reuters, December 31, 2012). Dr. Nafi recently criticized American NGOs for their alleged contacts with rebel forces in Sudan, claiming that three American Jewish organizations had held meetings with the Sudan Revolutionary Front (SRF) to identify ways in which they could help the rebels overthrow the Khartoum government (Citizen [Khartoum], December 23, 2012).

A statement from al-Mahdi’s religious followers, al-Ansar, saw a more nefarious intent behind the security crackdown: “We doubt there was a coup attempt to begin with, and we believe it was an attempt to liquidate rivals and a move aimed at pre-empting dissent from the disgruntled youth of the Islamist movement” (Sudan Tribune, December 4, 2012). The post-coup crackdown seems to have had little success in restraining the growing number of calls for political reform and changes to the leadership. Al-Turabi’s PCP called for the president to step down, citing the government’s claim that Sadiq al-Mahdi and the National Umma Party were behind the coup attempt as “the last card” of a desperate regime (The Citizen [Khartoum], December 4, 2012).

The regime has also been embarrassed by the late December release on jihadi websites of video footage of the June 2010 escape by tunnel from Sudan’s most secure prison of four Islamist militants sentenced to death for the 2008 murder of a U.S. Agency for International Development official and his Sudanese driver (GIMF/al-Hijratain Media, Ansar1.info, December 28, 2012). [2] Apparently inspired by the similar escape of al-Qaeda militants from a Yemeni prison in February 2006, the chained convicts were apparently able to dig a 38 meter tunnel to freedom without interference from prison staff. [3]

Economic pressures in the wake of South Sudan’s separation are fueling growing discontent with the Khartoum government. Oil revenues have declined steeply, inflation is at over 40%, food supplies are soaring in price, professionals are fleeing the country and currency reserves are drying up. Khartoum continues to devote much of its spending to the repression of various uprisings in parts of the country.

Iranian Ships in Port Sudan

In the early hours of October 24, 2012, the Yarmuk small-arms factory in a southern suburb of Khartoum was attacked by Israeli fighter jets in what appeared to be a relatively risk-free practice run for an Israeli airstrike on Iranian targets. Israel has justified previous attacks on Eastern Sudan by claiming Iran ships arms through Sudan to Gaza, though even a basic knowledge of the distances involved, the exposed, waterless terrain and the fact that such overland shipments would require bypassing tight Egyptian border controls before crossing through several restricted military zones on the Egyptian Red Sea coast suggest that such claims have no basis in reality. [4] There are now claims from Israel that the Yarmuk arms factory was controlled by Iranian Revolutionary Guards and was engaged in producing arms for Hamas that were then shipped by the improbable overland route through Egypt to Gaza. Though new Egyptian president has adopted a more supportive stance towards Gaza than his predecessor, the overland arms route is alleged to have existed through several years of the Mubarak regime, which had no interest in arming the Gaza militants.

In the aftermath of the Yarmuk attack, the Sudanese Foreign Ministry said production at the factory had no connection to Iran, describing Israel as “an outlaw state… trying its best to pass fabricated information through different sources that have a link with Israel” (AFP, November 27, 2012; al-Arabiya/AFP, October 30, 2012). Opposition parties pointed out that the ease with which the Israelis were able to strike the capital confirmed Sudan’s military capacity was dedicated to the suppression of opposition movements rather than the defense of the nation (Sudan Tribune, October 30, 2012).

In light of the Israeli accusations, a visit to Port Sudan on October 28 by Iran’s “22nd Fleet” generated further speculation over the nature of relations between Tehran and Khartoum. Consisting of the supply ship Kharg (with three antiquated Sea King helicopters) and the Admiral Naghdi corvette (launched in 1964), the 22nd Fleet docked in Port Sudan after carrying out anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and the Mandab Strait. After three days in port the Iranian ships left on October 31 (Suna Online [Khartoum], October 31, 2012; Mehr News Agency [Tehran], December 9). Though uneventful, the visit was heavily criticized in the Saudi Arabian media as a threat to regional security and a danger to Sudan’s relations with Gulf countries. The Iranian ambassador to Khartoum rejected assertions from Tel Aviv that the mission of the Iranian ships was to offload containers of weapons intended for Hamas, pointing out that the ships were open to the public on all three days of their visit to Port Sudan (al-Watan [Khartoum], November 1, 2012).

Sudanese Foreign Minister Ali Karti, who has opposed greater cooperation with Iran on the grounds it would come at the expense of good relations with Arab Gulf countries, later revealed that his recommendation to reject a visit by Iranian ships in February, 2012 was accepted and acted on by the government, but the attack on the Yarmuk defense factory appeared to have produced a dramatic reversal in this policy (Sudan Tribune, November 27, 2012).

A second Iranian visit to Port Sudan came from the 23rd Fleet on December 8, though Sudanese officials maintained the visit was pre-planned and routine. The detachment included the supply ship Bushehr and the guided missile frigate Jamaran, the domestically-built pride of the Iranian Navy (though described inaccurately by Iran as a destroyer). Sudanese naval commander Abdallah Matari took the occasion to urge expanded Iranian-Sudanese military cooperation (Fars News Agency [Tehran], December 8, 2012).

The Sudanese Foreign Ministry insisted the visit was pre-planned and not intended as a reaction to the Israeli airstrike on Khartoum, though some Sudanese questioned the wisdom of allowing a second Iranian naval visit so shortly after the controversy generated by the first visit (Sudan Tribune, December 5, 2012; al-Ayam [Khartoum], December 10, 2012). Foreign Minister Ali Ahmad Karti confirmed divisions within the regime over Khartoum’s apparently growing relations with Iran when he revealed he had not been informed of the arrival of the two Iranian warships, saying he would have opposed the visit if he had been aware of it (al-Sudani [Khartoum], November 4, 2012; Sudan Tribune, November 4; The Citizen [Khartoum], November 5, 2012).

Since 2008, the Iranian Navy has been expanding its presence in the region through anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden, deployments to the Indian Ocean and the dispatch of two ships through the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean in February 2011. Taking his inspiration from remarks made by the Supreme Leader of Iran, Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the commander of the Iranian Navy, Rear-Admiral Habibollah Sayyari, has described the role of a “Strategic Navy” in securing Iranian waters, protecting Iranian shipping in international waters and projecting influence abroad (Vision of the Islamic Republic of Iran Network 1, November 29, 2012). Sayyari has emphasized Iran’s growing regional importance, noting that the Islamic Republic was now “a decision-maker in South Asia” that has reached a point where “no world power can ignore its influence in the region” (Fars News Agency [Tehran], December 12, 2012). Admiral Sayyari has elsewhere responded to alarmist news reports of the Iranian Navy’s activities by insisting that access to international waters belongs to all the people of the globe (IRNA, December 3, 2012). According to a major pan-Arab daily, Tehran offered Khartoum an alliance designed to “protect the Red Sea,” but Foreign Minister Ali Karti denied any knowledge of such a proposal (al-Hayat, November 2, 2012; Sudan Tribune, December 13, 2012). Karti is alleged to have opposed the alliance at a heated meeting of the NCP’s foreign relations committee.

Nevertheless, in defending the two visits by Iranian warships as “routine,” Karti claimed that American warships had made a similar stop in Port Sudan in November (Sudan Tribune, December 5, 2012). However, the Foreign Minister’s claim was challenged by U.S. Navy spokesmen, who insisted they “didn’t have any record” of American ships visiting the Sudan in November (Sudan Tribune, December 6, 2012).

A spokesman for the Darfur-based rebel Justice and Equality Movement (always eager to embarrass the regime) claimed that Khartoum and Sudan had discussed a deal to build an Iranian naval base, a base that some Israeli journalists fancifully maintain already exists in Sudan, allegedly employing hundreds of Iranian Revolutionary Guards offloading arms shipments for Hamas from Iranian cargo ships with to Iranian-run warehouses (Hurriyat [Khartoum], December 11, 2012; al-Rakoba [Khartoum], December 9, 2012, December 11, 2012; Yedi’ot Aharonot [Tel Aviv], October 25, 2012). The alleged Revolutionary Guards’ base in Port Sudan presumably cooperates with other phantom Iranian naval bases claimed to be in Eritrea. [5] Following the allegations, Sudanese foreign ministry undersecretary Rahmatallah Uthman asserted that Khartoum has a policy of not allowing foreign military bases on its soil, adding that Iran was “no exception” (The Citizen [Khartoum], December 10, 2012).

Israeli businessman are engaged in establishing an economic base in newly independent South Sudan, another point of contention with Khartoum, which has no desire to see Israeli influence grow in a neighboring nation, particularly one still as closely tied to (north) Sudan as South Sudan. Israel has a long but covert relationship with South Sudan, having begun providing military training to South Sudanese insurgents shortly after the nation gained independence in 1956.

Conclusion

If the alleged coup is grounded in fact, it would not be the first attempt to overthrow al-Bashir in the 24 year history of his regime and possibly not the last. It is the first, however, to be mounted by figures so close to the president and until now considered to be among the pillars of the regime. Democracy has never quite taken hold in Sudanese society, which remains afflicted with a tendency for certain individuals to decide it is they alone who have the answer to Sudan’s complex problems. The nation is in dire need of financial assistance but recent efforts to obtain financial aid from Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states have been unsuccessful. Iran is also suffering financially from economic sanctions against it, but a demonstration by Khartoum that it is considering closer ties to the Islamic state (such as hosting Iranian warships) may be one way of putting pressure on the Sunni states of the Gulf to reconsider their position. Khartoum is also in need of military assistance, having blown its chance to make significant upgrades to its military by indulging in a corrupt procurement process. China once seemed a promising partner in this regard, but the separation of the South Sudan now means that Beijing must maintain cordial ties with both north and south Sudan to ensure the continued flow of oil from Chinese owned wells in the south to the export terminal in the north. The Iranian dalliance is a dangerous gambit, however, as it poses both internal and external risks that may be greater than the possible benefits from a closer alliance with the Islamic state.

After 24 years of Islamist/military rule in Khartoum, the secular and non-Islamist opposition has been effectively marginalized, but emerging divisions within the Islamist camp will make it more difficult for the regime to resist the armed groups that threaten to tear the remaining state apart. A divided security structure also presents opportunities for Salafist-Jihadist cells (such as the one dismantled in Dinder National Park in December) to exploit the situation to their advantage. For the moment, the likelihood of a democratic succession in the Sudan appears increasingly remote

Andrew McGregor is the Director of Aberfoyle International Security, a Toronto-based agency specializing in security issues in the Islamic world.

Notes

1. For the raid on Omdurman, see Andrew McGregor, “Darfur’s JEM Rebels Bring the War to Khartoum,” Terrorism Monitor, May 15, 2008) http://www.jamestown.org/terrorism/news/article.php?articleid=2374172 and Andrew McGregor, “Traitors or POWs? Khartoum Sentences JEM Rebels to Death,” Terrorism Focus, August 6, 2008, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/gta/single/?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=5105&tx_ttnews[backPid]=246&no_cache=1

2. For the trial of the assassins, see Andrew McGregor, “Alleged Assassins of U.S. Diplomat Claim Khartoum Regime Incites People to Jihad,” Terrorism Focus, February 6, 2009, http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=34508

3. For the “Great Escape” in Yemen, see Andrew McGregor, “Al-Qaeda’s Great Escape in Yemen,” Terrorism Focus 3(5), February 7, 2006, http://jamestown.org/terrorism/news/article.php?articleid=2369888 and Andrew McGregor, “Yemen Convicts PSO Members Involved in February’s Great Escape,” Terrorism Focus 3(29), July 25, 2006, http://www.jamestown.org/single/?no_cache=1&tx_ttnews[tt_news]=847

4. See Andrew McGregor, “Strange Days on the Red Sea Coast: A New Theater for the Iran-Israel Conflict?” Terrorism Monitor 7(8), April 3, 2009 http://www.jamestown.org/programs/gta/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=34807&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=412&no_cache=1

5. For Eritrean reaction to such claims, see “Eritrea: Phantom Israeli and Iranian Military Bases,” Eritrean Centre for Strategic Studies, December 27, 2012, http://www.capitaleritrea.com/eritrea-phantom-israeli-and-iranian-military-bases/

Sudanese Troops in Yemen (AFP)

Sudanese Troops in Yemen (AFP) Sudanese Foreign Minister ‘Ali al-Sadiq ‘Ali (Osman Bakır – Anadolu Agency)

Sudanese Foreign Minister ‘Ali al-Sadiq ‘Ali (Osman Bakır – Anadolu Agency) Wad al-Bashir Bridge, Omdurman (Sudan Tribune)

Wad al-Bashir Bridge, Omdurman (Sudan Tribune) Sudanese Zagil-3 Drone – variant of the Iranian Ababil-3 (Skyscrapercity.com)

Sudanese Zagil-3 Drone – variant of the Iranian Ababil-3 (Skyscrapercity.com)