Andrew McGregor

September 27, 2012

Let’s begin with the assumption that Israel can overcome the logistical and political hurdles involved in mounting an attack on Iran’s nuclear development facilities, either unilaterally or in cooperation with the United States. Unlike earlier strikes on Syrian and Iraqi nuclear facilities, Iran will certainly retaliate for any attack on its soil. Given that both Israel and the United States, individually or in combination, could easily subdue the armed forces available to the Islamic Republic, what forms could Iranian retaliation take?

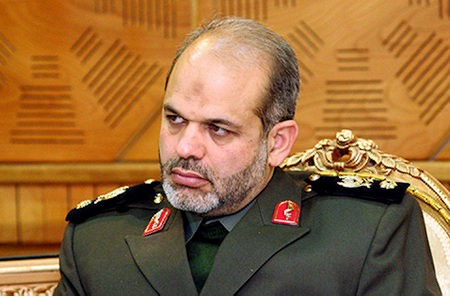

Iranian Defense Minister Brigadier General Ahmad Vahidi

Iranian Defense Minister Brigadier General Ahmad Vahidi

Rather than play the victim in its dispute with Israel, Iran has taken an aggressive tone in its response to threats of a military strike. On September 19 Iranian Defense Minister Brigadier General Ahmad Vahidi suggested that Israel was trying to cover up domestic problems by pursuing the rhetoric of war, adding that Iran is “able to wipe the [Israeli] regime off the scene” with its defensive capabilities (IRNA September 19; Fars News Agency, September 20). Vahidi and other Iranian leaders have been taking advantage of the annual “Week of Sacred Defense” commemoration of the Islamic Republic’s war with Iraq in the 1980s to remind interested parties of Iran’s successful eight year defense against the U.S. supported Iraqi regime of Saddam Hussein (Trend.az, September 22). However, such rhetoric is common from Iranian sources; the question remains as to whether Iran can back up its threats of massive retaliation.

The Missile Response

With a direct land-based retaliatory attack on Israel rendered impossible by geography and military considerations, Iran’s best chance for a direct blow to Israel lies in the possibility of Iranian long-range ballistic missiles penetrating Israel’s Arrow anti-ballistic-missile system and the much-heralded Iron Dome missile defense system. While the latter system has proved effective, its main weakness is its expense and inability to bring down more than a percentage of a mass missile barrage. Bringing down a cheap homemade rocket from Gaza can cost far more than the potential damage the rocket could inflict. Potential opponents of Israel such as Hezbollah now possess enhanced missile capabilities that make strikes on Tel Aviv and other urban centers in Israel a genuine possibility. A barrage of cheaper or smaller rockets from several directions at once might sufficiently tax Israel’s air defense systems to allow an Iranian ballistic missile with a conventional or non-conventional warhead to penetrate Israeli defense systems.

Besides the surface-to-surface Sejjil missiles and medium-range Shahab-3 ballistic missile with a range of up to 2,000 km, Iran has recently deployed upgraded versions of its twenty-year-old Zelzal rockets, which have a range of 300 km. To prepare for possible missile attacks on Israel a joint U.S.-Israeli missile defense exercise is expected to be held later this fall after the operation was delayed earlier this year (Financial Times, September 17). Militants based in Hamas-ruled Gaza, Israel’s weakest opponent, continue to fire missiles across the Israeli border despite scores of air raids, assassinations and even a 2009 deterrent raid that killed upwards of 1300 people.

According to Commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Major-General Muhammad Ali Aziz Jaafari, the U.S. military presence in the region will actually work against them as it brings U.S. military targets within range of Iranian counter-strikes (Tehran Times, September 16). General Jaafari has revealed that Iran does not believe Israel will succeed in persuading the United States to join in an attack on Iran but will nevertheless hold the United States responsible for any strike on its nuclear or military facilities (al-Sharq al-Awsat, September 21). Jaafari also remains confident of Iran’s ability to carry out effective missile strikes on Israel: “I think nothing will remain of Israel (should it attack Iran). Given Israel’s small land area and its vulnerability to a massive volume of Iran’s missiles, I don’t think any spot in Israel will remain safe” (Fars News Agency, September 16).

Iranian Air Defense

Iran’s ancient assembly of obsolete Soviet and American-built warplanes would be quick work for modern Israeli or American aircraft and would therefore be unlikely to be deployed in a conflict with these nations. However, if Israel were to conduct a unilateral attack, their aircraft would experience moments of vulnerability during the mid-air refueling required to get their aircraft to Iranian targets and back. Israel has conducted air exercises designed to counter such threats.

Iran’s R’ad Air Defense System

Iran’s R’ad Air Defense System

After the recent “successful testing” of Iran’s Ra’d air defense system, IRGC Brigadier General Amir Ali Hajizadeh said the system “has been manufactured with the aim of confronting [hostile] U.S. aircraft and can hit targets at a distance of 50 kilometers and at an altitude of 75,000 feet (22,860 meters)” (Tehran Times, September 24). The Iranian-built Ra’d system has not been used in a combat situation and will be subject to countermeasures available to Israeli or American aircraft, but unlike Qaddafi, Iran’s military and political leaders are not likely to hesitate to give the order to fire on foreign aircraft in Iranian airspace.

Asymmetric Responses

Attacks on Israeli facilities, institutions or individuals around the world by the IRGC, Iranian sympathizers or even other elements taking advantage of the situation to press their own political agendas would threaten to spread a potential conflict far beyond the Middle East. A covert war between Israel and Iran is already underway and can be easily intensified in the event of open conflict. This represents an open-ended threat that cannot be dealt with simply through the application of overwhelming air-power or incursions by land forces.

In the event of an attack on Iran, Iranian sympathizers and government agents will agitate public opinion in Muslim capitals around the world, fueling international condemnation of Iran’s attackers through violent demonstrations and attacks on Israeli and American institutions. Should such attacks turn bloody through the efforts of security agencies to restore order these disturbances could take on a life of their own, creating security issues and diplomatic crises that would sap public will to pursue a war or create internal political dissent. Recent anti-American demonstrations in the Middle East have demonstrated that regional governments may lack the will or the ability to restrain an anti-Western backlash.

The Naval Response

Most of the Iranian naval response would be in the hands of the smaller missile-equipped boats of the highly-trained and motivated Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps Navy (IRGCN) rather than the conventional and often outdated ships of the regular Iranian Navy.

Iran’s oft-stated intention of closing the Strait of Hormuz to commercial traffic, primarily oil shipments, is no secret. According to General Jaafari: “If a war breaks out where one side is Iran and the other side is the West and the U.S., it’s natural that a problem should occur in the Strait of Hormuz. Export of energy will be harmed. It’s natural that this will happen” (Fars News Agency, September 16).

Though it is frequently pointed out that Iran would itself suffer greatly by closing the Strait, it is likely that the Iranian command has recognized that in the event of a war Iranian oil could only be shipped with U.S. sufferance. With the United States unlikely to be so generous, the Iranian command may have come to the conclusion it has nothing to lose by closing the Strait, which would at least bring international pressure to bear on finding a quick resolution to the conflict. Domestic support for a U.S. role in the conflict could falter as rapidly rising petroleum prices drive a fragile economy into recession. Of course closing the Strait is not without risk and could incite the entry of the most affected countries (Kuwait, Iraq, Oman and Qatar) into a larger Sunni Arab – Shiite Iranian conflict.

Speedboat attacks could cause a certain amount of mayhem in the narrow confines of the Straits, but are unlikely threaten U.S. naval ships in any significant way. Analogies to the 2000 USS Cole attack are meaningless; if the Cole had been on security alert or felt endangered by the skiff approaching its side the smaller craft would have been quickly blown out of the water. With air surveillance support, American warships have ample short-range defenses to deal with aggressive craft should they succeed in coming within attacking range. Rather than attack warships, Iran’s fleet of small missile boats would be better employed in attacking civilian shipping in the Gulf. Attacks on oil tankers in particular would cause economic havoc in the international markets.

In the last few months the United States has doubled the number of minesweepers it maintains in the Gulf, sent a second aircraft carrier to the region two months ahead of schedule and deployed the USS Ponce, an amphibious transport dock that can be used as a staging base for Special Forces operations or as a carrier for MH-53 helicopters in a minesweeping role (Financial Times, September 17).

A large-scale de-mining exercise, the September 16-27 International Mine Countermeasures Exercise (IMCMEX), involving ships from the United States, Britain, Japan, France, Jordan, Yemen and other nations was designed to test a variety of anti-mine techniques to address the Iranian threat to close the vital Strait of Hormuz with fixed or floating mines (Hurriyet, September 17). General Jaafari downplayed the significance of the exercise (at least in public), describing it as “defensive” in nature: “We don’t perceive any threats from it” (Reuters, September 17).

Soft Warfare

Iran’s response will not be limited to military activities. An important part of its strategic planning is dedicated to Iran’s “Soft War” concept, which describes an alternative form of warfare that, in the hands of Iran’s enemies, is dedicated to eroding the legitimacy of the Islamic republic by changing the cultural and Islamic identity of Iranian society. To handle Iran’s response to such attacks, a special “Unit of the Soft War” (Setad-e Jang-e Narm) was created in 2011 as a branch of the Basiji militia. Iranian Soft War counter-measures include propaganda, education, media manipulation and the management of electronic information access (for a full description of the “Soft War” concept, see Terrorism Monitor, June 12, 2010). General Jaafari remarked in early September that soft warfare was more dangerous than conventional warfare and urged university and seminary students and faculty to prepare to deal with the soft warfare strategy employed by Iran’s enemies (Tehran Times, September 2).

Social Networking may provide a unique and innovative way of organizing hundreds or even thousands of points of simultaneous resistance to an attack on Iran in a variety of forms ranging from public demonstrations to civil resistance to armed activities or terrorist attacks. The drawn-out nature of the dispute over Iran’s nuclear capabilities and intent has allowed Iran’s global intelligence network to prepare a broad “soft warfare” response to any attack.

Border Defense

In the event of land-based incursions into Iran, the Deputy Commander of the Iranian Army, Brigadier General Abdolrahim Mousavi, has promised Iran’s borders will be defended by a combination of the regular Iranian Army, the IRGC and the Basiji Force (a lightly-armed but highly motivated militia) (Press TV, September 23).

Iran enhanced its border defenses in March with the introduction of the Shaparak (Butterfly) unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV), though the drone has an operational radius of only 31 miles and a flight time of three and a half hours. Since then Iran has added the Shaed-129, which can remain in the air for 24 hours and deliver strikes with its Sadid missiles (Fars News Agency, September 16). The most important drone in the Iranian arsenal is the Karrar (Striker), a turbojet-powered drone capable of long-range reconnaissance and attack missions with a flight range of 1,000 km at low or high altitudes. The four-meter long drone can be deployed on the back of a truck to a ground-launch position where it can be fired with the aid of a jet-fuelled take-off system (see Terrorism Monitor Brief, November 25, 2010; Ressalat [Tehran], August 23, 2010; Vatan-e Emrooz [Tehran], August 23, 2010).

Possible Foreign Support for Iran

In observing the current North American coverage of the approaching crisis it is easy to assume that the whole world, or most of it, is resolutely opposed to Iran. This, however, is not the case, as shown by the 120 nations that attended the Non-Aligned Movement conference held in early September in Tehran despite calls from Western nations for a boycott. Iran is aware of the political value even a defeat could have for the Islamic Republic in the international arena. As suggested in a feature carried by Iran’s state-owned Press TV: “In the impossible event that all goes well for Israel on the battlefield, the suffering of the people of Iran would probably shame the world into turning against Zionism even more sharply than the world turned against apartheid in the 1980s” (Press TV, September 21).

In the state of heightened tension and trepidation that would follow an Israeli attack, incidents that might otherwise be dealt with at an appropriate level could easily precipitate a chain of events leading to the entry of other nations or militant groups into a wider war. Following a series of international incidents, Turkey’s ruling AKP government has gone from shifted from being Israel’s military ally to an increasingly hostile neighbor. Ankara is seriously disturbed by Iran’s role in Syria and demonstrated its dissatisfaction by recently keeping Iran’s national security chief cooling his heels for half an hour prior to a meeting in the office of Turkish prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Nevertheless, in the unpredictable environment that would emerge from an Israeli attack on Iran it is entirely possible that some incident could drag Turkey into a larger war, whether as a result of a government decision, national security concerns or popular pressure. While Israel displays little respect for the militaries of Iran or the Arab world, Turkey’s powerful, well-trained, well-armed and battle-experienced armed forces are another matter. Certainly, as a NATO member, an entry into the conflict by Turkey could immeasurably complicate the entire situation.

With a large Palestinian population and a growing Islamist movement, Jordan represents another Israeli neighbor that might find itself hard-pressed to resist popular pressure to retaliate in some form if Israel attacks Iran, possibly by annulling its peace treaty with Israel. Jordan is pursuing its own nuclear power program, which is much needed as a dependable replacement for unreliable natural gas supplies from Egypt and to fuel desalinization plants required to provide the arid nation with water. Jordan’s King Abdullah II recently complained that: “strong opposition to Jordan’s nuclear energy program is coming from Israel… When we started going down the road of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, we approached some highly responsible countries to work with us. And pretty soon we realized that Israel was putting pressure on those countries to disrupt any cooperation with us” (AFP, September 12).

So long as the volatility in Syria and the Sinai continues, there is ample opportunity for unintentional clashes or planned provocations to light the charge for a wider conflict. Under Egypt’s new Muslim Brotherhood government there is daily discussion of revising or even abandoning Egypt’s three-decade-old peace treaty with Israel. If Israel became entangled in battling Gaza militants or dealing with a new Palestinian intifada in the West Bank there would be enormous pressure both on the street and in the halls of government for Egypt to provide a military response. Hezbollah’s success in the 2006 summer war changed attitudes in the Middle East. The once-common perception of an invincible Israel with unlimited military and logistical support from the world’s largest superpower has not existed since Israel’s failed effort to destroy Hezbollah, which not only repulsed the Israeli Defense Force (IDF), but did so without even having to call up its reserves. While Israel has worked hard to revise its battlefield tactics and took advantage of its 2009 incursion into Gaza to field-test them in what amounted to a massive live-fire exercise considering the lack of resistance encountered, the IDF has lost much of its ability to intimidate the Arab opposition. The ascendance of the Muslim Brothers in Egypt has also been a game-changer; no longer can Israel expect the silence of a corrupt and self-indulgent regime fattening itself on American aid. Today there is a growing assumption in Egypt that billions of dollars in American military aid will not last much longer, paired with a recognition that Egypt must develop its own arms industry if it is to pursue an independent foreign policy.

Disaffected Shiite populations in eastern Saudi Arabia and Bahrain, while not necessarily following directives from Tehran, could still take advantage of a collapsing security situation to press their demands for economic and political reforms. Such instability in Bahrain would not prevent operations by the U.S. Sixth Fleet based there, but would prove politically embarrassing at an extremely sensitive time. If violence can sweep the Muslim world because of the actions of Florida Quran burners and Californian immigrant film-makers, imagine the violence that would follow a carefully manufactured false-flag operation or other provocation designed to draw various countries or populations into a new Middle East conflict.

Conclusion

Despite the Middle East’s vast energy resources, reserves are declining in some areas and have nearly expired in others. Some major nations, like Egypt and Iraq, are largely or partially reliant on hydro-electric power that is threatened by huge new dams being built further upstream in Ethiopia and Turkey respectively. With even oil-rich Saudi Arabia intent on expanding its nuclear power capabilities before the oil runs out, it is clear that the future of the Middle East is nuclear. In these circumstances it would be impossible for Israel to continue a policy of pre-emptive strikes on potentially hostile neighbors to prevent the possibility of nuclear weapons development. Without the emergence of alternative energy supplies, even the deterrent effect of a successful Israeli strike on Iran will be short-lived in the region.

Iran has consistently exaggerated its military capability and the effectiveness of its weapons, so much of its rhetoric concerning its ability to retaliate to an Israeli or American attack must be taken with a grain of salt. In addition, much of the conventional response outlined above is subject to the operational survival of Iranian weapons systems to a unilateral or joint Israeli/U.S. strike, which would target Iranian missile silos and electrical systems nation-wide. Cyber-attacks could also be expected to destroy Iran’s ability to respond with sophisticated hardware or weapons. With these considerations it becomes clear that Iran’s most effective response will lie in the areas of asymmetric warfare and economic disruption. In the complicated world of the Middle East, Iran could still organize a broad retaliatory response that would effectively prevent an Iranian military defeat from translating into an Israeli victory.

This article first appeared in the September 27, 2012 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.