Eurasia Daily Monitor Vol. 22, Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC

Andrew McGregor

March 6, 2025

Executive Summary:

- Moscow is pursuing the construction of a naval port on Sudan’s Red Sea coast, reflected in the finalization of an agreement between Russia and Sudan in February.

- The deal appears to be part of the Kremlin’s efforts to create new strategic assets in Africa following the loss of air and naval bases in Syria.

- The elected government of Sudan’s inability to ratify the agreement reflects the salience of domestic and international opposition to a changed security situation on this vital maritime trade route.

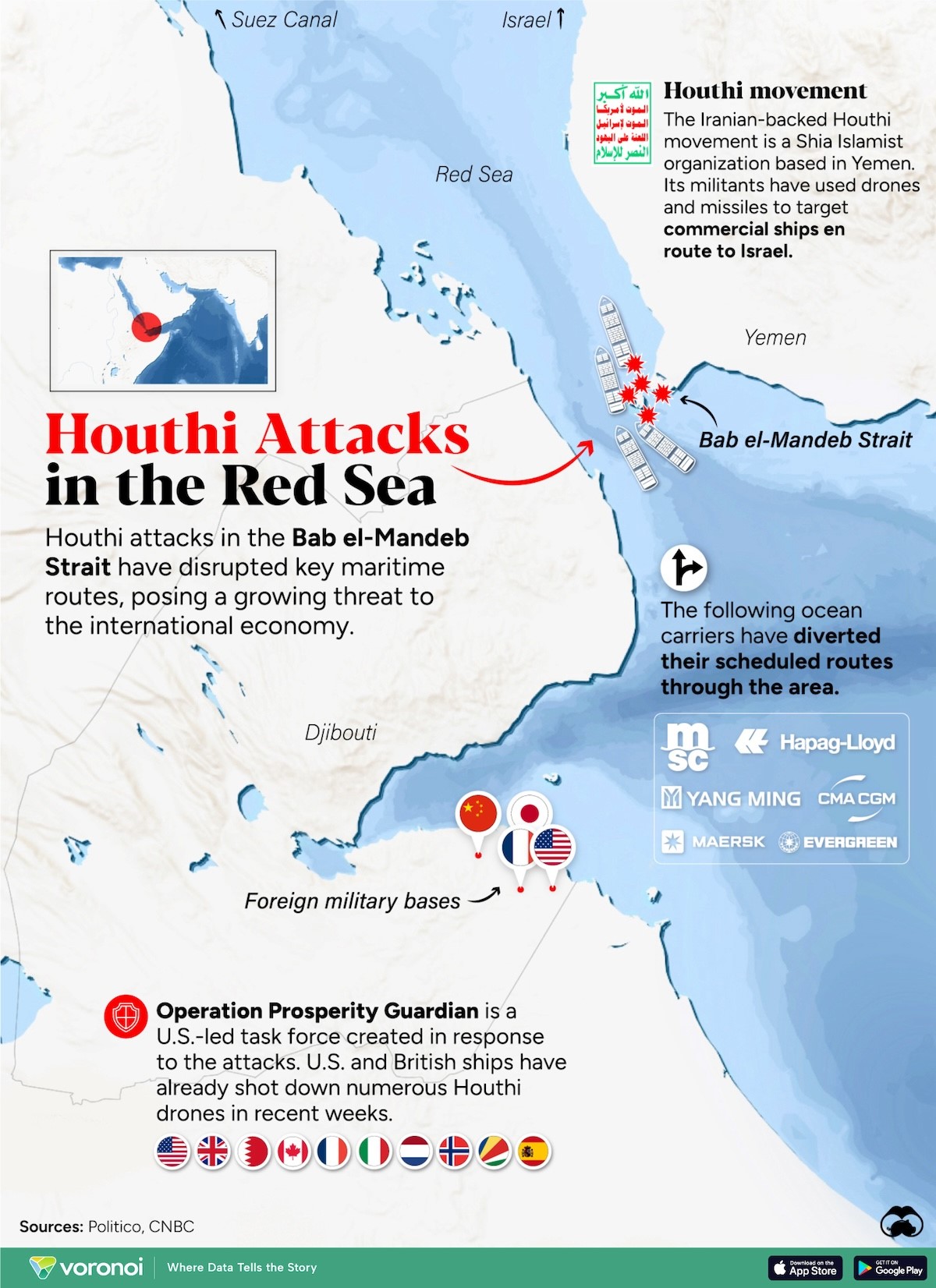

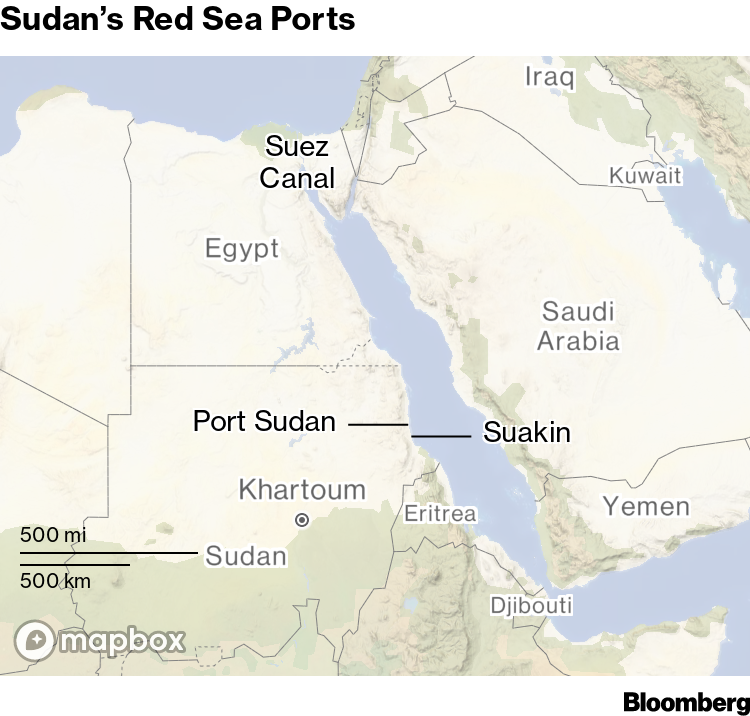

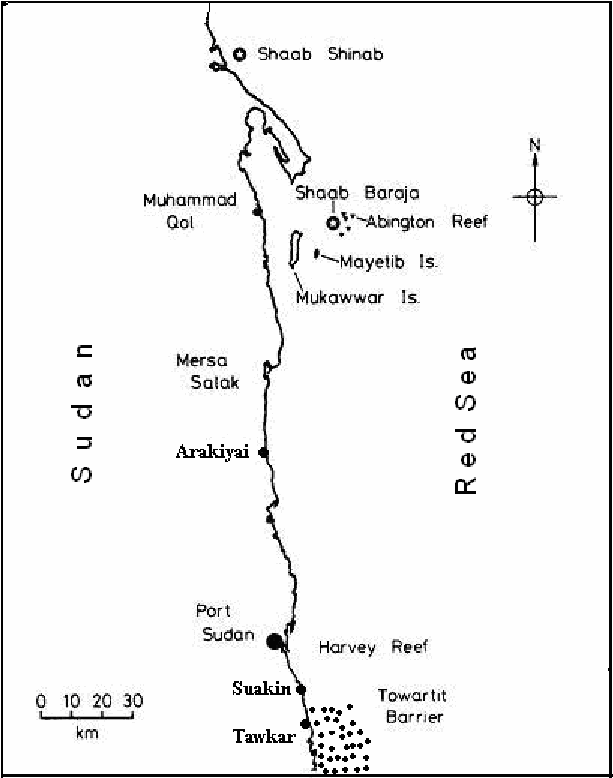

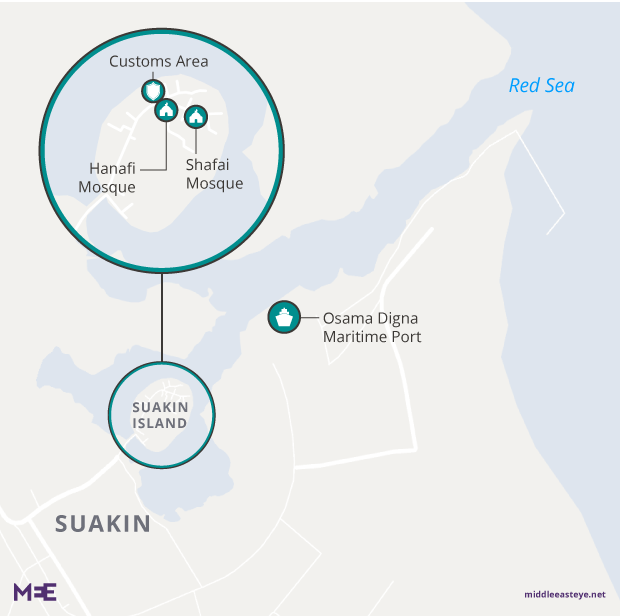

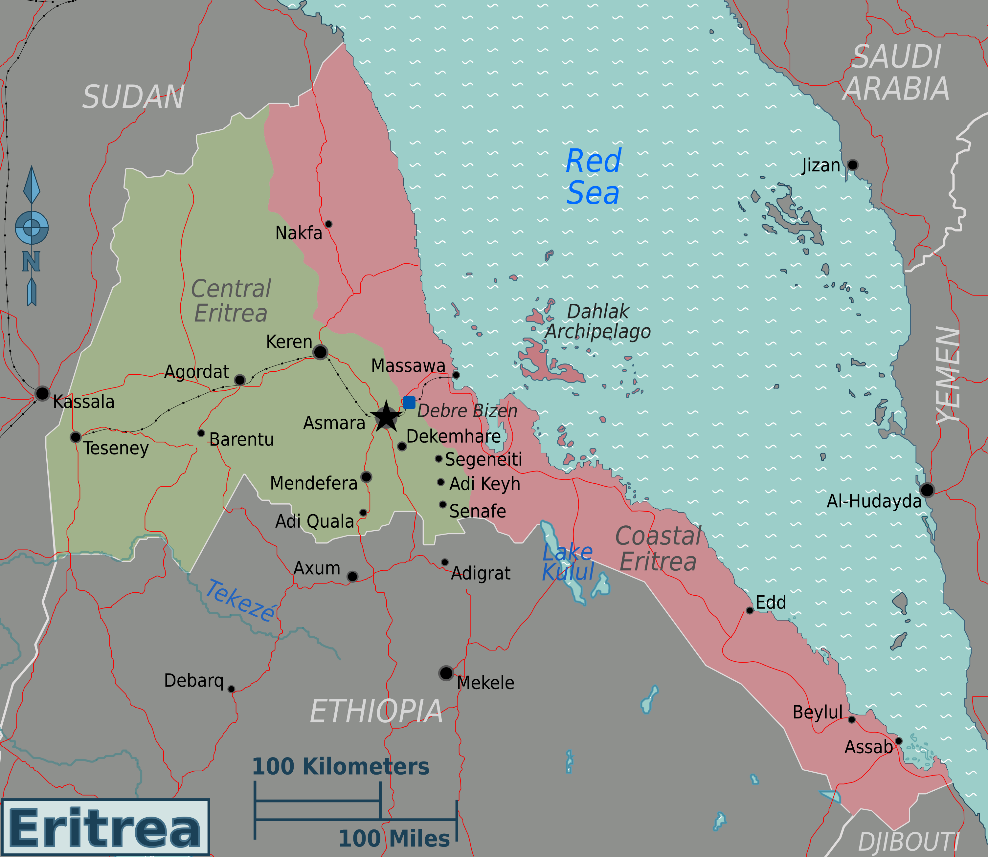

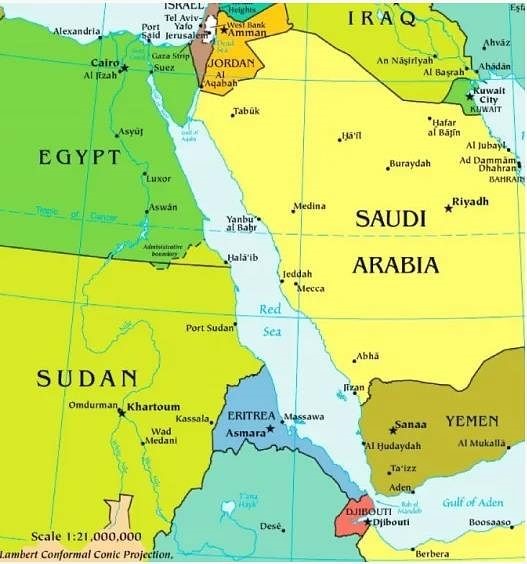

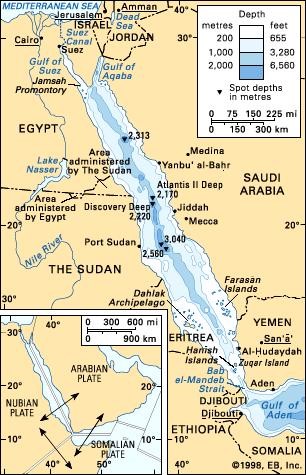

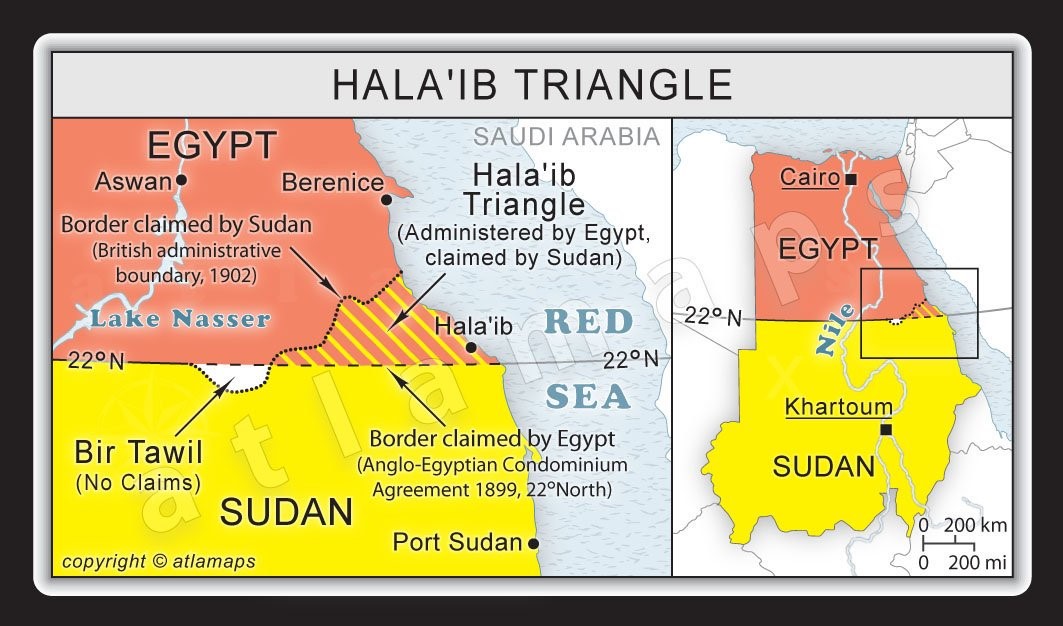

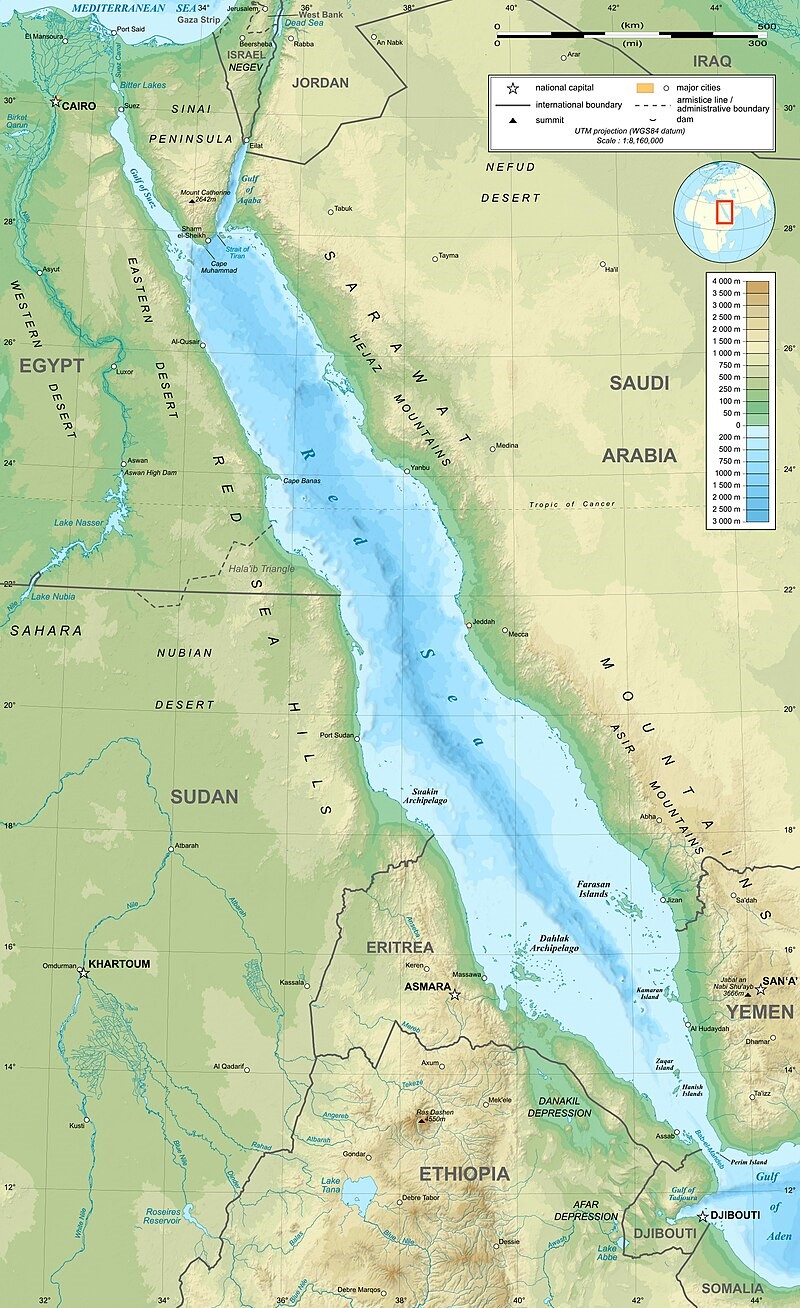

Russia and the leading faction in Sudan’s ongoing civil war have reportedly finalized an agreement to establish a Russian naval base on the Red Sea coast. Since the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, there may be no more strategically important body of water in the world than the Red Sea. Access to the sea, which carries 10 to 12 percent of global trade on its waters, is gained only through the Egyptian-controlled canal to the north and the narrow Bab al-Mandab strait to the south (The Observatory of Economic Complexity, accessed March 4). So far, no state outside of the region has established a naval base between the canal and Bab al-Mandab since the departure of the British from Sudan’s primary Red Sea port, Port Sudan, in 1956. That appeared to change on February 12 with the announcement that an agreement had been reached to construct a Russian naval base in Port Sudan.

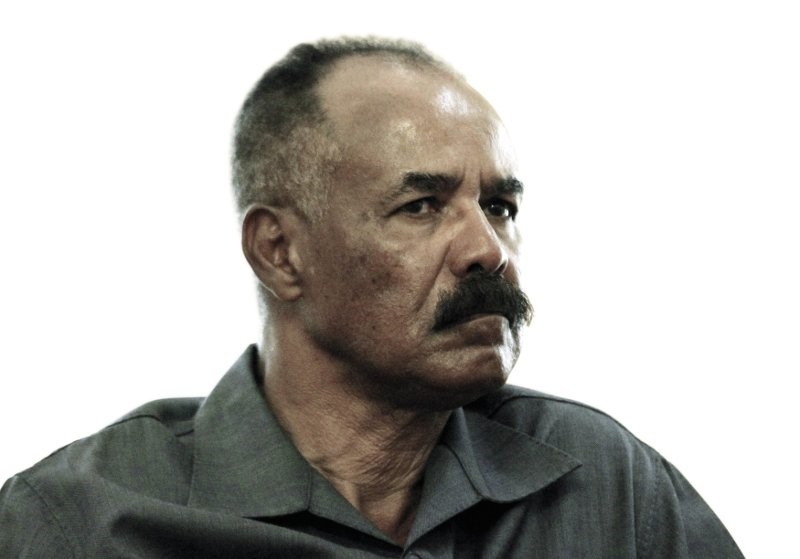

The announcement was made by Dr. ‘Ali Yusuf Sharif, appointed in November 2024 as nominal foreign minister by Lieutenant General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, whose faction controls most of Sudan. During a televised press conference in Moscow with his Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov, Sharif said “This is an easy question, there are no obstacles, we are in complete agreement” (Izvestiya, February 12; Al Arabiya; Atalayar, February 13). After the meeting, Lavrov expressed his appreciation for the “balanced and constructive position” taken by Sudan on the situation in Ukraine (TASS, February 12). There has been no confirmation from Moscow of the official signing of this deal.

The announcement was made by Dr. ‘Ali Yusuf Sharif, appointed in November 2024 as nominal foreign minister by Lieutenant General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, whose faction controls most of Sudan. During a televised press conference in Moscow with his Russian counterpart, Sergey Lavrov, Sharif said “This is an easy question, there are no obstacles, we are in complete agreement” (Izvestiya, February 12; Al Arabiya; Atalayar, February 13). After the meeting, Lavrov expressed his appreciation for the “balanced and constructive position” taken by Sudan on the situation in Ukraine (TASS, February 12). There has been no confirmation from Moscow of the official signing of this deal.

‘Ali Yusuf Sharif and Sergei Lavrov

‘Ali Yusuf Sharif and Sergei Lavrov

Since 2017, Moscow and Khartoum, represented by the since-deposed Sudanese president, ‘Omar al-Bashir, have discussed the creation of a Russian naval base in Sudan (See EDM, December 6, 2017). A preliminary agreement, forming the basis for the current pact, was developed in 2020 but never implemented. This original agreement includes a 25-year lease with a possible ten-year extension (Uz Daily, November 15, 2020).

Moscow holds a vested interest in establishing a naval base in this region, especially as the future of its naval base in Tartus, Syria remains uncertain (Military Review, December 11, 2024; Izvestiya, January 22). The primary function of Russia’s new “logistical base,” as it is described by Moscow, is to repair and replenish up to four Russian naval craft at a time, including nuclear-powered vessels. The base will house up to 300 personnel, with an option to increase this number with Sudan’s permission (TASS, February 12; Sudan Tribune, February 12). Russia will be responsible for air defense and internal security, while Sudan will provide external security in tandem with temporary Russian defensive positions outside the base. Russia will be at liberty to import and export weapons, munitions, and military material to and from the base (Vreme, February 13).

Sukhoi Su—25 Aircraft (Military Africa)

Sukhoi Su—25 Aircraft (Military Africa)

The completion of the deal may open the possibility for Sudan to purchase Russian-built SU-30 and SU-35 fighter jets, which it has sought since 2017 (Sudan Tribune, July 16, 2024). The sale has been complicated by an inability to finalize the port offer, U.S. sanctions on Russian manufacturers, and Sudan’s difficulty in making payments. Oil-rich Algeria, by comparison, has just completed a deal to obtain 14 fifth-generation Russian SU-57 stealth fighters (Janes.com, February 14).

Cooperation with Russia is also attractive to Sudan given Khartoum’s need to secure oil exports on its coast. Port Sudan serves as the export point for Sudan’s troubled oil industry, now operating at only slightly more than 40 percent of pre-war production. Sudan’s Ministry of Energy and Petroleum (MOP) is currently discussing a new partnership with Russia related to exploration, financing, and technical assistance (Sudan Tribune, January 25). In November 2024, MOP Minister Dr. Muhyaddin Na’im Muhammad Sa’id met with his Russian counterpart in Moscow to discuss prospects for joint projects and attractive areas for Russian companies to invest in oil and gas exploration (Sudan News Agency, November 16, 2024). The People’s Republic of China (PRC) was formerly Sudan’s main energy partner. According to one Sudanese economic expert, “the [civil] war has changed this equation” in favor of gaining expertise, especially related to oil extraction, from Russia (Sudan Tribune, January 25).

Sudan Began to Run Out of Fuel, Medicines and Wheat When Beja Protests Closed Port Sudan in 2021 (AFP)

Sudan Began to Run Out of Fuel, Medicines and Wheat When Beja Protests Closed Port Sudan in 2021 (AFP)

For Russia, there is a risk in initiating the construction of an expensive naval facility during a period of continued instability in Sudan. There is also the question of overland supply from Khartoum to Port Sudan, which essentially follows a single highway that has been blocked in the past by Beja protestors (New Arab, October 27, 2021; see EDM, November 14, 2023). To mitigate such risks, Sudan appears to be trying to follow the “Djibouti approach” to hosting foreign military bases. Djibouti currently hosts separate French, Chinese, U.S., Italian, and Japanese military facilities while U.K. forces are hosted at the U.S. facility (see EDM, July 8, 2024). According to Sharif, the new Russian base in Sudan, like those in Djibouti, will not pose a threat to the sovereignty of its neighbors nor Sudan itself (Anadolu Ajansi, February 13).

There are, however, major and ongoing differences between the military and civil components of the de facto government in Port Sudan that could sideline Russian ambitions in the Red Sea. Sharif’s claim that there were “no obstacles” to implementing the agreement is not necessarily correct. There is broad opposition to the unelected leaders of the Transitional Sovereignty Council (TSC) and Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) making a deal with major implications for Sudanese sovereignty (see Terrorism Monitor, April 28, 2023). As the deal cannot presently be ratified by any elected body in Sudan, there is a strong possibility that a future government (elected or otherwise) might reject the deal entirely as having no legal legitimacy. The January 20 cancellation of Russia’s 2017 49-year lease on the port of Tartus by the new Syrian regime provides an exemplary lesson on such a danger (Maritime Executive, January 21).

Another approach the Sudanese leadership may use to mitigate security risks, and in turn, may increase Russia’s attraction to creating a naval base in the country, is via deliberate changes in government representation. The de facto leader of Sudan is Lieutenant General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, chair of the unelected Transitional Sovereignty Council and commander-in-chief of the Sudanese Armed Forces. Al-Burhan’s government is now located in Port Sudan rather than war-torn Khartoum. Al-Burhan differs from previous leaders, as he has attempted to garner support from eastern Sudan, a traditionally impoverished area with little influence or representation in the central government. Most of the rebellions, coups, and civil conflicts that have plagued Sudan since independence and effectively prevented its successful development have been sparked by the inequality, domination, and monopolization of power. Since eastern Sudan has been dominated since independence by the Arab Nubian elites of northern and central Sudan, al-Burhan’s emphasis on involving eastern Sudan in his government represents a measure to prevent future coups or conflict. One of the figures who will likely be involved in establishing a Russian naval base in Sudan is ‘Umar Banfir, the new trade minister. Banfir is the former director of Sudan’s Sea Ports Authority and is expected to represent eastern interests to the government (Jordan Times, November 4, 2024).

Sanctions imposed by the United States on the SAF and al-Burhan personally in the last days of the Biden Administration appear correlated with al-Burhan’s renewed interest in securing the naval base deal with Russia (US Treasury Department, October 24, 2024; US Department of State, January 16; US Treasury Department, January 25).

Meanwhile, there is little evidence to suggest that the new Trump administration will impose additional sanctions or attempt to restrict Sudan’s pursuit of a new deal with Russia given the previous removal of sanctions under the first Trump administration (Congressional Research Service, July 5, 2017). Nearby Egypt and Saudi Arabia remain firmly opposed to the deal (Sudan Tribune, July 16, 2024).

Domestic political opposition, foreign objections, tribal unrest, and local fears that a Russian base might attract attacks from rivals, which in turn could damage or shut down Sudan’s most important port, remain considerable threats to the construction of a Russian naval facility in Port Sudan. These considerations also threaten Russian attempts to reinvigorate Sudan’s oil production, which has been declining for years due to a lack of investment and civil conflict. While the Russian naval base deal in Sudan holds strategic potential for Moscow, its success hinges on overcoming these political, domestic, and regional challenges.