Eurasia Daily Monitor

Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC, November 6, 2023

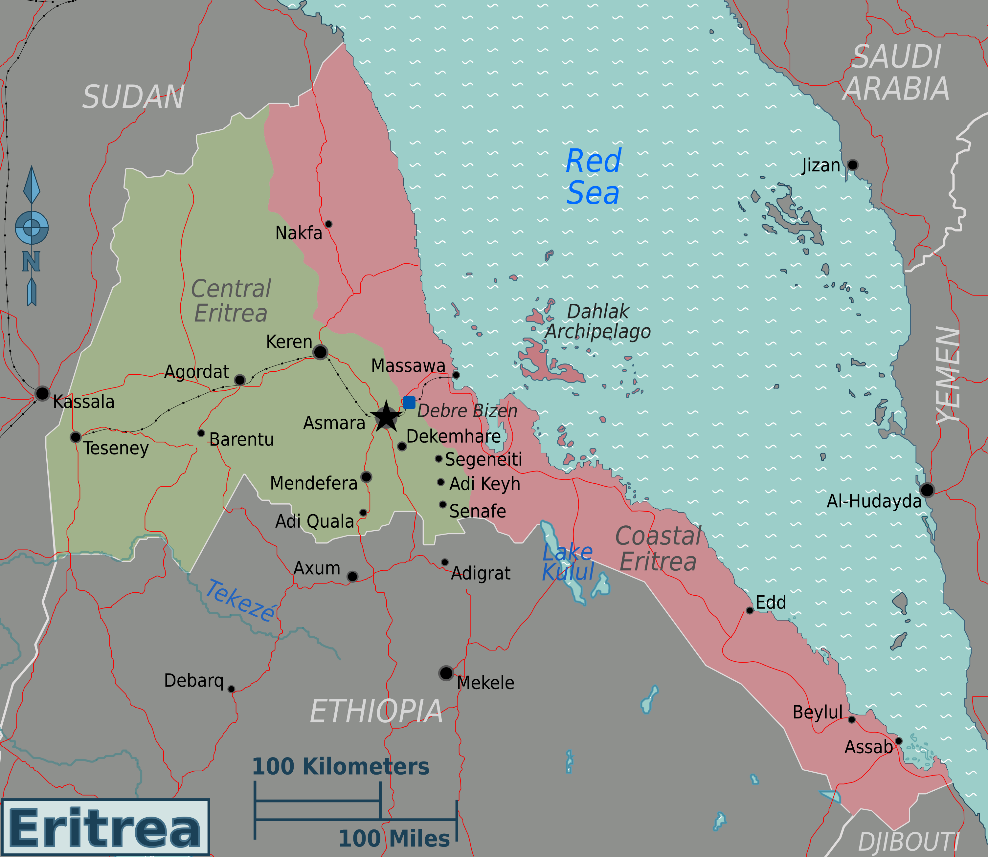

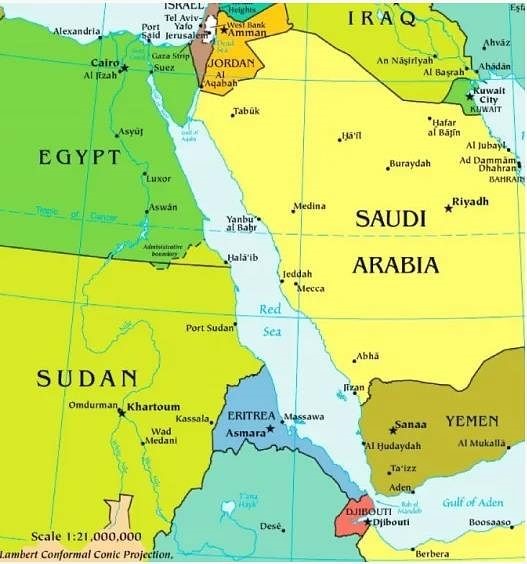

As Russian military and financial resources are being ground down in Ukraine, Moscow has struggled to maintain progress in some of its wider foreign policy objectives. Some of these are a revival of Soviet-era goals, including a greater military, political, and economic presence in Africa and the establishment of more warm-water ports along major maritime trade routes. In September, it was reported that Eritrea was keen on expanding military and economic ties with Russia, reiterating its potential openness to hosting a foreign base in the future (Adf-magazine.com, September 5). A Russian base on the Red Sea would provide a southern complement to the small Russian Mediterranean naval facilities undergoing expansion at Tartus and Latakia in Syria. It would also place Russian warships within striking distance of both sides of the Suez Canal.

Control of the southern Red Sea and its trade routes have been highly sought after historically. Located at the north end of the Gulf of Zula, Massawa has a medium-sized, deep-water port that provides a maritime outlet for Asmara. During the rule of Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie (1930–1974), Massawa was frequently visited by US warships bringing supplies to the Cold War military base at Kagnew. These visits came to an end with the 1974 Ethiopian Revolution and Mengistu Haile Mariam coming to power. Mengistu was open to the establishment of a Soviet naval base at Massawa, but Eritrean separatists in the area prevented the implementation of such plans. Eritrea’s 1991 victory in its war for independence and the Soviet collapse brought a temporary halt to Russian ambitions in the Red Sea region.

Moscow considers a strong naval presence in the Red Sea as vital to its economic interests in the region. Close to 15 percent of global trade, including Russian oil, passes through this narrow sea headed to or coming from the Suez Canal (Egypt Today, June 6, 2022). In February, Sudan was ready to offer a Red Sea port to Russia in exchange for arms and other considerations. Clashes broke out in April between factions of the Sudanese military, however, and the deal was put on hold indefinitely (Sudan Tribune, February 11).

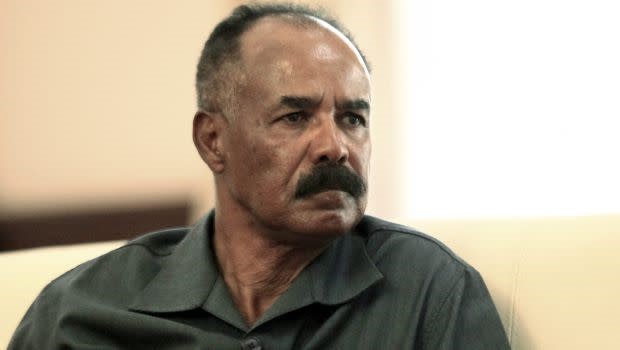

Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki (Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah / Reuters)

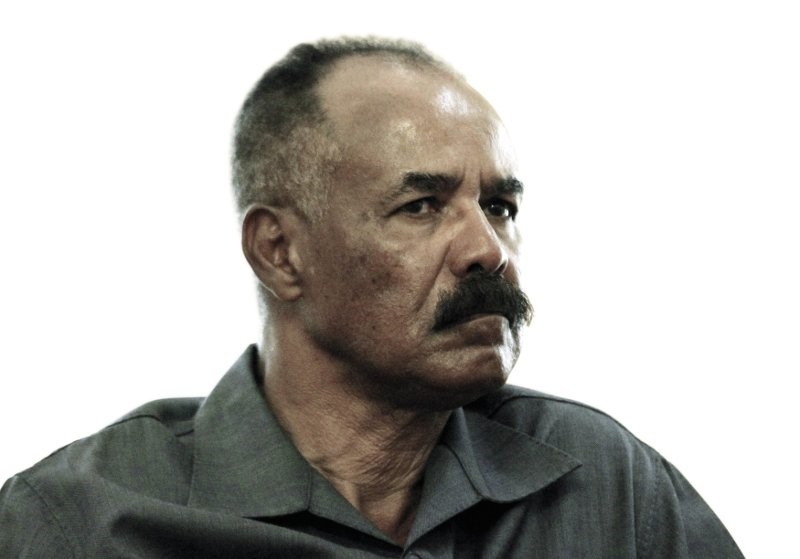

Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki (Mohamed Nureldin Abdallah / Reuters)

Just south of Sudan, Eritrea’s position on the Red Sea provides Moscow with other options. Eritrea has not welcomed Wagner Group personnel on its territory, but its authoritarian dictatorship feels much closer to Russia than the West. The regime of President Isaias Afwerki, the nation’s only leader since independence in 1993, may believe that a Russian military presence on its soil could deter Western efforts at regime change. Eritrea has three primary areas of interest to Russian naval planners: the ports of Massawa and Assab and the offshore Dahlak Archipelago.

Vladimir Putin’s efforts to restore Soviet-style “greatness” to Russia has led to a recent revival of interest in Massawa and other potential naval ports on the Red Sea. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov began negotiations to establish a logistical base in Eritrea in August 2018 during Eritrean Foreign Minister Osman Saleh’s visit to Sochi (RIA Novosti, August 31, 2018). More recently, in January 2023, Lavrov relayed Moscow’s interest in the Massawa port and airport, insisting that “concrete steps” were needed to protect Russian-Eritrean cooperation from Western sanctions (Interfax, January 27; TASS, January 26). Earlier, the Eritrean ambassador to Russia, Petros Tseggai, had announced the signing of a memorandum of understanding between Massawa and the Russian naval port of Sevastopol (RIA Novosti, January 8).

The establishment of a Russian military presence in Eritrea is not without its difficulties. A Russian base in Massawa would place foreign military forces only 70 miles from Eritrea’s xenophobic regime in Asmara. As a result, both Eritrea and Russia might prefer setting up a base at Assab, 283 miles south of Massawa at the northern entrance of the Bab al-Mandeb strait. Assab would be attractive to the Russian side largely due to the massive improvements made to the harbor by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) between 2015 and 2019 (Madote, November 5).

Satellite photo of Assab after UAE military withdrawal, February 5, 2021(Planet Labs Inc. via AP)

Satellite photo of Assab after UAE military withdrawal, February 5, 2021(Planet Labs Inc. via AP)

Eritrea agreed to host a UAE air and naval base at Assab in 2015. Asmara allowed for this due to the increased threats coming from Houthi insurgents and al-Qaeda terrorists across the Bab al-Mandeb strait in Yemen. The Emiratis dredged a new channel, built a new pier, and lengthened the airstrip to 3,500 meters. In 2019, the UAE decided to wind down its participation in the Yemen war and began stripping everything out of the port at Asmara, even dismantling barracks and hangars. By February 2021, there was little trace of the UAE’s presence other than the improved port facilities, leaving a potential opening for other foreign powers to capitalize on the port’s modernized infrastructure (Arab Weekly, February 18, 2021).

Italian colonial prison at Nakuru, Dahlak Archipelago (Shabait.com)

Italian colonial prison at Nakuru, Dahlak Archipelago (Shabait.com)

The Dahlak Archipelago may also be intriguing to Moscow based on its strategic location. The archipelago consists of two large and 124 smaller islands that sit 35 miles off Eritrea’s Red Sea coast. Only seven of the islands are inhabited and most are far too small to be of any military use. In 1982, US intelligence reported the presence of a Soviet naval facility at Nakuru (or Nocra), one of the archipelago’s largest islands. Other reports of foreign militaries using the archipelago have come out in more recent years. Both the Yemeni government-in-exile and Eritrean dissidents have claimed Asmara gave permission to Iran and Israel to operate military and intelligence facilities in the archipelago, though the Eritrean government has denied such allegations. An investigation of the islands in 2010 failed to find any trace of foreign troops or facilities on the larger islands of the archipelago (Gulf News, April 21, 2010). These allegations resurfaced in 2015 but suffered from a similar lack of evidence (Ahram Online, June 15, 2015). While this means the archipelago is effectively open to the development of port facilities, the Kremlin may shy away from such an expensive and intensive endeavor.

Russian efforts to gain a foothold in region have been hampered by its war against Ukraine and competition with other countries. For example, despite mutual pledges of a “no limits” partnership, Russia is competing with China for influence in the Horn of Africa and wider Red Sea region. Eritrea is growing closer to Beijing in developing numerous infrastructure projects, including improvements to the Port of Massawa (Mfa.gov.cn, May 15). China has operated a naval station in Djibouti since 2017, while France, the United States, and Japan also have military facilities in the small nation on Eritrea’s southern border (Defense.gov, November 5). The fighting in Ukraine and increased international competition for influence in Africa will likely stunt Moscow’s efforts to establish a warm-water port on the Red Sea in the near future, though that does not mean the Kremlin will give up on pursuing this goal altogether.

This article first appeared in the November 6, 2023 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor.