Andrew McGregor

Jamestown Foundation, Washington DC

January 19, 2017

Advocating loyalty to the regime may seem a rather uncontroversial and unprovocative stance in most instances. However, one influential Saudi shaykh, Rabi’ bin Hadi al-Madkhali, has taken this position to such extremes that many of his fellow Salafists regard him as a radical dangerously out of touch with the practice of the Salafist manhaj (method). Though his importance has declined in his homeland, his message of eternal loyalty to the ruler has gained him the support of individuals and certain governments throughout the Islamic world and beyond. In Libya, especially, we may be witnessing the militarization of a movement once best known for its quietist approach to politics.

Early Years and Education

The future preacher was born in the village of Jaradiya in Saudi Arabia’s southwestern Jazan region in 1931. His birth made him a member of the Mudakhala tribe, part of the larger Banu Shabil confederation. The boy’s father died before Rabi’ was two and a paternal uncle gave the boy guidance. From the age of eight, al-Madkhali studied Islam locally before attending the newly-opened Islamic University of Madina in 1960. Graduating in 1964, al-Madkhali then pursued a Master’s degree in hadith studies (1977), followed by a doctorate at the University of Umm al-Qurra in Mecca (1980) that allowed him to take up a full professorship at the Islamic University of Madina. [1]

The Birth of Madkhalism

Al-Madkhali’s strong opposition to the Muslim Brotherhood emerged in 1984 at a time when Egypt’s Brothers were beginning to engage in parliamentary politics by running candidates under the banner of the centrist and secular New Wafd Party (the experiment was largely rejected by the voters and was not repeated). Initially, al-Madkhali was also reluctant to embrace the Saudi rulers, but by the early 1990s he became a firm exponent of the Islamic legitimacy of the Wali al-Amr (“Guardian,” or “One vested with authority,” i.e. the ruler). In practice this meant he and his followers were stepping back from political engagement in favor of improving Islamic observance amongst the people.

Madkhalism as it has evolved calls for unquestioning loyalty to governments, even those that use extreme and unjustified violence against their subjects so long as they do not commit clear acts of infidelity. This extreme position separates the group from other Salafist movements who draw line at unjustified violence inflicted upon Muslims. However, like most Salafist movements, Madkhalism rejects participation in multi-party democracy on the grounds that it inspires loyalty to individuals and organizations rather than to God.

The Saudi royal family took notice, and in the years following the First Gulf War, al-Madkhali’s doctrine brought him financial support from the Saudi government, which wished to use his movement to weaken the growing Sahwa movement (opposed to the American military presence in the Kingdom, which al-Madkhali defended) and to discredit the emerging Salafi-Jihadist movement. [2]

Al-Madkhali was among half a dozen religious scholars who were asked to supply fatwa-s in support of the Muslim Jihad in eastern Indonesia’s Maluku Province (1999-2002). The scholar ruled that the jihad was individually obligatory for Muslims as they were allegedly under attack by Christians. [3]

Al-Madkhali’s movement takes an aggressive ideological stance towards other interpretations of Salafism. Al-Madkhali’s following has been described as similar to a cult in its demands for members to offer unquestioning obedience to its clerics. Similar to certain religious cults, al-Madkhali’s followers spend a disproportionate amount of time refuting criticisms of their leader or his more controversial works, usually by deploying a broad collection of positive remarks or reviews from members of the Saudi religious establishment as evidence of his legitimacy. [4]

Shaykh Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani

Shaykh Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani

Most of the scholar’s 30+ books concern hadith studies and have been received favorably by much of Saudi Arabia’s Salafist establishment, including hadith specialist Shaykh Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani. [5] Al-Madkhali studied under al-Albani in the 1980s but in recent years the latter has displayed a preference for Salafi scholars more radical than al-Madkhali. [6] Other leading members of the Saudi religious establishment have backed away from support of the preacher in recent years, contributing to the decline of the movement within the Kingdom.

The Spread of Madkhalism

Even as Madkhalism declined in influence in Saudi Arabia, the movement began to spread to Europe (particularly the Netherlands), Southeast Asia, Kuwait, Kazakhstan. Libya and Egypt (where the government promotes it as a Salafist alternative to Salafi-Jihadism). In Europe, the Madkhalists have little interaction with their host communities, preferring to avoid the temptations of Western life or attempts to convert European Christians. Followers are closely monitored for ideological conformity and are encouraged to read only pre-approved texts. Ideological competitors are likewise watched so that any refutation of Madkhalism on theological grounds can be quickly addressed by the scholar’s followers. Members of the movement typically refer to their Muslim opponents as Kharajites (Arabic: khawarij, “outsiders,” a seventh century Islamic movement that opposed the manner of succession in the early Caliphate and were known for their habit of declaring their opponents apostates to Islam, the practice of takfir).

Al-Madkhali has a habit of referring to Salafi-Jihadists solely as “Qutbists” to deny their legitimacy as Salafists. The term refers to the late Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood leader Sayyid al-Qutb, who was executed in 1966 for plotting the assassination of General Gamal Abd al-Nasser and the Islamist overthrow of the Egyptian government. Al-Madkhali has repeatedly targeted Qutbist ideology in sermons and books such as Spreading the Light on the Creed and Ideology of Sayyid Qutb, The Abuses of Sayyid Qutb against the Companions of the Messenger of Allah and Protection from the Dangers that are found in the Books of Sayyid Qutb. [7] Unsurprisingly, the jihadists regard the preacher as an enemy. Al-Madkhali has been attacked repeatedly by Abu Qatada al-Filistini, an important al-Qaeda leader now resident in Jordan. Abu Qatada accuses the “so-called Salafi” of spying on jihadis for the Saudi government. [8]

To promote his message, al-Madkhali maintains a website that deals with a range of Islamic issues, ranging from tricky theological debates to rulings on whether it is permissible to take one’s maid on pilgrimage. [9] He and his followers are also active in social media. [10]

The Salafi community in Kuwait began to split in the 1980s when Salafists belonging to Jamaiat Ihya al-Turath al-Islami (Revival of Islamic Heritage Society – RIHS, a Kuwaiti Salafi umbrella group) began to participate in the political process. Madkhalism, with its strict opposition to political participation, offered an acceptable ideology for these Salafists and has grown in popularity. [11] Madkhalism is one of several Salafist sects to take root in western Kazakhstan in recent years, though wary authorities tend to lump it together with more radical Salafist groups. [12]

In Egypt, al-Madkhali’s most prominent follower is Shaykh Muhammad Sa’id Raslan, a well-known former Muslim Brother who is now an opponent of the Brotherhood and party politics in general. Armed with a Ph.D. in hadith studies and strongly influenced by the controversial teachings of mediaeval preacher Ibn Taymiya (a staple for non-political Salafists and Salafi-Jihadists alike), Raslan has devoted himself, like al-Madkhali, to refuting the works of Sayyid Qutb. Raslan advocates political quietism within Egypt, though he may be taking a more aggressive approach in neighboring Libya (as seen below).

The Shaykh’s opponents are many however, and typically describe Madkhalism as “mental illness,” “fake Salafism” or bid’ah (innovation in religion, a serious transgression in Salafist Islam). [13] Detractors claim that submissiveness to the Wali al-Amr as prescribed by the Madkhalists produces passivity, submission to injustice and indifference to the suffering of fellow Muslims.

The Madkhalists in Libya

One common practice in man’s attempts to manipulate nature is to introduce a non-native species to control the proliferation of a native species or an undesirable intrusive species. In this spirit, the Madkhali movement was invited to Libya in the 1990s by Mu’ammar Qaddafi to offset the Salafi-Jihadism of al-Jama’a al-Islamiya al-Muqatila bi-Libya (Libyan Islamic Fighting Group – LIFG), which was threatening to overthrow Qaddafi’s regime at the time. [14] However, just as introduced species may proliferate and become an even greater problem than the one they were intended to solve, Madkhalism has taken root in Libya and has even infiltrated government-allied security services years after the disappearance of the LIFG as a coherent group.

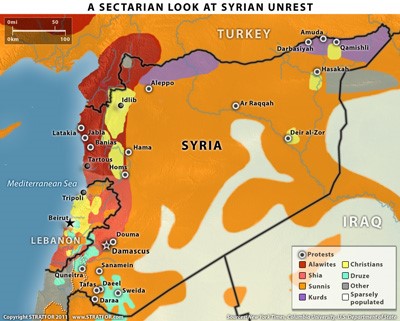

During the 2011 revolution, al-Madkhali called on his Libyan followers to remain home, declaring participation to be fitnah, creating sedition against a lawful ruler (amongst other connotations that include falling into sin and hypocrisy). [15] The charge had an especially loaded meaning, having been used to describe the bitter civil wars that tore apart the early Muslim community in the 7th to 9th centuries C.E. The Madkhalis also opposed the anti-Assad rebellion in Syria on the usual grounds and disparaged those Salafists who supported it. [16]

Destruction of a Sufi Shrine in Zlitan

Destruction of a Sufi Shrine in Zlitan

In 2012 Rabi’s brother Muhammad (a professor at the Islamic University of Madinah) led the demolition of Sufi shrines in Libya. Sufism is despised by Salafists on the grounds that it promotes the idea of an intermediary (or “saint,” usually a deceased Sufi leader known for exceptional piety and knowledge) who intercedes between man and God. On August 24, 2012 Muhammad directed the demolition of a Sufi shrine in Zlitan (Murqub district on the Mediterranean, west of Misrata) using bulldozers, jackhammers and explosives. The Madkhalists went on to destroy the neighboring mosque and a library containing 700-year-old documents (France24.com, August 29, 2012). The demolition of the tomb of Abd al-Salam al-Asmar, a 15th-century Muslim scholar, followed by the demolition of the historic Sha’ab mosque in Tripoli while security forces looked on led to the resignation of the Interior Minister (al-Jazeera, August 26. 2016). [17]

In February 2015, al-Madkhali issued a fatwa issued forbidding participation in the battle between the largely Islamist and Tripolitanian Dawn coalition and the largely secular and Cyrenaïcan Operation Dignity forces led by General (now Field Marshal) Khalifa Haftar. [18] This was in keeping with Madkhalist principles, but in July 2016, al-Madkhali issued another fatwa urging all Libyan Salafists to join Haftar’s forces in fighting against the Benghazi Defense Brigade (BDB) led by Misrata’s Brigadier Mustafa al-Sharkasi and loyal to Libyan Chief Mufti Sadiq al-Ghariani. [19] The fatwa’s justification was that the BDB’s real objective was not to relieve Islamist fighters besieged in Benghazi, but to destroy Benghazi’s Salafist community. Perhaps influenced by the presence of Ismail al-Salabi (brother of prominent Libyan Muslim Brotherhood member Ali Muhammad al-Salabi) among the BDB commanders, al-Madkhali insisted the group was simply another manifestation of the Muslim Brothers, whom he described as more dangerous than Christians and Jews (Libya Observer, July 14, 2016). [20] In the process al-Madkhali ignited a feud with al-Ghariani, who accuses the Madkhalists of acting as spies and assassins for unnamed Gulf nations (Digital Journal, November 24, 2016).

Madkahli’s Libyan supporters use an estimated 30 FM radio stations to make their opposition known to al-Ghariani and the militias loyal to him (Digital Journal, November 24, 2016). In July 2016, the Shura Council of Libya’s Muslim Brotherhood denounced al-Madkhali’s attacks on the Grand Mufti (who they generally support) and called for Libya’s government to stop the Saudi government’s “blatant interference” in Libyan affairs (Ikhwanweb.com, July 19, 2016).

The adherence of Madkhalists in eastern Libya to Haftar’s camp since 2014 has created suspicion amongst those Libyans who view the Field Marshal as an ambitious interloper at best or an American intelligence asset at worst. Most of the armed Madkhalists supporting Haftar initially did so as part of the Salafist Tawhid Brigade commanded by the late Izz al-Din al-Tarhuni. After al-Tarhuni’s death in February 2015, the Tawhid Brigade broke up and its members joined various other units of Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA). [21] Madkhalists also joined in the successful offensive by the al-Bunyan al-Marsous coalition against Islamic State terrorists in Sirte, where their message may find some support after years of fighting have nearly destroyed the city, a former Qaddafi-era showpiece.

The Omrani Affair

Among those militias in which Madkhalist influence is strongest is the RADA Special Deterrence Force. RADA is a Tripoli-based militia that maintains security and operates smaller units elsewhere in Libya. Islamist in nature and led by Abd al-Rauf Kara, the unit is an independent formation under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior. Working out of a base at Tripoli’s Mitiga airport, the unit mounts operations against terrorists, criminal gangs, drug traffickers, kidnapping rings and arms smugglers, maintaining its own private prison at Mitiga. RADA opposes al-Ghariani’s influence and, following the principle of Wali al-Amr, is a strong backer of the Tripoli-based Presidency Council, the latest attempt to impose a united administration on fractured Libya.

‘Abd al-Rauf

In November 2016, an individual named Haitham al-Zintani confessed to being the assassin of Shaykh Nadir al-Omrani, a member of al-Ghariani’s Dar al-Ifta Islamic Research and Studies Council who was kidnapped in Tripoli on October 6, 2016 (the shaykh’s body has not been found, but he is presumed dead on the basis of the confession).

According to the suspect, the kidnapping was carried out by a RADA sub-group called the Crime Fighting Apparatus (CFA), a Tripoli-based unit strongly tied to Madkhalism: “We wanted to kill the shaykh because he presented an ideology different from Salafi scholars and clerics, especially that of Rabi’ al-Madkhali” (Libya Observer, November 21, 2016). Al-Omrani was also known to have been critical of specific fatwa-s issued by al-Madkhali. The murder was allegedly carried out by the CFA leader Abd al-Hakim Emgaidish and the CFA mufti Ahmad al-Safi on the order of leading Egyptian Madkhalist Muhammad Sa’id Raslan. Al-Zintani added that RADA holds regular meetings to plot the death of clerics they consider tied to the Muslim Brotherhood or other radical Islamist groups (Libya Herald, November 21, 2016; Libya Observer, November 21, 2016). RADA disclaimed any responsibility for the alleged assassin in a November 21, 2016 statement: “The force condemns strongly this crime but also condemns suggestions that it was involved in it” (Libya Observer, November 21, 2016).

Amidst popular outrage over the (presumed) murder, al-Ghariani took to Dar al-Ifta’s Tanasuh TV to denounce Saudi interference in Libya: “We want the Saudi Madkhali ideology to take its hands off the Libyan crisis, we know that the Salafis and Madkhalis here in Libya are the ones who killed Al-Omrani because he is moderate in Islam and they are radicals… These people [i.e. RADA] are receiving instructions from some Arab Gulf states to kill Libyan clerics” (Libyan Express, November 26, 2016; Libya Herald, November 23, 2016). Tripoli’s Awqaf and Islamic Affairs Authority banned 15 Madkhalist imams from preaching in Tripoli mosques as well as banning works by al-Madkhali, Raslan and their followers (Libya Herald, November 23, 2016; Libya Observer, November 24, 2016).

Conclusion

The fact that al-Madkhali’s fatwa-s on Libyan affairs have been contradictory has not added to his credibility in Libya. The question is why al-Madkhali should be issuing contradictory rulings; is the Madkhalist ideology in a state of flux? Or do these fluctuations represent, as some have suggested, fluctuations in Saudi foreign policy? [22] In Saudi Arabia’s religiously backed monarchy, the line between supporting the system and being an agent of the system is often blurred.

The declining importance of the doctrine of Wali al-Amr in 21st century Islam is partly due to growing international radicalization that ironically owes much to Saudi Arabia’s efforts to promote and finance the worldwide expansion of Salafism. While the secular and reformist wave of Arab Spring protest movements has been largely driven back by more traditional sources of authority (monarchies, militaries and political/economic elites), public distrust of such sources of authority remains high in the Islamic world. The politically quietist approach of Madkhalism is in danger of losing relevance under these conditions, though we may be witnessing a shift in the movement’s doctrinal approach in Libya intended to further embed Madkhali influence. Al-Madkhali’s regular (if inconsistent) proclamations on Libyan affairs may suggest the radically loyal scholar may be eying the nation as a future base of operations and expansion into the Maghreb.

Notes

- “Biographie de Cheikh Rabi’ Ibn Hadi Al Madkhali,” Rabee.net, August 1, 2012, http://www.3ilmchar3i.net/article-biographie-de-cheikh-rabi-ibn-hadi-al-madkhali-110174180.html

- Jarret M. Bachman and William F. McCants, “Stealing Al-Qa’ida’s Playbook,” CTC Report, February 2006, pp.13-14, https://www.ctc.usma.edu//wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Stealing-Al-Qaidas-Playbook.pdf

- Sumanto al-Qurtuby: Religious Violence and Conciliation in Indonesia: Christians and Muslims in the Moluccas, London, 2016, p.66; Muhammad Najib Azza, “Communal Violence in Indonesia and the Role of Foreign and Domestic Networks,“ In Arnaud De Borchgrave, Thomas M. Sanderson and David Gordon (eds.) Conflict, Community, and Criminality in Southeast Asia and Australia, Washington D.C., 2009, p.25.

- Rabi’ al-Madkhali’s followers are often referred to as “Madkhalis” or the “Madkhaliya,”though they reject this usage much as other Saudi Salafists reject the terms “Wahhabi” or “Wahhabism” as they imply devotion to a man rather than God (in the latter case, the 18th century Najdi reformer Muhammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhab).

- A hadith (Arabic – “report”) is a report of the Prophet Muhammad’s sayings or actions as transmitted through reliable religious authorities.

- Roel Meijer, “Politicizing al-jarh wa-l-ta’di: Rabi b. Hadi al-Madkhali and the Transnational Battle for Religious Authority,” In Nicolet Boekhoff van der Voort, Kees Versteegh and Joas Wagemakers: The Transmission and Dynamics of the Textual Sources of Islam: Essays in Honour of Harald Motzki, Leiden, 2011, pp.380-81; Jarret M. Brachman, Global Jihadism: Theory and Practice, London, 2008, p.29.

- “Biographie de Cheikh Rabi’ Ibn Hadi Al Madkhali,” op cit.

- Abu Qatada, Bayn al-manhajayn (Between Two Methods),” articles 8 and 9, al-Nur, Denmark, 1994.

- http://www.rabee.net/ar/.

- An example of the type of hagiographical material produced by al-Madkhali’s followers can be found in Abu Khadeejah Abdul-Walid, “Is Shaikh Rabee’ Ibn Haadee a great scholar of this era?” http://www.abukhadeejah.com/is-shaikh-rabee-ibn-haadee-a-great-scholar-of-this-era/

- Zoltan Pall, “Kuwaiti Salafism and its Growing Influence in the Levant,” Carnegie Endowment Paper, May 7, 2014, http://carnegieendowment.org/2014/05/07/kuwaiti-salafism-and-its-growing-influence-in-levant-pub-55514

- Almaz Rysaliev, “West Kazakhstan under Growing Islamic Influence,” IWPR Reporting Central Asia no.653, July 21, 2011, https://wikileaks.org/gifiles/docs/54/5427694_reporting-central-asia-no-653-.html

- See for example: “Madkhalism (Madkhiliyyah) – A mental illness,” Islam is Sunnah, October 28, 2014, https://islamissunnah.wordpress.com/2014/10/28/madkhalism-madkhliyyah-a-mental-illness/, or Abu Hafs ash-Shamee, “Deviations of the Madakhilah!!!,” The Ghurabah, October 18, 2013, http://theghurabah.blogspot.ca/2013/10/who-are-madkhalis.html .

- Frederic Wehrey, “The Authoritarian Resurgence: Saudi Arabia’s Anxious Autocrats,” Journal of Democracy, April 15, 2015, http://carnegieendowment.org/2015/04/15/authoritarian-resurgence-saudi-arabia-s-anxious-autocrats-pub-59790

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sriMveeY9vA

- Zoltan Pall, op cit.

- Rabi’ al-Madkhali’s views on Sufism are available in: Shaykh Muhammad Ibn Rabee’ Ibn Haadee Al-Madkhalee, The Reality of Sufism in Light of the Qur’aan and Sunnah, 1404 H. http://www.slideshare.net/Truths33k3r/the-reality-of-sufism-by-shaykh-rabi-bin-hadi-al-madkhali

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TOyYSJnLuaA

- The YouTube video announcing this fatwa is no longer available.

- For a profile of al-Ghariani, see Andrew McGregor, “Shaykh Sadiq al-Ghariani: A Profile of Libya’s Grand Mufti,” Militant Leadership Monitor, December 2014.

- Frederic Wehrey, “’Madkhali’ Salafists in Libya are active in the battle against the Islamic State, and in factional conflicts,” Carnegie Middle East Center, October 13, 2016, http://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/64846

- For the Saudi possibility, see Frederic Wehrey, ibid.