Andrew McGregor

Terrorism Monitor

November 2, 2018

Angry locals filled the streets of the Congo’s Nord Kivu province town of Beni on October 21, torching the post office, destroying parts of the town hall and throwing stones at vehicles belonging to health workers fighting a deadly outbreak of the Ebola virus. Eventually driven off by tear gas and live ammunition fired into the air, the demonstrators were enraged by the inability of Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) troops and UN peacekeepers to prevent yet another terrorist strike in the town that saw 11 people hacked to death and 15 others (including children) abducted by militants of the Allied Democratic Front (ADF) (Radio Okapi [Kinshasa], October 21; AFP, October 22, 2018).

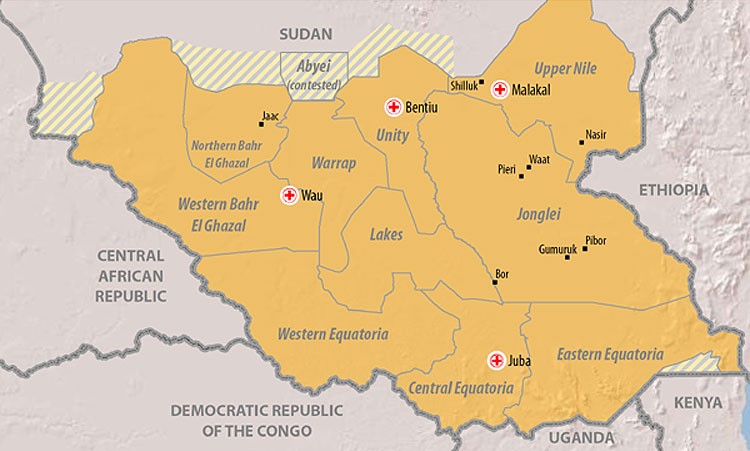

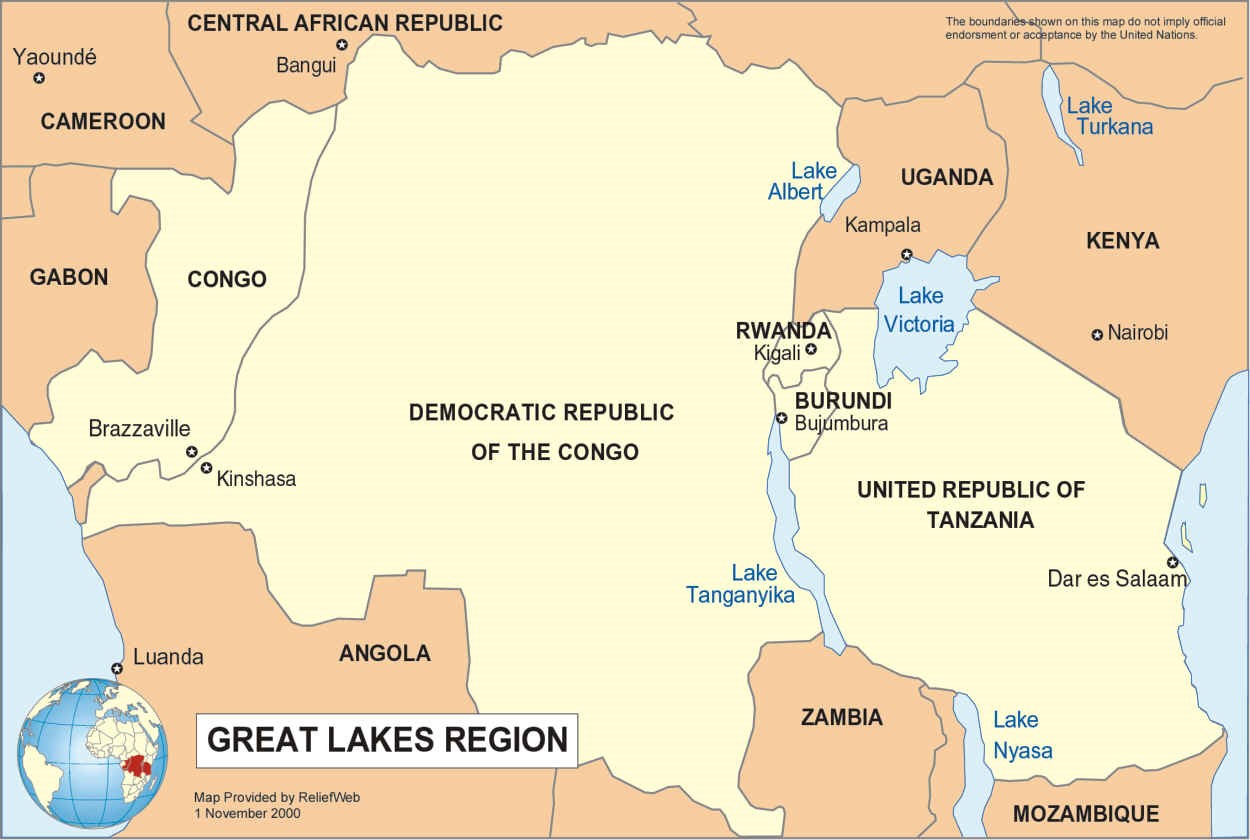

Nord Kivu province borders Uganda and Rwanda to the east and has absorbed defeated militant groups from both countries. Scores of armed groups are active in the region now despite the presence of large numbers of UN peacekeepers and troops of the Forces armées de la république démocratique du Congo (FARDC – Armed Forces of the DRC).

Nord Kivu province borders Uganda and Rwanda to the east and has absorbed defeated militant groups from both countries. Scores of armed groups are active in the region now despite the presence of large numbers of UN peacekeepers and troops of the Forces armées de la république démocratique du Congo (FARDC – Armed Forces of the DRC).

After two decades of ADF activity in the Uganda-DRC border region, ADF operations are now centered round the Nord Kivu town of Beni, a hub for regional trade routes. Beni is close to Virunga National Park, the Ituri Forest and the Rwenzori Mountains, all used at some point as bases for ADF activities. The region is rich in gold, tin, timber and diamonds.

The Allied Democratic Forces

The ADF has its roots in the Ugandan chapter of the Tabliqi Jama’at, an Islamic revival movement which began to claim political persecution in the 1990s. Many of the jama’at’s members left Kampala for the wild Rwenzori Mountains of western Uganda, where they formed the ADF by allying themselves with remnants of the Rwenzori separatist movement, fugitive Idi Amin loyalists and the National Army for the Liberation of Uganda (NALU), a group drawn from the Nande ethnic group of the Rwenzori Mountains. Today, most ADF members are locally recruited residents of Nord Kivu.

The ADF’s leader, Jamil Mukulu, was arrested in Tanzania in April 2015 and extradited to Uganda. When he was arrested, Mukulu was carrying no less than nine passports (Le Monde, May 15). Mukulu is a convert from Christianity who became involved in the Tablighi Jama’at and eventually adopted a Salafi-Jihadist stance with alleged ties to al-Qaeda (The Independent [Kampala], May 17, 2015).

The ADF was able to obtain Sudanese arms and training during the proxy war fought between Khartoum and Kampala, but this came to an end when the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement with South Sudan brought a finish to the proxy war.

The ADF has a low-profile and highly isolated leadership. Mukulu’s successor as leader of the main ADF faction is believed to be Imam Seka Musa Baluku, the subject of an Interpol red notice (Daily Monitor [Kampala], September 24, 2015). As the prospect of ever actually overthrowing the Ugandan government grows ever more distant, the movement has splintered, losing any sense of ideological cohesion in favor of extortion, illegal taxation and resource exploitation.

The ADF resents interference in it local economic operations; a 2014 statement made their approach clear:

You, the population, we are going to kill you because you have provoked us too much. The same goes for the FARDC with whom we used to live without any problems… Don’t be surprised to see us killing children, women, elderly… In the name of Allah, we will not leave you alone.” [1]

Other ADF factions include the Feza Group (more religiously inclined than the others), the Matata Group, the Abialose Group (commanded by “Major” Efumba) and the ADF-Mwalika. [2] Factional leaders have often married the daughters of local chieftains to strengthen local ties.

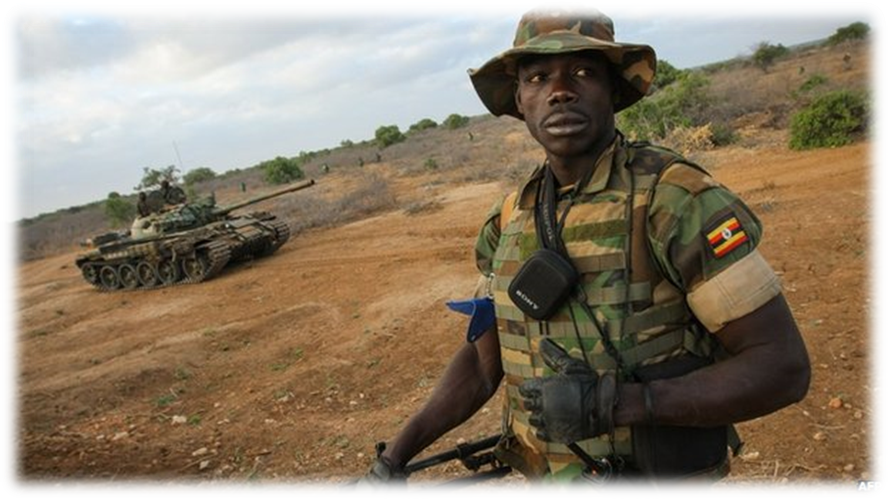

The Uganda Peoples’ Defence Force (UPDF) succeeded in expelling the ADF from Uganda in 1999 and the rebels re-established themselves across the border in the DRC’s lightly governed but resource rich Nord Kivu province. The ADF has posed little threat to Uganda since suffering heavy losses in battles with the UPDF in 2007-2008.

The situation in Nord Kivu, however, is different. Some 700 civilians have been killed by the ADF since violence intensified in the region in October 2014 (Le Monde, September 9). Well over 200 civilians have been killed by armed groups in over 100 attacks in the region around Beni this year. [3] Hundreds of thousands have been displaced. The poorly-armed ADF typically relies on the use of machetes and axes in its attacks on civilian population centers and relies on raids on military bases to obtain more advanced weapons. Fighters often abduct civilians and take them to their bases in the bush for use as sex slaves or porters. Children are trained to become ADF fighters. Women and children participate in ADF attacks, looting and finishing off wounded victims, including other women and children. [4]

Jamil Mukulu used to issue cassette tapes to condemn Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni and the leaders of the West while urging violence against non-Muslims. Since his detention, the movement has drifted from jihadist rhetoric, or, indeed, any rhetoric at all, making its current aims something of a mystery.

FARDC Troops Targeting ADF Positions

FARDC Troops Targeting ADF Positions

MONUSCO and the ADF

The UN’s Mission de l’Organisation des Nations unies pour la stabilisation en République démocratique du Congo (MONUSCO) was founded in 1999-2000. It is now the UN’s largest peacekeeping mission, with 17,000 troops and an annual budget of $115 billion. [5] The ADF, who travel light and known the difficult terrain intimately, have proven far more mobile than MONUSCO forces.

Fifteen Tanzanian peacekeepers and five Congolese troops were killed at Semuliki in the Beni region in a December 2017 ADF attack (Reuters, January 13). The assault followed earlier attacks on the Tanzanians in September and October2017. A UN investigation of the incident identified a number of weaknesses in MONUSCO: “The mission did not have an actionable contingency plan to reinforce and extract its peacekeepers… Issues of command-and-control, leadership and lack of essential enablers such as aviation, engineers and intelligence were also major obstacles and need to be addressed urgently” (Reuters, March 2).

The UPDF claimed to have killed over 100 ADF fighters in cross-border artillery and jet-fighter strikes (Operation Tuugo) on ADF positions following the attack on the peacekeepers (New Vision [Kampala], December 22, 2017; Observer [Kampala], December 28, 2017). Uganda is suffering a wave of assassinations and murders mostly tied to local tensions, though Museveni (without evidence) has blamed the ADF for many of the killings, including those of seven Muslim shaykhs between 2012 and 2016. He has also blamed the DRC and the UN for harboring and supporting ADF terrorists (AfricaNews, June 6).

Insurgency and Disease

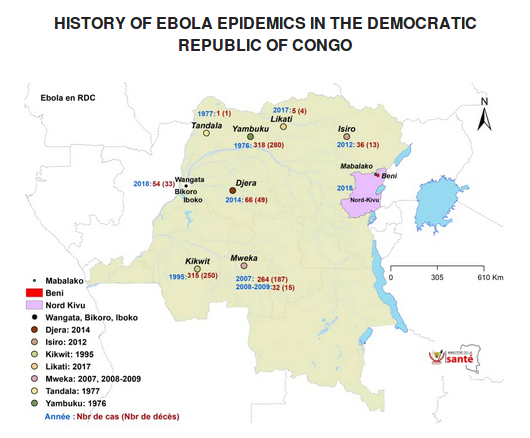

Ebola is a viral hemorrhagic fever with an extremely high fatality rate. The virus is spread through contact with the infected bodily fluids of people or primates (the latter is known as “bushmeat” by those who eat it, including ADF militants). Ebola emerged in the DRC in the 1970s and has since killed thousands across West Africa.

Nord Kivu Health Workers (AFP)

Nord Kivu Health Workers (AFP)

The epidemic was announced on August 1, shortly after an Ebola outbreak in the DRC’s Equateur Province. The epidemic might have been detected earlier, but local health workers were on strike after not having been paid for seven months (Actualité.cd [Kinshasa, August 2).

Though health officials have initiated a vaccination program, there are other factors besides the conflict that inhibit its implementation, including the region’s often difficult topography and a strong degree of resistance to vaccination in some communities, resulting in flight into the forest where health workers cannot reach them.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has warned the virus could spread to Uganda and/or Rwanda at any time. In a worrying trend, the organization notes the 19 health workers who caught the disease by October 11 had all been infected outside health facilities, pointing to Ebola’s spread in the larger community (Al-Jazeera, October 11).

In August, seven people were reported to be suffering from hemorrhagic fevers at Mboki, a village in the heavily forested southern region of the Central African Republic, close to the border with the DRC. The lightly inhabited area is frequented by a number of armed groups who often rely on bushmeat. Tests done on rebels arrested in the DRC and extradited to the CAR revealed 80 per cent of them had Ebola antibodies in their system, suggesting both contact with the disease and their potential role as transmission vectors. Emmanuel Nakoune Yandoko, head of the CAR’s Pasteur Institute, has met with leaders of some of these cross-border militant groups and believes they could be usefully integrated into a disease surveillance system as they also fear Ebola and other fatal diseases in the region (Le Monde, August 17).

A recent OXFAM report identified several challenges to combating Ebola in Nord Kivu, including:

- The need to change culturally-entrenched burial practices to reduce infection; Attempts by health workers to take over the burial of Ebola victims provoked attacks on them, forcing security forces to accompany health workers on such missions (Al-Jazeera, October 10).

- The need to solve the puzzle of how to provide security for health-workers in a conflict zone while using as few FARDC and UN troops as possible in order not to provoke local flight into the forest;

- Establishing health education programs in remote communities where Ebola is often ascribed to witchcraft;

- Given the security situation, it is important to avoid gathering civilians in large numbers for vaccinations or other distributions.

The threat to health workers is serious; two nurses were killed on October 19 and there are three to four attacks a week against medical personnel fighting the virus. Many experience being stripped by the people they are trying to help and having their clothes burned in front of them (Radio Okapi [Kinshasa], October 23).

On September 23, 18 people and four soldiers were killed in the streets of Beni. Most were the victims of machete attacks in an incident that again revealed the inability of the Congolese Army to secure even Beni’s urban center against the ADF, which looted shops until FARDC reinforcements arrived (AFP, September 24, Anadolu Agency, September 23). This attack and a second one on Oicha, a village about 12 miles north of Beni where Ebola cases have been identified, led to a 48-hour suspension in efforts to treat the spreading disease (AFP, September 25). FARDC and MONUSCO troops, who arrived well after the Oicha attack despite being based just outside the town, were met by stone-throwing civilians (AFP, October 11). In July 2016, 19 people were slaughtered only 300 meters from a Nepalese MONUSCO base at Eringeti despite an informant warning MONUSCO officers of the attack the day before (Le Monde, July 1, 2016).

FARDC Weakness and the Role of the UPDF

FARDC is far from a cohesive entity, being composed of both integrated and non-integrated former rebel factions with different languages and customs. President Kabila, who regards his army as a potential threat, relies for his own personal security on the three brigades of the Garde Républicaine. Pay problems are endemic and encourage trade and economic cooperation with the rebel movements they are intended to fight. There is little incentive to venture into the bush without remuneration.

With ADF militants wearing FARDC uniforms and operating with apparent immunity at times, there are major suspicions locally of FARDC corruption and collusion in the attacks. There is growing anger in the region at the military’s inability or unwillingness to bring armed groups under control. Locals arrested as suspected insurgents are often subject to summary executions. Many of the FARDC units operating in Kivu region are from western provinces of the DRC and tend to behave more as an occupation force than defenders of Kivu civilians.

Led by General Marcel Mbangu, FARDC launched its own anti-ADF operations independent of MONUSCO in January. Though the military promised a conclusive campaign, local residents have noted lethargy and inefficiency in FARDC’s efforts, which often appear to be focused on self-preservation rather than protecting the community. [6] Belief in collaboration between the two supposed antagonists is strong enough that locals refer to “the ADF FARDC” (Le Monde, March 6, 2017). Both FARDC and MONUSCO suffer from poor intelligence work due to the suspicion and fears of the Nord Kivu community.

Military cooperation between FARDC and the UPDF is limited to a UPDF presence on the border to prevent ADF militants from escaping Congolese operations. A Ugandan presence in the DRC is unwanted in Kinshasha, as tensions between the two countries have remained high since the 1998-2003 civil war.

Brigadier General Muhindo Akili Mundos

Brigadier General Muhindo Akili Mundos

Brigadier General Muhindo Akili Mundos, an ally of President Joseph Kabila and commander of the anti-ADF Sukola 1 (Lingala – “cleanup”) operation, was alleged by a confidential UN report to have recruited, financed and armed ADF elements and others to carry out attacks on local civilians over 2014-2015. Included in the supplies were FARDC uniforms. The Brigadier denied the allegations, pointing out killings had continued after his transfer from North Kivu (Reuters, May 14, 2016). The UN imposed sanctions on General Mundos in February on the grounds he had incited killings in Nord Kivu (Jeune Afrique, February 2).

Other FARDC officers suspected of working with the ADF have been tried by the North Kivu Military Operational Military Court. Colonel David Lusenge was tried on charges of supplying arms and ammunition to the ADF, as well as participating in the planning of attacks on Beni civilians (Radio Okapi [Kinshasa], February 15, 2017). A former senior ADF military instructor testified that Colonel Shabani Molisho and other FARDC officers supplied the ADF with ammunition in 2014 (Radio Okapi [Kinshasa], February 11, 2017). Colonel Katanzu Hangi was sentenced to 12 month in prison after being found guilty of collaborating with the ADF (Radio Okapi [Kinshasa], June 6, 2017). Though three colonels were eventually convicted, there was a marked reluctance by the court to pursue allegations against more senior officers.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, the ADF leadership has avoided any public proclamation of their aims or intents, expressing themselves solely through their direction of uninhibited violence. The last negotiations with the ADF came in 2008, but were even then complicated by divisions within the movement.

Growing public anger in Nord Kivu with the government and its security forces works against local cooperation with health workers or the Congolese military. President Joseph Kabila’s term expired last December, but his refusal to step down has ignited violence across the vast DRC, taxing the resources of both FARDC and the UN. With little chance of a negotiated settlement or a military victory in Nord Kivu, the international community must address the question of how to tackle epidemics of disease in failed or failing states before they spread across borders in a shrinking world.

Notes

- Report of the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office on International Humanitarian Law Violations Committed by Allied Democratic Forces (ADF) Combatants in the Territory of Beni, North Kivu Province, Between 1 October and 31 December, 2014, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/CD/ReportMonusco_OHCHR_May2015_EN.pdf

- United Nations Security Council, “Letter dated 23 May 2016 from the Group of Experts on the Democratic Republic of the Congo addressed to the President of the Security Council, May 23, 2016, http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/2016/466

- “DR Congo: Upsurge in Killings in Ebola Zone,” Human Rights Watch, October 3, 2018, https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/dr-congo-upsurge-killings-ebola-zone

- Report of the United Nations Joint Human Rights Office, op cit.

- https://monusco.unmissions.org/en/facts-and-figures

- “DR Congo: Upsurge in Killings in Ebola Zone,” op cit.

This article first appeared in the November 2, 2018 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.