Andrew McGregor

May 30, 2015

A full year after the planned departure date of the Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF) from its military intervention in South Sudan, the Ugandan military presence in South Sudan is growing in size and cost.

Though the Uganda government recently announced $5.4 million in funding for its military operations in South Sudan, the true costs of the mission are obscured by conflicting claims from Kampala and the South Sudanese capital of Juba. While Juba has insisted it is paying the cost of the deployment (which has prevented the overthrow of the Dinka-dominated South Sudan government of President Salva Kiir Mayardit by Nuer-dominated rebel groups), Ugandan MPs claim figures related to the South Sudan deployment have not been made available to the parliamentary defense committee responsible for approving them and demand to know who is funding the Ugandan military operations. In response, Ugandan Defense Minister Crispus Kiyonga said providing such details would endanger the lives of Ugandan troops in South Sudan, though he did not specify exactly how that would occur (Uganda Radio Network, April 24, 2015; Observer [Kampala], April 27, 2015).

Though the Uganda government recently announced $5.4 million in funding for its military operations in South Sudan, the true costs of the mission are obscured by conflicting claims from Kampala and the South Sudanese capital of Juba. While Juba has insisted it is paying the cost of the deployment (which has prevented the overthrow of the Dinka-dominated South Sudan government of President Salva Kiir Mayardit by Nuer-dominated rebel groups), Ugandan MPs claim figures related to the South Sudan deployment have not been made available to the parliamentary defense committee responsible for approving them and demand to know who is funding the Ugandan military operations. In response, Ugandan Defense Minister Crispus Kiyonga said providing such details would endanger the lives of Ugandan troops in South Sudan, though he did not specify exactly how that would occur (Uganda Radio Network, April 24, 2015; Observer [Kampala], April 27, 2015).

In early April, Ugandan government of President Yoweri Museveni came under criticism from John Ken-Lukyamuzi, the leader of the opposition Conservative Party, who claimed the Ugandan military mission in South Sudan “grossly violates international law.” The opposition leader cited a number of other problems with the mission:

- The actual deployment came before it was approved by a January 14, 2014 parliamentary vote;

- The mission’s extent has vastly exceeded the Ugandan government’s original declared intention to evacuate Ugandan citizens and protect the airport and presidential palace in Juba;

- No documentation of a formal invitation for Ugandan troops from the South Sudanese government has been provided despite a request from parliament;

- It is unclear who is paying for the UPDF’s presence in South Sudan (Observer [Kampala], April 9, 2015).

The Ugandan deployment was soon opposed by the other seven members of the regional trade bloc, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) who have continued without success to urge President Museveni to withdraw his forces and allow a political settlement to take shape.[1] Both the rebels and the United States have also called for a full withdrawal of foreign troops from South Sudan. Instead, South Sudanese media noted a major increase in the numbers of UPDF troops deployed in the region in February, 2015, claiming the size of the force had grown from 3,000 to 7,000 (Sudan Tribune, February 11, 2015; Uganda Radio Network, February 11, 2015).

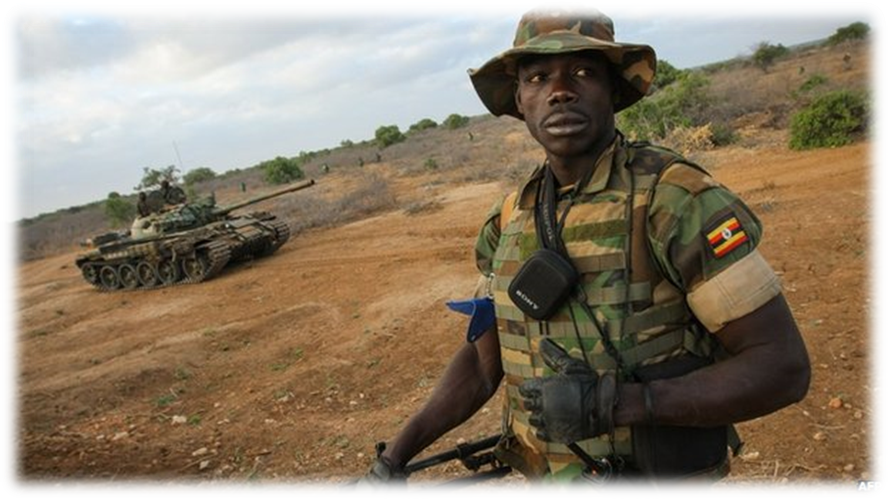

Uganda Chief of Defense Forces Katumba Wamala and Brigadier Kayanja Muhanga in Bor, 2014. Kayanja commands Ugandan forces in South Sudan. He is the former deputy commander of Ugandan forces in Somalia and is currently commander of the UPDF’s 4th Division.

Uganda Chief of Defense Forces Katumba Wamala and Brigadier Kayanja Muhanga in Bor, 2014. Kayanja commands Ugandan forces in South Sudan. He is the former deputy commander of Ugandan forces in Somalia and is currently commander of the UPDF’s 4th Division.

The UPDF, which has received extensive American training through its participation in the African Union Mission in Somalia and the anti-Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) Operation Lightning Thunder, consists of five divisions with one armored brigade and one brigade of artillery. President Museveni restructured Uganda’s Special Forces (including the Presidential Guard Brigade) into a new unit, the Special Forces Command (SFC), under the leadership of his son Brigadier Muhoozi Kainerugaba in 2012.[2] The move solidified Muhoozi’s meteoric rise through the ranks of the UPDF and gave him full control of well-trained and armed troops responsible for the security of all oil installations and important government facilities. According to Fungaroo Kaps Hassan, the opposition’s shadow minister of defense, “Muhoozi is the de-facto army commander… Museveni has personalised the army… He calls it his army and has put Muhoozi in-charge, which is why you see Muhoozi posturing, going to Somalia doing things that should be done by his seniors” (Independent [Kampala], February 1, 2015).

Juba’s reliance on the UPDF comes despite massive defense spending by the young state; a report released last week by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) revealed a steady rise in South Sudan’s military spending from $982m in 2013 to $1.08bn in 2014, making it the biggest spender in the region. As a non-diversified petro-state, South Sudan is almost entirely dependent upon oil revenues in a stagnant market while still devoting an astonishing 60% of its net income on the military (Sudan Tribune, April 26, 2015; East African [Nairobi], April 25, 2015). Insecurity in South Sudan has immediate economic effects on Uganda – South Sudan is Uganda’s most important export market.

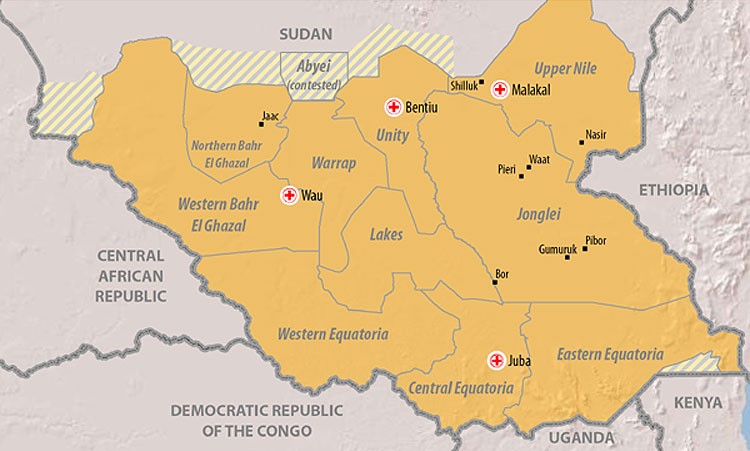

South Sudan

PROJECTIONS

The danger of Uganda’s deployment and the risk it may ignite a wider conflict was displayed in March, when Sudan’s state news agency reported the massing of 16,000 Ugandan troops along the border with (north) Sudan (SUNA, March 2, 2015). With Khartoum ready to act after receiving this alarming report, UPDF spokesmen were forced to issue quick denials to prevent an outbreak of hostilities between Sudan and Uganda, which have been fighting a proxy war for regional dominance for years at the expense of the region’s civilian population.

Juba is on the verge of economic collapse and cannot sustain its all-consuming defense budget, particularly as it comes at the expense of nearly all other forms of development and government services. No amount of defense spending will heal the political rift between Dinkas and Nuer (not to even mention the numerous other tribal rivalries that have spilled over into open conflict as a result of the current rebellion). Declining oil prices and interruptions in oil delivery through northern pipelines are placing financial strains on the Salva Kiir government.

Uganda will eventually present Juba with its bill for preserving the existing government; in earlier Ugandan interventions in the Democrat Republic of the Congo (DRC), these frequently took the form of concessions in resource-rich areas for leading Ugandan officers and friends of the Museveni regime. With discussions ongoing regarding a joint Ugandan-South Sudanese pipeline through Kenya to the Indian Ocean that would allow South Sudan to avoid Khartoum’s prohibitive transfer fees, Kampala may be looking to claim a share of South Sudan’s oil production, further assisting Uganda’s efforts to become a regional economic and military player in east Africa. This would also have the benefit of providing an additional pool of patronage funds to ease the political transformation from President Museveni to his son.

With a strong degree of opposition to such a move even within the UPDF (where Muhoozi is unpopular), Museveni’s efforts to turn Uganda’s single most important institution, its military, into a personal army loyal to the president alone may ultimately backfire, particularly at a time when similar efforts to extend presidential terms beyond constitutional limits or to create family dynasties in supposedly democratic systems are meeting heated opposition in many other African nations. Officers of the UPDF are forbidden from engaging in politics while serving; Museveni routinely denies UPDF officers who wish to enter opposition politics permission to resign their commissions, effectively bottling up opposition while simultaneously and inadvertently ensuring it has access to arms. Several senior officers who have managed to retire now figure in the leadership of several opposition parties despite starting out as Museveni loyalists during their military careers. President Museveni continues to surround himself with long-time loyalists in the upper ranks of the UPDF, but loyalty to Museveni does not necessarily extend to Muhoozi, who is viewed within the military as an arrogant upstart whose promotions have come at the expense of more senior and capable officers. The establishment of Uganda’s Special Forces Command as an army within an army under Muhoozi’s personal control is no doubt a response to this situation intended to guarantee a family dynasty in the president’s office, whether by acclaim or by force.

[1] Besides Uganda and South Sudan, IGAD includes Djibouti, Ethiopia, Sudan, Somalia, Eritrea and Kenya.

[2] Not to be confused with Ugandan land forces commander Major General David Muhoozi.