Andrew McGregor

September 14, 2006

“The Creation of a Caliphate in Russia is only the first part of their plan”

Russian Federation President Vladimir Putin, November 11, 2002.

Introduction

The last few years have seen a concerted effort by the pro-independence Chechen leadership to consolidate scattered Islam-based resistance movements across the North Caucasus. These locally based jama’ats (Islamic communities) champion a Salafist approach to Islam, a regional moral revival, and a steadfast opposition to Russian ‘colonialism’. In many ways these groups are Islamic inheritors of an earlier (and largely secular) pan-Caucasian movement. The late Chechen warlord Shamyl Basayev spent years developing ties to the independent jama’ats in order to bring them under Chechen command in a united North Caucasian front against Russian Federation rule.

The last few years have seen a concerted effort by the pro-independence Chechen leadership to consolidate scattered Islam-based resistance movements across the North Caucasus. These locally based jama’ats (Islamic communities) champion a Salafist approach to Islam, a regional moral revival, and a steadfast opposition to Russian ‘colonialism’. In many ways these groups are Islamic inheritors of an earlier (and largely secular) pan-Caucasian movement. The late Chechen warlord Shamyl Basayev spent years developing ties to the independent jama’ats in order to bring them under Chechen command in a united North Caucasian front against Russian Federation rule.

Basayev’s death on July 9, 2006, was a major setback to the expansion of the Chechen struggle to the rest of the North Caucasus, though it does not appear to have had much impact on the level of militant activity in the region so far.

The growth of the jama’ats as locally based centers of Islamist resistance raises a number of questions. How has the military jama’at evolved from its communal roots? How does it reconcile its Salafist ideology with basic pan-Caucasian sentiments? Most importantly, do the military jama’ats constitute a serious threat to the integrity of the Russian Federation? Some of the answers can be found through an examination of the origins of the military jama’ats, their connection to the pan-Caucasus movement, and their role in the expansion of the Chechen/Russian war through the North Caucasus and even into the Russian Republic itself.

Pan-Caucasus Movements

Though the Muslim North Caucasus is divided into scores of ethnic groups and as many languages, there have been significant attempts to unify these groups in the past, most significantly Imam Shamyl’s Islamic state of 1834-59 and the short-lived Mountain Republic of 1918. Soviet rule was designed to divide and weaken the region’s Muslims, but the collapse of the communist state allowed a revival of the pan-Caucasus movement.

The Confederation of the Mountain Peoples of the North Caucasus (KGNK) was formed in 1990 by a group of writers and academics, including its leader, Musa Shanib (a Kabardin, aka Yuri Shanibov) and the Chechen poet Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev. The Confederation had no representation from Dagestan and nor real constituency; the delegates were all self-appointed representatives of their peoples but did not include representation from Dagestan. In a move to be more inclusive the organization changed its name to the Confederation of the Peoples of the North Caucasus (KNK) in October 1992.

It was war that would galvanize the movement, with the KGNK declaring war on Georgia in support of the Abkhazian separatist movement in August 1992. A volunteer force of several thousand fighters was assembled, the ‘volunteer peace-keeping battalion of the Mountain Confederation’, composed mostly of Cherkess, Kabardins, Adigheans and Chechens. The Chechen ‘Abkhazian Battalion’ was the largest single volunteer unit and included the late Ruslan Gelayev and Shamyl Basayev, both of whom would go on to become major warlords in Chechnya. The volunteers, with covert training and equipment from the intelligence services of the Russian Federation, played an important role in helping the Abkhazians defeat a ramshackle Georgian paramilitary force. The involvement of the GRU (Russian Military Intelligence) in organizing and equipping KNK fighters led to persistent rumours that Shamyl Basayev was, and remained, a GRU officer until his death (see the recent remarks of Chechen parliamentary speaker Dukvakha Abdurakhmanov; Agentstvo Natsionalnykh Novostei, August 22, 2006). KNK leader Musa Shanib (a Kabardin, aka Yuri Shanibov) came under suspicion from Russian authorities for suspected separatist activities and was arrested in September 1992. Shanib escaped (or was possibly released) a short time later following a public outcry over his detention.

The fall of the Abkhazian capital of Sukhumi to Abkhazian and KNK fighters in October 1993 marked the peak of the KNK’s strength and influence. The collapse of North Caucasian solidarity began with disputes over unfulfilled promises made to the KNK fighters over compensation for their efforts. With the outbreak of war in Chechnya in 1994 the Kremlin began to regard the KNK as a threat to the unity of the Federation. Moscow had no desire to see a North Caucasian legion joining the Chechen separatists, but support for the Chechen cause from the other North Caucasus republics actually proved to be weak. A rift formed with Chechen leaders who felt their defence of Abkhazia had entitled them to similar support from their fellow Muslims in their independence struggle.

Confederation fighters were not especially welcome in largely secular Abkhazia, particularly those considered Islamists. Because of different forms of worship practiced throughout the North Caucasus, Islam ultimately proved to be a divisive influence in the volunteer battalions. Discipline was poor among the opportunists who followed the first wave of idealists to Abkhazia. It was mainly the sheer disorganization of the inexperienced Georgian paramilitaries that ensured their defeat in 1993. Nevertheless, it was the links established here that Basayev would call on to create his ‘Islamic Peacekeeping Army’ in 1999. By then many of the volunteers had picked up another two years of combat experience in the Russian/Chechen war of 1994-6. Shari’a law was introduced as a form of military discipline in the volunteer battalions; Islam added a religious motivation in fighting against the Georgian Christians as well as a means of unifying the disparate assembly of Mountain fighters.

When war between Chechnya and Russia broke out again in 1999 the KNK backed the Chechens, but were unable to offer anything more than moral support. Many members of the movement feared Chechen domination. Shanib’s Chechen successor as leader of the KNK, Yusup Soslambekov, was assassinated in Moscow in July 2000 (Soslambekov was a Chechen parliamentarian and early supporter of Chechnya’s first president, Dzhokar Dudayev).

Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev

Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev

With Russian forces on the attack in Chechnya, leading KNK member Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev maintained that “all the Moslem countries should participate in the Chechen jihad, rendering it both military and humanitarian support.” (al-Jazeera TV, July 6, 2000)

By 2002 Yandarbiyev had abandoned the Pan-Caucasus ideology for more specific aspirations; “Our aim is Chechnya as an independent Islamic state”. (Zerkalo [Baku], September 24, 2002) After leaving the KNK, Yandarbiyev’s assessment of the group was critical; “At the time of the Georgian-Abkhazian conflict the Confederation was ruled by (Yusup) Soslambekov, (Musa) Shanibov, and other people, who worked under the direct supervision of the Russian special services… We all know that unfortunately the Russian special services directed this organization from the very beginning” (Georgian Times, January 28, 2003). After briefly serving as Dudayev’s successor as president of Chechnya, Yandarbiyev was assassinated by Russian agents in Qatar in 2004 where he had been involved in fund-raising for the Islamist element of the Chechen resistance.

Both the Pan-Caucasus and the Islamist movements in the North Caucasus have always had to contend with nationalist movements that reinforce ethnic divisions rather than promote unity. Such divisions are unsurprising in a region experiencing mass deportations under Soviet rule and the subsequent re-assignment of land belonging to deported groups. The irredentist flavour of many of these national movements inevitably brings them into conflict with their neighbours. In Dagestan alone there is a broad range of nationalist groups, such as the Lak ‘Kazi-Kumukh’ or ‘Tsubars’, the Lezgin ‘Sadval’, the Dargin ‘Tsadesh’, the Nogay ‘Birlik’, the Kumyk ‘Tenglit’, the Avar ‘Union of Avar Jama’at’, etc.

Dagestani Origins of the Military Jama’ats

A jama’at is simply a communal organization designed to enable the pursuit of an Islamic lifestyle. They are found in many parts of the world and most are entirely peaceful organizations. In Dagestan, the formation of mountain jama’ats with economic and political functions followed closely on the Islamization of the region.

The Dagestani jama’ats of the 18th and 19th centuries were largely self-sufficient and were typically based on a single ethnic group. The jama’ats gradually took a role as protectors of community land against incursions from neighbouring jama’ats or other ethnic groups. In this way they developed a limited defensive military role. In times of extreme crisis the jama’ats could create alliances against a common threat.

The model for the modern North Caucasus military jama’at is found in Dagestan’s 1990s ‘Muslim Jama’at’, led by its Amir, Bagauddin Magomedov (aka Bagauddin Kebedov, an ethnic Khvarshin). Membership of the jama’at was mostly, but not exclusively, from the Dargin ethnic group. With at least thirty major ethnic groups and languages, ethnic tensions are never far from the surface in Dagestan. Peace and stability are ensured by a complicated political structure that reserves certain political offices for specific ethnic groups (much like Lebanon religiously-based system). Unfortunately the same system promotes stagnation, corruption and an almost complete reliance on federal subsidies.

Amir Ibn al-Khattab – right hand damaged by explosives

Amir Ibn al-Khattab – right hand damaged by explosives

The Muslim Jama’at a had two military leaders, Saudi jihadist Ibn al-Khattab (Samir Ibn-Salih Ibn ‘Abdallah al-Suwaylim) and Jarulla Rajbaddinov of Karamakh, the latter a self-styled ‘Brigadier General’ in command of the jama’at’s ‘Islamic Guard’. Al-Khattab, a veteran jihadist with experience in Tajikistan and the 1994-96 Russian/Chechen war, married locally but was often away in Chechnya, where he ran guerrilla-training camps in the interval between wars. The camps were attended by militants from across the North Caucasus.

Jama’at leader Bagauddin was one of the Dagestani leaders of the Islamic Revival Party (IRP), an early Islamist movement initiated in the late 1980s as the Soviet Union began to show signs of dissolution. In the early 1990s IRP demonstrations led by Bagauddin’s mentor, Abbas Kebedov, succeeded in driving Mufti Mahmud Gekkiyev from office (the Mufti was viewed as an agent of the old Soviet regime). By 1997 Bagauddin was leader of the newly formed Islamic Jama’at of Dagestan, a Salafist community dedicated to creating shari’a-ruled enclaves free of federal authority.

Bagauddin once declared ‘For us, geographic and state borders have no significance; we work and act in those places where it is possible for us to do so’. (Mikhail I Roshchin, ‘Dagestan and the War Next Door’, Institute for the Study of Conflict, Ideology and Policy, Perspective 11(1), September-October 2000) The Muslim Jama’at believed Dagestan’s government to be in a state of shirk (paganism). They strongly opposed the traditional Sufi lodges, believing that they violated the Salafists’ core doctrine of tawhid (monotheism) through the veneration of saints and pilgrimages to the tombs of holy men.

The Salafists, who soon became known as ‘Wahhabis’ (a pejorative in Russian use), centred their jama’at in the Buinaksk region of Dagestan. Previously obscure villages such as Karamakhi and Chabanmakhi became Salafist strongholds that attracted the presence of young Islamists from across Dagestan and further points in the North Caucasus. The presence of the veteran jihadist Ibn al-Khattab gave the jama’at a military dimension, with al-Khattab providing training to would-be mujahidin for what seemed an inevitable conflict with the Russian state. Volunteers received basic Islamic instruction that had to be mastered before the candidate could begin military training. A library was available, featuring works by Islamic reformers such as Indian/Pakistani Abu Ala Maududi, Egyptian Muslim Brothers Hassan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb, and Magomed Tagaev.

A Dagestani Avar, Tagaev authored two influential Russian-language works calling for armed rebellion against Russian ‘occupation’; Our Struggle, or the Imam’s Army of Insurrection (Kiev, 1996), and Jihad, or How to Become Immortal (Baku, 1999). These works found great favour with the Salafist Islamists of Dagestan, who saw to their distribution throughout their communities. In 1999 Tagaev served as Minister of Information in the short-lived (and self-appointed) ‘Islamic Government of Dagestan’. Tagaev was eventually extradited from Azerbaijan in April 2004, and sentenced to 10 years in a hard-labour camp for his part in the Salafist uprising (Interfax, April 10, 2004).

The murder of the mufti of Dagestan, Sa’id Muhammad-Haji Abubakarov, by a radio-controlled mine in August 1998 was a turning point for the Salafist movement in Dagestan, which was immediately blamed for the assassination. The charge was never proved, and there were many other suspects, including Avar leader Gadji Makhachev, and fellow high ranking clerics. Even the then president Magomed Magomedov was accused of the murder in rallies organized by Khasavyurt mayor Saigidpasha Umakhanov in 2004. (IWPR, August 19, 2004)

Mufti Abubakarov was a critical opponent of the Salafists (referred to, pejoratively, as ‘Wahhabis’):

Their teaching is constructed on quicksand. They deny what our grandfathers and ancestors believed. Can we defile the graves of our ancestors simply because Wahhabis consider that there should not be gravestones in the cemeteries? In disputes they appeal to the authority of Imam Shamil, who created the Caucasus imamate, and Islamic state. Well, this is true, but Imam Shamil cited holy men, many of whom were sheikhs of Sufi orders and religious leaders. It is against them that the Wahhabis are arguing by affirming that the true Muslim does not need mentors since between him and Allah there should be no intermediaries (Moskovskie Novosti, 25 August 1998).

As a political foundation for his activities Basayev formed the Congress of the Peoples of Chechnya and Dagestan (co-chairmen Movladi Ugadov and Magomed Tagaev – Kommersant, Ag 5, 05), supported by the ‘Islamic Peacekeeping Brigade’ under the command of al-Khattab.

Following Russian attempts in 1999 to suppress the semi-autonomous ‘Wahhabite’ enclave, Chechen warlor Shamyl Basayev his Arab ally Ibn al-Khattab attacked northwest Dagestan with a mixed force variously referred to as the ‘Islamic Peacekeeping Army’ or the North Caucasus Liberation Army. The attacks failed in part because Dagestanis were accustomed to ghazawat (holy war) leaders or Imams coming from the Avar ethnic group. While the insurrection attracted numbers of Avar youths, neither Basayev nor al-Khattab fulfilled this basic condition for leadership. Certainly neither even pretended to religious leadership, admitting that they were warriors who had spent months trying to determine the Islamic authority for their incursion into Dagestan.

The over-ambitious declaration of the Islamic Republic of Dagestan met with steadfast opposition from most of Daghstan’s Muslims, who were not prepared to abandon their carefully balanced system of local government (which did indeed help preserve peace between the republic’s many ethnic groups) and the much-needed subsidies provided by the central government of the Russian Federation in favour of a Salafist-led Islamic state. Basayev’s attacks initially focused on the Botlikh Rayon of Dagestan, where the Andi population organized their own Sufi-based jama’ats to oppose the Islamists.

The jihadists’ subsequent penetration of the Novolaksky Rayon did not fare any better. The failure of the Dagestan population to join a popular uprising against Russian rule seems to have taken Basayev by surprise. Bagauddin Magomedev, Lak politician Nadir Kachilayev and Ibn al-Khattab had all assured Basayev that the Dagestanis were only waiting for a signal to join a general rebellion. In fact the Salafists’ verbal and sometimes physical assaults on the dominant Sufist brand of Islam and its followers in Dagestan had made the Islamists extremely unpopular. Bagauddin’s movement made conciliatory moves towards the traditional Sufi community in 1998 as the Salafists refocused on replacing state control with Islamic government, but it was too liitle, too late. A bitter rift ensued between Basayev and Bagauddin after the failure of the invasion, though Basayev’s differences with al-Khattab proved only temporary. While still mufti of Chechnya, the late Akhmad Kadyrov saw Russian hands behind the Salafist revival in Dagestan; “The Kremlin deliberately fostered ‘Wahhabism’ in the Caucasus, in order to divide Muslims and unleash yet another war–a religious war–there” (Jamestown Foundation Prism, August 7, 1998).

Islamic Basis of the Jama’ats

The Islamic nature of the military jama’ats is unquestionable. Much of their effort is taken up with verbal or even physical assaults on the ‘hypocritical’ local leaders of ‘official Islam’. The spiritual boards responsible for Islamic activities in the Russian Federation were notorious in the Soviet era for including large numbers of KGB or GRU agents and informers. Suspicions linger to this day, and the spiritual boards are often regarded as being far too close to the regimes they serve. In August 2004 the ‘Mujahidin of Dagestan’ declared that “the position of the so-called ‘clerical department of Dagestan’ is anti-Islamic. This is a structural organization of Russian secret services, working for Moscow, against their fellow people and against Muslims. Its main mission is to provoke strife and discord among the nations of the Caucasus” (Kavkaz Center, August 14, 2004). A statement from the Shari’a Jama’at, for example, warned the Dagestani “spiritual board” (the administrative structure for official Islam) “to either shut their mouths or we would shut them for them and bury them” (Kavkaz Center, August 3, 2006).

The political opening brought on by the collapse of the Soviet Union allowed religious students the first opportunity in decades to study at Islamic schools in Egypt and Saudi Arabia. The severe and ostensibly authentic version of Islam encountered by Caucasian religious students in Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states contrasted with the rich traditions of Caucasian Sufist Islam, which soon came under fire from the Salafists for its numerous innovations (shirk) based on local customs rather than ‘authentic’ Islam.

The Jama’ats are mainly Salafist, although there are occasional efforts to incorporate Sufist Muslims into the communities. Bagauddin Magomedov’s Salafist jama’at made the mistake of constantly attacking the Sufi tariqats, creating much needless opposition within Dagestan. The current jama’ats tend to be more inclusive. Much of the appeal of Salafism is economically based in the Caucasus. The austerity of Salafism and its opposition to the extravagant and often ruinous ceremonies accompanying local occasions like funerals and marriages had an immediate appeal following the economic collapse of the 1990s.

The military jama’ats have made a point of broadening their ethnic base, rather than incorporating members of only a single ethnic type. The Kabardino-Balkarian Republic’s (KBR) Yarmuk Jama’at, for instance, has issued statements rejecting its depiction as ‘a monoethnic [Balkar] organization’, emphasizing the membership and even leadership roles of Kabardins in the jama’at. (Utro.ru, February 4, 2003) The North Caucasus Sufi lodges tend to have a more homogenous ethnic base than the Salafist jama’ats, which are open to a broader membership. Islam in the jama’ats tends to focus on the principle of tawhid (the unity of God) without the intercession of shaykhs or saints.

An important element of any Islamic insurgency is whether participation is individually obligatory (fard ‘ayn) for all Muslims, as opposed to a community obligation (fard kifayah), i.e., one that is met by the participation of traditional armed forces belonging to a Muslim state. Modern Islamist ideologues such as the Egyptian Muslim Brother Sayyid Qutb and the Palestinian founder of al-Qaeda ‘Abdullah ‘Azzam took a hard line on interpreting this question, with ‘Azzam going so far as to insist that jihad is fard ‘ayn until every piece of land that was once under Muslim rule is retaken.

With reference to the situation in their republic, the KBR’s Yarmuk Jama’at cited the three conditions under which jihad becomes mandatory (fard ‘ayn) under the Hanafite school of Islamic law followed in the northwest Caucasus:

1/ At the moment of invasion our nations were Muslim and were attacked by infidels

2/ Our lands were Muslim and were invaded by infidels (Kafirs);

3/ Shari’ah was the ruling law, the Law of Almighty Allah, and it was abolished by the invaders

Dagestan’s Shari’ah Jama’at has likewise insisted on the compulsory nature of resistance to Russian rule; “Jihad in the Caucasus is obligatory so long as the infidels continue to occupy an acre of Muslim land. It is obligatory to all, including men and women. During the time of the Imam Shamil, when there were not enough troops, the women took up arms to defend their villages, as happened in the battle of Akhulgo [the Dagestan site of an 80 day Russian siege in 1839]” (Kavkaz Centre, August 3, 2006).

Dagestan’s Shari’a Jama’at has suggested a change in the motivation in the young men who seek to join the mujahidin in the last decade: “Whereas before in the camps of Khattab near Serzhen-Yurt [1997-98], some people came out of curiosity and the desire to acquire Islamic knowledge, today young people dream of becoming martyrs on God’s path. And that means the time has come – the time of a Jihad and the victory of Islam” (Kavkaz Center, August 8, 2006). The jama’at also notes that the new generation of Muslims has the advantage of not having been indoctrinated in the Soviet ‘jahiliya’ (state of ignorance), thus leaving their minds open to the message of Islam.

Immediately following the Basayev/Khattab incursion into Dagestan, many of the other North Caucasus republics began a campaign to root out and destroy all traces of ‘Wahhabism’ in the region. Although the term ‘Wahhabi’ applies to followers of a specific Saudi Arabian Islamic reform movement founded in the 18th century, in the Russian context it covers a broad and often convenient spectrum of religious/political beliefs, at times applying to everyone from hard-core Salafist gunmen to those who simply attend the mosque on a regular basis. Though the number of Islamist militants in the northwest Caucasus was still extremely small in 1999-2000, rumours of an impending Islamist/’Wahhabist’ coup were promoted by local authorities. According to Khazretali Berdov, head of the Nalchik city administration:

Wahhabism in our republic [KBR] is by no means a horrifying myth. The Wahhabites work according to a well established plan: first, they infiltrate existing religious organizations, then they spark off confrontation between traditional Muslims and extremist factions. Finally they start shouting and screaming about the suppression of Islam in the Caucasus. (CRS no. 58, November 17, 2000)

Many jama’at members were arrested and brought to trial on all types of charges relating to armed insurrection and attempted overthrow of the state. The unfamiliarity of both state prosecutors and media with the jama’at structure at the time is reflected in the numerous references to ‘the terrorist organization called Jama’at’.

In a post-communist world of corruption and criminality the jama’ats assumed a communal security role that at times came into conflict with the police. The arbitrary brutality and torture allegedly practiced by state police in the Muslim republics gave the jama’ats a new purpose – revenge. Most of the jama’ats’ so-called ‘military operations’ across the North Caucasus are in fact part of a ruthless, no-quarter battle between police and those with experience of police violence. An example is the case of Gadzhi Abidov, his brother Shamil, and Sharaputdin Labazanov, who were tried for the murder of police Major Tagir Abdullayev in 2005. According to their testimony they committed the murder in revenge for torture inflicted by Major Abdullayev three months earlier. (Moscow Times, March 15, 2005).

Despite the militant nature of the new ‘military jama’ats’, leadership still tended to be drawn from Imams and local religious authorities. In the Stavropol region two Imams were convicted of organizing ‘a gun-toting Wahhabi gang’ that killed five policemen in 2002 before the group was broken up. (ITAR-TASS, October 27, 2004) Here again, Basayev used connections established in 1999 to help raise the ‘Nogai Battalion’ under the leadership of three brothers who had accompanied Basayev on his invasion of Dagestan, Ulubey, Kambiy and Takhir Yelgushiyev. Takhir was killed in 2002 and Ulubey was killed while allegedly planning a major operation under Basayev’s direction in Kizlyar in August 2004. (Vremye Novostei, August 2, 2004)

Shamyl Basayev: Organizing the Resistance

Though the Basayev/Khattab invasion of Dagestan will be remembered as a stunning miscalculation that played into the hands of the ‘hawks’ in the Kremlin, the connections Basayev made with the militant volunteers of the ‘Islamic Peacekeeping Army’ would later serve as the basis for Chechen attempts to broaden their war against Russia by creating new fronts across the northern Caucasus. The fierce fighting against the Russian Army separated the wheat from the chaff in the Islamist rebellion. Bagauddin, Siraj al-Din Ramazanov (Prime Minister of the ‘Islamic State of Dagestan) and Nadir Kachiliyev proved to be fighting a word of words, but the men who stood firm with Basayev formed strong bonds that could be called upon in the future.

ChRI President Aslan Maskhadov (left) and his successor, Abdul Halim Sadulayev

ChRI President Aslan Maskhadov (left) and his successor, Abdul Halim Sadulayev

The late president of Chechnya, Shaykh Abdul-Halim Sadulayev, described the North Caucasus expansion of the Chechen war as part of a plan intended to extend until 2010 (Chechnya Weekly, July 6 2006). The scheme was adopted at the 2002 Majlis al-Shura meeting during the presidency of the late Aslan Maskhadov. As both a military veteran and a religious leader (though his authority in this area was challenged by his enemies), Shaykh Abdul-Halim seemed to Basayev and others an ideal candidate for the role of Imam of the North Caucasus. Following in the tradition of Shaykh Mansur and Imam Shamyl, Sadulayev would lead the region’s Muslims in a general uprising against infidel rule (at least in theory), and Basayev was quick to arrange an oath-taking of personal loyalty to Sadulayev by the leaders of the various Caucasian jama’ats. Sadulayev claimed the existence of jama’ats composed of ethnic Russians in the Russian republic that had pledged their loyalty to him as Amir of the Majlis al-Shura. (Chechnya Weekly, July 6 2006) The Shaykh also announced the creation of a new ‘Caucasian Front’ incorporating Ingushetia, Ossetia, Stavropol, the KBR, the Karachaevo-Cherkessian Republic (KCR), Adyghei and Krasnoyarsk before the entire programme crashed to a halt with Sadulayev’s death at the hands of federal forces in June 2006.

Surviving Basayev’s Death

Though the Chechen resistance may be reluctant to admit it, Basayev’s death was a major blow to creation of the ‘Caucasian Front’. The defiant reaction of Dokku Umarov (current ChRI president) to Basayev’s death was to announce the creation of two new sectors in the larger ‘Caucasus Front’. The statement creating a Ural Front and a Volga Front amounted to declaring an expansion of the war to the Russian republic. The Volga Front was placed under the command of Amir Jundulla, while the Ural Front is led by Amir Assadulla, a former member of the ‘Ingush mujahidin’ and a leading participant in the 2004 raid on Nazran.

Should a negotiated settlement be reached at some point between the representatives of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria and the Russian Federation it is difficult to see how the jama’ats would fit into such an agreement. Would the orphaned Jama’ats revert to independent activities under local leadership or would they gradually dissolve under the weight of Russian security forces freed from deployment in Chechnya? (see Mayrbek Vachagaev, Chechnya Weekly, August 3, 2006). The recent and controversial ‘Manifesto for Peace in Chechnya’ presented by ChRI Foreign Minister Akhmed Zakayev after the death of Shamyl Basayev made no mention of the jama’ats. In an August 2006 statement meant to refute the damage caused to the Jama’at movement by Basayev’s death and to establish the continuing viability of their organization, the ‘Military Command of the Ingush Center of the Caucasian Front’.presented a lengthy list of military operations carried out since Basayev’s death on July 10, 2006 (Kavkaz Center, August 29, 2006).

The growth of the locally based military Jama’ats has been concurrent with the declining importance of the foreign mujahidin led by Jordanian Abu Hafs. The Arab jihadists have found more accommodating territory (in a cultural, linguistic and even climatic sense) for the pursuit of their struggle in Iraq, part of a general abandonment of the Chechen cause in the Arab world. Abu Hafs al-Urdani has commanded the international mujahidin since the death of Saudi Amir Abu al-Walid (‘Abd al-Aziz al-Ghamidi) in April 2004. Though precise numbers are hard to come by, at this point foreign jihadis are not likely to amount to more than a few score members, with Turks probably as well represented as Arabs.

A Moral Revolution

The Jama’ats routinely assail the corruption and lax moral standards of the region’s rulers. The trade in narcotics, the existence of prostitution, the use of alcohol and a general moral decay are all laid at the door of the official power structures. The Yarmuk Jama’at detailed their objections to conditions in the KBR in their August 2004 founding statement:

We are fighting against tyrants and bloodsuckers, who put the interests of their mafia clans above the interest of their nations. We are fighting against those who get fat at the expense of the impoverished and intimidated people of Kabardino-Balkaria, whom they brought down to their knees… These mere apologies for rulers, who sold themselves to the invaders, have made drug addiction, prostitution, poverty, crime, depravity, drunkenness and unemployment prosper in our Republic. It is their corrupt policies that undressed our daughters and our sisters and brought them to lechery and permissiveness… On their orders Muslims of Kabardino-Balkaria get kidnapped and tortured. On their orders our mosques are getting closed down. (Kavkaz Center, August 24, 2004)

Bagauddin Magomedov favoured the creation of a force of moral police (muhtabisin) to enforce the observance of shari’ah law in daily life. (Statement of July 1997, quoted in; Mikhail I Roshchin, “Dagestan and the War Next Door,” Institute for the Study of Conflict, Ideology and Policy, Perspective 11(1), September-October 2000). Armed Salafists created their own system of law enforcement in northwest Dagestan in 1997-98, driving criminal elements and drug dealers from their villages.

The Nalchik Narcotics Control Department raid in December 2004 is the outstanding example of the use of arms by the jama’ats to correct immoral conduct. The department as a group was accused of running the local illegal drug trade and in the ruthless attack no attempt was made to ascertain the individual responsibility of those police present for these alleged crimes. Some consolation for was offered by a leading KBR mujahid for honest police officers who fell in mujahidin assaults:

We know that among government officials there are many people who did not join the law enforcement bodies and other state government structures to rob the people. They work in good faith, combat crime, the drug business and corruption. There are many Muslims among them, who observe religious requirements fully or partially. If these types of people suffer from our actions this will happen only because we don onot know them and cannot distinguish them from atheists and corrupt people. If they suffer by mistake, they will be recompensed for this on Judgment Day, and if they get killed, they will become martyrs, if they are true believers… (Kavkaz Center, March 25, 2005).

Operations of the Military Jama’ats: Dagestan

Considering the origin of the military jama’ats, it should be unsurprising that Dagestan is today the home of the most active of all these organizations. For some years now Makhachkala has been a virtual battleground. In Dagestan the rebels are less likely to be found in the mountains than in the cities, with the urban warfare of assassinations, bombings and gunfights replacing the tactics of a mobile guerrilla force. The fighters have even renamed Makhachkala ‘Shamilkala’, after the great 19th century Dagestani Imam and rebel leader Imam Shamyl.

Support for the jama’ats is far from universal. Many in Dagestan regard Russian rule as the only thing that prevents the region from exploding into a multi-sided civil war. While corruption is endemic in Dagestan (like the other North Caucasus republics), ethnic imbalance in access to the proceeds of corruption generally tends to be more provocative than Islamic or separatist motivations in sparking opposition to the government.

Like its counterparts in the North Caucasus, Dagestan’s Shari’a Jama’at has concerns that go far beyond religious revival. The group points out the poor educational level of the Dagestani leadership, their proclivity for corruption, and the prevalence of nepotism. The republic’s leaders are characterized as “intellectually and morally backward riff-raff” and an “unmanageable rabble or ignoramuses and half-wits”. (Kavkaz Center, July 31, 2006) The difficulty of progressing through the clan-based power structure has persuaded many educated young Dagestanis to leave the republic, an issue the jama’at also addressed in a response to government claims that the rebel Muslims lacked the intellectual abilities and administrative skills to form a government;

Among the Muslims there are many educated people and brothers who are honest and care about God’s religion. They include doctors, engineers, teachers, psychologists, managers and builders, economists and businessmen. By mobilizing the intellectual potential of Muslim youth, we shall be able to effectively run the economy and the state. The brothers who are today studying in higher educational establishments, and not just Islamic ones, will be involved in building an Islamic state. (Kavkaz Centre, July 31, 2006)

The Shari’a Jama’at has also taken a strong position against the activities of the Spiritual Board of Muslims in Dagestan (SBMD), an Avar dominated directorate headed by Sa’id Effendi of Chirkey (Avars are the largest ethnic group in Dagestan). The SBMD is responsible for the operation of the republic’s officially registered mosques, and vehemently opposes the existence of all unauthorized expressions of Islamic faith. The Board has been responsible for a number of seemingly provocative decisions, such as the May 2004 ban on the distribution of Russian translations of the Koran (despite Dagestan’s historic ties to Arab Islam, few in the republic can now read the Koran in its original Arabic). (Caucasian Knot, May 24, 2004) The Shari’a Jama’at has warned that those involved in replacing the Imams of Dagestani mosques on political grounds will face ‘severe punishments’.

Rappani Khalilov (center) with Shaykh Abdul-Halim Sadulayev (left) and Abu Hafs al-Urduni.

Rappani Khalilov (center) with Shaykh Abdul-Halim Sadulayev (left) and Abu Hafs al-Urduni.

Much of the insurgent acitivity in Dagestan appears to be directed by Lak guerrilla leader Rappani Khalilov, a dangerous and experienced field commander, tightly integrated to the Chechen forces, and a former close ally of Shamyl Basayev. Khalilov is Amir of the Dagestani Front of the ChRI Armed Forces and is alleged to control the activities of the Dagestani jama’ats, though this is difficult to confirm. Khalilov appears to spend much of his time in eastern Chechnya (a group of his men was spotted there recently – Interfax, September 7, 2006). A veteran of the Russian army, Khalilov was a brother-in-law of Arab mujahidin leader al-Khattab and participated in the 1999 attack on Dagestan. After a period in Chechnya Khalilov took the fight back to Dagestan in March 2001, launching a wave of attacks. (Gazeta.Ru, May 21, 2003) Khalilov was blamed for the May 9, 2002 bombing of a military parade in Kaspiisk that killed 45 and wounded 170.

Rasul Makasharipov

Rasul Makasharipov

Rasul Makasharipov was the first leader of the Shari’a Jama’at and the former leader of Dzhennet (Jenet – Arabic; ‘paradise’), a militant group that evolved into the Shari’a Jama’at. Like Khalilov, Makasharipov’s relationship with Basayev went back to the 1999 Dagestan incursion, when Makasharipov served as Basayev’s Avar interpreter. He surrendered to Dagestani authorities in 2000, but was released in an amnesty a year later. Within a year he was assembling his own organization, finding willing recruits from young Dagestanis who had suffered at the hands of the police. According to one of his followers, “Makasharipov spoke about the necessity to stop persecution and humiliation of Muslims in Dagestan. He said this could be done by killing policemen”. (Moscow Times, March 15, 2005) Good to his word, Makasharipov launched a vicious three year campaign of retribution against police officials. Operating mainly in the Makhachkala region, Shari’a hit squads have killed dozens of high-ranking police officers and investigators while fighting to the death when cornered. Hand-grenades, bombs, mines and small arms are the weapons of the jama’at’s campaign against the police.

The FSB reported the death of Makasharipov in a tank attack on a home in Makhachkala, January 15, 2005, although the jama’at commander surfaced four days later to refute these claims. Makasharipov was finally killed in a gunfight in Makhachkala on July 6, 2005. There are reports that after Makasharipov’s death the Shari’a Jama’at splintered into several smaller groups, though assassinations and bombings continued at the same pace. Gadzhi Melikov took over as Amir of the Makhachkala-based group that continues to use the name ‘Shari’a Jama’at’ until his own death in a spectacular firefight in the Dagestani capital on August 26, 2006.

The military jama’ats of the Caucasus are often divided into Special Operations Group at an operational level. Among the subdivisions of the Shari’a Jama’at are the Abuldzhabar Special Operations Group, the Asadulla Special Operations Group and the Mahdi Special Operations Group. The Riyadus al-Salikhin Special Operations Group (Shamyl Basayev’s ‘suicide battallion’) has also been reported as carrying out assassinations and other attacks on police. (Kavkaz Centre, August 21, 2006)

A leaflet entitled “Address to the police of Dagestan” and signed by ‘The Mujahidin of Dagestan’ appeals directly to the often poorly paid policemen of the republic:

We, the Mujahidin of Dagestan, are once again addressing the policemen of Dagestan, who still possess sound judgment. For a miserable sop from your oppressors, you are risking your own lives. We are calling you to quit this job and to not stand between us and the unlawful authorities of Dagestan, which are in power today… Your rulers want to retain their power over you at any cost. They are sacrificing your lives and putting you under our bullets… [The leaflet finishes with a distinctly Salafist invocation] Return to the religion of monotheism, pure from all admixtures of polytheism and all sorts of innovation. (Kavkaz Center, August 11, 2004)

Despite the ferocity of the battle between Islamists and police in Dagestan, it should not be interpreted as a sign of an incipient general uprising. The mujahidin of the Shari’a jama’at and the guerrilla band of Rappani Khalilov have not yet managed to rouse more than a tiny portion of the republic’s population to their cause.

Another active jama’at in Dagestan is the Khasavyurt Jama’at, formerly under Amir Islam Batsiyev until his capture in 2005. (Interfax, February 7, 2005) His successors, the Amirs Vagit Khasbulatov and Shamil Taimaskhanov, were killed October 2, 2005 in a wild shootout near Kizilyurt. (Kommersant, October 3, 2005) Chechen militants belonging to the Gudermes Jama’at have also been operating in the Khasavyurt region, according to Dagestani police (Itar-Tass, February 22, 2005).

Though there are many signs that Dagestan’s military jama’ats often receive information from collaborators within the security structure, constant pressure from the police may have led the jama’ats to split up into autonomous three-man cells, an effective means of resisting police infiltration or interrogation. (Nezavisimaya Gazeta, May 17, 2005) Dagestani president Mukhu Aliyev has alleged in the past that ‘traitors’ in the government were working closely with ‘the terrorists’. (NTVru.com, May 13, 2002)

Operations of the Military Jama’ats: Ingushetia

The ‘Ingush Jama’at’ may have its origins in the battle for the entrance to Chechnya’s Argun Gorge (known as the ‘Wolf’s Gates’) in 2000. Here a group of Ingush volunteers mounted a stubborn defense against the overwhelming force presented by Russian arms. According to Chechen sources, only seven fighters survived, each of whom became a leading member of the Ingush Jama’at (Chechenpress, June 23, 2004).

Magomet Yevloyev “Magus”

Magomet Yevloyev “Magus”

The Ingush Jama’at had a prominent role in the rebel raid on the Ingushetian city of Nazran in June 2004. According to pro-Russian Chechen president Alu Alkhanov (a former police general) Basayev’s Ingush deputy, Magomet Yevloyev (aka Ali Musaevich Taziev, aka ‘Amir Magas’), led the Nazran operation. Yevloyev was raised in Grozny and was a sub-commander under Basayev in the second Russian/Chechen war before Basayev assigned him to use family and clan ties to begin raising armed units in Ingushetia. (Interfax, June 28, 2004) Ilyas Gorchkanov, the Amir of the Ingush Jama’at, was killed in the October 2005 raid on Nalchik.

Aside from the participation of nearly 100 Ingush insurgents in the Chechen-led raid on Nazran, the Ingushetian rebellion is primarily one of ambushes and assassinations, largely against police and Interior Ministry units. Despite belonging to the same Vainakh ethnic group as the Chechens, rebellion in Ingushetia was slow to build, due to a prevailing atmosphere of loyalty to the Russian Federation. Political interference and growing severity on the part of state security forces in an apparent pre-emptive campaign against Islamist separatists eventually began to turn Ingushetia into one of the most active centers of resistance to federal rule. ChRI Foreign Minister Ahmad Zakayev described the situation in Ingushetia prior to the assault on Nazran:

It can be stated with certainty that the war in Ingushetia began already at the moment whenthe Kremlin forced President [Ruslan] Aushev to retire and installed its humble protégé [Murat] Zyazikov in his place, a Chekist cadre. From that time on, Ingushetia became a zone of the bloody trade of the Russian death squads. Murders, hostage-taking, terror against the Chechen refugees and complete lawlessness became a daily reality in Ingushetia… Finally, the indignation of the people reached a critical mass and took the form of a direct, armed riot. (Chechenpress, June 22, 2004)

Zyazikov, who has been the target of several assassination attempts since taking over the presidency, offered his own take on the Nazran raid:

This inhuman action was aimed not only against the Ingush people, but also against tens of thousands of Chechen refugees living in Ingushetia. Its objective was to destabilize the republic, expand the theater of military operations, and spread fear among the civilian population… The republic’s residents can be confident that any barbarous actions will be rebuffed in a resolute manner (Interfax, June 22, 2004).

In their July 24, 2004 declaration of a jihad to establish an Islamic state, the Military Council Majlis al-Shura of Ingushetia presented an optimistic assessment of Islamist aims in a deteriorating Russian Federation:

Weakness in domestic and foreign policies, a collapsing economy, desertion in the army, failure of reforms, administrative anarchy, lack of security, drug trafficking, AIDS, elimination of social morals compared to the strengthening of the Mujahidin and orderliness in the organization of combat operations speaks about changes and the future victory coming soon. False ideologies are collapsing; nations all around the world (including Russia) are focusing their eyes on Islam as the only source of true justice, law and safety from tyranny, abomination and ignorance. (Kavkaz Center, July 10, 2004)

Retribution by the police for the murder of their comrades in the Nazran raid began immediately. According to the Ingush Interior Ministry, 170 of the raiders have been eliminated. (Ingformburo, September 1, 2006) Ingush journalist Yakub Khadziyev has noted the pernicious influence of the North Caucasus custom of blood feud on the struggle between insurgents and police:

The members of illegal armed formations who are still at large are also not waiting for the security officers to come after them or for a bullet from someone settling a blood feud, but are waging a real struggle with the republic’s law-enforcement bodies. No-one knows how many years this struggle will go on for. The relatives of the dead and the detained from both sides are virtually taking part in a bloody feud of retribution against one another (Ingushetiya.ru, August 25, 2006).

In a similar fashion to some of the other North Caucasus republics, the conflict in Ingushetia has degenerated into a brutal contest between police and insurgents. The homes of policemen have been burned to the ground and security operatives of all types are constantly subject to assassination by gunmen. Ruthless interrogations of detainees too frequently provide the insurgency with new recruits after their release.

Also active in Ingushetia is the Khalif Jama’at, whose leader Alikhan Merjoev, (responsible for the Ingush sector of the Caucasian Front) was killed by FSB (Federal Security Service; former KGB) agents in Karabulak in October 2005.

Operations of the Military Jama’ats: Kabardino-Balkaria

The first major Islamic jama’at in the KBR was the Kabardino-Balkar Jama’at, led by Imam Musa Mukozhev and Anzor Astemirov. Mukozhev studied Islam in the Arab world and developed a large following in the KBR. The K-B Jama’at avoided militancy, devoting itself to the study of Islam and promoting freedom of worship. After Basayev’s disastrous terrorist operation in Beslan in September, 2004, the jama’at came under pressure to dissolve from the police. Accused of participation in the December 2004 raid on the Federal Drug Control Service in Nalchik, Astemirov threw in his lot with Basayev. Both Mukozhev and Astemirov were close associates of Ruslan Nakhushev, the head of the Islamic Studies Institue in Nalchik. Nakhusev disappeared after reporting to FSB headquarters in connection with the Nalchik raid. He was charged in absentia a week later with terrorist activity.

Anzor Astemirov

Anzor Astemirov

The KBR’s Yarmuk Jama’at was founded by Muslim Atayev (AKA Amir Se’ifulla), a Balkar veteran of the Pankisi Gorge training camps in Georgia. Atayev led a group of 20-30 KBR volunteers in the Ruslan Gelayev-led field force that crossed back into the North Caucasus republics in the autumn of 2002. After fighting in Ingushetia, Atayev led the KBR guerrillas back into their home republic, creating the ‘Kabardino-Balkarian Islamic Jama’at ‘Yarmuk’’ in August 2004 as a local independent militant operational group. The jama’at’s founding statement cited government closure of mosques and interference in Islamic practices as core reasons for their embrace of jihad. (Kavkaz Center, August 31, 2004)

The KBR police (who are mostly Kabardins) took the threat seriously. The head of the religious extremism unit (a frequent target of the fighters) suggested, “Yarmuk presents a real threat to the security of the people of the republic. Members of this jama’at are experienced fighters who have undergone special technical and psychological preparation in order to carry out subversive activities.” (CRS no.255, September 29, 2004) Basayev was nearly killed in the KBR town of Baksan on an organizing tour when his presence was detected in a house. The building was assaulted and a policeman killed before a wounded rebel blew himself up with a grenade, enabling Basayev and his companions to escape in the chaos. In December 2004 the jama’at struck the Federal Drug Control Service in Nalchik, shooting several narcotics officers it described as ‘drug dealers’ and seizing a large quantity of arms. The jama’at stated that the officers had been killed according to Sharia’ law, which prescribes the death penalty for dealing in narcotics. (Kavkaz Center, December 14, 2004) Amir Atayev and several comrades were killed not long after in a spectacular January 2005 urban gun-battle after being cornered by police in a Nalchik apartment building.

Anzor Astemirov was the successor to Atayev as chief of the Yarmuk Jama’at. Astemirov was the director of the Institue for the Study of Islam and a student of Dagestani Salafist preacher Ahmad-Kadi Akhtaev (poisoned, 1998).

The sudden appearance of hundreds of armed gunmen on the streets of the KBR capital of Nalchik on a quiet morning in October 2005 took the republic and the Kremlin by surprise. Throughout the city bands of insurgents attacked police stations, government offices and the local FSB headquarters. The raid was planned by Basayev and directed by Yarmuk leader Astemirov. Surprisingly the insurgents were Balkar and Kabardin in nearly equal numbers, demonstrating that political/religious repression combined with clan politics was capable of bringing armed rebels into the street.

Although the jama’at developed in the Balkar villages of the mountains, their statements avoid any hint of Balkar nationalism in favour of appeal for ethnic unity amongst Muslims. A January 2005 statement mentions the 19th century colonization and subsequent expulsion of much of the population of ‘Kabarda, Balkaria, Karachai, Cherkessia and Adygea’, reminding these groups of a common experience and common grievance. (Kavkaz Center, January 21, 2005)

The Yarmuk Jama’at remains active; a fierce gun battle between armed members of the jama’at and federal security forces was reported in a forested area just outside of Nalchik following the discovery of a rebel base on August 12. (Interfax, ITAR-TASS, August 12, 2006)The jama’at is now part of the Kabardino-Balkar sector of the Caucasus Front. (Chechenpress.org, October 17, 2005)

Operations of the Military Jama’ats: Karachaevo-Cherkessia

According to the reports of the security forces, the leading group of Salafist militants operating in the Karachaevo-Cherkessian Republic (KCR) is the Karachai Jama’at, also known as ‘Muslim Association No. 3’. The group is allegedly led by Achimez Gochiyayev, a self-described ‘patsy’ in the 1999 apartment building bombings in Moscow and a fugitive from federal authorities ever since. Gochiyayev was accused of working with Salafist Imam Ramzan Burlakov to create Islamic jama’ats in the KCR during 1996-99, a period Gochiyayev claims he spent in Moscow doing business. (Moscow News, June 23, 2002) Despite occasional messages from Gochiyayev in which he denies having anything to do with the North Caucasus insurgency, Russian security forces maintain that Gochiyayev is an elusive terrorist mastermind responsible for a series of bombings and terrorist attacks in Moscow as well as the Caucasus.

Dozens of jama’at members in the northwest Caucasus were prosecuted behind closed doors in 2002 in relation to a series of car bombings and an alleged plot to overthrow the KCR and KBR governments in the summer of 2001. Although even security officials questioned the likelihood of a small number of lightly armed militants mounting a successful coup, the roundup was proclaimed a triumph for ‘anti-Wahhabist’ counter-terrorism efforts. The alleged ringleaders were Khyzyr Salpagarov and the brothers Aslan and Ruslan Bekkaev (Isvestia.ru, May 12, 2002). Salpagarov was an Imam and Amir of the KCR’s Ust-Djeguta Jama’at. His eventual testimony described a wide plot engineered by Shamyl Basayev, al-Khattab and Ruslan Gelayev. Salpagarov was alleged to have attended one of al-Khattab’s training camps in Chechnya in 1998 before returning to the KCR to initiate jihad operations (Moscow News, June 23, 2002).

The Imam was convicted and sentenced to 19 years and confiscation of property for ‘preparing an armed uprising’. The details of the conspiracy did not seem to concern the KCR president, General Vladimir Semenov (a Karachai):

When I heard how the whole country is being told about an attempted coup d’état in Karachai-Cherkessia, I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. What coup, what nursery of Wahhabism? We were among the first in Russia to ban religious and political extremism. I can’t say that we have absolutely no Wahhabis, but the population has a single view on this, they reject it (CRS no.152, October 24, 2002).

Islamic insurgency in the KCR is usually associated with the Turkic Karachai people. The Hizb al-Tawhid Jama’at is almost exclusively Karachai. In 2002 its Amir, Dagir Bejiev, described the importance of Salafist preacher Ramzan Burlakov bringing Karachais to jihad; ‘Today over a thousand of the best sons of the Karachai Nation are participating ias much as it is within their capabilities in the process of the revival of Islam, at their home as well as across the entire Caucasus. Ramzan was the initiator of this revival’. (Radio Kavkaz, July 17, 2002) Burlakov is reported to have led 150 Karachai mujahidin to Chechnya in the early days of the second Russian/Chechen war, where he was killed in combat.

The KCR Interior Minstry estimates there are at least 200 radical Islamists in the republic prepared to take arms against the government. Insurgents tend to travel freely between the KCR and the neighbouring KBR.

Operations of the Military Jama’ats: North Ossetia

Despite the continuing violence in North Ossetia (much of which carries undertones of Ossetian-Ingush ethnic rivalry and disputes over land), the local FSB directorate has denied the very existence of an ‘Ossetian Jama’at’. (Caucasus Times, August 4, 2006) Responsibility for assassinations and attacks on police in North Ossetia is regularly attributed by Chechen websites to a local group known as the Kataib al-Khoul Jama’at and its ‘Sunzha’ Special Operations Group.

A statement from the Kataib al-Khoul Jama’at taking claim for the destruction of a Russian armoured personnel carrier (APC) described the type of local knowledge and access to inside information that enables the jama’ats to operate; “The Mujahideen of the Kataib al-Khoul Jamaat know all the dislocation areas, stationary and mobile posts as well as all the secrets used by Russians and traitors in the border area between Ossetia and Ingushetia and the routes of military convoys… We have flight charts of the aviation deployed in Ossetia, we know all the airfields of military airplanes and helicopters. Allah willing, already this year Ossetia will cease being a safe airspace for (the Russians)”. (Kavkaz Centre, September 7, 2006)

Conclusion

Abdul-Halim Sadulayev observed that the North Caucasus jama’ats shared with the Chechens “one common goal – liberation from colonial slavery and achieving freedom and independence. Like the Chechen people, all the peoples around us have risen up and want freedom and independence.” (Chechnya Weekly, July 6 2006)

Some jama’ats are now describing themselves as regional units of the Caucasus Front, using names such as ‘Mujahidin of the Caucasian Front of the CRI Armed Forces’, suggesting a greater integration with the Chechen command. Regardless of conditions in the North Caucasus republics, the jama’ats and associated militant groups enjoy the active support of only a minority of the population. Many Muslims have made clear that the militants do not speak in their name. Despite the Islamic basis of the Jama’ats, their activities and membership are still subject to ethnic, territorial and economic considerations. The Sufi tariqats still hold the allegiance of most North Caucasus Muslims, even in Dagestan.

In the last year the jama’ats have not displayed any ability to mount coordinated attacks that would test the response abilities of federal armed forces. This is no doubt due to difficulties in communication between armed groups justifiably wary of electronic communications. Basayev’s great talent was his ability to travel throughout the North Caucasus, organizing the resistance, planning attacks, and providing a link to the ChRI military command. The warlord used sympathizers in the security services and exploited the corruption that prevailed in government structures to enable his safe passage through checkpoints, though he was constantly in danger of exposure.

Pro-Russian Chechen President Alu Alkhanov recently estimated that there are only 500 guerrillas still operating in the North Caucasus. (Interfax-AVN, August 3, 2006) Indeed, Ramzan Kadyrov has proclaimed that 2006 “is the last year of bandits in Chechnya”. (Interfax, July 31, 2006) The Jama’ats typically claim that their ranks are increasing to the point where many would-be mujahidin have to be turned away. FSB chief Patrushev seemed to confirm this possibility when he stated that rebel attacks in Ingushetia and North Ossetia during the period January to July 2006 had increased by 50% over the same period last year.

Federal and Republic authorities have had great hopes for the amnesty announced for political militants this summer. Chechen Deputy Prime Minister Adam Demilkhanov recently claimed that only 50 mujahidin and 30 foreign-born ‘mercenaries’ were still active in the republic (Interfax, August 29, 2006). According to FSB director Nikolai Patrushev, 224 insurgents have answered the call to surrender since the amnesty program was put into place on July 1, 2006. (Ekho Movsky, September 5, 2006) The amnesty campaign has been extended until the end of September 2006. Efforts are being made to tie the amnesty to job creation programmes, without which the ex-mujahidin might once more ‘go to the forest’.

Besides creating new fronts for jama’at activity in the Caucasus, the Chechen armed forces have signaled that they are prepared to operate beyond the traditional Russian boundaries of the conflict prescribed by Maskhadov and Basayev. On June 8 the State Defence Council of the Majlis al-Shura council announced that it had given operative powers to President Dokku Umarov to authorize Chechen operations abroad to eliminate those sentenced to death by the Shari’ah courts for participation in what the council refers to as the ‘genocide of the Chechen people’. The task was assigned to the Chechen Special Services under the direction of the ChRI Department of Special Operations.

While the military jama’ats remain a virtually impenetrable and highly flexible source of instability in the North Caucasus, they by no means represent a legitimate challenge to the Russian armed forces. Attacks on police occur on a regular basis, but there has been no major raid or insurgent campaign since last year’s events in Nalchik. Losses in police ranks are easily replaced in a region with dramatically high levels of unemployment, like the North Caucasus. The real question is whether a war against the police constitutes a revolution? The jama’ats have not been able to relieve pressure on the Chechen mujahidin, as was intended by the creation of new fronts, nor are they any closer to achieving their aim of an Islamic state in the North Caucasus, despite their embrace of pan-Caucasianism.

This article first appeared in Glen E. Howard (ed.), Volatile Borderland: Russian and the North Caucasus, Jamestown Foundation, Washington D.C., 2011, pp. 237-264.

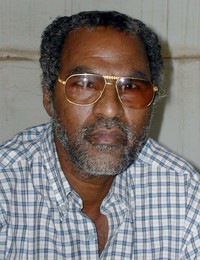

Russian Interior Minister Colonel-General Rashid Gumarovich Nurgaliyev

Russian Interior Minister Colonel-General Rashid Gumarovich Nurgaliyev