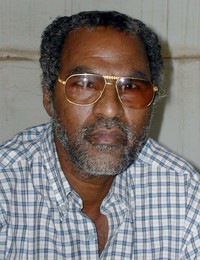

Andrew McGregor

September 19, 2006

The brutal decapitation of Khartoum newspaper editor Muhammad Taha earlier this month was part of a much larger inter-Islamic struggle reaching from the mountains of northwest Pakistan through Darfur, Tunisia, Paris and London. The murder took place against a local backdrop of street clashes between demonstrators and riot police, growing press censorship and calls from Sudan’s president Omar al-Bashir for national unity against the “threat” of UN intervention in Darfur.

On the evening of September 5, 50-year-old Muhammad Taha, editor of the Islamist daily al-Wifaq, was abducted from his home by three masked assailants. His body was found in the street the next day, bound and beheaded. Taha was a member of the Sudanese Ikhwan (Muslim Brotherhood), a former member of Hassan al-Turabi’s National Islamic Front and traditionally regarded as a friend of the military/Islamist regime. Taha’s relationship with the government was actually much rockier, tested by Taha’s fondness for provocative viewpoints in both the political and religious spheres. In 2000, he survived an assassination attempt after criticizing the ruling National Congress Party, and six months ago arsonists struck al-Wifaq’s offices.

Responsibility for the shocking murder was claimed in an internet statement by Abu Hafs al-Sudani, who purported to lead al-Qaeda in Sudan and Africa (al-Arabiya, September 12). Both the individual and the organization were previously unknown. The name appears to be a variant of a name commonly used by other well-known Islamic militants, such as Abu Hafs al-Misri, Abu Hafs al-Mauritani and Abu Hafs al-Urdani. In the statement, Abu Hafs accused the editor of dishonoring the Prophet, but also referred to Taha as “a dog of dogs from the ruling party.” Abu Hafs said that the killers were safely outside of Sudan, perhaps accounting for the delay in claiming responsibility. Khartoum senior prosecutor Babekir Abdelatif downplayed the possibility of al-Qaeda involvement on September 13 (Sudan Tribune, September 13).

Politicians such as Umma Party leader Mubarak al-Fadil have suggested the al-Qaeda claim was meant to deflect attention from local Sudanese Islamists. The murder would represent al-Qaeda’s first activity in Sudan since Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri urged their followers to attack UN forces in Darfur in an April 23 statement broadcast by al-Jazeera television.

The charges of “dishonoring the Prophet” stem from an obscure anti-Islamic tract serialized in Taha’s newspaper accompanied by commentary by Taha. As the excerpts appeared, al-Wifaq‘s offices were targeted by demonstrations by the Islamist group Ansar al-Sunna. Taha was charged with the capital offense of blasphemy shortly after the articles appeared. Protestors gathered outside the courtroom daily demanding that prosecutors hand over Taha so that he could be killed immediately. In the end, Taha was fined US$ 3,200 and al-Wifaq was shut down for three months. After his trial, Taha continued to irritate the government through criticism of their Darfur policy and price hikes in staples designed to cover a budget shortfall.

Most media accounts of the publishing controversy and Taha’s subsequent death incorrectly maintain that the offensive work in question was authored by the famous 15th century Egyptian historian al-Maqrizi. In fact, it is a recent pro-Christian, anti-Islamic tract entitled al-Majhool fi Hayat al-Rasool (The Unknown in the Life of the Prophet), a poorly researched work whose author uses the pseudonym “Dr. Maqrizi.” The full text was made available at www.alkalema.us, a Christian Arabic website.

The first chapter serialized by al-Wifaq claims that the name of the Prophet’s father was not Abdullah, but Abd al-Lat (Lat was an Arabian pagan god) and suggests that Muhammad was ineligible by his lineage to be a Prophet. During his trial, Taha maintained that his intent in serializing the work and his accompanying commentary was to refute the claims of “Dr. Maqrizi,” describing the charges as “a joke” and politically motivated.

In the meantime, a Tunisian Islamist accused 72-year-old Paris-based Tunisian intellectual al-Afif al-Akhdar of being the anonymous “Dr. Maqrizi.” Rached Gannouchi, leader of the Islamist Harakat al-Nahda group, used the organization’s website (nahdha.net) to accuse al-Akhdar of writing the tract, reveling in his physical disabilities (“punishment from God for heresy”) and issuing a fatwa calling for al-Akhdar’s death for the offense of blasphemy. The book’s claim that the Prophet was guided by Satan and assertions of the superiority of Christianity over Islam in no way resembled al-Akhdar’s well-known intellectual and rationalist approach to Islam, a religion to which al-Akhdar remains deeply attached. Gannouchi issued his call for murder from the safety of British asylum, leaving al-Akhdar to appeal to the British justice system for Gannouchi’s prosecution. The imam was eventually compelled to withdraw the baseless accusations from the website.

The cause for Gannouchi’s scurrilous attack was evident. In October 2004, al-Akhdar joined two other Arab intellectuals in petitioning the UN Security Council to create an international court capable of trying Islamist terrorists for crimes against humanity, including those “scholars of terror” who issued fatwa-s calling for murder. Gannouchi was among those cited by name in the appeal.

In Sudan, eight months of relative press freedom was ended by the regime’s desire to “prevent compromising the Taha investigation.” Heavy censorship was re-imposed, especially on Arabic language newspapers like al-Wifaq, al-Sudani and al-Rai al-Shaab. The press interventions actually seem to have more to do with preventing media support for UN Security Council Resolution 1706, calling for the replacement of the African Union mission in Darfur with 20,000 UN peacekeepers and police, a measure resolutely rejected by the Sudanese government.

The war in northern Darfur has intensified since the May signing of the Darfur Peace Agreement by two resistance factions. Al-Qaeda’s announced intention to intervene in Sudan has supported the government’s assertion that a UN intervention would be self-defeating by actually attracting al-Qaeda militants to Sudan. Regime members from the powerful military and security branches as well as their Janjaweed allies have little desire to see UN forces arresting war crimes suspects for trial by the International Criminal Court.

Both al-Akhdar and Taha were convenient targets in a larger Salafi-Jihadi campaign against Islamic reform, applauded and encouraged by Osama bin Laden in his April message. Basing his argument on the work of 14th century scholar Ibn Qayim al-Jawziya (a disciple of Ibn Taymiya), Bin Laden claimed that “the crime committed by a freethinker is the worst of crimes, that the damage caused by his staying alive among the Muslims is of the worst kind of damage, that he is to be killed, and that his repentance is not to be accepted…” Bin Laden added that many of these freethinkers “are writers in newspapers” and should be killed immediately and “without consultation.”

In a May 2004 address in Beirut on Arab modernity, al-Akhdar’s words seemed to foretell Muhammad Taha’s fate: “The Salafi school instills in the younger generations a religious fanaticism which entails a phobia of dissimilarity and a rejection of the other, to the upper end of approving his or her execution…Muslims other than Salafis are treated as (heretics) or deviators; thus enemies. A student therefore becomes ripe for the execution of all sorts of symbolic and bloody violence; he can burn others with fire… (or) behead those who disagree with him.” Muhammad Taha’s murder remains unsolved.

This article was first published in the September 19, 2006 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Focus