Dr. Andrew McGregor

A talk given to the Civil War Roundtable at the Royal Canadian Military Institute, Toronto, March 28, 2018.

The Intention of this talk is to discuss the little known role of American Civil War veterans in the expansion of the 19th century Egyptian Empire into Africa. As those here tonight are primarily interested in the US Civil War rather than 19th century African history, the talk will begin with a summary of how the Americans came to be in Egypt as mercenaries and their part in Egypt’s failed invasion of Abyssinia (modern Ethiopia). It proceeds in Part Two with profiles of some of the most prominent Civil War veterans serving in Egypt.

American military involvement in Egypt, whether official or unofficial, dates back much further than many might expect. In an early American attempt at regime change in the Middle East, the young republic’s consul in Alexandria, William Eaton, led a motley army composed of a handful of US Marines, and hundreds of Greek, Arab and Turkish mercenaries recruited in Egypt to put Thomas Jefferson’s preferred candidate on the throne of the neighboring Karamanli state of Tripoli in 1805. Following a five hundred mile forced march from Alexandria to Tripoli, Eaton’s frequently mutinous army took the Libyan city of Derna in America’s first overseas land battle.

American military involvement in Egypt, whether official or unofficial, dates back much further than many might expect. In an early American attempt at regime change in the Middle East, the young republic’s consul in Alexandria, William Eaton, led a motley army composed of a handful of US Marines, and hundreds of Greek, Arab and Turkish mercenaries recruited in Egypt to put Thomas Jefferson’s preferred candidate on the throne of the neighboring Karamanli state of Tripoli in 1805. Following a five hundred mile forced march from Alexandria to Tripoli, Eaton’s frequently mutinous army took the Libyan city of Derna in America’s first overseas land battle.

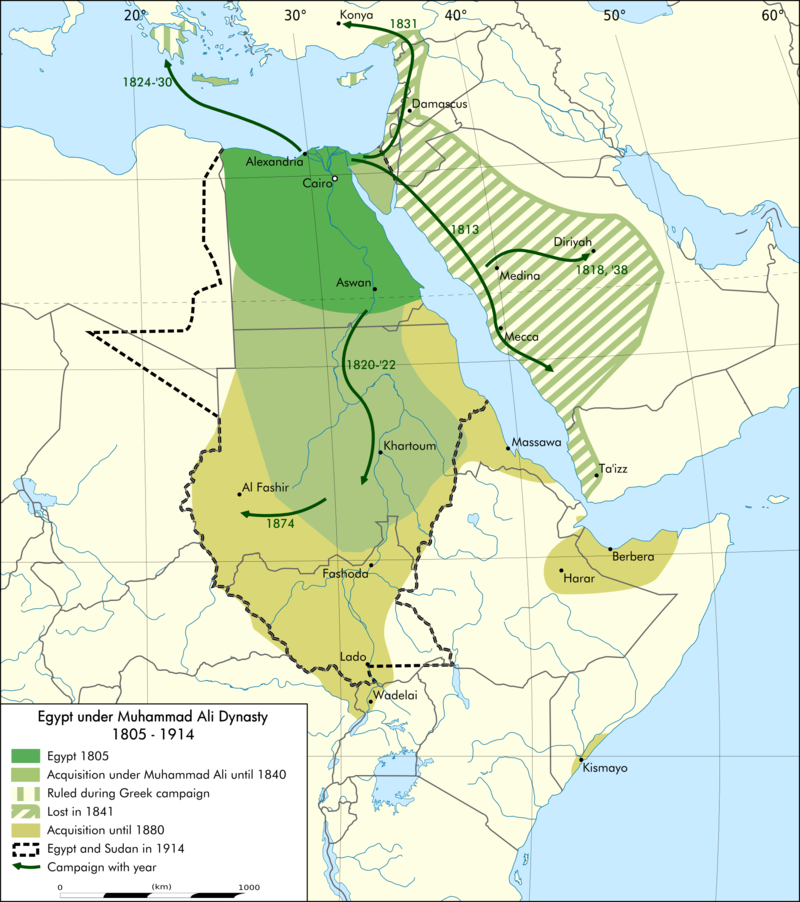

At the same time, an ambitious Albanian, Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha, was emerging as the victor in a power struggle for control of Egypt, still an Ottoman domain. By force and intrigue, Muhammad ‘Ali became the Sultan’s khedive (viceroy) in Egypt, though the Albanian’s real plan was to eventually replace the Ottoman Empire and establish his own hereditary dynasty. In 1811, he slaughtered most of the powerful Mamluk military-slave caste (his last opposition) in an act of treachery. In 1821, the viceroy sent an army south to conquer the Sudan. Three Americans who converted to Islam joined the expedition, though it has never been confirmed whether they were acting as mercenaries or spies.

Egypt and Circassia

Egypt’s ruling class was a combination of Turks and Circassians who typically spoke Turkish and French, but rarely the Arabic of the people they ruled. Circassians from the North Caucasus had been brought to Egypt for centuries as slaves to receive military training and Circassian women, famous for their beauty, filled the harems of the Middle East’s rulers. Though the Mamluk system had been broken in 1811, Circassians and their descendants continued to play major roles in the Egyptian military until the revolt of the Arab officers overthrew the dynasty of Muhammad ‘Ali in 1952.

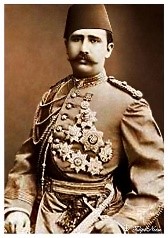

Ismail Pasha and Thaddeus Mott Pasha

Muhammad ‘Ali’s grandson Ismail became the fourth Khedive in the dynasty’s line in 1863. It was a good time to take over; Egypt’s cotton industry had filled the government coffers as Egypt profited from the Civil War blockade around the cotton-producing southern states.

Ismail was determined to consolidate Egyptian power over the entire Nile Basin as well as the Red Sea coast. Though Egypt had a large degree of independence, the Khedive was still the servant of the Ottoman Sultan and Egypt was expected to contribute militarily to Ottoman wars if called upon.

To build his empire Ismail required soldiers from a nation with no strategic or colonial interest in Africa. The sudden availability of many experienced officers after the American Civil War fit the bill perfectly.

Unfortunately, Ismail’s combination of ambition, extravagance and enthusiasm for borrowing cash on the international money markets would ultimately bring about his downfall and an end to the American military presence in Egypt.

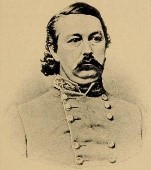

Major General Thaddeus Phelps Mott Pasha

Major General Thaddeus Phelps Mott Pasha

To recruit these officers, Ismail turned to Thaddeus Phelps Mott, an American serving as a major-general in the Ottoman Army.

When the New York City-born Thaddeus Mott enlisted in the Union Army as a 30-year-old in 1861, he was already a veteran of Garibaldi’s Redshirts in Italy and the Mexican Army. He had also spent several years at sea as a mate on clipper ships. Fluent in a number of languages, Mott was an excellent swordsman and dead shot with pistols who enjoyed duelling.

As a Union artillery commander, Mott saw heavy action in the battles of the Seven Days, but some of his most desperate moments came in his native New York as a lieutenant colonel of cavalry during the 1863 Draft Riots. Facing thousands of furious rioters, Mott killed one man with his saber who was trying to pull him from his horse. Mott then ordered the guns under his command to sweep the streets with grape and canister shot.

Three years after the war Mott joined the Ottoman Army’s general staff and was stationed in Egypt. Seeking Western military experts who did not need to clear all the Khedive’s orders with their embassy (as did Ismail’s French advisors), Ismail turned to Mott to recruit American civil war veterans who were free of colonial baggage.

Mott in turn contacted General William Tecumseh Sherman, who agreed to recommend a number of veteran officers from both sides of the Civil War. Sherman had visited Egypt in 1869 and was well treated by the Khedive.

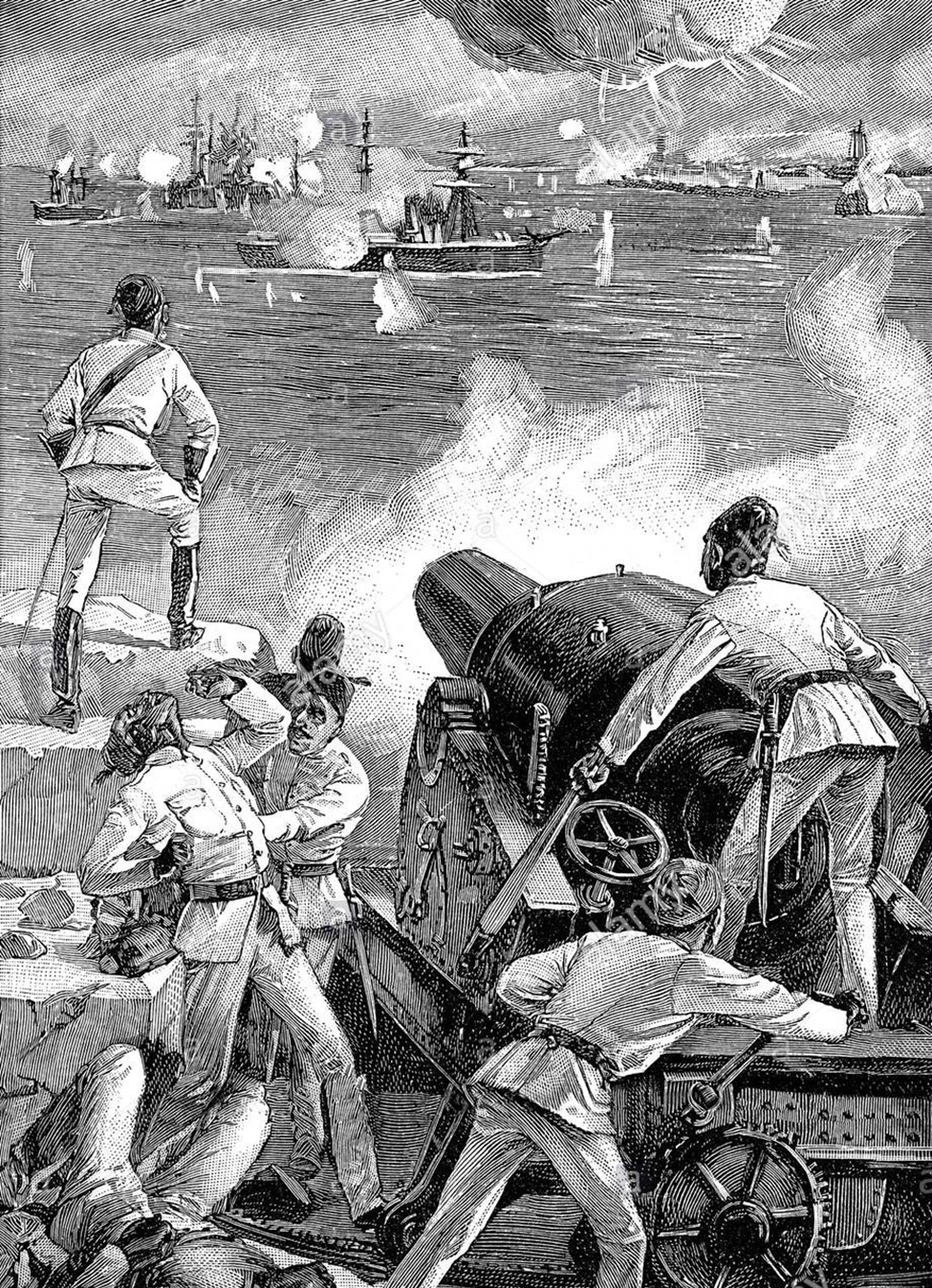

Battle of the Shipka Pass, 1877

Battle of the Shipka Pass, 1877

Mott became aide-de-camp to Ismail Pasha in 1870, but declined to renew his contract in 1874. He instead returned to Turkey to take part in the Ottoman wars in the Balkans, distinguishing himself against the Russians at the Battle of Shipka Pass in 1877. Mott died in Paris in 1894.

Many of Sherman’s recommendations appear to have been made with the goal of sending discontented Union officers on half-pay and Confederates of suspect loyalty out of the country. A number of key Civil War figures, including former Confederate Generals Joseph Johnston, P.G.T. Beauregard and George Pickett, considered the proposal but declined for various reasons. However, service in Egypt was considered respectable employment and many of the officers who accepted came from some of the most distinguished families in America.

The Americans Arrive

On their arrival in Egypt, the Americans found an army suffering from illiteracy, no command structure, no intelligence apparatus, no signals corps, antique artillery and persistent ammunition shortages. The entire Egyptian army possessed only three maps.

The Citadel in Cairo: Headquarters of the Egyptian Army and Home of the American Staff

The Citadel in Cairo: Headquarters of the Egyptian Army and Home of the American Staff

Some of the Americans were put to good use in exploration, training and engineering projects, while others had little to do and killed the boredom with drinking and dueling over petty disputes, some of them dating back to the Civil War. Many of these latter officers made early returns to the United States.

There was no pay department in the Egyptian Army, which at times forced the Americans to collect their salaries at gunpoint when it was months in arrears. Otherwise they accumulated debt which they had little hope of repaying, making the avoidance of creditors their main occupation.

As Muslims, the ladies of the Egyptian aristocracy were strictly off limits to the Christian Americans. There were Syrian, Greek and Armenian Christian women in Egypt, but they tended to live the same veiled and secluded life as their Muslim counterparts. The Americans instead turned for female companionship to the European ladies performing at the Cairo theaters and opera. While some French officers of Napoleon’s occupation army (1798-1801) had converted to Islam to marry Muslim women, it does not appear that any of the Americans did the same.

On a professional level, there were difficulties from the start in relations with the existing officers of the Egyptian Army, who resented the American presence and no doubt endured a certain amount of arrogance from the Civil War veterans. Egypt was a culture shock for many Americans; one officer described his surprise that eunuchs in the royal court were “beings of great importance” and was warned that they were not to be offended on any account as they had the ability to inflict serious harm on anyone who did so, including Americans.

The Invasion of Abyssinia

Ismail’s expansion into the Horn of Africa brought his troops into conflict with those of the Abyssinian emperor, Yohannes IV. After an Egyptian detachment was massacred, it was decided to send a massive invasion force under Ismail’s son, Prince Hassan Pasha, to punish the Abyssinians.

Emperor Yohannes had actually sent a letter to the US Secretary of State in 1872 requesting US help in preventing Egyptian moves on Christian Abyssinia. He also proposed a bilateral commercial treaty. No response was sent from Washington, and when Americans did arrive, they were part of the Egyptian invasion force.

Language was a problem throughout the campaign. The command language of the army was Turkish, spoken by officers who refused to learn Arabic, deriding it as the language of Egypt’s fellahin peasantry. Translators were thus needed to communicate with the Arabic-speaking rank and file. Some French-speaking Americans could communicate with the Turko-Circassian officer corps, but the rest required translators to speak to both officers and men, making the transmission of orders slow and complicated.

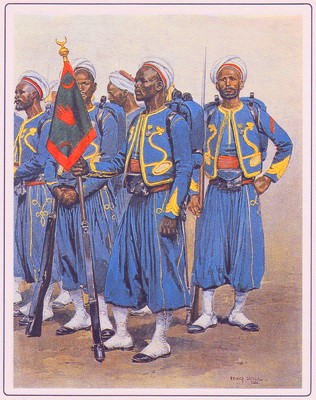

The Americans were also in the strange position of fighting their fellow Christians on behalf of a Muslim nation, but they tended to regard Abyssinian Orthodoxy as a barbaric form of the Christian faith. The Americans were also astonished that the Egyptians insisted on including a regiment of Sudanese blacks in the expeditionary force. Their own prejudices made them overlook the fact that the Sudanese troops were the finest and most experienced in the Egyptian Army. Many in the regiment had distinguished themselves fighting on behalf of Maximillian in Mexico at the same time the Civil War was raging north of the border.

Once in Abyssinia, both Americans and Egyptians alike were shocked by the extreme form of psychological warfare used by the Abyssinians. Prisoners were subjected to horrible genital mutilations and then released naked and bleeding to find their way back to Egyptian lines. The impact on the Egyptian troops was devastating.

During a massive battle at Gura that lasted two days in March 1876, the Egyptian Army was badly defeated by native troops armed with far inferior weapons. American officers complained that the Egyptians failed to attack, preferring instead to “stand still and be killed like sheep.” The Americans attributed this fatalism to the work of the Islamic Imams attached to the expedition and the failure of the Turko-Circassian officers to adopt an aggressive attitude.

While the rest of the Egyptian officer corps returned home to acclaim and decorations, the Americans were ordered to remain at the Red Sea port of Massawa through the brutal summer heat. When they were finally allowed to return to Cairo, they found the Turko-Circassian officers had prepared the way with humiliating accusations of American incompetence.

In 1877, Prince Hassan led an Egyptian expeditionary force to assist the Ottoman Turks in their war against Russia. The remaining American officers, still blamed for the defeat in Abyssinia, were not welcome.

By 1878, most of the American mercenaries had been decommissioned and sent back to the United States. Because of a spiraling national debt fueled by Ismail’s financial extravagance and growing political pressure from his main creditors, the British and French, Ismail was forced to abdicate his throne in 1879 in favor of his son, Tawfiq. Ismail died in debauched exile in Constantinople, the final straw being an attempt to guzzle two bottles of champagne in one go.

It did not take long for the achievements of the Americans in Africa to be forgotten. Their service as Christian mercenaries in a Muslim state was eventually regarded as something of an embarrassment in both Egypt and their home country.

End of Part One.

See Part Two at: https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4270