Andrew McGregor

A talk given to the Civil War Roundtable at the Royal Canadian Military Institute, Toronto, March 28, 2018.

See Part One at: https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4253

Part Two – Biographies of the Civil War Veterans in Egypt

Charles Pomeroy Stone fought in most of the major battles in the Mexican-American War and was twice promoted during the campaign for outstanding performance on the battlefield.

When the Civil War broke out, General Winfield Scott put Stone in charge of Washington’s defenses, to which Stone applied himself with great energy. However, a few months later Stone ran afoul of abolitionist Republicans when he followed the government’s own policy by returning runaway slaves to Maryland. Shortly after that, Stone ordered a reconnaissance in force across the Potomac at Ball’s Bluff. Waiting Confederates killed over a thousand Union troops, including their commander, a Republican senator. Stone, a Democrat, was the scapegoat for this disaster. He was denied a court-martial and was instead sent to prison without charges at Fort Lafayette in New York harbor for 200 days. He was released through the intervention of General Ulysses S. Grant, but remained under suspicion as a potential traitor for the rest of the war.

Stone’s military talents were better recognized in Egypt than in his homeland, and he served for eight years as army chief-of-staff and aide-de-camp to Ismail Pasha. He organized a much-needed general staff and created schools for Egyptian soldiers and their children at a time when the army was plagued by illiteracy and thus unable to modernize. A number of the American officers were aware of Stone’s reputation and formed a cabal against him, but Stone handled them perfectly and soon, as one officer put it, had them “eating out of his hand.”

Stone Pasha remained loyal to the dynasty even after nearly all the other Americans had gone home and most notably protected Ismail’s successor Tawfiq during the British bombardment of Alexandria in 1882.

After Stone returned to the United States he continued working as a civil engineer. In 1884 he was the chief engineer on the Statue of Liberty project but fell ill after attending the dedication on a cold blustery day. He died several months later and was buried at West Point.

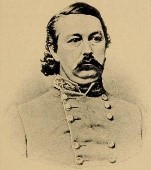

William W. Loring never attended a military school. Instead, he learned soldiering in the field, beginning as a 14-year-old volunteer with the Florida state militia.

Eventually he was commissioned in the pre-Civil War US Army, in which he participated in the 1857-58 Utah expedition (also known as the Mormon Rebellion) and the Indian Wars in the west. Loring lost his arm during the storming of Chapultepec Castle in Mexico. Legend has it that he smoked a cigar during the amputation.

Loring’s Civil War service was infused with controversy; after feuding with his superior Stonewall Jackson, the Confederate general had Loring charged with “neglect of duty” and “conduct subversive of good order and military discipline.” Fortunately for Loring, the War Department did not pursue the charges and wisely sent Loring far away from Jackson. At the Siege of Vicksburg, Loring repulsed an advance by General Grant but his command later became separated from the Confederate garrison inside the city. The Vicksburg commander, John C. Pemberton, blamed Loring for the fall of the city.

Loring would serve ten years in Egypt, beginning as Inspector General of the Army. At one point he escorted his old Vicksburg rival President Ulysses S Grant during his visit to Egypt.

In 1875 Ismail placed Loring in charge of the expedition to punish Abyssinia for its interference in Egypt’s expansion along the coasts of the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean. Ismail implored Loring and Ratib, the Circasssian commander of the Egyptian Army, to work hand in hand. Once in the field, however, Ratib and his fellow Turko-Circassian officers created a parallel command structure using verbal commands, a custom in the Egyptian army where even many officers were illiterate. Furious disagreements between Loring and Ratib over the conduct and purposes of the war were a major factor in the disaster at Gura. Using an Eastern conception of war as a demonstration of strength that preceded negotiations, Ratib insisted on building forts in the Gura Valley. Loring, a fresh graduate of the “total war” philosophy that had destroyed the Confederacy, wanted to continue marching into the Abyssinian interior to destroy armed resistance.

After his return to the United States, Loring wrote his memoir, A Confederate Soldier in Egypt. Loring was buried in St. Augustine, Florida, in 1897 in one of the largest public events in the city’s history. By 2018, local social justice warriors wanted to tear down his grave monument and expel his remains from Loring Park. A statue of Loring commissioned in 1911 still stands at Vicksburg and does not yet appear to be threatened.

Loring’s antagonist, Ratib Pasha, was one of the last Circassians to be brought to Egypt as a military slave in the 19th century. Unlike the earlier Mamluks, who tended to be powerful men with expertise in all the arms of the day, Ratib was only five foot four and roughly one hundred pounds. He had little military training and had served as a royal equerry during the reign of Khedive Abbas Pasha. At some point Ratib angered the Khedive, who struck him. The mortified Ratib attempted to shoot himself but only succeeded in blowing off part of his nose. To make amends, Abbas appointed the small man commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Army.

Unsurprisingly, many of the American professional soldiers had little respect for Ratib and presented him with a series of small humiliations, none of which Ratib was likely to forget. One of the Americans described Ratib as being “as shriveled with lechery as the mummy is with age.” Another officer cited Ratib’s “insane jealousy and intolerance of foreigners,” which compelled him to ignore all military advice from American sources.

The nominal command of the Abyssinian expedition was entrusted to the Khedive’s son, Prince Hassan Pasha. Unfortunately, much of the expedition’s Egyptian command viewed their primary role as protecting the Prince from all harm rather than pursuing the expedition’s political and military goals.

A descendant of French Huguenots who fled to America in 1685, Charles Chaillé-Long joined the pro-Union Maryland Infantry in 1862, achieving the rank of Captain and seeing action at Gettysburg and Harper’s Ferry.

Chaillé-Long was commissioned as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Egyptian Army. His fluency in French was a major asset, as French was commonly spoken by the royal and military elites in Egypt, while English speakers continually required interpreters. He was one of the few American officers to learn Arabic.

Chaillé-Long served on Colonel Charles George Gordon’s staff in Equatoria Province, the southern-most region of the Sudan. His public criticism of Gordon, who had been seconded to Egyptian service, would eventually damage his reputation after Gordon achieved a type of Victorian sainthood following his death at the hands of Egyptian Mahdists in Khartoum (1885).

In 1874, Chaillé-Long led a small party south on a secret mission to expand Ismail’s empire into tropical Africa. He succeeded in securing a treaty with the most powerful king in northern Uganda that made the latter a vassal of Egypt. On the return trip, Chaillé-Long was wounded in a two-hour battle with a rival king. When he reached Gordon’s headquarters in Equatoria he was a fearful sight; one eye closed and blackened, a gunshot wound to his nose, bearded, filthy and half-starved. It took some time for Chaillé-Long to convince Gordon it was really him. For his efforts he was eventually decorated and made a full colonel with the Turkish title of “Bey” (an honorific one step below “Pasha”).

Further expeditions followed to the northeast Congo and Somalia. These took a serious toll on his health, leading to Chaillé-Long’s resignation in 1877.

Chaillé-Long studied law after his US homecoming. He returned to Egypt in 1882 to practice law in the international courts in Alexandria. After US diplomats abandoned the Alexandria Consulate during the British bombardment later that year, Chaillé-Long took over as a temporary, unpaid consul and saved hundreds of Europeans from angry mobs of Egyptians who were massacring Europeans in the streets. He led 160 US sailors and marines as part of an effort to restore order in the city.

In 1887, Chaillé-Long was appointed US consul general in Korea. In his later years he became bitter over what he saw as disproportionate attention given to British explorers in Africa over his own efforts. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery in 1917.

Alexander Macomb Mason Bey began his career in the US Navy before joining the Virginia Navy when the Civil War broke out in 1861. He was captured and sent to the Johnson’s Island prison camp in Ohio for the duration of the war. His relative James Murray Mason was one of the principals in the infamous Trent Affair that nearly brought the Union and Great Britain to blows.

After his release, Mason saw action as a mercenary with the Chilean Navy against Spain in the Chincha Islands War. He joined the Egyptian army in 1870, where he worked as a military trainer and surveyor. He also explored western Uganda on behalf of the Khedive, being the first Westerner to visit the Semliki River, a tributary of the Nile.

Unlike most of the Americans who left after the Abyssinian debacle, Mason stayed on in Egypt, becoming the governor of Massawa on the Red Sea coast and Egypt’s unofficial ambassador to Abyssinia. In 1883 he was the Egyptian representative on a British diplomatic mission to Emperor Yohannes to negotiate a peaceful withdrawal of all Egyptian garrisons on the Red Sea coast, though these bases were quickly taken over by the Italians, who had their own designs on Abyssinia.

He stayed on in Cairo until he died in 1897 during a rare visit to his homeland.

Born in Paris, Raleigh Colston seemed to live life under a black cloud. He did not arrive in his adoptive father’s native Virginia until he was 17. He managed to avoid an uncle’s determination that he should become a Presbyterian minister and enrolled at Virginia Military Institute (VMI). He taught there alongside Stonewall Jackson after graduation and commanded a guard of VMI cadets at the execution of abolitionist John Brown. When the war came, he was quickly made a Brigadier in the Confederate Army despite a lack of combat experience. He was strongly criticized for his performance at the Battle of Seven Pines, which was followed by a six-month illness. Nonetheless, with Jackson’s sponsorship, he was made a divisional commander until his performance at the Battle of Chancellorsville led to being relieved of his command by General Robert E. Lee, commander of the Army of Northern Virginia. Later in the war, Colston served under General PGT Beauregard at the Siege of Petersburg.

After the war, Colston joined the Egyptian Army when his attempts to establish a pair of military schools came to naught and his wife was confined to an insane asylum. In 1873, Ismail sent him on a camel-borne expedition to the ancient city of Baranis on the Red Sea to investigate the possibility of linking the Nile to the Red Sea by railroad.

In 1874, Colston fell seriously ill during an expedition to the western Sudanese territory of Kordofan. Rather than return, he insisted on carrying on. Eventually he had to be carried on a camel litter, expecting death at any moment. He was eventually nursed back to health by the wife of a Sudanese soldier for whom he had once done a favor. Partially paralyzed as a result of his illness, he did not return to Cairo until two years after his departure.

On his return to the US, Colston found limited work as a clerk and translator. Having used his Egyptian pay to support his wife and two children, he eventually found himself a penniless invalid living at the Confederate Soldiers’ Home in Richmond, where he died in 1896.

A graduate of West Point, William McEntyre Dye led a Union brigade at the Battle of Prairie Grove, Arkansas and then participated in the Siege of Vicksburg. He commanded a brigade at the Battle of Brownsville in Texas, close to where Sudanese troops he would later command were fighting south of the border in Mexico. He distinguished himself while leading his regiment in an attack on Fort Morgan during the Battle of Mobile Bay.

After the war, Dye joined the Egyptian Army as a colonel and served as assistant chief-of-staff to General Loring during the Abyssinian campaign. Dye was wounded at the Battle of Gura and returned to the US after being court-martialed for striking an Egyptian officer. He then served 11 years as chief military advisor to King Gojong of Korea. Dye learned Korean and wrote a military handbook in that language.

Born on a Kentucky plantation, Charles W. Field graduated West Point and served in the American West under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston in the 2nd US Cavalry. Joining the Confederate forces as a major in 1861, Field fought in Stonewall Jackson’s Valley Campaign and the Peninsula Campaign. His leg was badly damaged at Second Bull Run and never fully recovered. When he returned to the field as a major-general he suffered two more wounds in the Battle of the Wilderness. He led his division at Cold Harbor and the Siege of Petersburg before surrendering his command at Appomattox Court House.

Field joined the Egyptian Army as a colonel of engineers, and later served as the Inspector General of the Army during its Abyssinian campaign.

Field appears to have been one of the few Americans in the Egyptian Army to experience citizenship issues on his return as a consequence of having served in a foreign army. These were overcome when it was pointed out he had served on a private contract and had never pledged allegiance to a foreign head-of-state.

An expert surveyor, Erasmus Sparrow Purdy worked with General Stone in surveying the Sonora and Baja regions of the American west before the war. He served during the Civil War as an officer in a New York infantry regiment.

After joining the Egyptian army, Ismail sent Purdy on various missions to explore the far reaches of his expanding empire, including Darfur, northern Uganda and the Red Sea coast.

Re-dedication of Purdy Pasha’s Grave Monument in Old Cairo

Re-dedication of Purdy Pasha’s Grave Monument in Old Cairo

Like many of the American officers, Purdy fell into debt and was harassed by his creditors. He died bankrupt in Egypt in 1881. Egypt’s Khedivial Geographical Society raised funds for a tombstone in the Protestant cemetery in Old Cairo. With time and neglect Purdy’s grave fell into disrepair until the year 2000, when some long-term American residents of Cairo raised the funds for a new 10-foot tall memorial. A ceremony was held, attended by a US Marine honor guard and US Major General Robert Wilson, who said “We regard Major Purdy as a pioneer in building American-Egyptian military relations,” a significant nod to the role of the forgotten American mercenaries.

When the Civil War started, 15-year-old James Morris Morgan resigned from Annapolis and served as a midshipman in the Confederate flotilla on the Mississippi.

He then helped work the naval batteries at Drewry’s Bluff in Virginia during the Peninsula campaign in 1862. He returned to sea with the Confederate gunboat Patrick Henry in the James River squadron. Morgan then served on the CSS McRae (a former pirate steamer converted to Confederate warship) until its destruction in the Battle for New Orleans.

Morgan then joined the crew of the commerce raider CSS Georgia, which at one point became involved in a battle with Moroccan tribesmen while anchored off the Moroccan coast. Morgan described it as a “most narrow and fortunate escape for us slaveholders,” as they could expect to be murdered or sold into slavery themselves if captured. During the war Morgan’s two older brothers died while serving as officers under Stonewall Jackson.

Morgan did not participate in any significant campaigns in Egypt and seems to have spent most of his time dueling and chasing actresses. A forbidden flirtation with a Circassian princess nearly cost him his life.

After returning to the US, Morgan was hired by General Stone as an engineer on the Statue of Liberty project. He later became the US Consul for Australasia. He described his life in a highly entertaining account, Recollections of a Rebel Reefer, published in 1917. By the time of his death in 1928 Morgan was the last remaining American veteran of the Egyptian Army.

Henry Hopkins Sibley was a graduate of West Point and was decorated for bravery in the Mexican-American War. When the Civil War began, Sibley was fighting the Navajo in New Mexico. He resigned his commission to join the Confederate forces and organized a brigade of Texans. Sibley’s greatest moment came when he led this brigade west in an attempt to capture the Colorado gold mines and reach the Pacific coast to establish a Confederate port in California.

Following a string of victories, the climactic battle of the campaign was fought in 1862 at the Glorieta Pass in the New Mexico territory. Sibley’s men won a tactical victory by driving the Federal forces back through the pass but lost all their supply train in the process, forcing a withdrawal into Texas. This brought an end to Confederate hopes of extending their territory to the Pacific.

Taking command of the Arizona Brigade in Louisiana, Sibley developed an unfortunate reputation for failing to follow orders and alcohol abuse that led to his court-martial in 1863.

Sibley was recruited by Mott after the war and served as the commander of the Egyptian artillery for three years. Sibley helped supervise the construction of Egypt’s coastal fortifications until problems with alcohol returned and he was dismissed from Egyptian service in 1873. The man who almost seized California for the Confederacy died in poverty and was buried in Fredericksburg Confederate Cemetery.

Though largely forgotten by history, Sibley’s character made a brief appearance in the spaghetti western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, which is set in the midst of Sibley’s New Mexico campaign.

Beverley Kennon Junior’s father, Commodore Beverley Kennon, fought in the War of 1812 and the Second Barbary War.

The Governor Moore was an expropriated commercial paddle-wheeler turned into a warship by the addition of guns, iron rails fitted as a ram and cotton bales to protect its boilers. Kennon took command of this hybrid ship without pay and fought it in the furious April 1862 battle just south of New Orleans. At one point the Governor Moore was too close to the USS Varuna to use its bow gun, so Kennon ordered the gun to fire twice through the Governor Moore’s bow to sink the Union ship. By the end of the battle, most of Kennon’s ship was destroyed and 64 of her crew were dead or dying. The ship was run aground and set on fire, but Kennon was captured and endured three years of brutal captivity in the north.

After joining the Egyptian Army, Kennon devised a brilliant system of coastal defense. Instead of constructing large forts to defend Alexandria, Kennon proposed hiding single gun emplacements along the coast with interlocking fields of fire. The guns would be hidden in the sand hills, raised by a hydraulic system of Kennon’s own invention before taking a shot and disappearing again into the sand bank for reloading. Part of Kennon’s defensive works involved a modern wire-guided torpedo designed by Buffalo New York native John Lay, who began designing torpedoes in the Civil War.

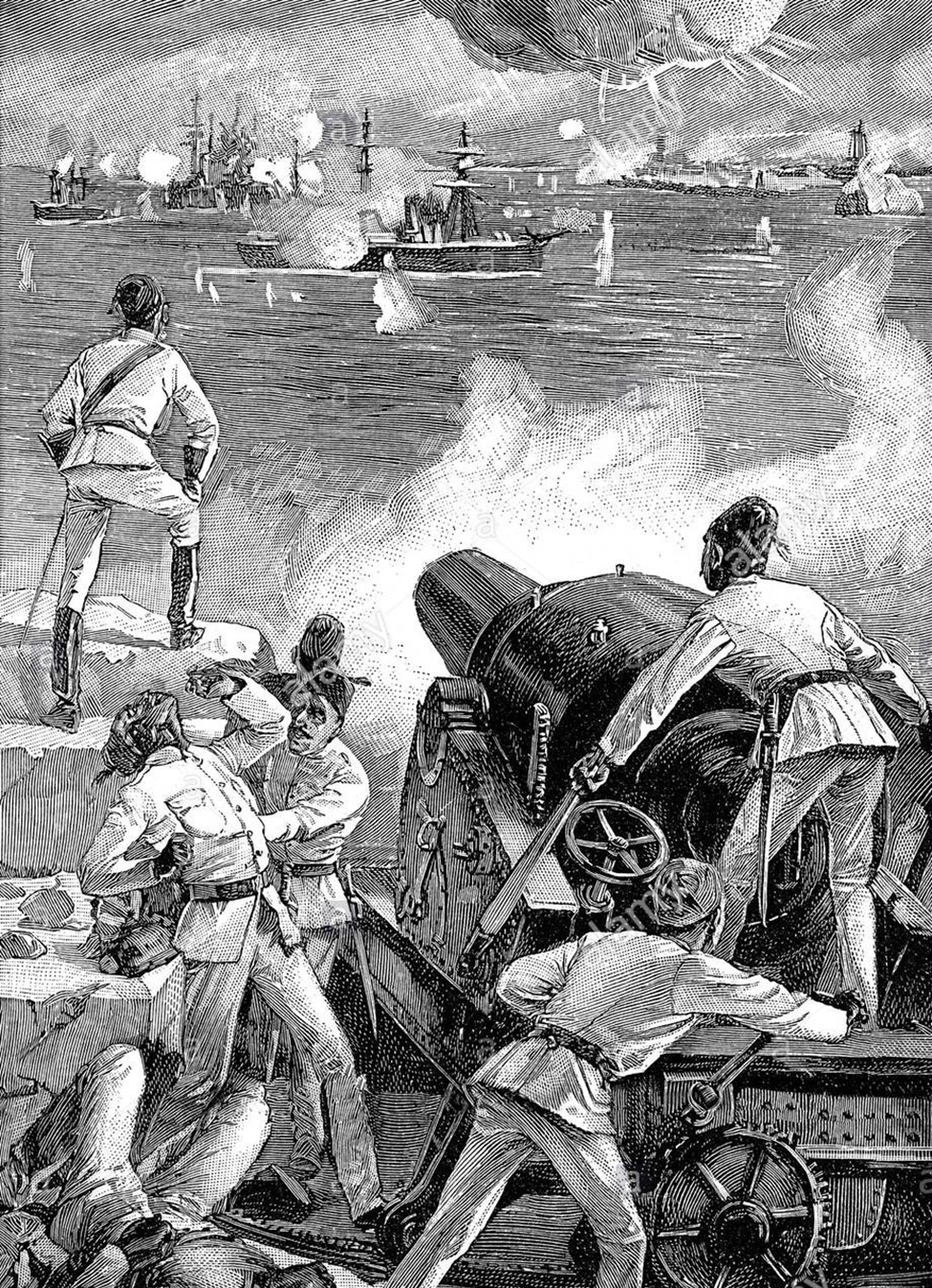

The Bombardment of Alexandria, 1882

The Bombardment of Alexandria, 1882

In 1882 the Arab officers and men of the Egyptian Army led by Colonel Ahmad ‘Urabi revolted against the Turko-Circassian aristocracy. The ensuing chaos put control of the newly-built Suez Canal in jeopardy and European lives at risk from murderous mobs in Alexandria. British and French warships soon arrived off Alexandria, where they began a bombardment of the city.

Despite putting up a good fight, the Egyptian coastal batteries were quickly destroyed by British firepower and British troops were soon investing Egypt. Kennon had finished a working prototype of the defensive system before being told the Khedive’s finances could not afford the completion of the system. Implementation of Kennon’s plan could have easily changed the course of Egyptian history (and that of the Mid-East) by giving Colonel ‘Urabi’s forces the means of fending off the British invaders, who would remain for 76 years.

When the British troops reached the Citadel in Cairo, they destroyed all the maps and charts so painfully prepared by the American officers. The legacy of the American military presence in Egypt was thus eliminated in Egypt while the triumphs and errors of the Civil War veterans in Ismail’s African empire were fated to be forgotten in their US homeland.