Andrew McGregor

AIS Militant Profile

November 20, 2020

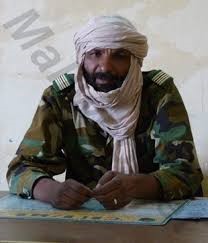

Colonel Bah Ag Moussa Diara (Le Combat, Bamako)

Colonel Bah Ag Moussa Diara (Le Combat, Bamako)

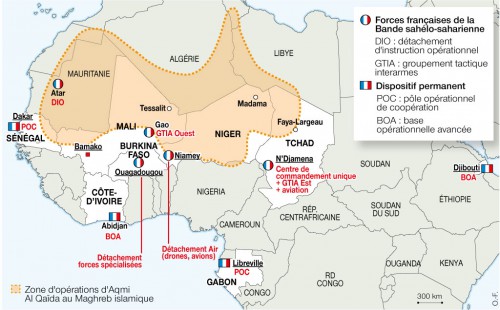

French forces deployed in the Sahel under the “Operation Barkhane” banner scored a notable triumph on November 10, 2020 when they eliminated one of the region’s leading Islamist militants.

The French airstrike in Mali took out Colonel Bah Ag Moussa Diara “Abu Shari’a,” a prominent military leader of the Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM), an al-Qaeda-allied Islamist militant formation active in the African Sahel. Two others were killed in the strike, including Ag Moussa’s aide and his son Hamza. The attack took place as the targets were travelling in a 4×4 seven kilometers from Tadamakat, near Ménaka in the Gao region (one of the three territories of Mali’s arid and sparsely populated north-east, the others being Kidal and Timbuktu). Ag Moussa’s death is of some significance, as his military leadership had helped score a series of successes in the Sahel that demoralized local troops and pushed Mali’s government towards talks with JNIM terrorists led by veteran Islamist Iyad Ag Ghali. The move towards talks with the Islamists was a major factor in the August 2020 military coup in Mali; it should be recalled that it was a 2012 military coup that enabled the launch of an Islamist occupation of northern Mali and the creation of the ongoing Islamist insurgency, which has spread to neighboring Niger and Burkina Faso.

Wreckage of Ag Moussa’s Vehicle (Walid la Berbere)

Wreckage of Ag Moussa’s Vehicle (Walid la Berbere)

Two drones, fighter jets, four helicopters and 15 commandos were involved in the operation, suggesting the French had acquired intelligence aforehand regarding Ag Moussa’s itinerary for November 10. A French military spokesman declined to say whether American intelligence sources were involved in the operation (AP, November 13, 2020). According to French sources, the men ignored warning shots, fighting back with small arms and machine guns before they were hit directly by French fire. The bodies of the three dead were buried on the spot; there was no word regarding the fate of two other occupants of the vehicle (Le Monde, November 13, 2020; Kibaru [Bamako], November 15, 2020),

Ag Moussa was one of the main drivers behind efforts to push the Sahelian jihad into southwestern Mali. A two-time deserter from the Forces Armées Maliennes (FAMA), Ag Moussa’s father was a Bambara from Mali’s populous southwestern region (Diara, or Diarra, is a common Bambara name). Ag Moussa assumed a Tuareg identity through his mother, who came from the aristocratic Ifoghas Tuareg clan in the north-eastern Kidal region (Defense Post/AFP, March 18, 2019; Africa Times, March 24, 2019). Ag Moussa was considered to be very close to JNIM leader Iyad Ag Ghali, with whom he is reported to have received military training in Libya (RFI, March 18, 2019). Most recently, Ag Moussa had a leading role in violent clashes with JNIM’s Islamist rivals in the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara (ISGS). If not the military commander of JNIM (this point is uncertain), he was at least an important and influential military leader with responsibility for training new recruits in weapons and tactics.

Approximately 50-years of age, Ag Moussa was known as a clever strategist and capable tactician whose inside knowledge of the workings and capabilities of the Malian army played a large role in his battlefield successes. The colonel had a special role in training recruits at a camp in the Nara rural commune in the Koulikoro Region of southern Mali. (RFI, March 18, 2019). The base is close to Mali’s northern border with Mauritania and the Wagadou Forest, a traditional zone of jihadist operations.

Ag Moussa deserted the Malian Army to join Tuareg insurgents in the 2007-09 rebellion in northern Mali and Niger. He rejoined the Army through the re-integration protocols of the Algiers Accords that ended the rebellion. As a newly-appointed colonel, he was put to work combatting banditry and recalcitrance in his native Kidal.

With the launch of a new Tuareg rebellion in northern Mali in late 2012, Ag Moussa deserted once again, briefly joining the secular rebel Mouvement national de libération de l’Azawad (Azawad National Liberation Movement) before defecting to their Islamist rivals, Iyad Ag Ghali’s Ansar al-Din (Supporters of Religion). Ag Moussa was accused of being the military commander of Ansar al-Din forces who brutally slaughtered 128 FAMA prisoners at Aguelhoc in January 2012 after the poorly supplied garrison ran out of ammunition (L’indicateur du Renouveau [Bamako], January 26, 2016).

Victims of the Aguelhoc Massacre

Victims of the Aguelhoc Massacre

He also took part in several battles in northern Mali before the French military intervention in the Spring of 2013. Like many Tuareg militants, Ag Moussa then joined the newly-formed Haut Conseil pour l’Unité de l’Azawad (HCUA) as a means of publicly disassociating himself from the extremists being pursued by French and Chadian forces, though he continued working for Iyad Ag Ghali and recruited for Ansar al-Din. According to the UN, his half brother, Sidi Mohammed Ag Oukana, serves as Iyad Ag Ghali’s advisor on religious affairs (UN Security Council, August 14, 2019).

After taking charge of most of JNIM’s military operations in 2017, Ag Moussa increased the tempo of JNIM operations in central Mali, the region at the physical center of Mali’s ethnic and cultural divide. In 2019, the UN reported that Ag Moussa was the new commander of JNIM’s Katibat Gourma (Gourma Brigade) following the death of its Tuareg founder, Almansour Ag Alkassoum.

FAMA insisted that Ag Moussa directed the major attack on a Malian military post at Dioura in the Mopti region of south-central Mali in March 2019. Twenty-six Malian soldiers died in the strike, with 17 men wounded and an additional loss of several armored vehicles. JNIM admitted three dead.

However, JNIM’s media arm, the Zallaqa Foundation, insisted the raid was carried out by the Fulani Katiba Macina, led by Fulani jihadist Amadou Koufa and part of the JNIM coalition since 2017. The JNIM statement said the attack was retribution for the government’s “heinous crimes” against the Fulani. The message also cited the lack of international support for the Fulani and the presence of French military forces in the Sahel as reasons for the attack (Kibaru [Bamako], March 23, 2019). Ag Moussa was known to work very closely with the Katiba Macina, so it is possible that Ag Moussa may have taken part in the operation without actually being its official leader. Since then, Ag Moussa was credited with leading the November 1, 2019 attack on the FAMA base at Inelimane, in which 50 soldiers were killed. The former colonel became a US specially designated terrorist in July 2019, followed by the imposition of UN sanctions as an al-Qaeda associate the next month.

Morale, pay and equipment in FAMA are all poor. Real fighting is carried out by the French, with the Malian military still indulging in politics, struggling to take control over a state they have no means or training to run. The French military presence has become increasingly unpopular, with President of Mali Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta resigning on August 19, 2020 amidst large anti-French street demonstrations in Bamako.

(AFP)

The multinational Task Force Takuba, intended to relieve pressure on the French military which has lost over 50 men in combat operations in the region since 2013, is still in its early stages. Some 50 members of the Estonian Special Forces began operating alongside French troops in October; they are expected to be joined in the coming months by 60 Czechs and 150 Swedes, with the latter also deploying three Blackhawk helicopters. A small Greek deployment is expected soon, though this has been held up by growing tensions with Turkey. Other European states have committed to joining TF Takuba or are exploring the idea, including the UK, Portugal, Belgium, Germany, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Ukraine and Italy, but deployment has been held up by COVID-19 and, in some cases, failure to obtain parliamentary approval (Greek City Times, November 24, 2020; FranceTVInfo, November 9, 2020; AFP, November 5, 2020).

French forces go from victory to victory over the jihadists, but they are only a strike force, no longer a colonial force of occupation. In this sense, they have become an independent arm of the Malian state, operating without reference to the putschists in Bamako. Yet killing jihadists and their leaders cannot end the jihad, which is ultimately a political problem. The political instability generated by the military coup and the promised creation of a new civilian government pushes military and diplomatic progress back to the starting point, though the putschists have at least vowed to honor their alliances with the G5 Sahel, Takuba, MINUSMA and France’s Operation Barkhane (FranceTVInfo.fr, August 19, 2020).

Perhaps most importantly, France has likely succeeded in derailing the continued pursuit of unwanted negotiations between the terrorists and the new regime in Bamako. On the other hand, the French attack is yet another example of the ever-growing reliance of Mali’s military on French forces to conduct successful anti-terrorist operations that enable the nation’s continued survival and avoid a new descent into the political chaos surrounding the Islamist occupation of the north in 2012-13.

The day before the strike on Ag Moussa, Operation Barkhane commander Major General Marc Conruyt noted that JNIM had been taking advantage of a recent French focus on targeting Islamic State personnel and assets, adding that JNIM was still “the most dangerous enemy for Mali and the international forces” (AFP, November 9, 2020). Ag Moussa’s carefully engineered death was a potent reminder to JNIM and its supporters of France’s determination to restore regional stability by ridding the Sahel of religious extremists.