Andrew McGregor

June 26, 2015

Expectations that the election of new Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari would lead to effective military measures against northeast Nigeria’s Boko Haram militants have been dashed in recent weeks as the terrorist group carried out strikes on Chad and Niger, in addition to an intensified campaign of suicide bombings within Nigeria.

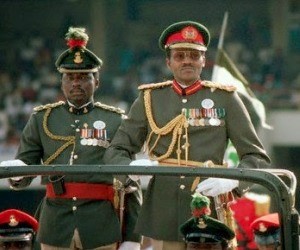

General Muhammadu Buhari in 1983

General Muhammadu Buhari in 1983

Buhari, who once served as the military governor of Borno State, the region most affected by the Boko Haram insurgency, is determined to open the troubled Lake Chad region, the focus of the militants’ recent activities, up to oil exploration, but this requires a stable environment in the region first (Vanguard [Lagos], April 20, 2015). Buhari led a lightning strike against Chad in 1983 on several Lake Chad islands whose sovereignty was disputed by Nigeria, but did so without the authorization of civilian president Shehu Shagari. [1]

In the meantime, the newly elected president used his first trips abroad as president to visit his counterparts in Niger and Chad, a clear sign that Buhari intends to make a break from the relatively uncooperative approach of ex-President Goodluck Jonathan that helped breed distrust and even personal animosity among the region’s leaders. Talks were focused on security issues and the necessity of improving cooperation in this area.

Boko Haram leader Abubakr Shekau meanwhile, in March, pledged his movement’s allegiance to the Islamic State at the same time that Boko Haram was suffering serious reverses on the battlefield due to an infusion of new weapons and foreign military trainers in the lead-up to Nigerian elections. The movement now uses the official name Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP).

Problems of the Nigerian Military Inherited by President Buhari

Most of the fighting in the last two years has been carried out by the Nigerian Army’s 7th Division, specifically created from three armored brigades in August 2013 for use against Boko Haram and headquartered in Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State. The 7th Division replaced the multi-service Joint Task Force (JTF), which had been criticized for its indifference to civilian casualties in the battle against Boko Haram. However, certain problems have remained endemic to the Nigerian military, including:

• Poor air-ground operational coordination; air assets routinely fail to provide battlefield support;

• Demoralization to the point of mutiny in some units, often linked to insufficient training and a failure to pay salaries;

• Failure to keep Nigerian arms, ammunition and armored vehicles out of the hands of militants;

• Poor leadership that blames undertrained and under-equipped troops for their failure;

• Rampant corruption, even leading to battlefield shortages of arms and ammunition despite one of the largest defense budgets in sub-Saharan Africa, and political indifference. Ethnic rivalries also persist in the officer corps;

• Inferior logistics, an inability to maintain or at times operate complex equipment and a slow medical response on the battlefield;

• Indifference to civilian lives or human rights issues, a reliance on civilian vigilante groups and the penetration of the intelligence services by militants;

• Poor intelligence work, based partly on poor relations with local groups;

• A generally compliant media that encourages false confidence in the military;

• Unwillingness to cooperate in the field with regional allies, who are generally regarded by the Nigerian military as junior partners regardless of the reality on the ground.

While Chadian and Nigérien forces made substantial gains against Boko Haram earlier this year, there were still complaints that Nigeria was preventing hot pursuits of retreating militants that would have ultimately resulted in their destruction (Vanguard [Lagos], June 11, 2015). However, with President Jonathan in a tight race for re-election, the Boko Haram fight took on a new urgency, with Jonathan’s administration turning to Eastern European mercenaries to improve air-ground coordination and South African private military contractors to provide training in new weapons and tactics. The latter contractors were part of a company known as Specialized Tasks, Training, Equipment and Protection (STTEP), headed by Colonel Eeben Barlow, a widely-known private military contractor and former commander of the South African Defense Force’s 32 Battalion. STTEP concentrated on creating a mobile Nigerian strike force “with its own organic air support, intelligence, communications, logistics and other relevant combat support elements.” [2]

During their three-month contract, Barlow’s tactical approach, known as “relentless offensive action,” helped reverse recent gains by Boko Haram. Unfortunately, these gains appear to be in remission following the departure of the South Africans in late March.

In an effort to maintain the momentum, Buhari used his May 29 inauguration speech to announce he was shifting the command center for military operations against Boko Haram from Abuja (the Nigerian capital) to Maiduguri, the capital of Borno State and a frequent target for Boko Haram attacks since the election (Vanguard [Lagos], June 5, 2015).

Post-Election Attacks

Following the elections, Boko Haram launched an offensive using terrorist tactics almost immediately after Buhari took power. Since then, the group has also responded to increasing military pressure by shifting away from trying to occupy a “caliphate” in the Borno/Yobe/Adamawa States region of northeast Nigeria to the renewed use of terrorist methods, such as slaying inhabitants of defenseless villages in raids and hitting urban centers with suicide bombers targeting concentrations of people at markets, checkpoints and weddings. As well as mass raids on Maiduguri, Boko Haram has expanded its suicide bombings to the previously untouched city of Yola, the capital of Adamawa State (Vanguard [Lagos], June 5, 2015; Daily Trust [Lagos], June 6, 2015).

A Regional Solution: Reviving the Multi-National Joint Task Force

Though the Nigerian security forces found themselves hard-pressed after Buhari’s election, on a larger scale, there were signs that Boko Haram’s regional opponents were now ready to work out a common strategy through the revitalization of the Multi-National Joint Task Force (MNJTF), an anti-terrorist alliance of Nigeria, Chad, Niger and Cameroon, with a non-military representation from Benin. The move promised to reverse the isolated efforts of alliance members during the Jonathan regime, with Chadian President Idriss Déby Itno complaining that, two months into the war, Chad’s military still had insufficient contact with the Nigerian military: “The Nigerian Army and the Chadian Army are working separately in the field. They are not undertaking joint operations. If they were [carrying out] joint operations probably they would have achieved more results” (Punch, [Lagos], June 9, 2015).

Nigerian Troops with Captured Boko Haram Banner

Nigerian Troops with Captured Boko Haram Banner

Participating nations will begin deploying troops to the MNJTF on July 30, 2015. The force has a planned strength of 8,700 personnel while its operational zone will be split into three sectors. Each contributing nation will be responsible for equipping and maintaining their own units (Vanguard [Lagos], June 11, 2015). The post of MNJTF commander will be filled by a Nigerian until the end of the conflict with Boko Haram (a point Buhari insisted upon), while a Cameroonian will hold the post of deputy force commander and a Chadian will be the chief-of-staff. The latter two positions will rotate every 12 months. The task force’s headquarters will be located in N’Djamena, the Chadian capital and headquarters for France’s African security operations known as Operation Barkhane (Punch [Lagos], June 11, 2015).

The first MNJTF commander is Major General Tukur Yusuf Buratai, whose most notable former posting was as the commander of Joint Task Force, Operation Pulo Shield, which targeted oil thieves and pirates in the Niger Delta region (Daily Post [Lagos], June 3, 2015). General Buratai may have a personal interest in destroying Boko Haram; while he was away commanding Joint Task Force operations in the southern Niger Delta in 2014, his large Borno State home was attacked and burned by Boko Haram militants, who also killed one guard (Premium Times [Abuja], February 20, 2015). Under President Jonathan, Nigeria pledged to cover the main cost of funding the MNJTF, a pledge President Buhari renewed in June with an offer of $100 million (Vanguard [Lagos], June 11, 2015; This Day [Lagos], June 11, 2015).

Nigeria’s Demoralized Army

Poor morale has inhibited a strong Nigerian military response to Boko Haram. In late May, some 200 Nigerian soldiers were dismissed from service for cowardice, with many likely relating to the fall of the town of Mubi (Adamawa State) to Boko Haram in late October 2014. Troops in Mubi bolted for the state capital of Yola when Boko Haram attacked, and Nigerian authorities claimed to have “video evidence of their cowardice” (This Day [Lagos], May 28; Premium Times [Abuja], October 29, 2014). One of the dismissed soldiers claimed that they had only followed orders from their officers to withdraw from Mubi due to inadequate weapons (This Day [Lagos], May 28, 2015). Another sacked soldier claimed troops were given only five bullets each as well as expired bombs made in 1964. The troops’ heaviest weapons only had a range of 400 meters while they were facing militants using anti-aircraft weapons with a range of over 1,000 meters (Vanguard [Lagos], May 28, 2015 This Day [Lagos], May 28, 2015).

As of May 21, Nigerian military authorities were able to confirm that no less than 579 officers and soldiers were facing courts martial in Abuja and Lagos for offenses including indiscipline, refusal to obey orders, insubordination and cowardice (This Day [Lagos], May 21, 2015). Sixty-six other soldiers have already been condemned to death for mutiny and their failure to confront Boko Haram, though these sentences might be revisited by the new president.

New Equipment to Turn the Tide

Nigerian Ambassador to the United States Adebowale Adefuye expressed his government’s displeasure with what they perceived as the United States’ unwillingness to support the struggle against Boko Haram or provide lethal military equipment based on “rumors, hearsays and exaggerated accounts” of human rights abuses by Nigerian forces in Borno (Punch [Lagos], November 13, 2014). After Nigeria’s attempt last year to purchase U.S.-made Bell AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters from Israel (which had replaced their Cobra fleet with newer AH-64 Apache helicopters) was blocked by the United States, which retains control over resale of such equipment, Nigeria turned to other suppliers for its needs:

• Nigeria began to deploy newly acquired French-made Aérospatiale Gazelle attack helicopters in February, though it was unclear how many were purchased or from whom (DefenceWeb, March 16, 2015). What was clear, however, was that the helicopters were flown at first by foreign military contractors in support of operations carried out by Nigeria’s 72 Strike Force in Borno State;

• Two Eurocopter AS-332 Super Puma helicopters in storage since 1997 are being refurbished and upgraded by Eurocopter Romania. One of two existing Nigerian Super Puma helicopters was lost in a crash in Lagos on April 11 (This Day [Lagos], April 11, 2015);

• Nigeria’s air force will reportedly soon deploy Russian-made attack helicopters ordered in August 2014 (DefenceWeb, March 16, 2015). The new acquisitions include six Mi-35 (NATO reporting name “Hind-E”), an updated export version of the well-known Mi-24 (NATO reporting name “Hind”) designed for harsh climates. Besides its attack capabilities, the Mi-35 can also act as a transport, carrying eight fully equipped soldiers. Nigeria is also obtaining twelve Mi-17Sh (NATO reporting name “Hip”) helicopters, an export version of the multi-purpose transport/gunship Mi-17;

• Nigeria appears to be using five Chinese-made CASC CH-3 Rainbow UAV’s in combat missions against Boko Haram. A photo of one such craft downed in Borno State in January shows the drone is equipped with a variety of missiles, most likely YC-200 guided bombs and AR-1 air-to-ground missiles; [3]

• The United States has also permitted the sale of two Dassault/Dornier Alpha light attack/trainer jets to help replace losses (DefenceWeb, March 30; May 26).

Training on the new equipment, especially helicopter gunships and armored vehicles, was provided in part by South African private military contractors (BBC, March 13). Both air and land forces are being upgraded with night vision equipment.

Nigeria has also embarked on a major arms acquisition program that includes procuring 16 T-72 tanks and rocket launchers from the Czech Republic and armored personnel carriers from Ukraine, China, South Africa and Canada to provide greater battlefield mobility, firepower and security. Buhari’s election has also allowed the United States to reappraise its relations with Nigeria, deeply strained by the corruption and human rights abuses of the Jonathan regime (Reuters, June 5, 2015).

Regional Dimensions of the Conflict

Boko Haram is now targeting Chadian and Nigérien communities in response to the participation of these nations in the anti-Boko Haram military coalition. On June 18, militants crossed the border from Borno into the Diffa region of Niger, where they slaughtered at least 38 people, mostly women and children (AFP, June 19, 2015). Only days earlier, motorcycle-riding suicide bombers struck a police training college and the central police station in the Chadian capital of N’Djamena on June 15, killing 27 people. Boko Haram’s message was clear: despite Chad’s military offensive against the group, the group remained capable of striking the city, which serves as headquarters for the revamped MNJTF and France’s counter-terrorism Operation Barkhane (Reuters, June 15, 2015).

Vowing that “spilling the blood of Chadians will not go unpunished,” Chad’s air force claimed to have carried out airstrikes on six Boko Haram bases in Nigeria in retribution (Reuters, June 18, 2015). However, these claims were quickly rejected by Nigeria’s military, which insisted the air strikes must have been carried out in Niger. The inability of Nigeria and Chad to even agree on where air strikes were carried out demonstrates that cooperation is still in short supply. The somewhat testy statement issued by Nigerian Director of Defense Information Major General Chris Olukolade spoke to continued resentment of the military coalition among Nigeria’s military leadership: “Although the terms of the multilateral and bilateral understanding with partners in the war against terror allow some degree of hot pursuit against the terrorists, the territory of Nigeria has not been violated as insinuated in the reports circulated in some foreign media” (Premium Times [Abuja], June 18, 2015). Other measures announced by Chadian authorities included a round-up of foreigners and bans on the burqa and niqab (Nigerian Guardian [Lagos], June 20, 2015).

In addition, recognizing that underlying the Boko Haram rebellion is the extreme poverty of northeast Nigeria and neighboring regions around Lake Chad, the Lake Chad Basin Commission (consisting of Nigeria, Chad and Cameroon) is implementing an emergency $65 million development initiative in the region to “combat the causes and conditions that favor the development of insecurity” (Vanguard [Lagos], June 11, 2015).

Conclusion

Part of the reason the Nigerian military has had difficulty in establishing firepower superiority against the insurgents is that most of Boko Haram’s military equipment has been seized from Nigerian Army stocks, leaving both sides similarly equipped in terms of weapons. The Nigerian military must thus use the other advantages available to state actors, such as effective use of airpower, organized supply systems, troop rotation and employment of foreign technical experts where necessary.

Nigeria’s counter-insurgency efforts seem to have improved, notably through greater use of small numbers of better-trained Special Forces personnel rather than the deployment of large numbers of poorly-trained and poorly-equipped regular army personnel on the frontline. However, the inability of Nigeria’s security forces to prevent or even stem the growth of urban terrorism in the northeast speaks to the continued failure of Nigerian intelligence services to gather actionable intelligence in the region.

At the moment, Nigerian Special Forces personnel and Air Force assets appear to be leading the effort to clear Boko Haram from their bases in the Sambisa Forest. Losses are reportedly heavy (precise figures are hard to come by), and there are still problems in the supply chain, with troops in the field going for days with little water or food (Daily Trust [Lagos], June 6). However, new weapons and tactics will inevitably prove to be only part of a more comprehensive military and economic solution to Nigeria’s expanding Boko Haram insurgency. President Buhari’s new administration can either exploit the renewed goodwill it has encountered from the United States and an eagerness amongst its regional military partners for greater military and economic cooperation, or it can fall back into the familiar patterns of negligence and corruption that have so hampered the struggle against Boko Haram. In this sense, the crisis in the Lake Chad region has reached a crossroads for the Nigerian government.

This article first appeared in the June 26, 2015 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.

Notes

1. See Jack Murphy, “Eeben Barlow Speaks Out (Pt. 2): Development of a Nigerian Strike Force,” April 6, 2015, http://sofrep.com/40623/eeben-barlow-speaks-pt-2-development-nigerian-strike-force/.

2. See Adeoye A. Akinsanya and John A. Ayoade, An Introduction to Political Science in Nigeria, Rowman & Littlefield, 2013, p. 272; Adekeye Adebajo, Liberia’s Civil War: Nigeria, ECOMOG, and Regional Security in West Africa, Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2002

3. See http://www.airforceworld.com/blog/ch3-uav-drone-crashed-in-nigeria/.