AIS Special Report on Ukraine No.3

March 24, 2022

Andrew McGregor

Blue and yellow flags carried by anti-government protesters are a new and unusual sight in the streets of Khartoum. However, these banners are less a show of support for besieged Ukrainians than a rejection of a Sudanese military regime that continues to grow closer to Russia even as President Vladimir Putin’s army carries out widely condemned atrocities and war crimes in a sovereign state. At stake is not only Sudan’s own sovereignty, but the ability of its rulers to offer food security and a path to development.

With the overthrow of President Omar al-Bashir in 2019, Sudan ended over a quarter-century of military-Islamist rule. Though promises were made that a joint civilian-military transitional government would lead to a new era of democratic civilian rule, a military coup in October 2021 ended that experiment and led to the severing of most economic and financial ties to the West, including $US 700 million of American aid.

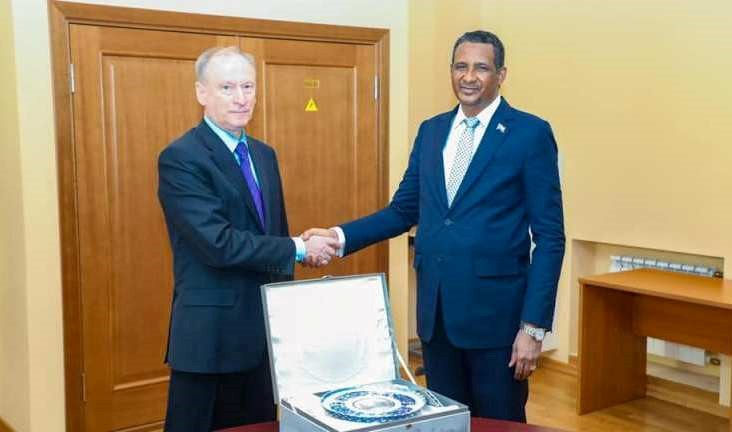

General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan (Mahmoud Hjaj/Anadolu Agency)

General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan (Mahmoud Hjaj/Anadolu Agency)

The junta’s leader, General ‘Abd al-Fattah al-Burhan, is typical of the Islamist military officers who enjoyed great power during al-Bashir’s rule, but his ambitious deputy, Lieutenant-General Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti,” represents a new and growing power in Sudan as commander of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). Created from the remnants of the infamous Janjaweed, the RSF was intended to serve as a paramilitary focused on establishing security in Darfur under the guidance of the National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS – now rebranded as the General Intelligence Services – GIS) rather than the military. The RSF quickly developed a reputation for atrocities and war crimes in restive Darfur. [1] Since then, it has exploited its independence to grow vastly in strength while establishing its own economic base. Besides serving as revenue-producing rental troops in Libya and Yemen, the RSF now acts as a regime-defending internal security force in most Sudanese cities, including the capital of Khartoum, where the RSF was accused of rapes, murders and massacres after al-Bashir’s overthrow.

With Western nations and international institutions avoiding any interaction with Sudan’s military rulers, Russia has helped provide diplomatic support for the coup leaders at the UN and elsewhere. Russia has also provided direct and indirect support to the Sudanese military and the RSF in return for access to Sudanese resources, especially gold, and an agreement to permit the establishment of a Russian naval base on Sudan’s Red Sea coast. Internally, however, Khartoum’s dalliance with Putin’s Russia and the activities of Russian “Wagner Group” mercenaries closely tied to the Kremlin have aggravated opposition to the regime rather than appease it. There have been continuous street protests since the coup, with scores killed by security forces. The participation of Russian mercenaries in repressing popular opposition and manipulating information sources has scandalized many Sudanese. [2]

Rather than back off from an unpopular association with Moscow, Hemetti chose to lead an ill-timed and ill-advised eight-day mission to Moscow only one day before the invasion of Ukraine. Hemetti’s request for supplies of Russian arms and military assistance in exchange for a Red Sea naval base at the same time Russian troops were slaughtering Ukrainian civilians and Sudanese citizens were going hungry was met with disbelief in many quarters.

Sudan, like many other African nations, is a major consumer of Russian and Ukrainian wheat, these sources providing 35% of Sudan’s supply in 2021 (BNNBloomberg, March 15, 2022). Soaring prices for grain are not helped by the retreat of international donors after the military coup, including those agencies that might be the most helpful in securing affordable and reliable supplies. Despite this, Hemetti’s primary focus remained on obtaining weapons rather than provisions.

Sudan abstained on the UN General Assembly motion to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and demand Russia’s immediate withdrawal. Despite intense diplomatic pressure from the US and the EU to condemn Russia’s invasion, the military-dominated Sovereign Council that currently governs Sudan would go no further than calling for negotiations and a diplomatic solution.

Sudan’s civilian opposition coalition, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), has condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine and rejects Russian interference in Sudanese affairs. The National Umma Party (NUP), one of Sudan’s largest, was specific, objecting that Hemetti’s visit to Moscow did not serve Sudanese interests while declaring the invasion was an “unjust war against a free people to force them to give up their sovereignty” (Radio Dabanga, March 1, 2022). Though Russia’s growing presence and influence in Sudan appears to threaten Sudan’s sovereignty as well, events in Ukraine may reverse this trend and even threaten the African nation’s governing structure.

Sudanese Support for Russia – At a Cost

Hemetti and a large Sudanese delegation arrived in Moscow for a week-long visit on February 23, 2022, the day before the attack on Ukraine was launched. It was not Hemetti’s first trip to Moscow; in 2019 he visited on an arms-shopping mission. Since 2017, Sudan has been a leading purchaser of Russian arms, which now represent 50% of Sudanese purchases. [3]

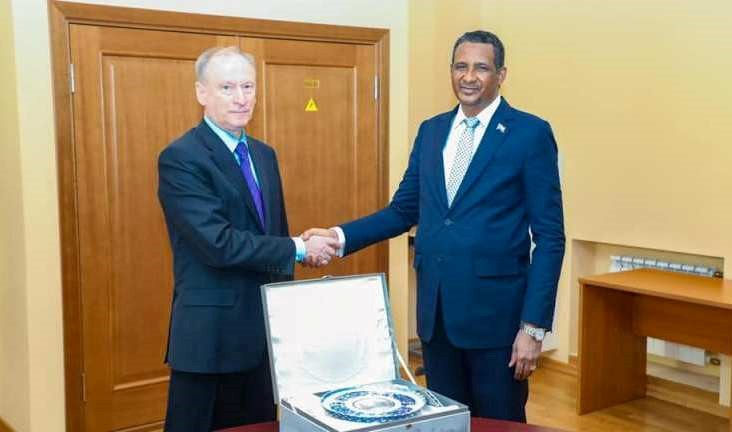

Patrushev and Hemetti, February 25, 2022 (Sudan Tribune)

Patrushev and Hemetti, February 25, 2022 (Sudan Tribune)

Notably, the delegation did not include a representative of the Sudanese armed forces. In Sudan, it is Hemetti’s RSF that works closely with Russian mercenaries of the infamous Wagner Group, who have been deployed in support of the military regime. One of Hemetti’s main concerns was reported to involve obtaining Russian weapons for his RSF as well as the Sudan Armed Forces (SAF) (Sudan Tribune, February 25, 2022). Among the high-end items sought by Hemetti were S-400 anti-aircraft missile systems and Sukhoi Su-35 jet-fighters at a time when tensions with Ethiopia are high. Other countries, such as Egypt and Indonesia, have recently backed out of deals for the purchase of Su-35s due to their second-rate radar systems and the possibility of US sanctions designed to prevent large weapons purchases from Russia (Forbes, January 11, 2022).

Russian-made Sudanese Sukhoi Su-35 in Sudanese Colors (MilitaryWatchMagazine)

Russian-made Sudanese Sukhoi Su-35 in Sudanese Colors (MilitaryWatchMagazine)

On arrival, Hemetti expressed his support for the independence of the two Russian-engineered republics in the Donbas regions and Russia’s military pressure on Ukraine, declaring: “The whole world must realize that [Russia] has the right to defend its people” (Sudan Tribune, February 24, 2022). Hemetti’s remarks seemed to echo Russian assertions that Putin is defending ethnic Russians from genocide at the hands of Ukrainian “Nazis.” Widely condemned almost immediately, Hemetti’s remarks created a diplomatic stir that Sudan’s Foreign Ministry addressed by stating: “We consider that publishing that statement in this manner is a deliberate distortion, taking the speech of the First Deputy out of context, and a cheap attempt to fish in troubled waters” (Sudan Tribune, February 24, 2022). Accused of war crimes himself in Darfur, Hemetti is unlikely to have any qualms about establishing closer ties to Putin’s Russia even as it commits war crimes in Ukraine.

An Arabic-language news-site based in London, al-Araby al-Jadid, claimed that al-Burhan told Egyptian authorities he suspected Hemetti and his RSF of planning a coup to replace him with another military figurehead (Sudan Tribune, February 26, 2022). Though al-Burhan is the senior figure in the junta that overthrew President Omar al-Bashir, Hemetti has emerged as the real power, as witnessed by his direct dealings with senior Russian officials such as Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, Deputy Prime Minister Alexander Novak, head of the Russian Federation Security Council Nikolai Patrushev and Deputy Defense Minister Alexander Fomin.

After Hemetti’s visit to Moscow, al-Burhan made a call to Saudi Arabia to talk to officials there about Red Sea security issues – in other words, a discussion of Hemetti’s views on allowing a Russian Red Sea naval base directly opposite the Saudi cities of Mecca and Jeddah.

Sudanese Gold, Russian Miners

In early March, an executive with a leading Sudanese gold company revealed to the Telegraph that Russia has been smuggling roughly 30 tonnes of gold from Sudan each year to build up its reserves and weaken the effect of sanctions imposed after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Working in collusion with Hemetti and his RSF, Russian mining firm M-Invest (closely tied to the “Wagner Group”), through its local subsidiary Meroe Gold, has been smuggling gold in small planes from military airstrips (The Telegraph, March 3, 2022; Government.ru, November 24, 2017). In response to the allegations, Hemetti said the identity of the end buyers of smuggled Sudanese gold was unimportant; what mattered was who was selling the gold. The RSF chief claimed 40 individuals had already been arrested, but declined to provide any further information (VOA, March 10, 2022). Russian involvement in the Sudanese mining sector began in 2017 with the signing of several agreements between former president Omar al-Bashir and Vladimir Putin.

Sudan’s Minister of Minerals, Muhammad Bashir Abunmo, rejected the claims of Russian smuggling as “baseless accusations” devised to “justify the Western campaign against Russia.” The minister, a member of Minni Minnawi’s faction of the Sudan Liberation Movement (SLM-MM), insisted that Meroe Gold produces only three tons of gold per year, and that much of that was retained by the Sudanese government (Sudan Tribune, March 12, 2022). The Sudanese acting ambassador to Russia, Onor Ahmad Onor, also rejected the claims: “I have nothing to say other than it is fake news and a story created from the imagination of the Telegraph reporter” (VOA, March 10, 2022). Moscow has also denied the allegations.

On Hemetti’s return, the opposition Forces for Freedom and Change, accused Russia of “stealing resources” and interfering in Sudanese affairs to support its role in “regional and international conflicts” (Middle East Monitor, March 3, 2022). Sudan desperately needs the gold to try to avert an economic collapse brought on by the military coup, so any losses due to smuggling will only contribute to the nation’s financial crisis.

Secret documents obtained by anti-corruption NGO Global Witness in 2020 revealed the complex financial network the RSF has established (including its own bank account in Abu Dhabi), allowing it to independently obtain 1,000 vehicles from Dubai suppliers, most of them Toyota 4x4s that can be converted to lightly armored, machine-gun mounted “technicals” of the type widely used in the Sahara and Sahel regions. Important parts of the network appear to be controlled by Hemetti’s younger brothers, Al-Goni Hamdan Daglo and ‘Abd al-Rahim Hamdan Daglo, the deputy head of the RSF. Much of the financing for this network comes from the al-Junaid gold company, which trades in the output of the RSF-controlled gold mines in the Jabal Amr region of Darfur, seized by the RSF in 2017. Al-Junaid is officially owned by ‘Abd al-Rahim Hamdan Daglo and his two sons (Global Witness, April 5, 2020).

RSF operations in Yemen provide another revenue stream, courtesy of financing provided by the United Arab Emirates (UAE). According to Hemetti: “People ask where do we get this money from? We have the salaries of our troops fighting abroad and our gold investments, money from gold and other investments” (Global Witness, December 9, 2019).

A Russian Naval Base on the Red Sea?

After extensive discussions, a 25-year agreement allowing the establishment of a Russian naval base on Sudan’s east coast was signed in 2017 by al-Bashir and Putin, though it was not immediately implemented. [4] The agreement, renewable for further ten-year terms with the consent of both parties, came as al-Bashir complained he needed Russian support to fend off alleged American aggression against Sudan. Under its conditions, Russia will be able to use the base and install 300 Russian personnel to support up to four Russian naval ships (including those powered by nuclear energy) operating in the Red Sea. In return, Sudan would receive Russian arms and other military equipment.

After President Putin authorized his Defense Ministry to establish the Russian base in November 2020, Prime Minister Mikhael Mishustin emphasized that the facility would be “defensive and not aimed against other countries” (Al-Sharq al-Awsat, November 20, 2020). Russia describes the planned base as a “material-technical support facility.”

The agreement was suspended after Sudanese officials had second thoughts about certain clauses in 2021. Many civil and military leaders were less than enthusiastic about the project. Armed Forces chief-of-staff and former Sudanese point-man on the project, General Muhammad ‘Uthman al-Hussein, described the pact as including “clauses that were somewhat harmful to the country,” forcing a general review (AFP, June 2, 2021). Last September, Khartoum was reported to be seeking a modification of the terms surrounding the new Russian base to include not only arms as compensation, but also badly-needed economic assistance. The Sudanese also floated the idea of replacing the 25-year agreement with one covering only five years, with the potential of renewing the agreement up to a 25-year period (The Arab Weekly, September 16, 2021).

The stalled agreement was a focus of Hemetti’s visit to Moscow as the two parties moved towards implementation. On March 3, Hemetti declared: “We have 730 kilometres along the Red Sea. If any country wants to open a base and it is in our interests and doesn’t threaten our national security we have no problem in dealing with anyone, Russian or otherwise” (Reuters, March 3, 2022; AfricaNews, March 2, 2022). Hemetti, however, insisted that the decision was ultimately that of the defense minister, “so it is not my responsibility. But if there is any benefit from the base, in addition to its commitment to community responsibility, for the people of eastern Sudan, we do not object to its establishment” (Sudan Tribune, March 2, 2022).

Hemetti added that he was perplexed by the opposition to a Russian base in Sudan, pointing out that many African countries hosted military bases belonging to foreign powers. Authorities in Cairo were reported to be surprised and angered by Hemetti’s remarks, having no desire to see Russian naval ships patrolling off Egypt’s Red Sea coast near the entrance to the Suez Canal. A demand for clarification was issued almost immediately (Middle East Monitor, March 7, 2022). Egypt abandoned its initial neutral stance on the conflict in Ukraine to vote in favor of the UN General Assembly’s denunciation of the Russian invasion. The change came partly because of diplomatic pressure applied by Ukrainian and American representatives despite demands from the Russian ambassador that Egypt support the invasion.

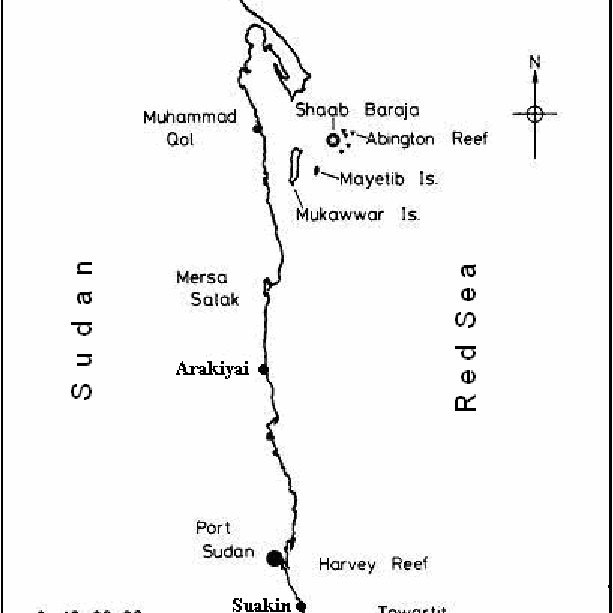

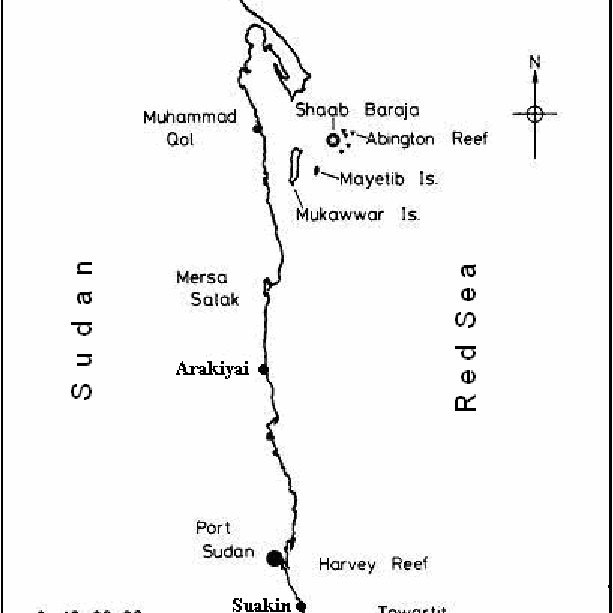

The location of a Russian Red Sea base remains up in the air, however. Sudan’s Red Sea Coast is little developed, largely due to a lack of suitable ports and an extreme shortage of fresh water that limits population concentrations. Coastal navigation is complicated by numerous shoals, rocky islands and a massive coral reef running parallel to the coast that limits the number of approaches. Russia appears to have been under the impression they could build their naval facilities near Port Sudan, which has rail and road connections to Khartoum, or at the historical port of Suakin, some 50 km south of Port Sudan with access to the same transportation network. Both ports are located near passages through the reef. Suakin was replaced by Port Sudan during the British occupation in 1909 when it proved unable to accommodate seagoing warships and freighters with a deep draft, though modern dredging has helped improve access. The Sudanese coastal navy operates out of Flamingo Bay, just north of the commercial docks in Port Sudan.

Beja Tribesmen Protesting in Port Sudan – The Flag is that of the Beja Congress (al-Arabiya)

Beja Tribesmen Protesting in Port Sudan – The Flag is that of the Beja Congress (al-Arabiya)

Port Sudan is located in Sudan’s unsettled Red Sea Province, where power struggles between the Hadendowa and Bani Amer branches of the Beja people have resulted in blockades of the Khartoum-Port Sudan highway and the closure of port terminals by protesters (Sudan Tribune, February 23, 2022). When Hemetti travelled to Port Sudan after his return from Moscow, he was met by large street protests partly inspired by local fears of a Russian takeover (Al-Jazeera, March 18, 2022).

Arakiyai – Port in the Middle of Nowhere (Map by Abdul-Razak M. Mohamed)

Arakiyai – Port in the Middle of Nowhere (Map by Abdul-Razak M. Mohamed)

Last year, Sudanese military authorities, eager for Russian arms and training but wary of a permanent Russian military presence in Sudan, instead suggested a Russian base at Arakiyai, a tiny fishing village with no infrastructure well north of Port Sudan and served only by a minor coastal road from the south (Radio Dabanga, December 7, 2021). The village is rarely even marked on maps. Constructing a new and isolated Russian base at Arakiyai from scratch would be far more difficult and expensive than incorporating existing infrastructure at Port Sudan. Ultimately, it would mean a delay of several years before the base could become operational.

The presence of a Russian nuclear-powered fleet in the Red Sea would ultimately be unacceptable to the West, which relies on free access to the Suez Canal at the sea’s northern end for shipments of oil, resources and commercial products bound for Europe and beyond. Saudi Arabia and other Gulf nations, wary of a Russian-Iranian axis in the region, also object to a Russian naval base on the Sudanese coast.

Outlook

It seems difficult to believe that the Sudanese junta would have mounted their coup without some kind of understanding from Russia that they would step in to replace the economic support Sudan was receiving from the West. Even in better times, however, it was never realistic to expect that Russian investments could make up for the billions of dollars of financial support suspended by the EU, the US and the IMF/World Bank after the military coup. Regardless of the outcome of the Ukraine conflict, Russia’s economy is shattered for years to come and their arms stocks are being drained by the fighting. There will be no largesse, military or financial, from Moscow’s direction for some years to come. Hemetti, with a nation of hungry and impoverished citizens looking for leadership, may discover his Russian gambit to avoid troublesome “Western interference” will be his downfall. Until a democratic civilian government is soon installed in Khartoum, Sudan will be hard pressed to find financial assistance unless it turns to China, another authoritarian state that will seek major concessions in return for economic and military support.

Hemetti, with his third-grade education and no background in economics or international relations, is playing a dangerous game by allying the junta with Russia and committing to the establishment of a Russian naval base in the strategically sensitive Red Sea. Moscow cares nothing for the quality of life in Sudan; the Wagner Group even less. Though Hemetti can count on the support of the paramilitary RSF, he does not necessarily have the backing of the officer corps of the Sudanese army, including the chief of the ruling Sovereign Council, General ‘Abd al-Fattah al-Burhan. Hemetti has essentially usurped the functions of Sudan’s foreign relations ministry, dealing with other nations on his own authority.

After Hemetti’s Moscow call, al-Burhan made a separate visit to his patrons in the United Arab Emirates, perhaps to shore up support in the event of a confrontation with Hemetti, who appears to be edging Sudan’s formal military leadership to the side. Hemetti’s rise and the inclusion of former Darfuri rebels in the Sudanese cabinet are indicators the growing political strength of Darfur’s Arab and indigenous African tribes in what has traditionally been the private reserve of the three great riverain Arab groups who live along the Nile north of Khartoum – the Ja’alin, the Danagla and the Sha’iqiya. Years of tribal manipulation and ruthless repression in Darfur (the source of most of the Sudanese Army’s manpower and most members of the RSF) are now coming back to haunt the riverain tribes who historically regard the peoples of Darfur as unsophisticated, uneducated and undeserving of political power.

The establishment of a naval base in the Red Sea was part of a greater Putin-inspired project to create an overseas presence as part of the foundation of a neo-Soviet Empire. However, Russia’s economic, diplomatic and military setbacks in its still unresolved conflict with Ukraine are almost certain to postpone, if not cancel, Russia’s imperial ambitions. In Sudan, Hemetti has succeeded in creating an independently financed security machine, but for the 44 million Sudanese who do not benefit from being part of the RSF, external relief and assistance is needed now. With almost daily demonstrations against military rule in Sudan, it is unlikely that brute force alone, even if aided by Russian mercenaries, will be enough to secure and sustain the military government.

Notes

- See: “Khartoum Struggles to Control its Controversial ‘Rapid Support Forces’,” Terrorism Monitor, May 30, 2014, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=852

- The Security Service of Ukraine (Sluzhba bezpeky Ukrayiny – SBU) claimed in 2019 to have copies of the personal documents of 149 Wagner Group mercenaries who travelled to Sudan on Russian Ministry of Defense airliners to suppress pro-democracy protests in 2019 (info, Gordonua.com, January 28). See: “Russian Mercenaries and the Survival of the Sudanese Regime,” Eurasian Daily Monitor, February 6, 2019, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4356

- See: “Russia’s Arms Sales to Sudan a First Step in Return to Africa: Part One, Eurasian Daily Monitor, February 11, 2009, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=2593 ; Part Two, Eurasia Daily Monitor, February 12, 2009, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=2596

- See: “Will Khartoum’s Appeal to Putin for Arms and Protection Bring Russian Naval Bases to the Red Sea?” Eurasia Daily Monitor, December 6, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=4081

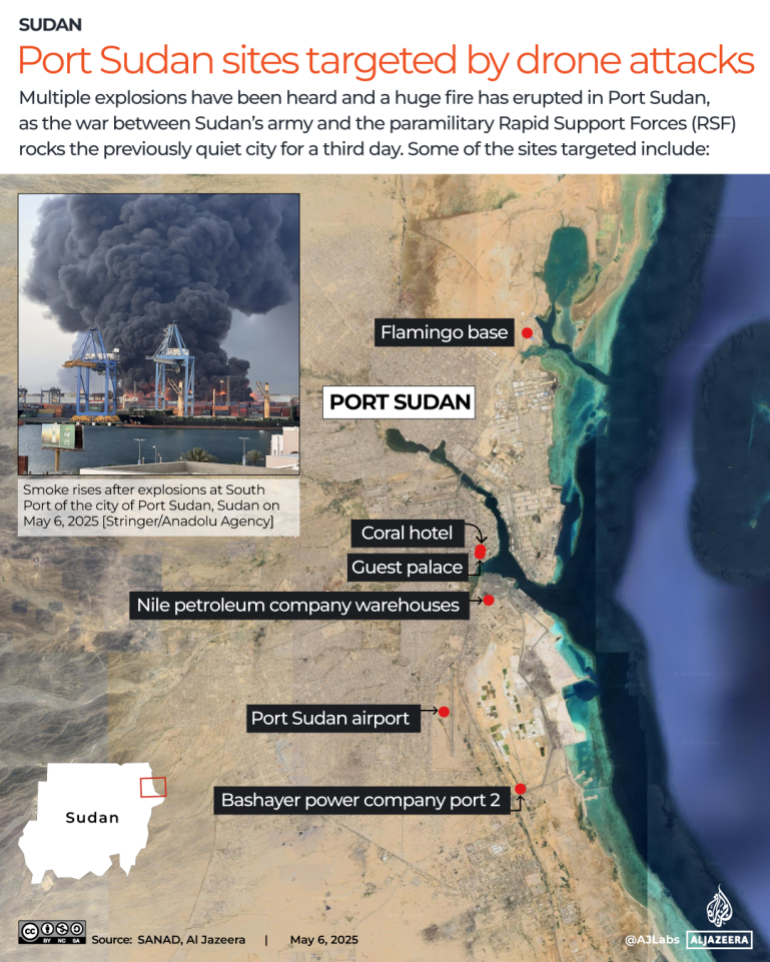

Fuel depot in Port Sudan burns after drone attack, May 5, 2025 (Xinhua).

Fuel depot in Port Sudan burns after drone attack, May 5, 2025 (Xinhua). General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, May 6, 2025 (Sudan Tribune)

General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan, May 6, 2025 (Sudan Tribune) Flamingo Bay naval facility, north of Port Sudan (GoogleEarth)

Flamingo Bay naval facility, north of Port Sudan (GoogleEarth) Osman Digna military airport in flames, May 4, 2025

Osman Digna military airport in flames, May 4, 2025 An indefinite delay in the construction of a Russian naval facility at Port Sudan due to the attacks will likely jeopardize the Sudanese state’s planned acquisition of Russian warplanes, such as the Su-30 and Su-35, in exchange for the use of the port. The potential loss of Russian interest in Sudan could work in the PRC’s interest. Even though PRC-made drones caused the damage to Port Sudan, the Sudanese state (TSC/SAF) has only blamed the intermediary supplier, the UAE. If Russia backs off from the port deal and its reciprocal arms supplies, Beijing may be able to step in to make arrangements with the Sudanese state (TSC/SAF).

An indefinite delay in the construction of a Russian naval facility at Port Sudan due to the attacks will likely jeopardize the Sudanese state’s planned acquisition of Russian warplanes, such as the Su-30 and Su-35, in exchange for the use of the port. The potential loss of Russian interest in Sudan could work in the PRC’s interest. Even though PRC-made drones caused the damage to Port Sudan, the Sudanese state (TSC/SAF) has only blamed the intermediary supplier, the UAE. If Russia backs off from the port deal and its reciprocal arms supplies, Beijing may be able to step in to make arrangements with the Sudanese state (TSC/SAF).