Andrew McGregor

July 14, 2004

“Now is the Time of the Assassins” – Arthur Rimbaud

The February 13 assassination in Qatar of former Chechen President Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev by Russian agents is one of many challenges to international law posed by the new tactics of the “War on Terrorism.” America’s doctrine of preemptive “defensive” use of force has been enthusiastically taken up by several other powers, including Russia, which announced its own policy on the preemptive use of military force in the case of “direct threats” to Russia in October 2003. Unfortunately the definition of justified pre-emptive action depends on the national interests of each nation-state, as does the identification of individuals as “terrorists,” a prescription for inevitable conflict. The consequences of reinterpreting international law were recently displayed at the trial of Yandarbiyev’s assassins in petroleum-rich Qatar, base of operations for U.S. Central Command during the Iraq campaign.

Zelimkkhan Yandarbiyev (Reuters)

Zelimkkhan Yandarbiyev (Reuters)

A Theorist of Jihad

Yandarbiyev, 52 at his death, was born in Kazakhstan during the years of Stalin’s exile of the Chechen nation. A poet and children’s author, Yandarbiyev became a leader in the Chechen nationalist movement as the Soviet Union began to collapse. During the 1994-96 war, Yandarbiyev had little connection with military operations, spending his time writing books on the independence effort. After the Chechens retook Grozny, Yandarbiyev helped negotiate the war-ending Khasavyurt Accords, shocking Boris Yeltsin by his insistence that the Chechen delegation be accorded equal status with Russia at the negotiations. It was the high point in his struggle for Chechen independence.

Yandarbiyev served as President of Chechnya from April 1996 to January 1997 after the assassination by targeted missile of his predecessor, Djokar Dudayev. His vision of an Islamic Chechnya was soundly rejected in the Presidential elections of 1997, in which he placed a distant third. In the second Chechen war, Yandarbiyev was assigned as Chechen representative in the Gulf because of his “authority and connections” in the region.

In his appearances on al-Jazeera TV and elsewhere, Yandarbiyev grew increasingly dismissive of appeals to the West for moral or material support for the Chechen cause. It was his belief that all Muslim nations should provide the Chechen jihad with military as well as humanitarian assistance in support of “Chechnya as an independent Islamic state.” [1] After numerous disagreements with Maskhadov, Yandarbiyev dissociated himself from the government in November 2002, calling for less restraint in the methods used in the “national liberation struggle.” Living in Qatar as a guest of its ruler, Emir al-Thani, Yandarbiyev wrote extensively on his radical interpretation of the theory of jihad, including the books Whose Caliphate? and Jihad and Problems of the Contemporary World.

Yandarbiyev’s attempts to gather official Arab and Muslim support for Chechen aspirations were largely unsuccessful, save for recognition of Chechen independence by the Taliban government of Afghanistan. This effort was unappreciated by Maskhadov, who refused to give his approval. Hindered further by Russia’s warnings to Muslim states that a visit from Yandarbiyev would be regarded as “a hostile act,” Yandarbiyev spent much of his time writing in his Qatar villa. Russia made the first of several requests for extradition in February 2003, citing Yandarbiyev as a major international terrorist and financier of the “al-Qaeda backed” Chechen resistance.

In June 2003, Yandarbiyev was placed on the UN Security Council’s blacklist of al-Qaeda-related terrorist suspects. By the terms of the UN’s decision all member states were called upon to freeze funds, ban financial support, and prevent the entry of Yandarbiyev to their countries. Yandarbiyev expressed outrage at the listing: “I should say that those trying to label me as a terrorist showed what they are, by agreeing with the most dirty and inhumane stronghold of international terrorism and criminal activity, such as is Russia today in its criminal military-political regime.” [2]

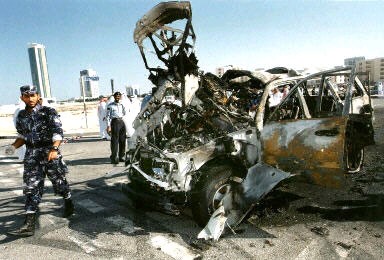

On February 13, 2004, a car bomb killed Yandarbiyev and badly injured his young son. In Grozny, the newly “elected” Russian-backed President Akhmad Kadyrov declared that no one in Chechnya would regret Yandarbiyev’s fate. A few months later, Kadyrov would himself be victim of an assassin’s bomb.

A Trial of Two Agents

After the bombing there were many in Russia who were willing to give the opinion that Yandarbiyev was the victim of a traditional Chechen blood vendetta or Mujahideen angry at alleged misappropriation of funds. The most creative explanation of his death came from the Headquarters of Russian forces in the Caucasus, suggesting that Yandarbiyev was the victim of angry Azerbaijani book-publishers who had lost money on his “anti-Russian” books. [3]

Yandarbiyev’s Van after the Bombing (Middle East Online)

Yandarbiyev’s Van after the Bombing (Middle East Online)

The arrests occurred at a villa rented for the Russian agents some distance from the Russian Embassy. Alexander Fetisov, First Secretary of the Embassy, claimed diplomatic immunity and was eventually released. For the others, the future looked grim; there were witnesses, bomb-making materials seized from the villa, and the Qataris had recordings of all their cell-phone traffic. Convinced that they had been abandoned to their fate, the two agents gave detailed confessions. These were later withdrawn when a team of top Russian lawyers arrived to defend them, but despite Russian allegations that the statements were the result of torture, they were accepted into evidence. Efforts to claim the villa as Russian diplomatic territory to force the exclusion of evidence taken there were also unsuccessful.

Many leading Russian politicians called for the use of military force to release the suspects. One proposal called for Qatar to be targeted by dummy missiles, with real ones to follow if the agents were not released. Other politicians hinted at American responsibility for the assassination; according to Duma Deputy Nikolai Leonov (a 33 year veteran of Russian intelligence), “There is only one country in the world today, which widely practices political murders – it’s the USA. Moreover, this activity is completely legal there – there is this special President’s Decree, which permits them to conduct such ‘special operations’.” [4] Russia had actually threatened to rescue the agents with a Special Forces operation – an act of madness considering the concentration of U.S. forces in the tiny Emirate. [5]

A senior U.S. diplomat admitted that the U.S. had rendered ” very insignificant technical assistance” to Qatar in the apprehension of the Russian agents, [6] apparently in the form of “a small team of experts in the technical aspects of explosives.” [7] The head of the Russian team of lawyers alleged that investigation records had been doctored to omit American involvement. [8]

In a return to the methods of the Cold War, two members of the Qatar wrestling team were arrested on February 26 for alleged currency violations while changing planes in Moscow. Their detention sparked predictable outrage in Qatar. The wrestlers were released a month later when Fetisov was allowed to return to Russia. Shortly after, a Russian spokesman made the surprising and unsubstantiated charge that Yandarbiyev was responsible for the 1996 attack on a Red Cross hospital in Noviye Atagi in which six international workers were murdered.

The Russian position was consistent throughout the trial: the agents “stayed in Qatar legally and carried out informational and analytical tasks related to the fight against international terrorism without any violation of the local legislation.” [9] Foreign Minister Lavrov pointed to Russia’s condemnation of the assassination of Hamas leader Shaykh Yassin as proof of Russia’s rejection of extrajudicial punishments. As the verdict approached, the Kremlin made a surprising show of clemency itself, releasing seven alleged Russian Taliban members [10] recently transferred from Guantanamo Bay – despite an understanding with the U.S. that the prisoners would be prosecuted on their return to Russia.

On June 30, the Russians were found guilty of carrying out a murder “ordered by the Russian leadership.” Chechen rebels declared that the verdict had finally shown “who is the terrorist and who is the victim of terror.” [11] Yandarbiyev’s widow is now seeking to have his UN terrorist designation reversed posthumously. A pardon for the killers remains uncertain; the murder was an enormous affront to the personal dignity of the Emir. Yandarbiyev was buried in the royal family’s cemetery, and praised as a “holy warrior for Islam.”

The Tactic of Assassination

U.S. Pentagon officials began to consider the use of assassination in 2002 as part of a boundary-less War on Terrorism, unhindered by Ronald Reagan’s Executive Order 12333 against the use of such tactics. Press reports cited Israeli cooperation in training U.S. Special Forces to carry out “extrajudicial punishments.” [12] Assassination is widely accepted as being prohibited by two international agreements:

1) Regulations annexed to the Hague Convention IV (1907), in which it is forbidden to “kill or wound treacherously individuals belonging to the hostile nation or army,” and

2) The Geneva Conventions on the Law of War, Common Article 3, which prohibits “the passing of sentences and the carrying out of executions without previous judgment pronounced by a regularly constituted court.”

Nevertheless, there are many members of the current U.S. administration who believe that these agreements and related executive orders have no application in the War on Terrorism. Some legal experts have argued that Article 51 of the UN Charter allows for “anticipatory” self-defense, though others argue that the Charter refers only to nation-states and not individuals. After the November 2002 assassination of al-Qaeda leader Qaed al-Harthi and five compatriots in Yemen by the missiles of a CIA Predator unmanned aircraft, U.S. National Security Advisor Condaleeza Rice maintained that President Bush was “well within the bounds of accepted practice and the letter of his constitutional authority.” [13] When authority to launch similar strikes was passed to various members of the administration, assassination found new legitimacy as a tactic in the War on Terrorism.

When asked if Russia had the right to kill terrorists on foreign territory, Russia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs referred to U.S. and Israeli precedents: “This is a conceptual question, connected with actions of Israel against Palestinian terrorists, and also by actions against the Taliban in Afghanistan, al-Qaeda, (and) the overthrow of Saddam Hussein’s regime in Iraq. This question shouldn’t be put to Russia.” [14]

Conclusion

The Yandarbiyev case is an important milestone in the renegade approach to the War on Terrorism. The boldness with which Russia carried out its operation in the midst of sensitive U.S. military installations suggests that America may have acquired a “rogue-partner” in the war on terror. Hopefully the case will act as proof that the targeting of individuals given political refuge in third-party countries is counter-productive. The verdict also begs a clarification from the United States on its own pre-emptive policies, so often cited by Russia and others as the inspiration for their own campaigns of targeted killings. The UN must also make it clear whether the Security Council’s blacklist is also a “hit-list.” The alternative is a future in which assassination squads roam the world’s capitals, leaving murder and mayhem in their wake in the name of the “War on Terrorism.” It is the choice between an era of international law, or the “Time of the Assassins.”

Notes

- “War, unleashed in Georgia and Azerbaijan 12 years ago, has not ended” [Interview with Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev], Zerkalo (Azerbaijan), Sept.24, 2002.

- “Exclusive interview of the ex-president of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev with the Daymohk News Agency,” July 15, 2004, www.daymohk.info/rus/index.php.

- Ilya Shabalkin, quoted in: “Former Chechen rebel leader killed for $200,000,” Gazeta.ru, Feb.16, 2004.

- Olga Kultonova: Nikolai Leonov: “Only Americans could kill Yandarbiyev,” Feb.29, 2004, www.newsinfo.ru.

- Michael Binyon and Jeremy Page: “Qatar bombers ‘were Russian special forces’,” The Times (London), March 12, 2004.

- Andrey Zlobin: “Interview with Steven Pifer [U.S. Deputy Assistant for European and Eurasian Affairs],” Vremya Novostey no.47, March 22, 2004, www.vremya.ru/2004/47/5/94450.html.

- Anatoly Medetsky: “U.S. helped Qatar make the arrests,” Moscow Times, March 23, 2004.

- Mikhail Zygar: “They have inquisitional trial” [Interview with Dmitriy Afanasyev], Kommersant no.77, April 28, 2004.

- Yuri Zinin: “Russians on trial in Qatar feel ‘normal’, says Russian embassy,” RIA Novosti, June 28, 2004.

- Andrew McGregor: “From Russia to Cuba: The Journey of the Russian Taliban,” Central Asia – Caucasus Analyst (Central Asia Caucasus Institute – Johns Hopkins University), July 16, 2003, www.cacianalyst.org/view_article.php.

- Akhmad Zakayev, quoted in Andrew Hammond, “Qatar court jails Russians over Chechen killing,” Reuters, June 30, 2004: Nearly identical comments were made by Shamyl Basayev: “Chechen warlord says won’t hurt Russians abroad –TV,” Reuters, July 2, 2004.

- Julian Borger: “Israel trains U.S. assassination squads in Iraq,” The Guardian, Dec.9, 2003.

- “Bush gives nod to more attacks on terrorists,” Reuters, Nov.11, 2002.

- MFA Sergey Lavrov, quoted in: “Yandarbiev assassination: No Russian connection, says Foreign Minister,” RIA Novosti (Moscow), March 18, 2004.

This article was first published in the July 14, 2004 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.