Andrew McGregor

Terrorism Monitor, November 17, 2011

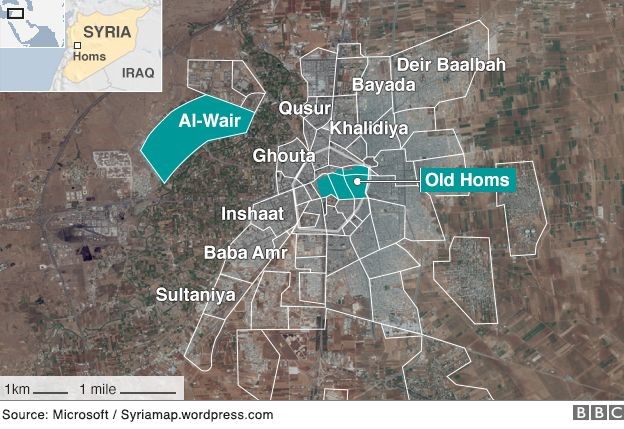

The Syrian revolt against the Assad regime has been particularly intense in the city of Homs, as has been the regime’s violent response. Homs-based opposition leader and self-described “field coordinator of the revolution in Homs” Husayn Iryan recently described resistance operations in Homs in an interview with a pan-Arab daily (al-Sharq al-Awsat, November 12). An industrial city of 1.5 million, Homs is located 160 km north of Damascus. The majority of its residents are Sunni Muslims, though there are significant minorities of Alawis and Christians. Armed clashes began in Homs in May, with the anti-regime Free Syrian Army launching operations in Homs in October.

Iryan presents an optimistic evaluation of the resistance efforts in Homs despite the daily “horrible crimes and massacres” perpetrated by the regime in that city: “Homs has managed in the last weeks to exhaust the Syrian regime and to weaken it to the extreme limits through non-stop protest movements despite all the restrictions, the siege and the massacres that the regime commits in the city against its sons.”

Iryan presents an optimistic evaluation of the resistance efforts in Homs despite the daily “horrible crimes and massacres” perpetrated by the regime in that city: “Homs has managed in the last weeks to exhaust the Syrian regime and to weaken it to the extreme limits through non-stop protest movements despite all the restrictions, the siege and the massacres that the regime commits in the city against its sons.”

Iryan explains the viciousness of the regime’s crackdown on the opposition in Homs by pointing to four factors:

- The city’s proximity to Lebanon and the government’s fears that this might enable Homs to become “like Benghazi” and slip from the regime’s control.

- The Khalid bin al-Walid battalion of the armed opposition was formed in Homs, where splits in the regular army first occurred. The battalion, named for the 7th century Arab conqueror of Syria, is active in resisting the ongoing siege by loyalist forces. The formation of a second battalion of defectors called the Ali bin Abi Taleb Battalion (under the supervision of the Khalid bin al-Walid Battalion) was announced in the Homs Province city of Houla in late September (al-Jazeera, September 27).

- Homs was the first city to initiate civil disobedience, with citizens refusing to pay taxes and civil servants refusing to carry out their work.

- Revolutionary forces in Homs have inflicted casualties on the army, the intelligence services and government-sponsored “thugs” in the last few months.

For this resistance, Iryan says Homs, al-Qusayr and other towns and villages in the Homs Province had collectively suffered over a thousand dead, many of these consigned to mass graves. According to Iryan, even flight from Homs has become impossible due to the government cordon around the city: “Those who enter Homs can consider themselves doomed and those who manage to leave it consider that they have been given a new life.”

Unlike the militancy of the Homs opposition, a vastly different assessment of the Syrian revolution came in an interview with Hasan Abd-al-Azim, the general coordinator of the National Coordination Committee for Democratic Change in Syria. Al-Azim’s committee represents some fifteen political parties, including Arab leftist groups and some Kurdish political parties: “We have parties whose hands are not covered in blood and corruption. We are hoping to have a pluralistic, parliamentary, and democratic state and a new system that satisfies all the aspirations of the Syrian people…”

Syrian Government Patrol in Homs, 2013 (BBC)

Syrian Government Patrol in Homs, 2013 (BBC)

Al-Azim, whose movement favors an “Arab solution” and opposes foreign intervention or the imposition of a no-fly zone, speaks of a “peaceful revolution in Syria which has not used weapons or violence as Al-Asad’s regime is claiming” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, November 11). In asserting the possibility that real change can be brought about in Syria by peaceful protest, al-Azim overlooks numerous reports of violence and the attempted assassination of the Yemeni president to cite “the peaceful Yemeni revolution that has entered its tenth month without the people using weapons, though weapons in Yemen are available in all houses and streets.”

A veteran of various left-wing Arab nationalist parties, Abdul Azim has rejected a militant approach to the resistance, backing a moderate package of reforms leading to democracy that does not necessarily involve overthrowing the Assad regime (al-Akhbar [Beirut], September 21).

The disparate approaches to revolution in Syria in these two statements reflect the wider divisions that have plagued the Syrian opposition, differences that boiled over when some Syrian opposition figures were assaulted by other opposition members when they tried to enter the headquarters of the Arab League in Cairo for a meeting with the League’s secretary-general (al-Quds al-Arabi, November 11).

This article first appeared in the November 17, 2011 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.