Andrew McGregor

Integrity Initiative, Institute for Statecraft (UK), November 12, 2018

The approach of the Italian-hosted November 12-13 Palermo Conference on Libya has seen dire but largely unsubstantiated reports of Russian Special Forces, mercenaries and intelligence officers arriving in eastern Libya, together with advanced weapons systems aimed at NATO’s soft southern underbelly. Their alleged intention is to control the flow of migrants, oil and gas to Europe as a means of undermining European security. The full accuracy of these reports is questionable, but there is little question that Russia is deeply engaged in reasserting its influence in Libya, as well as other North African nations that once had close ties to Soviet Moscow.

Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar (Algeriepatriotique)

Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar (Algeriepatriotique)

The task is far from simple; in Libya, Russian emissaries must deal with Libya’s competing governments, the Tripoli-based and internationally-recognized Presidency Council and Government of National Accord (PC/GNA) and the Tobruk-based House of Representatives (HoR). In practice, Moscow has dealt most closely with a third party, the Libyan National Army (LNA) led by “Field Marshal” Khalifa Haftar. Though nominally at the service of the HoR, the LNA is actually a coalition of former revolutionaries, mercenaries and Salafist militias under the independent command of Haftar and his family. The LNA controls eastern Libya (Cyrenaïca) and much of the resource-rich south.

While the Trump administration has indicated its disinterest in Libya in particular and Africa in general, Italy is also trying to reassert influence in its former Libyan colony, a project that is made more difficult by the contradictions created by the pro-Russian sympathies of the Italian government.

Russian Interests in Libya

Russia’s point man in Libya is Lev Dengov, a Chechen businessman and head of the Russian Contact Group for intra-Libyan settlement. According to Dengov, Moscow’s interaction with Libyan leaders is only part of an effort to restore economic ties with Libya. He denies that Russia supports any one side in the ongoing conflict.

Moscow does not deny the presence in Libya of Russian private military contractors (a modern euphemism for organized mercenary groups), but insists their presence is for legitimate security reasons unrelated to Russian foreign policy objectives.

Russia’s Tatneft oil and gas company is in talks with the Libyan National Oil Corporation (NOC) to resume operations within Libya that were brought to a halt by the 2011 revolution. The NOC operates independently of Libya’s rival governments but its facilities are often targeted by a broad variety of armed groups. Russia is also in talks to resume construction of the Sirte-Benghazi railway, a $2.5 billion project that was brought to an abrupt halt by the 2011 revolution.

A potential means for Russia to wield influence in Europe could come through domination of the Greenstream natural gas pipeline that carries 11 billion cubic meters of gas per year from Libya to Europe. Russia is already the largest exporter of oil and natural gas to the European Union; further influence over energy flows to Europe would place Moscow in a strong position in its dealings with Europe.

According to LNA spokesman Ahmad al-Mismari, Libyans admire Russia as a “tough ally.” Al-Mismari also noted that most senior officers in Libya were trained in Russia and that Moscow was providing medical treatment for at least 30 injured LNA fighters.

Haftar has visited Moscow three times and was welcomed off Libya’s coast for talks with the Russian Defense Minister aboard Russia’s sole aircraft carrier in January 2017. Haftar is eager to have the 2011 UN arms embargo removed in order to resume shipments of Russian arms as part of a $4.4 billion contract signed before the revolution.

Italian Relations with Russia

Italy is increasingly at odds with its EU partners over sanctions imposed on Russia in 2014 after the Russian annexation of the Crimea and its support for ethnic-Russian separatists in eastern Ukraine. The partners in Italy’s governing coalition are the League (Lega) Party and the Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle). Both are broadly pro-Russian and Euro-skeptic.

In a mid-October visit to Moscow, Italian Interior Minister Matteo Salvini denounced the sanctions as “social, cultural and economic madness.” Prime Minister Giusseppe Conte is in agreement, calling the sanctions “an instrument that would be better left behind.” Salvini’s League Party is close to Moscow, having signed a cooperation deal last year with United Russia, Russia’s ruling party.

However, the Italian government is not blindly pro-Moscow or oblivious to its own interests; on October 26, Prime Minister Conte gave the long disputed go-ahead to the Italian portion of the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline, a $5 billion project designed to relieve Europe’s dependency on Russian natural gas.

Italian Forces on the Libyan Border

Il Mediterraneo Allargato (Riccardo Piroddi)

Il Mediterraneo Allargato (Riccardo Piroddi)

Italy’s January decision to reassign troops from its missions in Iraq and Afghanistan to Niger and Libya is, in part, a reflection of a new emphasis on what Rome calls il Mediterraneo allargato, “the enlarged Mediterranean.” According to Defense Minister Roberta Pinotti, in this reshaping of strategic interests, “the heart of our interventions is the enlarged Mediterranean, from the Balkans to the Sahel, to the Horn of Africa.”

Italy has a small military presence in Libya, consisting of support elements for the Libyan Coast Guard (at least the part under the authority of the PC/GNA) and a military hospital in Misrata also acts as a military observation post. The Italian military presence in Italy was the subject of protests in several Libyan cities in July 2017.

After an eight-month delay, Italian defense minister Elizabetta Trenta announced the Italian mission to Niger, Operation Deserto Rosso, was ready to implement its mandate of stemming illegal migrant flows to Europe by providing training to Nigérien security forces patrolling the routes used by human traffickers and terrorists. Trenta added that, “for the first time, we in Italy begin to calibrate our own missions according to our own interests.”

Colonial Era Fort at Madama, Niger (Defense.gouv.fr)

Colonial Era Fort at Madama, Niger (Defense.gouv.fr)

At full strength, the Italian mission will consist of 470 troops, 130 vehicles and two aircraft. The mission is intended to be divided between Niger’s capital of Niamey and Madama, site of a colonial-era French Foreign Legion fort close to major smuggling routes near the Libyan border. There is no combat element to the Italian mission, which will focus on training Nigérien personnel rather than acting as “sentinels on the borders.”

Does Russia Intend to Control Migration Flows through Libya to Europe?

Rumors of Russian intention of building a naval base at the LNA-controlled deep-water ports of Tobruk or Benghazi began to circulate in January. Russian experts were reported to have visited the port several times to check conditions there. Initial Russian denials were followed in February by Lev Dengov’s claim that documented evidence existed at the Russian Defense Ministry proving Haftar had asked Russia to construct a military base in eastern Libya.

On October 8, the Sun, a UK tabloid better known for its “page 3” girls than cutting edge coverage of international issues, published an article claiming British Prime Minister Elizabeth May had been warned by British intelligence chiefs that Russia intended to make Libya a “new Syria.” Without revealing its source, the tabloid further claimed that members of the GRU (Russian military intelligence), Spetznaz Special Forces and private military contractors from the Russian Wagner Group were already on the ground in eastern Libya, where they were alleged to have set up two military bases. The Sun claimed their primary goal was “seizing control of the biggest illegal immigration route to Europe.”

Arriving with the military personnel were Russian-made Kalibr anti-ship missiles and S-300 air defense missile systems. The Russians were said to be providing training and “heavy equipment” to Haftar’s LNA. An unnamed senior Whitehall source warned that the UK was “extremely vulnerable to both immigration flows and oil shock from Libya,” calling the alleged Russian deployment “a potentially catastrophic move to allow [Vladimir Putin] to undermine Western democracy.”

The Sun report emerged only three days after the UK’s Sunday Times revealed that the British military was war-gaming a cyber-attack on Russia based on a scenario in which Russia seizes Libya’s oil reserves and launches waves of African migrants towards Europe.

The deployment of advanced weapons systems in Libya in defiance of the UN arms embargo and in full knowledge that such a deployment would be regarded by NATO as a major provocation makes that part of the Sun story unlikely. Such systems would only have value as protection for a Russian base that, as of yet, does not exist. Haftar’s LNA is not under threat from either the sea or the air and has little need for such weapons.

Some of the Sun’s account appears to follow from an earlier but unverified report that dozens of mercenaries from the Russian RBC Group had been operating in eastern Libya since March 2017. This account appeared (without sources) in the Washington Times, a daily owned by Reverend Sun Myung Moon’s Unification Church. The article claimed the mercenaries were doing advance work for the establishment of a Russian military base in either Tobruk or Benghazi.

Lev Dengov suggested the Sun’s report could be an attempt to undermine the Palermo Conference, noting that “all reports about the Russian military presence in Libya, without exception, come from non-Libyan sources. How can it happen that no Libyan has ever noticed their presence?”

The deputy chair of the defense committee of the Russian Federal Assembly’s upper house described the Sun’s report as an attempt to discredit Russia’s war on terrorism: “There are no [Russian] military servicemen [in Libya] and their presence is not planned. How could they be there without official request by the country’s authorities?” Asharq al-Awsat, a prominent London-based Arabic daily, said that a number of Libyan deputies had told them there were no Russian bases in Benghazi or Tobruk.

The Russian Foreign Ministry said the Sun’s article was “written in a glaringly alarmist style, with the aim to intimidate the common British reader [with] a mythical Russian military threat.” Nonetheless, Russia’s RBC Media said a source within the Defense Ministry had confirmed the presence in eastern Libya of troops from elite Russian airborne units, though their numbers and mission was unclear.

Conclusion

Manipulating migration flows would require a continuous state of insecurity in Libya. A unified Libyan state could not possibly benefit (as militias and armed gangs do) from allowing mass migration from sub-Saharan states into Europe via Libya. As noted in the HoR agenda for the Palermo conference, illegal migration has led only to “the spread of organized crime, terrorism, looting and the smuggling overseas of the country’s assets.”

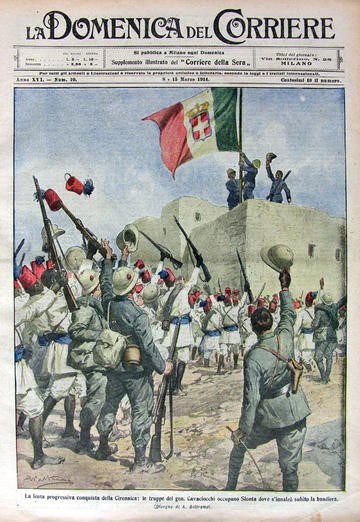

The 75-year-old Haftar, a US citizen, long-time CIA asset and alleged war-criminal who has spent much of his life outside of Libya, has had major health issues in the last year and is far from a secure bet to take power in Libya. Haftar has tried to devolve power onto his sons, but they enjoy little popular support. The LNA, a loose coalition or militias rather than an army, is likely to dissolve upon Haftar’s death into battling factions. This is factored into Moscow’s cautious approach in Libya, which is carried out simultaneous with probes (possibly including disinformation) to determine what activities the Western Alliance will tolerate there. Russia’s affinity for strongman types suggests that Moscow may have quietly thrown its support behind the aging Haftar while still keeping channels open with the ineffective but internationally recognized PC/GNA government in Tripoli. Italian and Eritrean colonial troops celebrate a victory in the conquest of Libya

Italian and Eritrean colonial troops celebrate a victory in the conquest of Libya

Sovereignty is, and will remain, a sensitive issue in Libya, which suffered through brutal and exploitative occupation by Italian imperialists and later by Italian fascists. Even the Soviet Union was unable to get Mu’amar Qaddafi to agree to allow a Soviet naval base in Libya. Any perception that Haftar is willing to sacrifice Libyan sovereignty without legal authority for the benefit of himself and his family will do little to broaden his support in Libya.

Italy’s decision to work counter to the sanctions applied against Russia by the West will in turn encourage greater Russian expansion into Italy’s strategically defined “Enlarged Mediterranean.” Russia intends to build a sphere of influence extending through Libya, Egypt and Sudan, a strategic feat that is being accomplished through the disinterest of the United States and the acquiescence of NATO partners like Italy, which continues to struggle to reconcile Russian interests with its own.