Andrew McGregor

September 27, 2012

For decades one of Egypt’s most violent extremist groups, al-Gama’a al-Islamiya (GI) is currently engaged in a struggle to establish itself as an Islamist political party in post-revolutionary Egypt. Though traditionally a Salafist-Jihadi movement, GI has not established close relations with al-Nur, the largest of Egypt’s Salafist political parties. Nor is it close to the Muslim Brotherhood, which recently ignored the movement in the distribution of senior government posts.

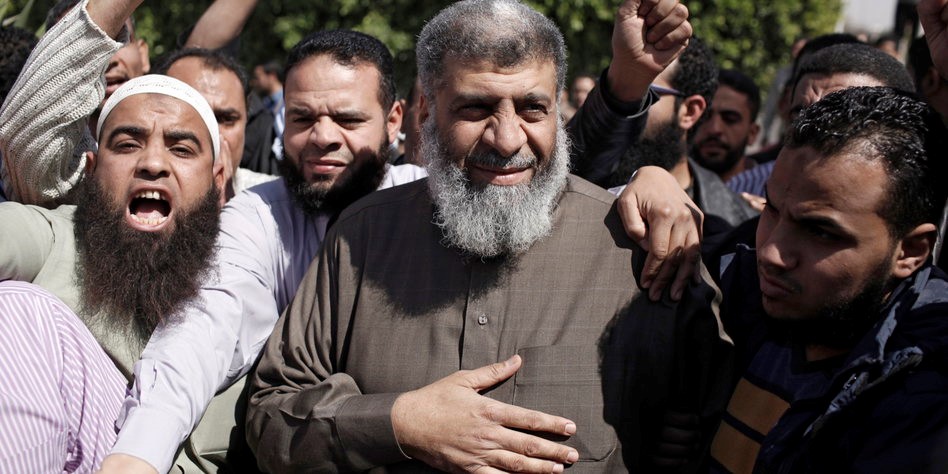

Al-Gama’a al-Islamiya Spokesman Assem Abd al-Maged

Al-Gama’a al-Islamiya Spokesman Assem Abd al-Maged

On September 17, a GI spokesman announced that the movement had formed “al-Ansar,” a new movement drawing on young people of various Islamist trends to protect the reputation of the Prophet Muhammad by producing films about Christianity and Judaism and starting a publishing house and satellite channel to support this effort (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], September 17).

While the movement continues to work on its conversion to a political party, it appears not to have abandoned its commitment to jihad, at least beyond Egypt’s borders. GI spokesman Assem Abd al-Maged has stated that GI members were travelling to Syria to join the anti-Assad revolt and that three Egyptians affiliated to the movement were recently killed in battle in Syria. A spokesman for the Free Syrian Army (FSA) confirmed the participation of Egyptians in the armed opposition but noted that these fighters had not revealed their political affiliations (Anadolu Ajansi [Ankara], September 8; al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], August 26; September 9). The GI has also attempted to insert itself into the security crisis in the Sinai by sending a delegation to meet with tribal and religious leaders in the region in early September (Al-Ahram Weekly, August 30 – September 5).

The GI is taking a hard stand on Egyptian-American relations, having urged Egyptian president Muhammad Mursi to cancel his September 23 visit to the United States to address the United Nations. Suggesting that the anti-Islamic film The Innocence of Muslims was made under “American auspices,” GI spokesman Assem Abd al-Maged argued that Egypt did not need to worry about U.S. cuts in aid to Egypt as such cuts were “not in [the United States’] interest, as they know we are the superpower in the region” (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], September 16).

According to an official with the GI’s political wing, the Building and Development Party, the movement is prepared to sever its alliance with the Muslim Brotherhood’s Freedom and Justice Party following President Mursi’s failure to include GI members as presidential advisors, regional governors or members of the National Human Rights Council. The group was especially disturbed by its omission from the latter body, noting that the GI was “the faction persecuted most by the former regime, with 30,000 members having been arrested and 20 of them having died in prison due to torture and diseases” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, September 9; al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], September 9). There has been some speculation in Egypt that the recent protests at the U.S. Embassy had less to do with anger over the anti-Muslim film than with an opportunity to embarrass the Mursi government after it failed to include the GI in the new government.

Though the Brothers may not be offering much in the way of political appointments, some veteran members of the GI are enjoying a bit of revisionary justice under the new regime. President Mursi pardoned 26 members of GI and its Islamic Jihad offshoot in July. Four members of GI who were sentenced to death in 1999 during Mubarak’s rule were released on September 5 pending a ruling in early November on their case. The four were among 43 Egyptians returned to Egypt through the CIA’s “extraordinary rendition” program after being sentenced to death in absentia in the “Albanian Returnees” case of 1999 (Ahram Online, September 5; al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], September 7). The GI members had been charged with attempting to overthrow the government, killing civilians and targeting Christians and the tourism industry.

One of those released, Ahmad Refa’i Taha (indicted in the United States for his role in the 1999 U.S. Embassy bombings in East Africa) has demanded an immediate pardon rather than wait for the November ruling, describing the case as “a huge insult to the revolution and revolutionaries…We are considered the first to fight the former regime, which nobody revolted against like us… We would like people to have shown some appreciation for those who opposed Mubarak and his regime” (al-Hayat, September 7).

Demands by the GI and other Islamist groups in Egypt and Libya for the release of former GI leader Shaykh Omar Abd al-Rahman from an American prison (where he is serving a life-term for his role in the 1993 World Trade Center bombing) have been supported by President Mursi, who has asked for the shaykh’s release on humanitarian grounds.

In the coming parliamentary elections, GI may seek to capitalize on growing rifts within al-Nur, the largest of the Salafist political parties (Ahram Online, September 25). According to GI leader Aboud al-Zomor, the movement will seek to form new alliances prior to the elections and is determined to increase the handful of seats won in last year’s contest (al-Masry al-Youm [Cairo], August 30). Aboud and his brother Tarek, both prominent GI leaders, were released from prison in March, 2011 after having been convicted in 1984 for their admitted roles in planning the assassination of former Egyptian president Anwar al-Sadat. Aboud has since apologized, not for killing Sadat, but for creating the conditions that led to Hosni Mubarak’s authoritarian 30-year rule.

This article first appeared in the September 27, 2012 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor.