Andrew McGregor

March 10, 2011

Beyond the battle for the towns and cities of Libya, there is another battle raging over the legacy of Sidi Omar al-Mukhtar, Libya’s “Lion of the Desert.” The symbol of Libyan nationalism and pride, the inheritance of this stalwart of the Islamic and anti-colonial struggle against Italian fascism has been cited as the inspiration of both the Qaddafi regime and the rebels who oppose it. Al-Mukhtar’s heritage is also cited by the foreign Islamists who would seek to influence events in Libya.

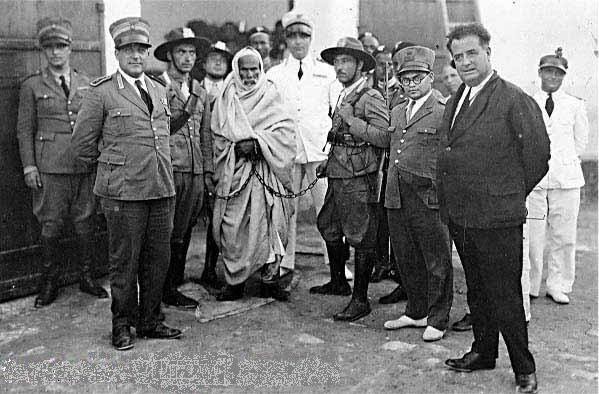

Omar al-Mukhtar in Chains After his Arrest by Italian Officials

Omar al-Mukhtar in Chains After his Arrest by Italian Officials

Omar al-Mukhtar and the Roman Riconquista

An Islamic scholar turned guerrilla fighter, Omar al-Mukhtar was a member of the Minifa, a tribe of Arabized Berbers. Educated in the schools of the powerful Sanusi Sufi order, al-Mukhtar joined the Sanusi resistance to the Italian invasion of Libya in 1911. Unable to control little more than the coastal strip, the Italians turned to a series of treaties in an effort to expand their presence in the interior. These accords were abrogated when the fascists came to power in Italy in 1922. In the following year Mussolini’s forces embarked on the riconquista, the ruthless “reconquest” of the ancient Roman colonies of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. Drawing on his experience fighting both Italians and British under Sayyid Ahmad al-Sharif al-Sanusi, al-Mukhtar organized the armed resistance in Cyrenaica and launched an eight year campaign against Italian rule using the slogan “We will win or die!” Combining lightning raids and widespread popular support, al-Mukhtar was soon in control of what Libyans referred to as “the nocturnal government.”

Fascist forces responded with ever growing levels of brutality designed to eliminate support for the rebels. A 200-mile-long barbed wire fence was built along the Egyptian border to cut the resistance off from supporters in Egypt and Sudan. The Sanusis, already compromised by the deals they had made with the Italians, quickly folded under the pressure, leaving al-Mukhtar as the de facto leader of the anti-colonial Islamic resistance. A social transformation accompanied the desert uprising as the Murabtin (tribes of Arabized Berbers) grew more prominent through their leadership of the resistance in relation to the traditional Sa’adi Arab elite formed from the descendants of the 11th century Arab Bani Hillal conquerors of North Africa. [1] Finally, in a battle with the Italians in September 1931, al-Mukhtar was pinned beneath his fallen horse, wounded and eventually captured.

Marshal Rodolfo Graziani, the leader of the Italian military forces, came from Rome to question the resistance leader before his execution. He asked al-Mukhtar if he really believed he could win a war against the Italians, to which the unyielding al-Mukhtar replied: “War is a duty for us and victory comes from God.” [2] Al-Mukhtar was executed before an estimated 20,000 fellow Libyans and within a year Italian forces had trapped the remaining resistance leaders against the barrier with Egypt. By the time Italian rule came to an end in Libya in 1943, nearly 50% of Libya’s population had been starved, killed or forced into exile.

The little known but horrific methods used in the riconquista foreshadowed the methods of extermination practiced in the Second World War; the bombing of civilians and livestock, poisoning of wells, thousands of public hangings, the use of poison gas, prisoners thrown out of airplanes and the establishment of vast concentration camps where Libyans were sent to die of starvation and illness by the tens of thousands. Graziani felt little remorse for his tactics, but did lament “the clamor of unpopularity and slander and disparagement which was spread everywhere against me.” [3]

Though al-Mukhtar had emerged as a national hero, his memory was suppressed by the Sanusi royalty that ruled Libya from independence in 1951 to the time of their overthrow in 1969. As Qaddafi and the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC) claimed his legacy, Omar al-Mukhtar’s name and image suddenly became ubiquitous in Libya. Roads were named for him, his image appeared on Libyan currency, a center was formed for the study of the Libyan jihad and the government financed a 1981 movie, “Lion of the Desert,” in which Anthony Quinn played al-Mukhtar and Oliver Reed portrayed a menacing Marshal Graziani. While the film was shown regularly on Libyan state television, it was banned in Italy until its first broadcast on Italian TV in 2009.

A Hero to Mu’ammar Qaddafi

From the time of the 1969 military coup that brought Mu’ammar Qaddafi and the other members of the RCC to power, Libya’s “Guide” has told listeners that his childhood hero was Omar al-Mukhtar and that his father, Abu Minyar, had fought under al-Mukhtar against the Italians (though the latter claim is disputed – see Arab Times, March 4). Like al-Mukhtar, Qaddafi was also a member of a Murabtin tribe, the Qaddadfa.

Qaddafi’s efforts to identify himself with al-Mukhtar’s legacy began almost immediately. His first public speech as Libya’s new leader came on September 16, 1969 – the anniversary of al-Mukhtar’s execution – and was delivered in front of al-Mukhtar’s tomb in Benghazi. In the address, Qaddafi emphasized the need to continue the struggle for “national liberation.” However, Qaddafi’s focus on pan-Arab unity led only three months later to the first coup attempt against his regime by factions more interested in a focus on democracy and development.

Mu’ammar Qaddafi Wore a Photo of Omar al-Mukhtar During a State Visit to Italy

Mu’ammar Qaddafi Wore a Photo of Omar al-Mukhtar During a State Visit to Italy

Nevertheless, Qaddafi has continued to call on al-Mukhtar’s legacy to validate his regime, frequently referring to Libyans as “followers” of Omar al-Mukhtar, reinforcing a shared heritage of anti-colonialism designed to support Qaddafi’s own anti-Western policies. [4] In recent speeches, such as the bizarre address of February 21, Qaddafi has continued to represent himself as the heir of Omar al-Mukhtar. On February 25, Qaddafi told followers in Tripoli’s Green Square: “You are the enthusiastic youth of the [Green] revolution. You see pride and dignity in the revolution. You see history and glory in revolution – it is the jihad of the heroes. It is the revolution that gave birth to Omar al-Mukhtar” (al-Jazeera, February 25).

Despite Qaddafi’s occasional efforts to channel the spirit of Omar al-Mukhtar for his own benefit, he would most probably have been opposed by the former Qu’ranic teacher al-Mukhtar when he described his own view of jihad to a 1980 gathering:

To be engaged in the battle of jihad today is better than the worship of a thousand years of egotistical litanies of praise and penitent devotion. Islam is the religion of power, of challenge, of steadfastness and of jihad. It behooves us, therefore, to scatter our prayer beads if they were to keep our hands away from arms. We should put our copies of the Qu’ran on the shelf if they were to distract us from implementing its teachings. [5]

Libyan rebels have actively challenged Qaddafi’s claims to be the inheritor of al-Mukhtar’s legacy, particularly in eastern Libya, the Cyrenaican homeland of al-Mukhtar and his Islamic resistance. Rebel fighters in Benghazi were recently observed marching through the streets shouting the slogan used by al-Mukhtar’s forces, “We will win or die!” (BBC, March 4).

The Islamists Call on Omar al-Mukhtar

Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) was quick to make its own use of Omar al-Mukhtar’s legacy, releasing a statement entitled “In Defense and Support of the Revolution of Our Fellow Free Muslims, the Progeny of Omar al-Mukhtar” (al-Andalus Media Foundation, February 23).

The message praises the “honorable revolt against the taghut [an unjust ruler who relies on laws other than those revealed by Allah] of Libya, the modern Musaylimah [i.e. a false prophet], who has made the progeny of Omar al-Mukhtar taste 40 years of suppression, crime and humiliation… The continual massacres which the modern Musaylimah is committing through the use of African mercenaries and fighter jets against the Libyan people clearly exposes that these ruling tawagheet [pl. of taghut] are more than ready to kill Muslims and eradicate them to preserve their thrones.” The comparison with Musaylimah, a rival prophet to Muhammad who was killed by the forces of Caliph Abu Bakr at the Battle of Yamama (632 CE), is based on the 1975 release of Qaddafi’s al-Kitab al-Ahdar (Green Book), which was widely perceived in Islamic circles as a presumptuous rival to the holy Qu’ran.

Amidst much invective directed towards Qaddafi, whose brutal methods destroyed Libya’s own radical Islamist movement, AQIM declares it is with the rebels and will not desert them; “We will spend whatever we have to help you.” Though there are as of yet no indications that AQIM has fulfilled these pledges or intends to honor them in any way, the movement describes the revolt in Libya as a “jihad” and encourages the rebels to use the motto of “the Shaykh of the Mujahideen, Omar al-Mukhtar: ‘We will never surrender! We will either gain victory or die!’”

Fresh from a triumphant return to his native Egypt in the wake of the Lotus Revolution, influential Qatar-based Muslim Brother and TV Preacher Yusuf al-Qaradawi issued a fatwa (religious ruling) permitting Libyans to “put a bullet in Qaddafi’s head” and called on “the grandsons of Omar al-Mukhtar” to continue fighting until Libya was returned to its Arab and Islamic roots (al-Jazeera, February 21; al-Masry al-Youm, February 22).

However, the London-based Egyptian Salafist and al-Qaeda supporter, Dr. Hani al-Siba’i, accused al-Qaradawi in his Friday sermon of having been a friend of Gaddafi until recently, describing the rebels as the descendants of Omar al-Mukhtar, “whom we consider a martyr at the hands of the Italian criminals” (al-Ansar1.info, February 25).

A member of Qaradawi’s Islam Online editorial team elaborated on the rebels’ connection to Omar al-Mukhtar, describing them as the “descendants of the freedom fighter Omar al-Mukhtar… famous for his saying, “I believe in my right to freedom, and my country’s right to life, and this belief is stronger than any weapon.” The writer made a subtle tie between Qaddafi and the Italian imperialists who hung al-Mukhtar and thousands of others, pointing to Qaddafi’s use of a public gallows, from which “the bodies of the opposition to his ‘revolution’ hung from the nooses” (Islam Online, February 23).

Conclusion

The record of Italian rule in Libya is the basis of today’s rejection of foreign military intervention on the ground by both the loyalist and rebel camps. After leading the first Friday prayers since dislodging the regime in Benghazi, a local imam supporting the rebels warned: “We do not want any foreign military intervention. If they try to intervene, Omar Mukhtar will come forth again” (AFP, February 24).

Perhaps the last word in the debate over Omar al-Mukhtar’s legacy should go to his 90-year-old son, Muhammad Omar, who has taken a position in favor of democracy and in opposition to the visions of both al-Qaeda and al-Qaddafi, saying his father “would have a similar position to mine for the benefit of the country.” Asked what advice he would offer the embattled leader, Muhammad Omar replied: “He doesn’t listen to advice. A lot of people try to advise him but he still has a hard head and he doesn’t want to listen.” Al-Mukhtar’s son described Qaddafi’s killing of civilians as “appalling… nobody expected him to behave like this” (Irish Times, March 2; al-Arabiya, February 27).

Notes:

1. Ali Abdullatif Ahmida, The Making of Modern Libya: State Formation, Colonization, and Resistance, 2nd ed., New York, 2009.

2. Tahir al-Zawi: ‘Umar al-Mukhtar, Tripoli, 1970, p.84.

3. David Blundy and Andrew Lycett, Qaddafi and the Libyan Revolution, London, 1987, p.37.

4. Dirk Vandewalle, Libya Since Independence, London, 1998, p.130.

5. Quoted in Mahmoud Ayoub, Islam and the Third Universal Theory: The Religious Thought of Mu’ammar al-Qadhafi, London, 1987, pp. 133-34.