Andrew McGregor

November 4, 2019 (Part One of this article was published on October 29, 2019)

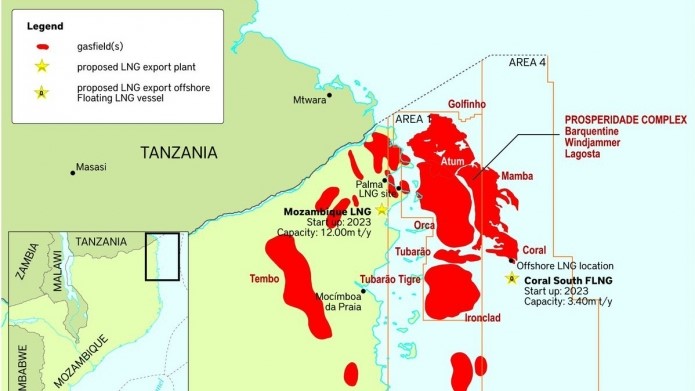

At the heart of Mozambique’s reinvigorated relationship with Moscow (see EDM, October 29) is a financial scandal that almost ruined the country. Specifically, corrupt elements in the southeast African state’s Frente de Libertação de Moçambique (FRELIMO) government and the Serviço de Informaçao e Segurança do Estado (SISE, Mozambique’s intelligence agency) secretly arranged for $2 billion in loans from foreign commercial banks for three state-owned firms without parliamentary approval in 2013–2014. Guaranteed by the government, loans from Russia’s VTB Bank and Credit Suisse were made to EMATUM, Proindicus and Mozambique Asset Management (MAM). The scandal severely undermined Mozambique’s currency and GDP growth as well as resulted in the imposition of strict new conditions on further International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank assistance. It also discouraged further foreign investment even as Maputo struggled to find up to $2 billion to finance its share of development of LNG reserves off Cabo Delgado (Macauhub.com.mo, October 18). Moscow’s VTB Bank is demanding repayment of its loan (over $500 million) by the end of the year (Clubofmozambique.com, September 9).

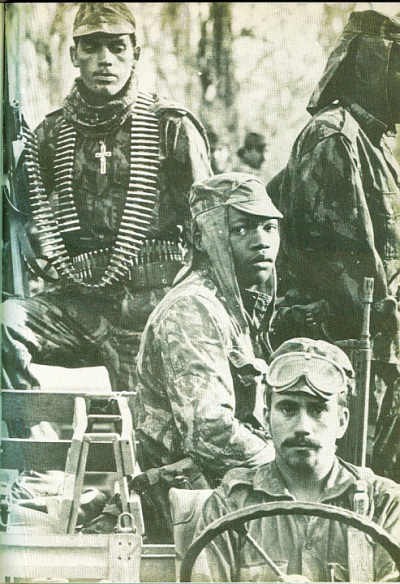

Mozambican Troops Inspect Terrorist Damage in Cabo Delgado (PetroleumEconomist)

Mozambican Troops Inspect Terrorist Damage in Cabo Delgado (PetroleumEconomist)

As Mozambique’s state security forces—the Forças de Defesa e Segurança (FDS)—proved incapable of dealing with the lightly-armed terrorists in the north, Maputo began a search for military alternatives. Initially, Erik Prince’s Dubai-based Lancaster Six Group (L6G) private security firm was in competition with Russia’s Wagner private military company (PMC) and Eeben Barlow’s South African Specialized Tasks, Training, Equipment and Protection International (STTEP) for security contracts in Cabo Delgado, with Prince promising to eliminate the terrorists in three months in return for a share of oil and natural gas revenues (Issafrica.org, November 20, 2018; Macauhub.com.mo, October 18, 2019). Prince also indicated he was interested in forming partnerships or making investments in the three state-owned firms involved in the hidden loan scandal in deals expected to lead to maritime security operations in the gas-rich Rovuma Basin (Deutsche Welle—Português Para África, June 4, 2019).

On August 20, Russia forgave 95 percent of Mozambique’s debt to the Russian Federation during a Russian-Mozambican business forum. Though the forum encouraged continuing growth in bilateral trade, some Mozambican businessmen expressed concern over the consequences of dealing with Russia while it remains under Western sanctions for its annexation of Crimea (Agência de Informação de Moçambique, August 22). Mozambican President Filipe Nyusi also encouraged Russia’s Gazprombank (specializing in financing oil and gas projects) to help invest in liquid natural gas (LNG) projects in the Rovuma Basin (Agência de Informação de Moçambique, August 22). Rosneft, a publicly-owned Russian energy firm, has three licensed exploration blocks in Mozambique and is seeking more.

Russian Cargo Plane Unloads Military Supplies at Nacala International Airport, September 26, 2019 (ClubofMozambique)

Russian Cargo Plane Unloads Military Supplies at Nacala International Airport, September 26, 2019 (ClubofMozambique)

Prince and Barlow lost out in the security competition; in late September 2019, reports emerged of armed Russians, possibly from Wagner PMC, arriving in the northern cities of Nacala and Nampula (both in Nampula province, immediately south of Cabo Delgado), allegedly accompanied by drones and helicopters (see EDM, October 15). The reports followed an admission by Mozambique’s Minister of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation that Russia was providing military equipment for use in Cabo Delgado (Noticias ao Minuto, October 5). Another report suggested the men were Russian regulars, 160 in number, who intended to create a mobile military intelligence (GRU) base and a permanent Russian naval base (Observador, September 28). The Russian embassy in Maputo has denied the presence of Russian military personnel in Mozambique (Sapo 24, October 3).

Russia’s ambassador to South Africa, Ilya Rogachev, recently defended the use of Russian PMCs in Africa, claiming critics see Russia “through colonial eyes,” overlooking Moscow’s perception of African states as “equal and not junior partners.” Rogachev added that “private military companies are not necessarily bad… I think it depends on the goals that are assigned to these companies” (Daily Maverick, October 17).

LNG Fields in Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin (BankTrack)

LNG Fields in Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin (BankTrack)

Though Cabo Delgado is deeply impoverished, organized crime runs lucrative operations there, trafficking in heroin, timber, wildlife and rubies (Globalinitiative.net, October 2018; Enact Africa, July 2, 2018). For now it remains unclear whether the terrorist attacks in the region are more closely connected to radical Islamists from the north or organized crime using Islamism as a cover. The intention could be to create enough insecurity to delay the development of a legitimate industry that could threaten their operations. It has been suggested elsewhere that the insurgency is designed to facilitate the entry of private military firms into the region and enable their exploitation of local energy resources (Deutsche Welle—Português Para África, June 13, 2018). Local journalists attempting to investigate the violence have faced intimidation, detention and even torture from government security forces (Mg.co.za, April 25).

Moscow and Maputo signed an agreement simplifying the entry of Russian naval ships into Mozambican ports and a memorandum on naval military cooperation, on April 4, 2019. Mozambique’s defense minister, Athanasio Salvador Mtumuke, noted that “our national flag depicts the Kalashnikov rifle, which symbolizes the deep relations between our countries in the military area…” (Sputnik Brasil, April 5, 2018).

Alexander Surikov, Moscow’s ambassador to Mozambique, has emphasized the readiness of Russian energy firms to develop natural gas reserves in Mozambique’s north, adding, “We provide [military] assistance to them without threatening their neighbors and rattling the saber, we only do what our partners in Mozambique ask for” (TASS, October 25).

Moscow undoubtedly has eyes on the port of Nacala, southern Africa’s deepest harbor, which lies roughly 200 miles south of the Rovuma Basin. The Mozambican town of Palma, close to the border with Tanzania, is slated for development as the main port for the Rovuma LNG industry, but it is unlikely to serve a dual purpose as a Russian naval base. Palma has suffered from attacks by the insurgents. Additionally, local demonstrations calling for a halt to LNG-related development until security is established have been dispersed by police gunfire (Agência de Informação de Moçambique, January 14). Mozambique’s most powerful neighbor, South Africa, will hold joint naval exercises for the first time with the navies of Russia and China in November.

Besides military support, the FRELIMO government is seeking strong allies as it battles internal dissatisfaction with electoral fraud, growing crime, emerging terrorism, internal political challenges and rampant corruption. While Russia may offer itself as a solution to some of these problems, the question is whether Maputo can overcome its traditional reticence to engage wholeheartedly with Moscow’s regional ambitions. Financial pressure and the lure of energy riches may be just enough to permit Russia to establish its long sought naval base in Mozambique.

This article was first published in the November 4, 2019 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Eurasia Daily Monitor.