AIS Special Report

June 13, 2025

Andrew McGregor

The year was 1923, and Egyptian explorer Hassanein Bey was on a camel-borne search for two “lost oases” in the unknown depths of the Libyan Desert. Even the South Pole had been visited less than 12 years earlier, but this corner of the south-eastern Libyan Desert remained blank on most charts despite rumors of two mountains where water could be found in an otherwise barren, burning wasteland. Hassanein Bey and his small party of desert dwellers were 111 days out from his starting point in the Libyan port of Sollum when an amazing sight appeared:

We were having a hard time of it crossing the high steep sand-dunes when suddenly mountains rose before us like medieval castles half hidden in the mist. A few minutes later the sun was on them, turning the cold gray into warm rose and pink… I had found what I came to seek. These were the mountains of Arkenu. [1]

Though Jabal Arkenu defined remote isolation at the time, Hassanein believed that “Arkenu may conceivably prove to have strategic value at some future time.” The explorer was right; only days ago the desert round Arkenu was the scene of a battle with great implications for the future of Sudan.

The Spiral Sisters

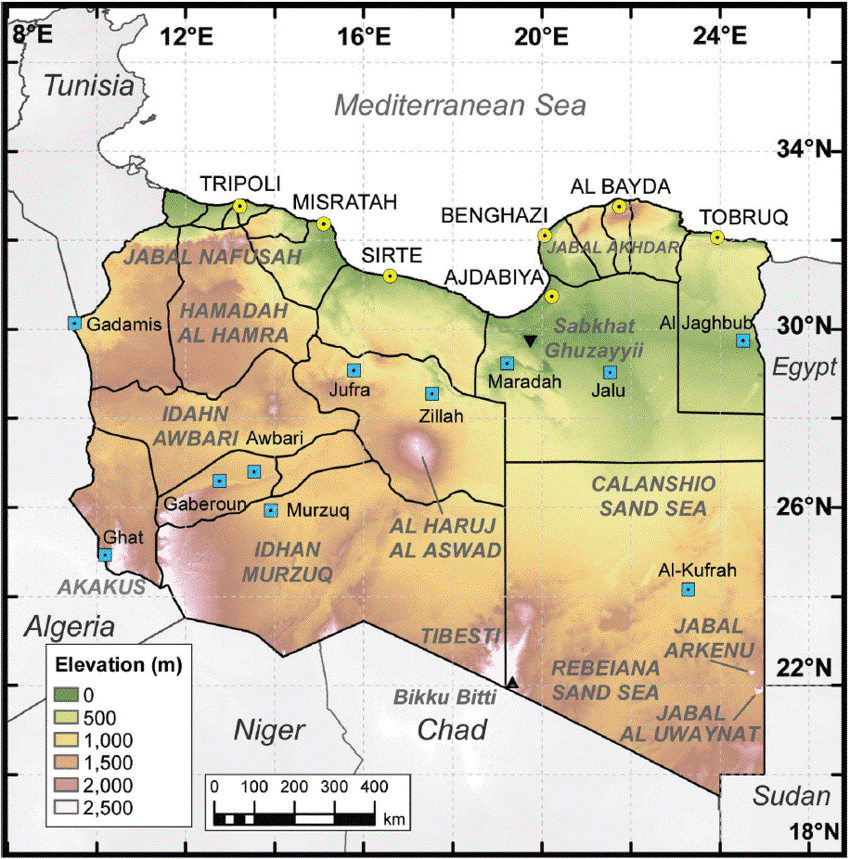

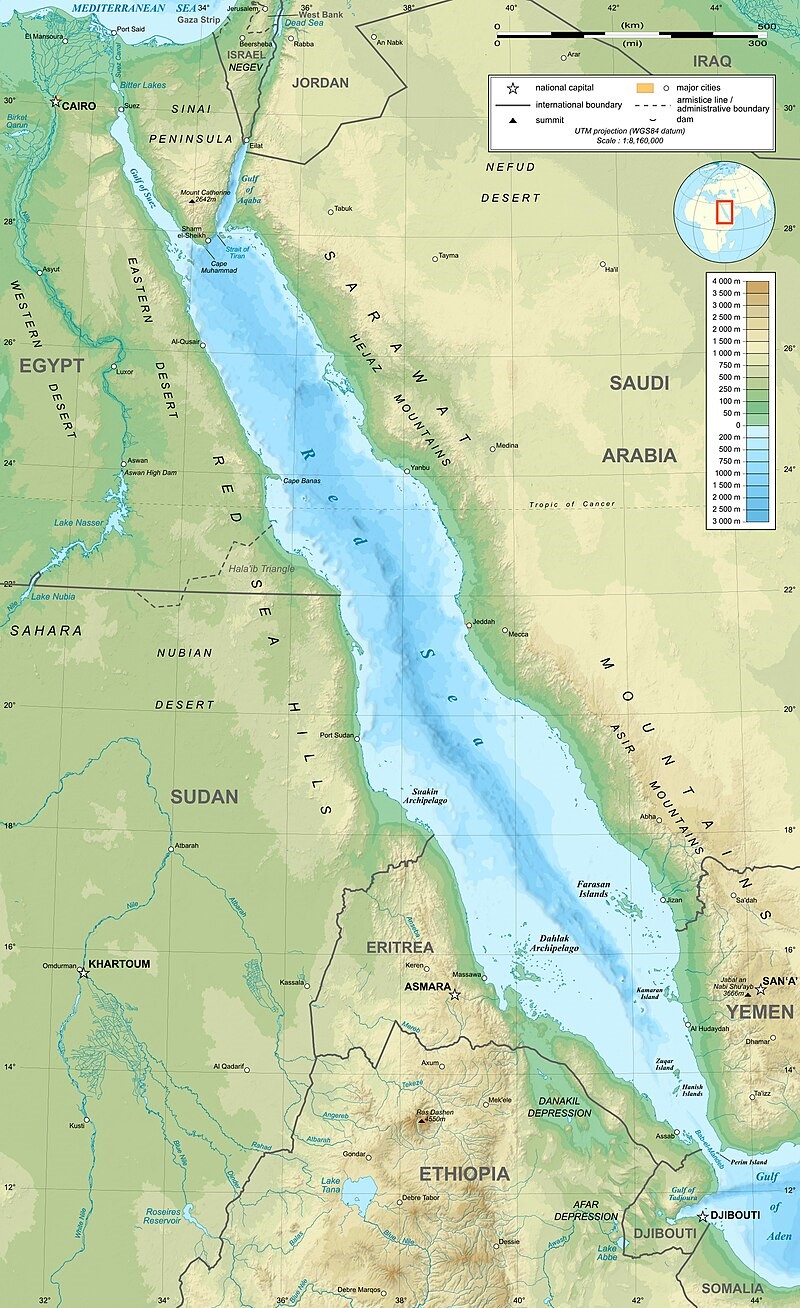

The area around Jabal Arkenu and its larger sister mountain Jabal ‘Uwaynat (25 km south-east of Jabal Arkenu) now mark the intersection of the borders of Libya, Egypt and Sudan, with the north-eastern corner of Chad not far to the south. As such, the region is now known as the Triangle area (al-Muthalath). The region around Jabal ‘Uwaynat, once a path for the Ancient Egyptians into the African interior according to recently discovered inscriptions, has now become a pathway for smugglers, mercenaries, rebels, human traffickers and gold miners. [2] In an otherwise waterless region, the massive spiral mountains collect local rainfall in natural basins within the rocks, a fact long known to the indigenous Tubu desert dwellers who brought their camels there to graze and water.

The recent discovery of gold in the region has attracted artisanal gold miners who operate in the region with little regard to borders. Egypt and Libya are seeking to replace these miners with modern mining operations, while Sudan is satisfied to collect fees through the Sudanese Minerals Resources Company without providing any services (Radio Dabanga, November 8, 2024).

The Attack on the Triangle

One hundred and two years after Hassanein Bey rediscovered the lost mountain oases, war has arrived in al-Muthalath. Possession of the desert crossing that passes through the Triangle region has suddenly become a strategic imperative for Sudanese government forces (the Sudan Armed Forces – SAF) and their adversaries in Sudan’s civil war, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) led by Muhammad Hamdan Daglo “Hemetti.” The latter group, once a government paramilitary before breaking with the SAF, has acquired the support of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and an Islamist militia belonging to the so-called Libyan National Army of “Field Marshal” Khalifa Haftar.

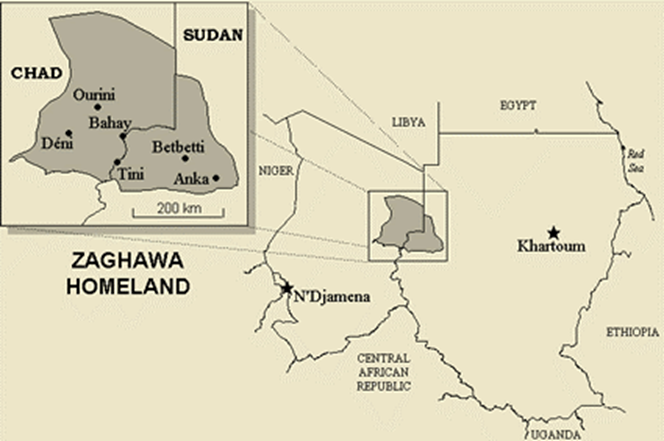

This militia, known as Subul al-Salam (“Ways of Peace”), crossed 3 km into Sudan near Jabal Arkenu on June 6 in support of RSF units (Sudan Tribune, June 11). The joint Libyan-RSF movement displaced the main Sudanese units controlling the border, the Central Reserve Forces (a police paramilitary) and the Darfur Joint Force (Atalyar, March 21; Sudan Tribune, March 22). The SAF presence consisted of only a small number of intelligence and security agents (Mada Masr, June 14). The Darfur Joint Force (a.k.a. Sudanese Joint Force, or Juba Peace Agreement Joint Forces) consists of rebel forces that were signatories to the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement and have since sided with the Port Sudan-based Sudan government. The main elements hail from Darfur’s powerful Zaghawa minority – the Sudan Liberation Movement – Minni Minawi (SLM-MM) and Jibril Ibrahim’s Justice and Equality Movement (JEM). Some SLA fighters may be using Emirati-supplied weapons obtained when they were fighting as mercenaries on behalf of Khalifa Haftar before the signing of the Juba peace agreement (France24.com, April 20).

Fighting began on June 8. The RSF announced its takeover of the Triangle border region on June 11, claiming heavy SAF losses (AFP, June 11). After a “defensive withdrawal” of government forces, the closest Sudanese army presence may now be 400 km from the Triangle region (Sudan Tribune, June 11). According to the RSF, the region contains “rich natural resources, including oil, gas and minerals (Rapidsupportforce.com, June 12).

The SAF said its forces in the Triangle region were subject to a “surprise attack” by the RSF’s “terrorist militia” and Libya’s Subul al-Salam battalion (Libya Observer, June 11). Sudan’s military further declared the role of the Libyan militia was “a reprehensible and unprecedented gesture and a flagrant violation of international law… the direct intervention of Khalifa Haftar’s forces alongside the Rapid Support Forces in the war is a blatant aggression against Sudan, its land, and its people, and an extension of the international and regional conspiracy against our country…” (Darfur 24, June 10).

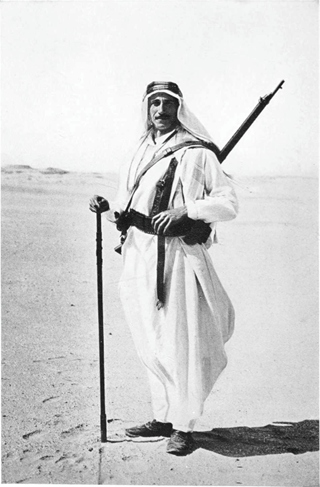

‘Abd al-Rahman Hasham al-Kilani

‘Abd al-Rahman Hasham al-Kilani

For his part, Subul al-Salam commander ‘Abd al-Rahman Hasham al-Kilani brushed over the encounter, claiming it was the result of a “misunderstanding” with the Darfur Joint Force, which believed the Libyan militia had crossed the border (Mada Masr, June 14). Haftar’s military command described allegations of participation by his forces as false and “a blatant attempt to export Sudan’s internal crisis” (Radio Dabanga, June 12).

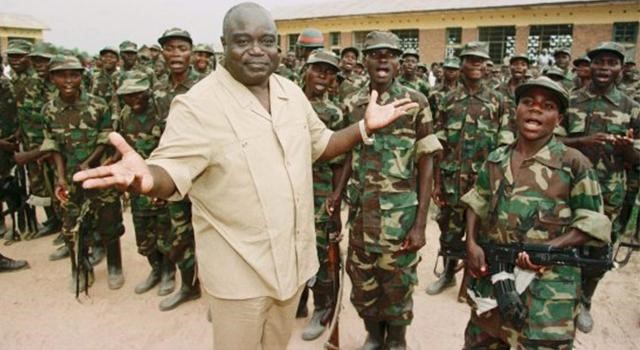

Colombian mercenaries after their convoy was attacked in North Sudan, November 20, 2024 (La Silla Vacía)

Colombian mercenaries after their convoy was attacked in North Sudan, November 20, 2024 (La Silla Vacía)

Late last year, a battalion of at least 350 Colombian mercenaries began moving in stages from Abu Dhabi to Benghazi, through the desert to the Kufra district and then south across the border into northern Darfur using a crossing just south of the Triangle region. The mercenaries, combat-experienced veterans of the Colombian army, were recruited by Dubai-based Colonel Álvaro Quijano on the understanding they would be deployed as static defense for oil installations in the Middle East. Instead their passports were seized by Libyan soldiers in Benghazi who explained they were being sent south to fight alongside the RSF in Sudan. Quijano, a Colombian, is an associate of a private security firm, the UAE-based Global Security Service Group. One convoy was ambushed by the Darfur Joint Force after crossing the border into Sudan, leading to the loss of three men. Once in Darfur, some of the Colombians have been sent into street-to-street fighting in the besieged North Darfur capital, al-Fashir, while others have been sent to train RSF fighters in Nyala, capital of South Darfur (La Silla Vacia [Bogota], November 26, 2024; March 2, 2025; March 3, 2025).

The Salafists of Kufra

The oasis of Kufra in south-eastern Libya, home of the Subul al-Salam brigade, was for centuries a major stage for trans-Saharan caravans and the shipment of slaves until its conquest by Italy in the 1930s. Kufra was dominated for centuries by indigenous Black semi-nomadic Tubu tribesmen until they were displaced by Zuwaya Arabs in 1840. Since the 2011 Libyan Revolution, Kufra has become an important stage for the transportation of sub-Saharan African migrants moving through the Triangle region to the Mediterranean coast, with numerous clashes occurring between the rival Zuwaya and Tubu communities (Libya Observer, March 5, 2018).

The brigade was formed by ‘Abd al-Rahman Hashim al-Kilani, a Madkhali Salafist, after Zuwaya clashes with the Tubu and their Darfuri allies in 2015. Salafism is a revivalist interpretation of Islam that believes Islam’s authentic form was found in the time of the Prophet Muhammad and his first three successors (the Salaf). With the encouragement and funding of Saudi Arabia, Salafism has grown rapidly in recent decades, often displacing traditional and more flexible forms of Islam around the world. It has become associated in its most extreme form with political and religious violence (Salafi-Jihadism). Madkhalism is a form of Salafism developed by Saudi shaykh Rabi’ bin Hadi al-Madkhali that emphasizes a “quietist” approach to religion, avoiding overt political involvement while emphasizing obedience to authoritarian leaders. Madkhalism has found fertile ground in Libya, where its followers have formed powerful militias in Kufra, Tripoli and other regions. [3]

Salafists oppose Sufi approaches to Islam, rejecting their rites and rituals as bid’ah (religious innovation, i.e. practices that did not exist in the times of the Salaf). Libya has a strong Sufi tradition, with the powerful Sanusi order leading the resistance to Italian colonialism. Though Kufra was the traditional headquarters of the Sanusi Sufi order, the anti-Sufi Madkhalists destroyed the funerary shrine of Sanusi leader Sayyid Muhammad al-Mahdi al-Sanusi (1844-1902) and stole his remains in 2018 (Terrorism Monitor, April 6, 2018). Since then, the Madkhalist Salafis have held the upper hand in southeastern Libya.

After its formation, Subul al-Salam quickly aligned with the forces of General Khalifa al-Haftar (a leading military commander under Mu’ammar Qaddafi until his defeat by Chadian forces in the 1987 “Toyota War” and later an alleged anti-Qaddafi CIA asset after his exile to the United States), who supplied the Zuwaya fighters with 40 armored Toyota trucks (Libya Herald, October 20, 2016).

Libya is currently divided politically between two factions – the Tobruk-based Libyan House of Representatives (HoR) dominated by al-Haftar’s Libyan National Army (LNA – an alignment of various militias and other armed groups under al-Haftar’s command rather than a true “national army”) versus the internationally recognized Government of National Unity (GNU) based in Tripoli. The latter controls western Libya (Tripolitania), while al-Haftar’s LNA controls the east (Cyrenaïca) and the south-west (Fezzan).

Tribal ties remain important in Libya; it is worth noting al-Haftar’s mother was from the Zuwaya, who have established a trading network from Kufra in the south to the Mediterranean coast in the north. Al-Haftar relies for weapons and other support from Russia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which is also believed to supply weapons to the RSF. Prior to the Libyan offensive, satellite imagery revealed an increase in UAE cargo aircraft arriving at the Kufra airport, including three IL-76TD cargo planes present between May 21 and May 31 (X, June 10). After the Libyan/RSF takeover of the Triangle region, the Sudanese Foreign Ministry denounced the “dangerous escalation of the Abu Dhabi regime-sponsored external aggression against Sudan,” describing it as a “flagrant violation of international law” (Al-Monitor, June 11; Fes News, June 11). The ministry further condemned the “blatant aggression… supported by the United Arab Emirates and its militias in the region” (Radio Dabanga, June 12). Al-Haftar also has Egyptian backing and has been supported in the field by Russian military contractors, most notably in his failed 2019 campaign to take Tripoli and unite Libya under his rule.

The Subul al-Salam brigade has clashed with Sudanese fighters before, killing 13 members of the Darfuri Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) in 2016. The members of JEM, a mainly Zaghawa rebel group, were operating as mercenaries near the oasis of Jaghbub at the time alongside a group of indigenous Black Tubu fighters.

Saddam al-Hafter – The Heir Apparent

Subul al-Salam comes under the direction of Khalifa Haftar’s son, Saddam, who is being groomed to succeed his 81-year-old father. At the same time the Russian-backed Khalifa is being supplied with heavy weapons, armored vehicles and Pantsir air defense systems by the Kremlin, Saddam has been holding quiet meetings in Washington with top state department and intelligence officials in the Trump administration (Militarnyi.com, May 26; MEE, June 12). Saddam is overseeing the Russian rehabilitation of a disused Qaddafi-era airbase (Matan al-Sarra) in southeastern Libya for use by Russia’s Africa Corps (EDM, April 17). Al-Haftar has already been accused of using Matan al-Sarra as a distribution point for arms headed to the RSF. (Sudan Tribune, June 11). When completed, Matan al-Sarra will join six other bases used by Russian forces in Haftar-controlled regions of Libya – al-Khadim, al-Jufra, Brak al-Shati, al-Wigh, Tamanhint, and al-Qardabiya

RSF Strategic Objectives

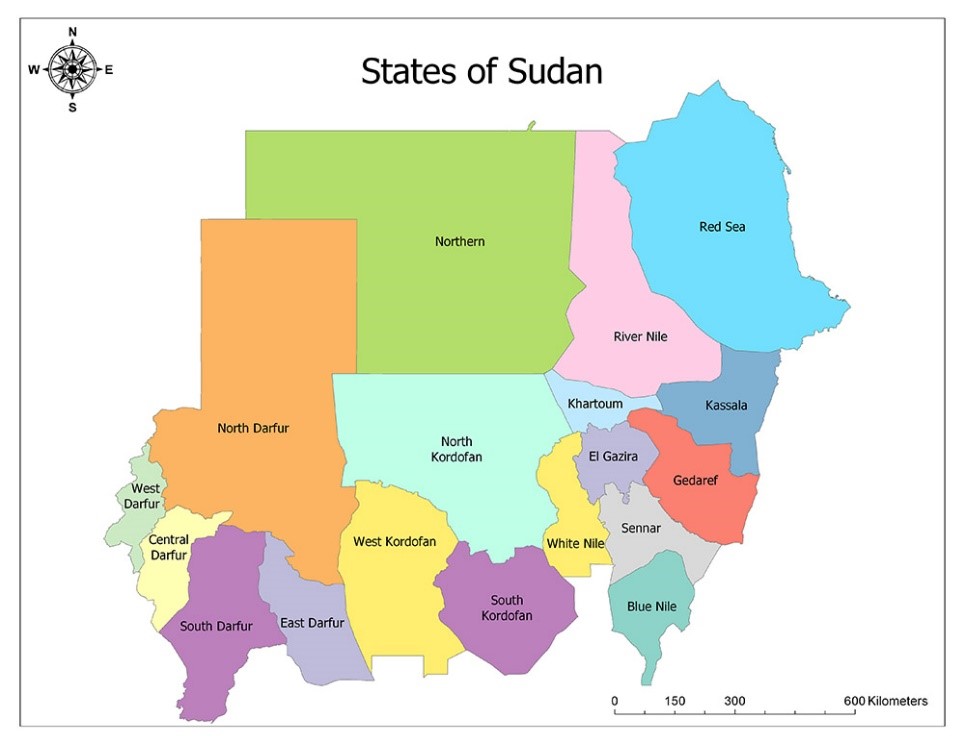

The RSF is looking to take the war into the Northern Province (home of the Arab-Nubian elites that have governed Sudan since independence), and notes that control of the Triangle region “is a significant step that will impact multiple combat front lines, particularly in the northern desert” (Rapidsupportforce.com, June 12). The RSF is dominated by Sudan’s western Arabs (residents of Kordofan and Darfur) who have been rivals of the more politically and economically successful northern Arabs since the days of the Mahdiyya (1881-1899).

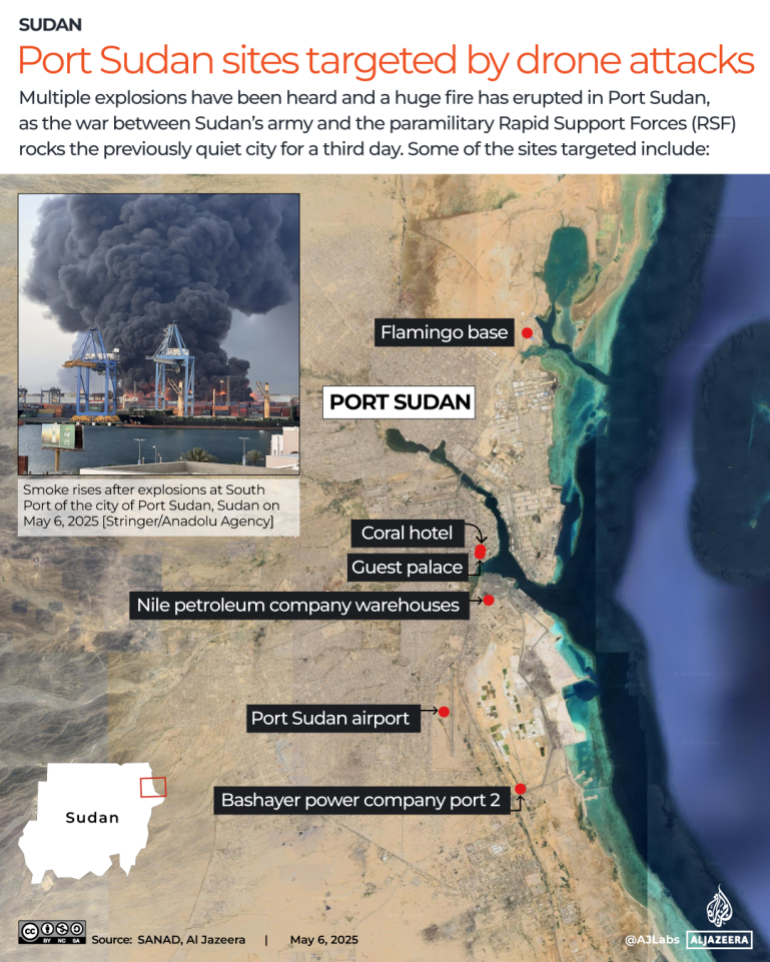

As a step towards consolidating control of northern Sudan and supply lines from southern Libya, the RSF took al-Malha (a Meidobi town 210 km northeast of al-Fashir) in March, killing 40 people and burning down the market after looting it. Al-Malha connects northeast to the strategic Nile town of al-Dabba in Northern State via the Wadi al-Milk and east to the town of Hamrat al-Shaykh in North Kordofan, which the RSF hopes to incorporate into a new state together with Darfur, one independent of the Transitional Sovereignty Council (TSC) government and the SAF in the temporary Sudanese capital in Port Sudan.

The RSF is increasingly concerned that it may lose its most important supply line for UAE arms and military materiel, which runs from an Emirati-built airbase in Um Jaras (or Amjarass, Ennedi province) east into West Darfur. SAF commander and TSC chairman General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan has demanded that Chad dismantle the Um Jaras base and close Chad’s border with Darfur to RSF-destined logistical convoys. Chad’s ruler, Mahamat Idris Déby Itno, like many of Chad’s ruling elite, is a member of the Zaghawa ethnic group, which straddles the Chad-Sudan border. However, the Darfur Zaghawa oppose the Arab-dominated RSF and sent a delegation of elders in February to meet with President Déby to urge an end to Chadian accommodation of the RSF (Mada Masr, March 7). Should Chad’s leadership decide to back away from the RSF, the establishment of a secure alternative supply route for UAE arms and supplies through Libya to northern Sudan will become imperative.

The RSF is increasingly concerned that it may lose its most important supply line for UAE arms and military materiel, which runs from an Emirati-built airbase in Um Jaras (or Amjarass, Ennedi province) east into West Darfur. SAF commander and TSC chairman General ‘Abd al-Fatah al-Burhan has demanded that Chad dismantle the Um Jaras base and close Chad’s border with Darfur to RSF-destined logistical convoys. Chad’s ruler, Mahamat Idris Déby Itno, like many of Chad’s ruling elite, is a member of the Zaghawa ethnic group, which straddles the Chad-Sudan border. However, the Darfur Zaghawa oppose the Arab-dominated RSF and sent a delegation of elders in February to meet with President Déby to urge an end to Chadian accommodation of the RSF (Mada Masr, March 7). Should Chad’s leadership decide to back away from the RSF, the establishment of a secure alternative supply route for UAE arms and supplies through Libya to northern Sudan will become imperative.

Notes

- AM Hassanein Bey: The Lost Oases, New York and London, 1925, pp. 210-217.

- Andrew McGregor, “Egyptian exploration of the African interior – Caravans to Yam,” Ancient History Magazine 15, April/May 2017, pp. 38-45. For Jabal ‘Uwaynat, see: “Jabal ‘Uwaynat: Mysterious Desert Mountain Becomes a Three-Border Security Flashpoint,” AIS Special Report, June 13, 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=3930

- Andrew McGregor, “Radical Loyalty and the Libyan Crisis: A Profile of Salafist Shaykh Rabi’ bin Hadi al-Madkhali,” Jamestown Foundation, January 2017, https://www.aberfoylesecurity.com/?p=5244