Andrew McGregor

January 29, 2013

Alghabass ag Intallah, a young Tuareg politician and tribal leader, has placed himself in a position where he can play a crucial role in determining the future of the ongoing conflict in northern Mali. Ag Intallah’s January 23 split from the Islamist Ansar al-Din of Iyad ag Ghali is a serious blow to the movement and a challenge to Ag Ghali’s leadership ambitions in the region.

Prior to his split from Ansar al-Din, Ag Intallah has been, for the last year, the perplexing public face of Ansar al-Din; a man who not long ago embodied Tuareg traditional rule and opposition to religious and political extremism but who now acted as the lead negotiator for Ansar al-Din, a radical Islamist movement allied with al-Qaeda.

Forming the Mouvement Islamique de l’Azawad

Ag Intallah’s new group, the Mouvement Islamique de l’Azawad (MIA), is almost exclusively composed of Malian Tuareg who have left the ranks of the radical Ansar al-Din as the latter is hammered by French airstrikes while falling back before a French-led ground offensive. Ag Intallah was immediately joined in the MIA by former Ansar al-Din spokesman Muhammad ag Arib. The movement’s founding statement described the defectors as “the moderate wing of Ansar al-Din” and added that the newly formed MIA “totally differentiates itself from any terrorist group, condemns and rejects any form of extremism and terrorism and commits itself to fighting them.” While appealing to Bamako and Paris to cease hostilities in the areas it claimed to control (Kidal and Menaka), the movement also expressed its interest in “the establishment of an inclusive political dialogue” (Tout sur l’Algerie, January 24). Following the announcement, Alghabass told Reuters by phone that: “We want to wage our war and not that of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb [AQIM]” (Reuters, January 24).

This approach would be consistent with the view of French Defense Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian, who recently explained that northern Mali’s “terrorist and jihadist groups must be differentiated clearly from the movements that are representing the north of Mali and the people of this area in all of their diversity. Neither these movements nor the people are targeted under any circumstances by the military action which we have started…” (RFI, January 17). Statements such as these appear to be a clear invitation for the Tuareg to abandon Ansar al-Din’s hardliners and their al-Qaeda associates to avoid being targeted by French military power.

A day before the MIA’s announcement, an Algerian government source told an Algiers daily that if the new formation agrees to fight terrorist groups (specifically AQIM and MUJWA) and respected the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Mali, “they will be qualified to speak in the name of the Ifoghas [Alghabass’ tribe] and we shall help them” (Tour sur l’Algerie, January 23).

Two days after the creation of the MIA, Ansar al-Din suffered another blow when Colonel Kamo ag Menali announced he was leaving Ansar al-Din to join the secular Tuareg nationalists of the Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad. At the time of his defection, the Colonel was based at the time in Léré, close to the Mauritanian border (Sahara Media [Nouakchott], January 25).

Background

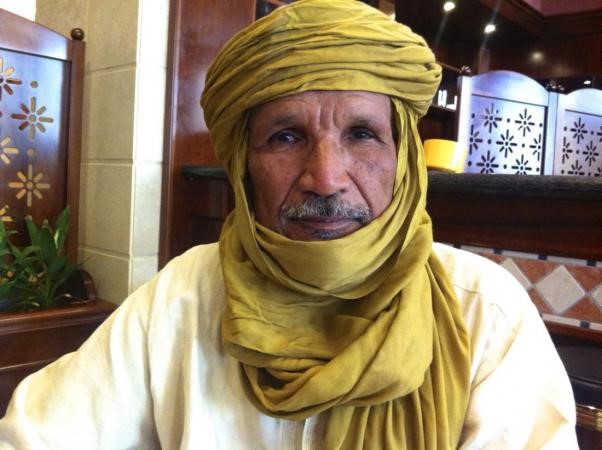

Alghabaas ag Intallah has been described as tall (about 6’4”) and imposing, with a quiet charisma that reflects his station in the local Tuareg hierarchy. [1] Alghabass was born into the highest levels of the Kidal Tuareg leadership as the middle son of the Amenokal (chief) of the noble Ifoghas tribe, the traditional rulers of the Kidal region. His father, Intallah ag Attaher, has been Amenokal since 1963, but has been ailing for some years and has lately devolved much of his power on his designated successor, Alghabass

Though blessed with many advantages in his pursuit of election to Mali’s National Assembly, Alghabass has been pursued by charges of electoral irregularities, particularly in what was expected to be a close contest with Zeid ag Hamzata in July, 2007. Ag Hamzata’s campaign registration documents mysteriously disappeared only hours before the filing deadline, a situation remarkably similar to one that occurred when Ag Hamzata had challenged Alghabass’ younger brother for the mayoralty of Kidal three years earlier. Rumors in Kidal insisted that the registrar had been paid $20,000 to “lose” Ag Hamzata’s papers. [2] One Bamako daily suggested Alghabass’ election was reliant on “the partiality of the representatives of the administration, fraud, corruption, buying of officials at polling stations and the abusive use of proxies” (Le Républicain [Bamako], August 3, 2007).

Ag Intallah is reported to have useful contacts with the Qatari royal family, for whom he arranges hunting trips in the Sahara (Jeune Afrique, October 3, 2012; Maliweb.net, November 21, 2011).

Opposing Extremism in Azawad

Alghabass’ personality and place in the Tuareg hierarchy expanded his political role from National Assembly deputy to regional mediator and spokesperson for the Tuareg of Kidal. In September, 2007, Alghabass was deeply involved in mediation with the rebel movement of Ibrahim ag Bahanga to obtain the release of a large number of hostages, a role for which his background made him well-suited (Le Républicain [Bamako], September 20, 2007; L’Indépendant, September 19, 2007).

In the early months of 2009, Alghabass came into conflict with Lieutenant Colonel Lamana Ould Bou, a military intelligence officer with Mali’s Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE) and a former member of the Front Islamique Arabe de l’Azawad (Arab Islamic Front of Azawad – FIAA), an Arab rebel movement active in northern Mali. Colonel Lamana had been active in organizing a number of Arab militias in northern Mali that had been partially credited with driving Tuareg rebel forces under the late Ibrahim ag Bahanga from the region in February, 2009 (see Terrorism Monitor, February 25, 2009). Alghabass, however, told U.S. diplomats in Bamako that Lamana’s men were nothing but Arab smugglers and bandits working out of the relatively lawless In Khalil border post with Algeria (In Khalil has lately become the base of Mokhtar Belmokhtar’s new AQIM faction – see Terrorism Monitor Brief, January 10).

Colonel Lamana was assassinated in June, 2009 in Timbuktu by assassins believed to belong to AQIM. There were later reports that Arab tribesmen from Timbuktu took revenge for the murder by killing four AQIM members in November, 2010 (AFP, November 4, 2010; see also Terrorism Monitor Brief, June 25, 2009).

In August 2009, Alghabass and fellow National Assembly deputy Ahmada ag Bibi (later a leading member of Ansar al-Din) told American diplomats in Bamako that the Malian government had failed to implement the 2006 Algiers Accords, particularly in terms of reintegrating Tuareg fighters into the Malian military, incorporating Tuareg youth into the national economy and sponsoring development projects in northern Mali. Both Alghabass and Ag Bibi urged the U.S. government to pressure Bamako to use the Tuareg against al-Qaeda elements active in northern Mali, apparently without success. [3] By late 2009, Alghabass was taking a public hardline towards the Salafist militants; “Our agenda is to form a delegation of resource persons to see where al-Qaeda is and ask it to leave our territory, or we will fight (Le Républicain [Bamako], December 9, 2009).

Alghabass also told U.S. diplomats that the outbreak of hostage-taking by AQIM groups could be blamed on the reluctance or unwillingness of Algerian and Mali to undertake effective counterterrorist operations, suggesting that al-Qaeda elements in the region could be defeated easily by any serious effort on the part of Algiers or Bamako. Alghabass added that he had tried to raise the issue of the failure of Mali’s security services to confront AQIM at the National Assembly, but had been personally dissuaded by then-President Amadou Toumani Touré. [4]

Joining Ansar al-Din

Alghabass’ February, 2012 decision to leave the MNLA for Iyad ag Ghali’s Ansar al-Din movement may have been encouraged by an incident that occurred when the rebellion was just starting in January, 2012. Alghabass’ was reported to have been safely removed from Kidal by Iyad ag Ghali just as Tuareg loyalists were searching house-to-house for Alghabass and other suspected rebel leaders (Jeune Afrique, April 20, 2012). The loyalist militia was led by Colonel al-Hajj ag Gamou, a member of the large Imghad Tuareg clan, a “vassal” clan in the Tuareg hierarchy that discovered a combination of democracy and demographics could give the Imghad political power over their customary superiors, the “noble” Ifhoghas.

The relationship between Alghabass and Iyad ag Ghali was complicated by the fact that the latter was clearly leader of the Ansar al-Din, but by any understanding of the local traditional Tuareg hierarchy, Alghabass was quite clearly senior to Iyad ag Ghali, a factor that might have encouraged Iyad in making Alghabass the movement’s senior negotiator in distant Ouagadougou. Deepening Iyad ag Ghali’s resentment was the fact that he was bypassed as the appointed successor of the Ifogha in favor of the Amenokal’s son (Jeune Afrique, November 3, 2012).

As a representative in the National Assembly, Alghabass was known as a strong supporter of President Amadou Toumani Touré. Before announcing his departure from the government to join the MNLA rebels, Alghabass is reported to have called President Touré to express his disappointment that, despite his personal loyalty to the government, Malian policy had failed to develop or benefit the north (Toumast Press, January 27).

Alghabass’ membership in Ansar al-Din conflicted with the views of his father, Intallah ag Attaher, who issued a public statement in mid-April, 2012 stating his support for the MNLA and calling for the international community to recognize the independence of Azawad (northern Mali). The Amenokal went on to ask all groups that did not support independence (including Ansar al-Din and AQIM) to leave the region and condemned “all groups who kidnap foreigners in Azawad and terrorize the local population” (Toumast Press, April 18, 2012). However, Intallah ag Attaher’s repudiation of Ansar al-Din did not prevent anti-Ansar rioters from targeting his home in June, 2012 in the absence of his son (Le Républicain [Bamako], June 6, 2012).

In March, 2012, Alghabass was telling interviewers that he was fighting for the introduction of Shari’a in northern Mali (Jeune Afrique, March 22, 2012). By June, 2012, however, there were reports from the Tuareg community that a faction of Ansar al-Din led by Alghabass was in growing conflict with Iyad ag Ghali’s hard-line Islamists (Toumast Press, June 9, 2012).

Ag Intallah led a delegation of seven Ansar al-Din representatives to the first joint talks with the MNLA on November 16, 2012. Hosted in Ouagadougu and mediated by Burkina Faso president Blaise Compaoré, the talks were viewed by some as a first step in detaching Ansar al-Din from its Islamist allies. The creation of the MIA will likely bring Alghabass and his followers into an alliance with the MNLA, which has already taken advantage of the French intervention to seize Kidal. MNLA spokesman Moussa ag Assarid was quick to express the movement’s support for the military intervention; “We’re ready to help; we are already involved in the fight against terrorism… We can do the job on the ground. We’ve got men, arms and, above all, the desire to rid Azawad [northern Mali] of terrorism” (AFP, January 14). However, the MNLA must change its separatist agenda to be welcomed into negotiations with France and Algeria.

Conclusion

The loss of Alghabass ag Intallah will have a significant impact on the degree of support Ansar al-Din leader Iyad ag Ghali can count on in his home region of Kidal. However, the departure of Ansar al-Din’s more moderate members may encourage greater extremism in the remaining faction. Ansar al-Din spokesman Sanda Ould Bouamama appeared to bringing the movement in line with the global jihad preached by al-Qaeda in his reaction to the French intervention in northern Mali: “Oil companies lead this war. Hence, it has become the duty of the mujahideen all over the world, whether Algerians or other nationalities, to target the interests of the West and its companies that finance the war” (al-Sharq al-Awsat, January 23).

Alghabass ag Intallah has an opportunity to help save Mali’s Tuareg militants from destruction by offering a refuge for disillusioned followers of Ansar al-Din. By participating in joint “counter-terrorism” operations with the MNLA (and possibly alongside advancing Franco-Malian forces) against AQIM and their Islamist allies in the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJWA), Alghabass may embody the reassertion of traditional leadership in the Tuareg communities of the Kidal regon and renew his role as a lead negotiator – this time as the representative of a primarily nationalist movement rather than as the representative of an Islamist movement with little popular support in Kidal. Bamako cannot hope to resolve the crisis in northern Mali without the cooperation of local partners – preferably known commodities with experience at negotiation and a well-grounded constituency. Ag Intallah fits the bill but knows it, and will use the leverage offered to ensure his political future while reshaping the political structure of his homeland.

Notes

1. Cable 09BAMAKO211, U.S. Embassy Bamako, April 6, 2009, http://wikileaks.org/cable/2009/04/09BAMAKO211.html

2. Cable 07BAMAKO594, U.S. Embassy Bamako, June 1, 2007, http://wikileaks.org/cable/2007/06/07BAMAKO594.html

3. Cable 09BAMAKO567, U.S. Embassy, Bamako, Agust 26, 2009, http://wikileaks.org/cable/2009/08/09BAMAKO567.html

4. Cable 09BAMAKO211, U.S. Embassy Bamako, April 6, 2009, http://wikileaks.org/cable/2009/04/09BAMAKO211.html