Andrew McGregor

November 4 2010

On October 14 former Tuareg rebels under the command of Ibrahim ag Bahanga attacked a heavily armed convoy of cocaine smugglers roughly 60 miles from the northern Mali town of Kidal. Some 12 people were killed in the clash in which the Tuareg fighters received “material support” from the Malian army, according to a local government official (Reuters, October 18; Jeune Afrique, October 18; Afrique en Ligne, October 20). It is unclear whether the Tuareg fighters were acting under their own initiative as a kind of demonstration of their potential in combating AQIM and narco-traffickers, or whether the action was officially sanctioned by the Bamako government, which has so far been reluctant to rearm the Tuareg. The traffickers were alleged to be running a shipment of cocaine from Morocco to Egypt across the sparsely populated Sahel region.

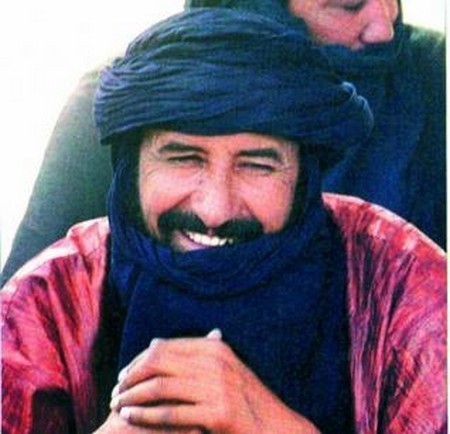

Ag Bahanga is a noted smuggler and rebel commander who is a leading proponent of transforming former Tuareg rebels into armed units tasked with expelling al-Qaeda operatives from the Sahel/Sahara region. Though his proposal was given a sympathetic ear in Algeria, the long-time rebel is little trusted in Bamako and continues to operate from self-imposed exile in Libya. Ag Bahanga’s proposal has elicited little sympathy from Mali’s press. One commentator noted that “in the recent past Bahanga has demonstrated proof of his inconsistency and his warlike inclination by swearing peace one day and indulging in atrocities the next day” (Info Matin [Bamako], October 20). Another commentator complained that Ag Bahanga’s “renewed patriotism” was “hard to understand” and rearming the Tuareg could turn Mali into “another Afghanistan” (Nouvelle Libération [Bamako], October 12).

Nevertheless, the Tuareg attack came only days after Ag Bahanga was reported to have met with Malian president Amadou Toumani Touré on the sidelines of the October 10 African-Arab summit meeting in the Libyan city of Sirte to discuss the reintegration of Ag Bahanga and his men into the Malian army (Nouvelle Libération [Bamako], October 12).

According to former rebel spokesman Ahmada Ag Bibi (now a parliamentary deputy in Bamako), “AQIM wants to dirty the image of our region. We aren’t going to accept that. [AQIM fighters] often seek shelter on our land, and we know the terrain. If we were armed we could easily take care of them… We’re just waiting for the Malian government to give us the green light to chase al-Qaeda from our desert” (AFP, October 10).

The 2006 Algiers Accord between Bamako and the Tuareg rebels provides for the establishment of Tuareg military units under officers of the Malian regular army, but like many aspects of the accord, these provisions have never been implemented. There are indications now, however, that such units may be formed soon – according to an authority in the Kidal administration, their establishment may be only weeks away (Afrique en Ligne, October 20; Ennahar [Algiers], October 10).

A small number of Tuareg are believed to be working for AQIM as drivers and guides, though there are also unconfirmed reports that a Tuareg imam from Kidal named Abdelkrim has become an amir in the AQIM organization (Libération [Bamako], October 31; Jeune Afrique, October 9). Though direct Tuareg participation in AQIM activities may be limited, there are signs, nonetheless, that the massive influx of cash into the region from AQIM-obtained ransoms has had an indirect benefit to the Tuareg and Arab tribes of the region. In the town of Kidal, expansive new villas and shiny 4 x 4’s have begun to appear in a region almost entirely devoid of development (Libération [Bamako], October 31).

A veteran Tuareg rebel, Iyad ag Ghali, has been designated as the government’s official mediator with AQIM forces in northern Mali (Le Républicain [Bamako], October 4). An AQIM katiba (military unit) led by Abd al-Hamid Abu Zaid is believed to have established bases in the rugged Timetrine Mountains of northern Mali (once a refuge for Tuareg rebels) and is currently believed to be holding French and African hostages there who were kidnapped from the French-owned uranium operations in neighboring Niger (Le Monde, October 18).

Many Malian politicians complain that they have been excluded from the decision-making process in regard to the security of northern Mali. Such decisions are now made exclusively by the president, himself a former military commander in the north, and a small group of senior officers, including General Habib Sissoko, General Kafougouna Kone, Brigadier Gabriel Poudiougou and Colonel Mamy Coulibaly (Jeune Afrique, October 9).

This article first appeared in the November 4 2010 issue of the Jamestown Foundation’s Terrorism Monitor